Chip Somodevilla

Let’s start by asking what a core holding is – or should be. Many investors simply own the S&P 500 (VOO) and leave it at that. It’s the index usually available in 401K plans and it’s hard to argue that it lacks diversification. Large cap US stocks feel pretty “core,” with small and mid cap indexes and international indexes being the first potential additions. Warren Buffett, interestingly, is a great proponent of the S&P 500 by itself, leaving instructions to the trustee of his will to put 90% of funds set aside for his wife in it. He has also used it since the early days of Berkshire Hathaway (NYSE:BRK.A)(NYSE:BRK.B) as the benchmark for Berkshire’s performance. The reality, of course, is that the bulk of Buffett’s assets continue to be in Berkshire.

Buffett’s favorable thinking about the S&P 500 is probably pretty similar to that of the decision makers who make it the top choice for 401Ks. Here are some of the likely reasons:

- It has simplicity. It contains most of what you need in a single fund or ETF. Owners don’t need to think about it much.

- It provides diversification. You own enough different companies in enough different industries that an unexpected negative event affecting a particular sector isn’t likely to ruin an investor.

- It leaves room for an informed investor to add in areas such as small and mid caps or international indexes or individual stocks.

- Because the S&P 500 is market cap weighted, the most successful stocks in the 500 index become increasingly important to the index as they grow and rise in price. You are assured of owning the winners. You won’t load up on them at the bottom, but you won’t miss the bulk of their rise. I wrote about this phenomenon and compared it to Berkshire Hathaway in this article.

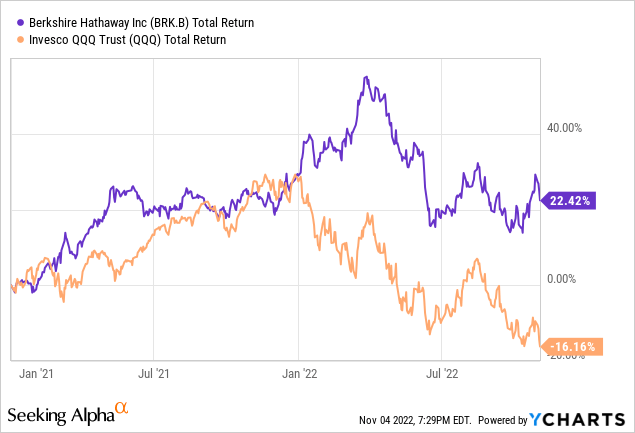

So why not just buy the S&P 500 and stop thinking about a better core holding? As I explained in the article linked above, the market cap weighting advantage of the 500 index has a flip side, which can damage investors. This is especially true following periods in which a particular sector or a handful of stocks have been so successful that they come to dominate index returns. Not long ago, a half dozen or so tech/media stocks accounted for more than 30% of the index. Over the past year, as their prices collapsed, their large percentage of the index has had a major negative impact on the S&P 500 performance. The absence of highly valued tech/media companies is probably Berkshire’s major departure from the index and the source of its recent outperformance. Here’s a chart showing how Berkshire performed in comparison to the tech-heavy Invesco QQQ ETF (QQQ) since the beginning of 2021:

How Berkshire Compares To The Index

Berkshire is highly diversified and largely domestic. It contains roughly 100 wholly owned subsidiaries, which range in size from its large collection of insurance businesses, BNSF railroad, and its Apple stock position to much smaller companies like Dairy Queen and See’s Candies. It thus has holdings at all levels of capitalization. While it doesn’t mimic the S&P 500 in sector weightings, it does diversify in a way that limits risk.

Insurance is one of the most generally stable of industries with risk mainly in idiosyncratic weather events and events like the 9/11 attacks. The Burlington Northern railroad unit reflects the economy but is less cyclical than most industrial companies. BHE is similarly stable, and like BNSF, it benefits from regulatory requirements that impose capital expenditures but assure solid returns. Apple has some economic sensitivity but has so far not suffered materially from downturns. Many small and medium-sized housing and housing-related subsidiaries are much more cyclical but have good long term growth prospects. On balance the Berkshire businesses are more stable and conservative than the S&P 500 as a whole.

Many investors are probably unaware that almost 30% of S&P 500 revenues are international. If you own the S&P index, you have a lot of exposure to Europe and quite a bit to Asia. Both business conditions and currency exchange rates have significant impact on the S&P index. Berkshire by contrast is largely domestic, with BNSF and BHE entirely so and its insurance businesses predominantly so. Buffett frequently cites progress in living standards in the US and says that he is “all in” on America. Berkshire is not vulnerable to many specific risks from other countries. Berkshire’s only stock investments of even modest size are in Japan, and they are fully hedged against currency risk. Buffett has clearly been unable to find large scale international investments which meet his standards for safe return and offer means to hedge currency swings.

Berkshire Comes With Many Advantages

I have never owned the S&P 500 or any other index. For most of my life as an investor I have owned individual stocks plus a few country CEFs. Starting in 2000 Berkshire Hathaway (BRK.A)(BRK.B) emerged as the core holding of my portfolio. It is now much larger than all other stock investments combined. There are several arguments supporting this approach. With Berkshire it starts with the fact that less is more. Berkshire obviously has a single CEO, a single designated successor, a single board, and a much smaller number of business units than the S&P 500. This provides Berkshire investors with a huge advantage.

If you own the S&P 500, you get, for one thing, 500 CEOs accompanied by 500 boards of directors. A few of them are excellent, Tim Cook of Apple (AAPL) for example, but many of the 500 CEOs follow their personal interests and destroy value for shareholders. The great CEOs like Tim Cook and Jeff Bezos create huge value but they are only two CEOs out of 500. One should bear in mind that CEOs like Tim Cook are offset by CEOs like Mark Zuckerberg and Elon Musk. The average CEO of the 500 is, well, average. It is pretty well beyond dispute that Warren Buffett and his designated successor are far better than the average S&P 500 CEO.

It shouldn’t come as a surprise that Warren Buffett and sidekick Charlie Munger have put together a better collection of companies with better management, better and happier employees, as well as more loyal customers. Berkshire also benefits from a highly informed and sophisticated shareholder base that Buffett rightly considers an asset. They have installed their own philosophy of value investing, which differs from many value investments in that it also has considerable growth. This fact is made clear by Berkshire’s inclusion in both value and growth indexes.

With roughly 100 subsidiaries and a large stock portfolio Berkshire is in one sense highly diversified. Most of the companies absorbed through acquisition are best-of-breed or among the best. BNSF is one of the two premier railroads. Berkshire Hathaway Energy is one of the largest utilities and among the most profitable. Berkshire’s insurance and reinsurance businesses have achieved outstanding combined ratios and its large stock portfolio contains dividend paying stocks, which offset future claims. Its large Apple position has outperformed most mega-cap market leaders both recently and over the long term.

It is in part the synergy of the various parts of Berkshire ,which makes it hard to analyze. Should the stock portfolio be treated as a freestanding entity or a subordinate element of the insurance business? Where does insurance float belong? Should float be subtracted as a liability or understood as a more or less permanent asset, which is likely to perpetually roll over? Should we evaluate Berkshire’s publicly-owned stocks using Buffett’s approach of “looking through” to the underlying assets, earnings, and cash flow? How do we deal with the fact that some Berkshire units are best valued by metrics like P/E ratio, some reprice daily in the market, and some are best compared to similar companies?

Events in the last five years have made it difficult to produce reliable measures of Berkshire’s performance. Accounting Standards Update (ASU) ASU 2016-1 made nominal income and balance sheet numbers wildly irregular and unhelpful because of the requirement to report earnings with updates of stock portfolio market value starting in 2017. The pandemic lockdown/recession followed by high inflation further scrambled what could potentially have been figured out by backing reported portfolio changes out of reported earnings.

At the time the rule went into effect, Berkshire’s return on equity, which along with book value (which also now requires regular correction), was around 9%. That included the fact that cash reserves, at the time yielding near zero, were dragging down ROE by as much as 20%. Higher interest rates should reduce the drag considerably as would successful investments. A consolidation of Occidental Petroleum (OXY) operating numbers with Berkshire’s results should also help. Buybacks do much more because they reduce the equity denominator. ROE in a “normal” year might be around 10-11%, not bad for a company not generally thought of a “growth” company.

Perhaps the biggest operational advantage of Berkshire is its unique structure in which the operations of subsidiaries are highly decentralized while cash flow not needed in particular subsidiaries is returned to corporate headquarters. The CEO, who is also chief investment officer, then allocates capital to whatever internal or external opportunities are available. No other company that I know of is organized in quite this way, which encourages responsibility and creativity of managers at every level while having centralized capital allocation.

Addition By Subtraction

Berkshire owns very little tech and very little in the way of small growing companies in their infancy. It never has. The one tech company it owns in size is Apple, which might be better described as a consumer company with a powerful brand supported by tech. Its record with very young high concept companies is spotty, with a success of sorts in Snowflake (SNOW) and less success in fintech startups in India and Brazil. The question for investors is whether not owning start-up tech is a bad thing.

Most of Berkshire’s outstanding long-term positions have been in well established companies, which still had plenty of future growth in them. One such company was GEICO, which had fallen on hard times after its early growth stage founded on insuring government employees by seeking growth recklessly and drastically under-reserving. Buffett bought near the bottom and enjoyed a 30% annual compounded return from 1976 until Berkshire bought the 49% of the company it didn’t already own in 1999. Coca-Cola (KO) was almost 100 years old when Buffett bought it on a major scale and rode its last major period of growth. Berkshire enjoyed two generations of success with already well established credit card companies, first with American Express (AXP) and then with Visa (V) and Mastercard (MA), bought by his two lieutenants. None of these highly successful investments had much to do with technology and none were heralded as flashy growth stocks until the compounding numbers spoke for themselves.

The secret sauce of Berkshire Hathaway’s most successful acquisitions is similarly mundane. Buffett noticed that See’s Candies was able to expand sales and earnings with very little additional capital and bought the whole company. It would be the model for several decades of capital lite businesses. Railroads had been around with little fundamental change for a century and a half when Buffett saw that their economics had improved. He noted that regulatory bodies operated by rules that required heavy capital expenditures but assured good return on that capital. The utilities of Berkshire Hathaway Energy worked similarly.

All of these major acquisitions enjoyed the same relative growth that enabled successful tech stocks to become a larger part of the S&P 500, growing to become the largest sources of Berkshire’s earnings. Unlike stocks in the S&P 500, however, they did not continue to reprice every day in the market. Once entered on the Berkshire books at the acquisition price, their growth was not reflected in valuations that rose to absurd heights. Meanwhile, their operating results have continued to pull away from less successful acquisitions and shrink the influence of Berkshire subsidiaries, which have passed the period of outstanding growth. The exemplary case is BHE, most of it bought in 1999 for $2.9B plus debt, which is now worth thirty times that, its $87 billion valuation being based on the August buyout of the 1% owned by Buffett’s designated successor Greg Abel. Its earnings over that period were up from $122 million in 1999 to $3.5 billion in 2021. It is still carried on the books, however, at the original price paid plus the price of a few bolt-on acquisitions.

The Charts And Operating Results Speak For Berkshire’s Results

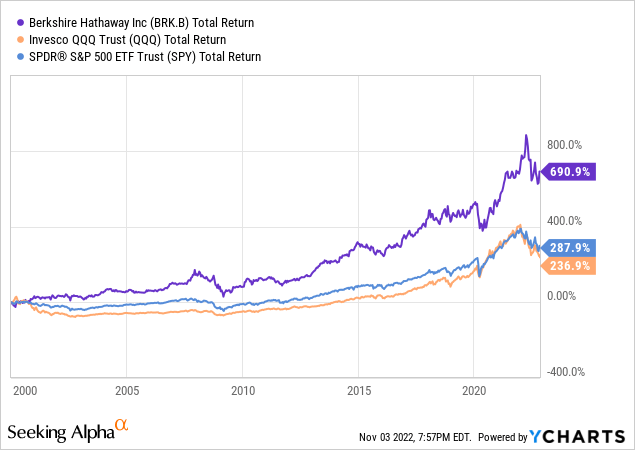

When you use Berkshire as a core holding, you don’t get anything flashy. What you get is a stable core of companies with strong moats growing at a solid pace. That is the ideal makeup for a portfolio “core.” The main thing is stability and a defensive quality, which allows an investor to add additional stocks around it. Here’s a chart showing how Berkshire Hathaway performed over an extended period compared to the Invesco QQQ ETF and the S&P 500 (SPY). The chart represents total return so that the dividends paid by the S&P 500 are fully reflected.

The starting date coincides with the period in which I chose to make Berkshire rather than an index the “core” of my portfolio. Bear in mind that charts can be made to show different things by choosing different starting points. Both the QQQ ETF and SPY ETF would be shown as the winners if the chart had begun two or three years earlier or later. In 1998 Berkshire was overvalued by about 100% and selling more than 200% of book value so that Buffett himself was discouraging investors from buying it. The QQQ and SPY had not yet begun their final ascent to absurd prices so that valuation was very unfavorable to Berkshire. I owned very little Berkshire in the two years before 2000 and did not add. That was the only time in 25 years that Berkshire was significantly overpriced compared to the market as a whole. When Berkshire spiked in the final run-up to its March 30, 2022 high (the spike on the far right of the chart) I did suggest waiting to add to positions.

In 2003 Berkshire rose persistently even as the Nasdaq 100 crashed by 80% so that a comparison starting at that point also favored the growth indexes. It did not, however, lead to immediate outperformance of QQQ and SPY as Berkshire continued to make regular gains while growth stocks were flat on their backs for close to a decade. As for the end point, the chart in the first section of this article shows that Berkshire had taken the lead firmly before the current collapse of mega cap growth stocks began.

Optionality

A dull and domestic core to your portfolio provides an opportunity to spice things up in exactly the way you choose. In the years including the 2003-2004 dot.com crash, with Berkshire as my core, I did this by buying a number of value-priced small and mid caps, which were far removed from any association with overpriced tech stocks. I also bought country CEFs of India and Brazil, which were distant from the carnage in US techs and very different from Berkshire. The country CEFs were selling at large discounts and the Indian and Brazilian markets were cheap despite good economic prospects. The important point: it was a risk I could afford to take with Berkshire as the core of my holdings. Over a couple of years both emerging markets more than doubled and the CEF’s swung to large premiums. Underlying this somewhat risky trade was the low risk steady performance I could depend upon from Berkshire.

In recent years I have added stocks in sectors not covered by Berkshire’s portfolio or wholly owned subsidiaries. Most recently these add-ons included drug distributor McKesson (MCK), which was struggling to get beyond an unfair penalty deriving from the opioid crisis, and defense stocks Raytheon (RTX) and Lockheed Martin (LMT). Again the ability to take risks was enabled by a solid and predictable core. A possible future area for portfolio addition around the Berkshire core will likely include a few foreign investments. The fact that Berkshire is mainly domestic and well insulated from international risks will again enable taking higher risks with potential greater returns.

Berkshire’s Corporate Culture Embodies Down-To-Earth Values

Berkshire is not an easy company to explain to a friend or to a group at a cocktail party. If they don’t get it already, they’re not going to get it because you tell a couple of anecdotes. Even the mythos is a bit nerdy and dull. Buffett acknowledges that he sits all day and reads financial documents. He has no interests except the financial markets, bridge, and a little golf (he made the the bid for Burlington Northern on a golf course, remember). He lives in an ordinary Omaha house bought for $31,500 in 1958 and stops at McDonald’s for breakfast paying with exact change his wife has laid out for him (I’ve tried, but my wife not only won’t do this but requires me to cut up the turmeric roots for her salad and wash all dishes; I suppose billionaires should enjoy a few perks). For years Buffett wore cheap suits until his wife put her foot down and made him upgrade, prompting the quip that he now wears expensive suits but they look cheap on him. How does this compare with the idiosyncrasies of Mark Zuckerberg and Elon Musk?

There’s a subtext to all of these stories. All suggest that money is nice but isn’t the be-all and end-all. Berkshire’s corporate culture is honest and down-to-earth. It’s about doing things the right way. It’s about not cutting corners. It’s for people who see an underlying beauty in accounting. Many employees work at Berkshire for less than they could earn elsewhere. There are no dazzling new products. There’s Apple, of course, which finally got Buffett to learn to use an iPhone, but when Buffett looks at Apple he sees numbers and lets financial writers debate the future sales and pricing of Apple products. He knew a powerful brand when he saw one.

10 Areas In Which Berkshire Has An Edge On The Index

- Berkshire is shareholder friendly. Many shareholders started as Buffett Partners as much as 70 years ago. It’s a company designed for long-term wealth building.

- Berkshire has smart, rational, and well informed long-term shareholders.

- Berkshire is balanced and rational on environmental and social issues

- Berkshire is largely a domestic company.

- Berkshire’s businesses as a whole aren’t greatly damaged by economic downturns or inflation.

- Berkshire isn’t trendy.

- Berkshire’s subsidiaries and publicly traded stocks are easy to understand.

- Berkshire’s structure is uniquely efficient in deploying capital.

- Berkshire has outstanding management at all levels.

- CEO Buffett has been conscientious in succession planning.

Conclusion

Berkshire Hathaway has worked very well for me over 23 years as the core holding of a portfolio with no index positions. Through good and bad economic times I have never had worries or regrets. It has served as the base around which to build out a portfolio. Readers should consider whether it has characteristics that align with their temperament and goals. At the current price it has value. It will rarely if ever be the #1 performing stock over any period, but it is likely to continue to be an excellent choice for solid long-term returns at low risk.

Be the first to comment