qunamax/iStock via Getty Images

Our great experiment in monetary economics continues.

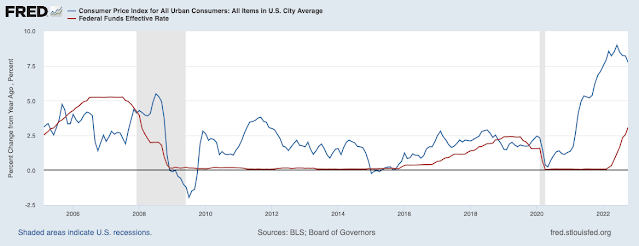

BLS, Board of Governors

The news of the moment is that inflation might-might-be peaking. I just present the CPI to make the point, but there seems to be a lot of news suggesting that inflation is easing off. Jason Furman’s Twitter is a great source of up-to-the-minute detailed data and analysis suggesting this view.

Of course, this could also be a blip like August. And new shocks could come along. But let’s explore what peaking might mean.

As I’ve written before (WSJ oped, “expectations and the neutrality of interest rates,” short version, “Inflation past present and future” “Fiscal histories” and many more) we are in the midst of a grand experiment in monetary economics. The core question: is inflation stable or unstable under an interest rate target?

Traditional theories and most conventional policy analysis state that inflation is unstable under an interest rate target. If the interest rate is below the current inflation rate, inflation will spiral upwards. Inflation cannot come down until the interest rate is above the current inflation rate and stays there. By this theory, inflation should still be spiraling up.

Newer theory, which primarily uses rational (better, forward-looking or model-consistent) rather than adaptive expectations, says that inflation is stable under an interest rate target. It follows that inflation can go away all on its own, even with interest rates substantially below inflation.

With fiscal theory + rational expectations, we are having a burst of inflation to devalue government debt, as a response to the 2020-2021 fiscal blowout. But once the price level has risen enough to bring the real value of debt back, it’s over. Until the next shock hits.

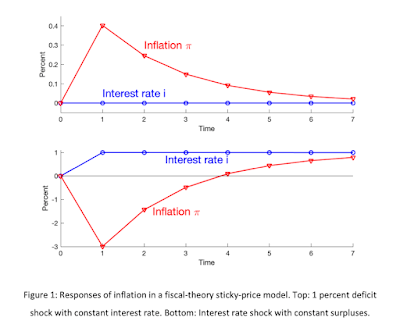

This graph from Fiscal Histories illustrates:

Author

The top graph illustrates what happens in response to a fiscal shock. There is a bout of inflation which devalues debt. But it goes away eventually even if the Fed does nothing, as in that simulation. The bottom graph says that the Fed can help in the short run by raising interest rates, offsetting some of the inflation at the cost of larger future inflation.

Well, if inflation fades away despite interest rates below the inflation rate, we have a rather striking confirmation of this rational expectations view, with stable inflation, relative to the traditional spiral-away view. So, are we headed there? It’s too soon for this cautious commenter to declare victory, but I am willing to provide context and say I’m watching anxiously!

I read that a bit in the writings of commenters in the traditional style, such as Furman, Summers, and Taylor. Though calling for higher interest rates, none seems to call for interest rates substantially above 8% (current inflation) or the 12% or more than a Taylor rule might recommend. A few more increases to 4 or 5% are enough. They seem to view that the “underlying” inflation is lower, 4 or 5%, and also note that inflation expectations as measured are still in that range – direct evidence against the adaptive expectations view underlying the traditional spiral. (I don’t have links, so apologies if I’m characterizing their views wrongly. This is aggregated over several months.) Well, a return to 4 or 5% is also what the top simulation suggests.

I say “second” experiment because we’ve been here before. See above, 2008. (Sorry for repeating the point, faithful readers.) Then, we had deflation below the interest rate, the Fed couldn’t move, and the traditional view said deflation spiral. That didn’t happen either.

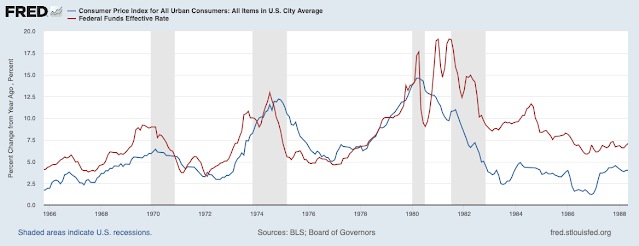

The 1970s are the other interesting piece of history.

BLS, Board of Governors

1980 is the poster child for the view that interest rates must be substantially higher than inflation before inflation will decline. But look harder at 1975. Inflation did go down, on its own, with interest rates that never exceeded inflation. Inflation didn’t get all the way back to 2%, and then rose again. One can argue about just why. But the simplistic view that inflation will never decline until interest rates are substantially above inflation wasn’t really true then either.

Usual disclaimer: all of these dynamics presume there isn’t another inflationary shock. The chance of a budget blowout seems small right now, but a bad turn in Ukraine, Taiwan, the Middle East, or elsewhere could knock over the lab table. There is also a delicate question whether, having crossed the fiscal rubicon, even “smaller” current deficits are inflationary.

Editor’s Note: The summary bullets for this article were chosen by Seeking Alpha editors.

Be the first to comment