AlexSava/iStock via Getty Images

Where do returns come from?

I spent years pondering this question as the actual source of returns is remarkably disconnected, both temporally and quantitatively from the realization of returns. At first it seems like a simple question with a simple answer: Total return is measured by summing dividends and capital gains (realized and unrealized).

Sure, but where do capital gains and dividends come from?

Let me begin with looking at how market capitalization interacts with capital gains.

2 pathways for market cap expansion

There are 2 ways in which the market capitalization of a company increases:

- Equity issuance

- Price increase

The first is quite straight forward and it is easy to track where the money is coming from. A company issuing 1 million shares at $10 per share is receiving actual cash inflows of $10 million (minus underwriting costs).

Thus, the $10 million rise in the market capitalization directly corresponds to $10 million more dollars invested in the company. However, shareholders now own a smaller portion of that company so such issuance does not directly create capital gains.

The market cap increase that happens when market price increases is a bit more nebulous.

Money out of thin air

The market cap of all U.S. equities is about $48 trillion. On any given day stock prices will move varying amounts but let us consider a 2% up day. Suddenly the market cap of all U.S. equities is about $49 trillion.

Where did that extra trillion dollars come from?

It gets even stranger at the individual stock level, particularly among low liquidity issues. Consider a $1B market cap stock trading at $5 per share. If someone buys a single share of this stock at $10 and that is the most recent trade, the market cap is now $2B. In this instance, a single $10 transaction created an extra billion dollars of market cap.

What this tells us is that paper gains from mark-to-market aren’t real. They can be manifested out of thin air and yet it is this sort of pricing gain that creates capital gains. A paper gain becomes a real gain when the stock is sold for the realized capital gains.

As market capitalizations increase from price increases an investor can sell at the now higher price to generate returns.

This concept incorrectly leads many to believe that changes to market price are the origin of returns. I can’t count the number of times I have heard investors reference a company doing well as they point to the stock price or suggest that a company is failing because the market price has dropped.

The causality goes the other way. It is increases or decreases in intrinsic value that cause the corresponding change in market price. It is just not always matched up in real time because the market is inefficient.

It is crucial to firmly grasp the direction of causality here as failure to do so results in falling victim to a Ponzi scheme.

Capital gains realization – legitimate versus Ponzi scheme

Both a legitimate capital gain and a Ponzi scheme involve buying something and then selling it for more. Both also generate returns for the investor when successfully executed in this fashion.

So, what is the difference?

A legitimate gain is one that is backed up by intrinsic value while a Ponzi scheme relies on selling above intrinsic value. Some lucky and opportunistic people may get to sell at the high price, but only by passing off the worthless shares to someone else who will eventually suffer. The magnitude of losses incurred equates to the capital gains enjoyed by those higher up in the pyramid.

With legitimate capital gains, the gains come from true returns and there are no offsetting losses suffered by someone else. This gets us to the true origin of returns which is the actual profits made by the company. It all begins with property law.

Property Law – the mechanism by which shareholders actually own a company

In buying a share of a publicly traded company one is acquiring ownership of that company equal to the percentage of shares outstanding that they buy. U.S. laws protect this ownership such that you are entitled to your pro-rata share of the profits derived from the company.

The mechanism of transference is quite straight forward for private partnerships in which 3 owners each have 33.3% of shares as they each can directly get 1/3 of the profits. It gets a bit messier in the public market when there are thousands or even millions of shareholders.

Certain rights become hard to enforce. Technically the board is appointed by shareholders so shareholders are deciding what portion of the profits to pay themselves as dividends, but an individual shareholder may not have a sufficiently meaningful portion of the votes to have any real power.

Due to widely differing payout ratios, dividends don’t necessarily reflect profits. A company can earn $5 per share and not pay a dividend while other companies have negative profits and pay dividends. If one loses sight of the property law that makes them a true owner of any company in which they hold shares it can certainly feel like intrinsic value doesn’t matter. When the company’s earnings rise the shareholder might not be seeing any of those profits in real time.

That is why so many have ignored fundamental based investing and instead resorted to gambling by trying to flip things for quick gains or even investing in things that don’t have any profits. However, there is one powerful tool that fundamental investors have that non-fundamentals do not – waiting.

The power of waiting

Market prices can be wildly disconnected from intrinsic value, but over the long run there are powerful mechanisms that pull market prices toward intrinsic value.

- Buyout of company creates a realization event at a price that usually approximates or exceeds intrinsic value

- Share buybacks in which a company pays shareholders for their shares so as to consolidate ownership

- Dividends – a powerful mechanism even when a company doesn’t pay a dividend

When a company does not pay a dividend, earnings are still earned. The retained capital is reinvested in the business which accelerates future earnings. In turn, this means that the dividend when it is eventually paid is much larger.

Consider that Microsoft (MSFT) did not pay a dividend until January of 2003. Those who held before then were still handsomely rewarded with dividends.

This concept of a company not paying a dividend in order to pay a much bigger dividend through the retained earnings is often lost because of the way the market talks about dividends as a yield rather than in absolute dollars.

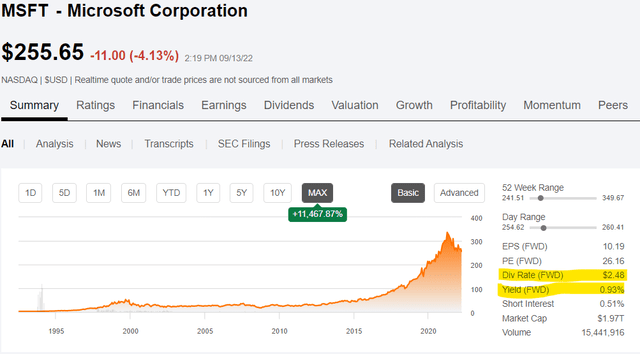

Thus, Microsoft does not seem to pay a big dividend as the yield is only 0.93%.

But that is on today’s price. To someone who held back before Microsoft paid a dividend, that is an enormous dividend against their cost basis.

In fact, if you held in the early 90s that would be a roughly 102% annual dividend against your cost basis.

That is the mechanism by which intrinsic value forces market prices to move toward it. It so happens that Microsoft went up 11,467%, but even if it hadn’t, shareholders would have still been rewarded with a truly massive dividend.

Hopefully that makes clear the difference between the capital gains of a Ponzi scheme and the legitimate capital gains of a fundamentally backed investment.

If the market price drops before you can sell on a Ponzi scheme you are screwed. The money will never be recovered.

If the market price drops before you can sell on a legitimate fundamental investment, you can just wait and get the return later via dividends.

The origin of returns

The mechanism of transference is complicated and returns can be lagged temporally, but the true origin of returns is earnings. When properly handled by a good company, earnings reliably create shareholder returns.

With a proper understanding of this process and the power of waiting one can profit from the noisy market rather than letting market noise distract from their investment.

Market price represents 2 things:

- The amount you can pay to obtain ownership of a company

- The amount for which you can sell your ownership of a company

Taking advantage of market inefficiencies is quite simple. Only buy when the market price is less than the intrinsic value of ownership of the company and only sell when the market price is greater than the intrinsic value.

Be the first to comment