RafaPress/iStock via Getty Images

Vinci Partners (NASDAQ:VINP) is a Brazilian asset manager specialized in private equity but also diversified into public equities, structured credit, infrastructure, ESG investment, hedge funds, REITs, separate mandates and now pensions.

The company went public last year in January at a not so high price but with very short financial information on performance. Particularly, it had shown tremendous growth under a low interest rate environment prevalent in Brazil between 2016 and 2020 that came to an end in 2021.

Under that changing context I recommended a hold on the stock at $12. Now it trades at $9, but more importantly, its annual report and latest quarter data show that its funds stood the higher interest rate context relatively unscathed, both in terms of performance and in terms of outflows. Particularly interesting, this year the company released information showing significant institutional weight on its funds, providing some confidence on AUM sturdiness.

The economics of the business are great, with negligible capital requirements, zero debt and a net margin close to 45%. This allows VINP to pay dividends on most of its earnings, reaching almost $0.7 last year and $0.17 last quarter.

Note: Unless otherwise stated, all information comes from VINP’s filings with the SEC.

The Beautiful Economics Of An Asset Manager

In The Snowball, by Alice Schroeder, we learn that when Warren Buffett got serious about getting rich, he started managing other people’s assets. Reading VINP’s financial statements, I understand why Buffett took that decision.

VINP is an asset manager that started in the realm of Brazilian private equity, from there it expanded to credit, infrastructure and real estate, also in the private markets. Also participates in hedge funds, public equities and advisory.

The company says that its competitive advantage is on private markets, sourcing their own deals, and providing their clients with a broad range of alternative investment options. VINP also mentions a relatively conservative allocation strategy that any value investor might find familiar: they look for businesses with ‘stable and growing cash flows, clear competitive advantage or long term contracts and low dependence on strong economic growth’ (from the company’s latest 20-F annual report).

As of its latest quarterly report, VINP manages around R$57 billion. VINP shows on its 20-F annual report for 2021 that at least 39% of its AUM belong to private strategies (equity, credit, real estate and infrastructure), and that at least 20% belong to liquid strategies (public equity and hedge funds). Unfortunately, VINP classifies 41% of its AUM under the Investment Products category, a catch-all name for separate mandates, meaning strategies tailored for an institution or high net worth individual (HNWI) that include public and private, liquid and illiquid, traditional and alternative.

According to VINP, at least 47% of its assets have lock-up periods higher than five-years, belonging to either one of the private strategies or to the closed-ended publicly traded funds the company manages.

In terms of clients, VINP caters mostly to big fish, with 57% of AUM provided by institutions, and 23% by HNWI. This provides some certainty regarding AUM, because institutions and HNWI are not so prone to invest and disinvest at the movement of markets and interest rates.

However, this does not mean VINP has no client risk. Institutions and HNWI will move their business elsewhere if they believe VINP is not delivering value. In VINP’s business, client relationships can be worth billions each. The 10% largest institutions hold 52% of institutional AUM in VNP. The 10% largest HNWI hold 84% of AUM in the category.

VINP obtains revenues from two mechanisms. The company charges management fees on its AUM and also obtains performance fees if the funds surpass their particular benchmark. Both kinds of fees are determined when each fund is established.

Additionally, VINP has an advisory service that helps other companies structure their financing. From this business VINP also generates fees, R$60 million last year. This business segment is more volatile, as we will see for the last quarter.

In terms of costs, VINP’s biggest expenses come from its core employees, meaning the fund managers and salespeople. Personnel and profit sharing expenses totalled R$150 million last year, or about 33% of revenue.

Profit sharing is a big portion of those expenses, accounting for R$100 million last year, almost half of all expenses. According to our calculations, profit sharing moves in line with revenue, which is both good and bad, because that removes operational leverage.

In terms of capital, VINP has a negligible footprint. In order to manage those R$57 billion, VINP needs three leased offices that cost R$22 million a year.

Overall, operating expenses totalled R$222 million last year, against net revenues of R$465 million. That comes to an enviable operating margin of 52%.

Operating leverage does play a role in VINP’s earnings but with at least 20% of revenues becoming variable expenses, it is not tremendous.

On the financial side another of VINP’s strengths comes out.

The company did not spend a big portion of the proceeds from its IPO yet, and holds about R$1.3 billion in financial assets. These are mostly VINP’s own funds, particularly credit funds that try to match Brazil’s central bank’s rate. VINP also does not have any financial debt and meager liabilities, mostly related to its leases. Therefore, the company has a fourth source of profits on these assets. Last year they provided about R$28 million.

The last piece of magic comes at the tax level. While Brazil’s corporate income tax is 33%, VINP has paid only 20% at the consolidated level for the last three years. The difference is explained by VINP’s usage of a regulation called presumed profits, where VINP’s subsidiaries can declare profits based on a pre-established rate over revenues. Because VINP’s subsidiaries’ earnings margin is higher than the presumed rate, they pay less taxes.

Overall, VINP is able to come up with a 45% to 50% net earnings margin, totalling R$200 million in 2021.

Because VINP has negligible capital investments and no debt, most of those revenues are free cash flow. Not all of them, because some of the performance revenue is earned but not realized until the corresponding strategies are terminated. VINP has announced this year that it plans to pay in dividends 75% of its distributable earnings (meaning those that are cash solid) or 100% of its earnings, whatever is less. In the second case, it will also purchase its own stock to reach 75% of distributable earnings. Last year for example it purchased R$50 million and another R$22 million last quarter.

What’s The Catch?

If the business is so good, why did I not recommend the stock last year?

The main reason was that VINP’s strategy is based on the thesis that low interest rates will make Brazilian institutions move towards higher yielding assets, and therefore towards VINP’s management. According to VINP, Brazilians and their institutions are used to relatively high real interest rates, and therefore are not used to investing in other kinds of assets.

That thesis had been true, particularly since 2016 when the Brazilian government started to cut the interest rate to fight the recession the country had been in, and until 2020 when those cuts reached a limit of 2% to fight the pandemic. During that period VINP’s AUM more than doubled, particularly after 2018, growing at a CAGR of 36%.

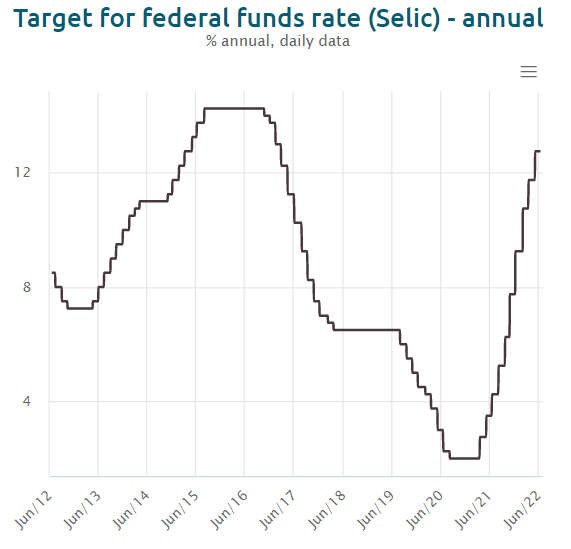

The problem last year was that as I was writing, there were substantial doubts about the low interest rate context chances of surviving. Indeed when I wrote the article the SELIC rate (the main Brazilian rate) was at 7% from 2% in 2020. The SELIC rate closed last year at about 10% and today stands at 13% and rising.

Brazil’s SELIC interest rate (Brazil’s Central Bank)

My doubt then was that higher rates would make VINP’s AUM recede to a much lower level, therefore affecting profitability. With lower profitability then, more risk and a higher price, my recommendation was a hold.

Today I have more information.

First, VINP has released more information about their client base in their 2021 annual report, showing that most of them are institutions and HNWI, meaning less volatile clients. In my opinion, institutions are not going to pull all of their funds if rates rise unless they understand it is going to be a relatively permanent movement. According to VINP, the Brazilian neutral interest rate is between 3% and 4%, meaning a current 13% should domesticate inflation and then return to lower levels.

Second, and most importantly, VINP won funds last year, instead of losing them. Data from 1Q22 shows that on a YoY basis, net fund inflows were R$2.2 billion. Although last quarter was not so good, with net fund outflows of almost R$900 million, it is not terrible, considering rates that high, the war in Europe and markets collapsing.

At the profitability level, 1Q22 data shows revenues 12% lower than in 2021, when the interest rate hikes had not started yet. Operating profits did get a hit, 30% lower than last year. But the financial assets mentioned previously improve the outlook, with net earnings closing at the same level as 1Q21.

Particularly hit were performance fees and advisory fees, falling 75% YoY. This is understandable given the market situation we are under.

It is probable that VINP will see more outflows this year, considering that 2Q22 has been a massacre in public markets, that rates are still on the rise in Brazil, and that Brazil is facing political volatility with a polarized presidential election coming in October.

However, last year showed that those outflows should not become a drain on AUM, and therefore should not affect profitability significantly.

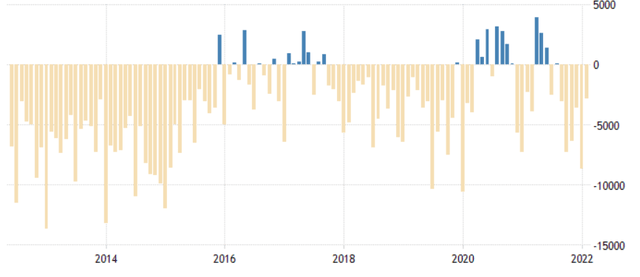

From a recession and flow to quality perspective, this has never been a problem for VINP. According to TradingEconomics with data from Brazil’s Central Bank, during most years when VINP grew its AUM and particularly in those that they grew faster, from 2018 and 2020, Brazil showed a capital account deficit.

Brazil’s capital account monthly (TradingEconomics with data from Brazil’s Central Bank)

Additional Risks

There are two additional risks that did not fit previously.

First, VINP is a company controlled by a single owner, Mr. Gilberto Sayao, with 14 million class B shares, over a total of 56 million shares, but representing 77% of votes. Directors and executives as a group have a 50% stake in the company. Depending on the investor this can be considered good or bad.

According to the company’s 2021 annual report, these shareholders are forbidden to sell until 2023, and after that they as a group cannot sell more than 5% of the company’s outstanding stock. This is definitely a plus.

Second, VINP has found material weaknesses in its internal financial control. Previously those weaknesses had been found on revenue recognition. Last year the weaknesses were found on complex deals and reporting, without mention of specific areas. The company said those weaknesses did not materially affect the financial statements.

Conclusions

What is the risk? That more volatile markets and higher interest rates in Brazil and globally generate significant outflows from VINP’s funds, reducing VINP’s earnings too much below the paid price. If a global recession ensues, then VINP may take a long time to recover. I do not expect any collapse risk given that the company has a lot of liquidity, zero debt and a lot of margin before entering negative territory.

In the current bear market and with the ghost of a recession in front, the question moves towards resiliency. I consider VINP to be resilient. Consider zero performance fees and zero advisory fees, to concentrate on AUM alone. The company has about R$120 million in expenses that are not dependent on performance, and 20% of revenues are shared with employees. That means that revenues can fall to R$150 million a year before the company is on the red line. Those revenues represent R$15 billion in AUM or a 74% fall from current levels. How many companies can see a 75% fall in revenues before showing losses?

What is the price for that risk and that resilience? Currently it is $500 million for a company that generated $8 million in operating profits from a single line of business last quarter and $9 million in profits considering its financial assets. Annualized that comes to $36 million, or a PE of 14. The company pays most of that as dividends or repurchases, therefore there is a direct channel to appropriating those earnings. If that is the case, the current dividend/payback yield stays around 7% to 8%. From a PE perspective the company is expensive, but from a dividend perspective it is not.

What is the bright side? With similar or lower rates and a market that starts recovering maybe this year or the next, VINP can continue growing. The company showed that it can sustain at least temporarily high interest rates and also that it can sustain relatively permanent capital outflows from Brazil.

From my perspective that means that VINP does not need a good economy to have good business (like ARCO for example), but rather a not so terrible economy like a global recession.

Add financial strength in the order of $200 million net cash after paying all liabilities, and capacity to pay a high payout ratio, and it seems a good risk/price ratio to me.

Be the first to comment