Panuwat Dangsungnoen

Introduction

Over the years that I’ve been writing about stock investing, I’ve noticed a recurring problem that leads investors of various types to produce below-average returns. Since I view one of my most important jobs as helping retail investors to improve their investment returns, I feel compelled to write an article that focuses on the particular problem of investors not having explicit overall return goals in place, either for the individual stocks they are buying or for their portfolios. And this lack of standards leads to trouble for many investors.

It doesn’t matter if one’s return goals are in the form of total returns or collected dividends. The question of one’s medium and long-term return goals is still extremely important and needs to be asked before one starts buying stocks. However, because dividend and income investors tend to think differently about what matters (total returns or income) I will examine two separate ways of setting return goals for both investing approaches in this article. Since I’m a total return investor, I will first start by examining the total return goal question, and then later on I’ll share a good method of setting dividend return goals as well that is probably quite different than what most dividend investors are using.

My total return goals

I figure if I’m going to lecture investors about not having return goals it makes sense for me to first share my total return goals and how I came about setting them. Over most full economic cycles that include at least one recession, I aim for total returns at the portfolio level of 15% to 20%, including any cash drag if I decide to hold cash at certain times. Currently, since starting my marketplace service, The Cyclical Investor’s Club, in January of 2019, about 3.5 years ago, I am right around the 15% CAGR return level. This is about the same as the S&P 500 index over the same time period. However, my returns include a cash drag where I held an average of nearly 50% cash and metals from March 2020 through October 2020, and also an average cash drag of about 10% for the year 2021, which were big up years for the market. So, I’ve been able to achieve S&P 500-like returns that also meet my long-term return goals while being much more defensive than the index on average. Currently, I’m holding about 1/3 cash, so I continue to be more defensive than the index as I write this article.

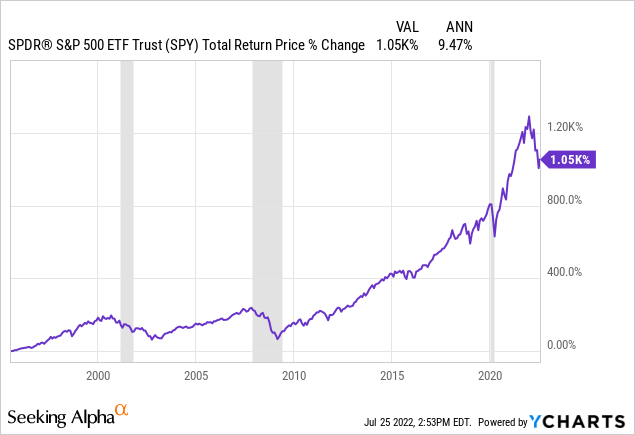

I came up with my total return goals by first examining the average return of the S&P 500 index in modern times, which is roughly 9-10% per year.

If I was going to invest with the goal of returning 10% per year, it makes sense to simply buy the index over time like a Boglehead, and cross my fingers that history continues on a similar path that it has the past 20 or 30 years.

At the other end of the spectrum, we have Warren Buffett and Berkshire Hathaway (BRK.A) (BRK.B), who is often regarded as one of the best investors in the world, and he has returned a 20% CAGR over the span of about 50 years. I think this provides a good historical framework where one can say that less than 9% or 10% annual returns is below average, 10% to 15% is above average, 15% to 20% is among the range of the very best investors over the long term, and expecting consistent long-term returns over 20% per year probably means you will have to take on considerable risk and get lucky in the process. Since I don’t want to rely on luck, and I don’t think I’m smarter than Warren Buffett, I have decided to use a 15% to 20% range as my long-term return goal. It is high enough that it makes it worth my time to learn how to analyze stocks and manage a portfolio, but it is low enough that it won’t require excessive gambling and reliance on luck in order to achieve.

Why setting total return goals is important

There are many errors an investor can make when analyzing a stock, but not having an overall total return goal or threshold for a full economic cycle (or at least the medium-term of 2-5 years) is the error I see most otherwise good investors often make. And it’s the biggest structural mistake that investors make at the strategic level. I see the mistake manifest both at the level of expecting too much in the form of open-ended, sky-is-the-limit return expectations, and I also see it manifest itself with investors who choose to focus on something like dividend income instead of total returns, or who use return expectations relative to 10-year Treasury yields, instead of using absolute return goals. Let’s examine all of these examples.

18 months ago many new investors who had piled into recent IPOs, SPACs, pandemic winners, crypto, and tech disruptors were sitting on massive gains in their portfolios. I’ll use ARK Innovation ETF (ARKK) as a poster child for this sort of investing. In 13 months, from January 2020 through mid-February of 2021 ARKK was up 212%. Keep in mind that this is not an individual stock. This is a collection of a group of stocks. There is no way that anyone who understood that the average annual return for the market is 10%, and the average annualized return of Buffett, one of the best investors ever, has been 20%, could honestly think that a 200% annual return was realistic or could last. Simply having a realistic understanding of return goals should have caused an investor who got lucky enough to own a portfolio like ARKK’s during this time to take profits. After all, they just got nearly a decade’s worth of returns in one year.

Understanding what is realistic and having a frame of reference makes it much easier to dismiss bombastic claims of crypto pushers and SPAC dealers out of hand without a second thought, especially at the portfolio level. But if an investor doesn’t have any realistic long-term return goals then it’s much easier to believe the easy money hype. The truth is, unless you start with a lot of money, it takes a long to build wealth even with 20% annual Buffett-like returns. Most “billionaire” hedge-fund managers don’t get rich on their investments. They get rich on their fees. An understanding that 20% annual returns are likely the best you’ll be able to do long-term can keep you out of a lot of bad speculative investments.

For seasoned investors, this is all pretty obvious and usually, investors with more market experience are less susceptible to get-rich-quick promises in the market. However, the older an investor gets, the more susceptible they seem to become to the opposite problem. They tend to be willing to pay a very big premium for “safe” investments. And when they do this, they sacrifice returns at the other end of the spectrum because they also aren’t setting clear total return goals.

I’ve written so many articles over the years where I share that the likely long-term returns of a stock that is trading at a certain price are going to be in the low-single digits of 2% to 5% per year. And in the comment section, I typically get responses about how high quality the business is or how long they have been paying dividends and how that is enough to justify holding the stock. Well, if your total return goals are 2-5% per year, then sure, that’s okay. But I don’t think if most investors had set their return goals ahead of time before they started buying stocks they would set them in the low single-digits.

Often at this point, the conversation shifts to dividends rather than total returns, and I am told that the investor only cares about the dividend income. Okay, that’s fine, but the same rule applies to dividends. First, we need to assume that the overall portfolio at least doesn’t lose money on an inflation-adjusted basis. I mean, any business can take your money and then slowly pay you back 80% of what you gave them in the form of an 8% dividend for 10 years before going bankrupt. I don’t think paying $100 in order to get $80 returned over a decade is anyone’s goal. But once we move beyond these dangerous high-yielders, it’s worth asking what sort of dividend yield and dividend growth rate an investor requires to meet their return goals. For what it’s worth, I actually have a technique for measuring this myself as well, and I call it “Dividend Time Until Payback”. This is how long it will take to earn an amount equal to my investment back via only the dividend and dividend growth. My threshold for this is 10 years or less, and the business has to have positive earnings growth as well. If it takes longer than 10 years to earn my investment back then the stock is too expensive to buy based solely on the dividend income.

I track about 70 high-quality dividend aristocrat-type stocks using this valuation method. The median time until payback on this group right now is 22 years. That’s how long it would take to earn $100 in dividends from a $100 investment. I simply don’t know anyone who, if they were starting from scratch and setting their goals ahead of time would say “If I can find an investment that will pay me back an amount equal to my principal in 20 years, then I will be a buyer.” Yet, somehow, that is what dividend and dividend growth investors have been doing for several years now. Overpaying for safety might not be as obviously dangerous as what the speculative growth investors are doing, but it’s still a strategy that is unlikely to produce above-average returns.

How did we get here, and what’s the solution?

I think we’ve largely gotten to this point in the stock market because of low government bond yields. Because bond yields have been extremely low for a long time, if an investor uses the 10-year treasury yield as their “risk-free” rate comparison for a stock investment, then stock valuations look comparatively more attractive. For example, if I write an article where I show Walmart’s (WMT) likely long-term returns are going to be about 5% per year over the next decade if a person buys or holds at today’s prices, if the 10-Year Treasury yield is at 3%, an investor can respond that 5% is better than 3% and at least there is a chance that Walmart can pass on inflation if we happen to get it, when the bond if held to maturity, will not. This situation makes investors willing to pay more for stocks. And, I think it tends to make them pay more for two types of stocks in particular.

The first is well-known high-quality brand name stocks that they feel are basically “safe” to own for a long period of time. If one is receiving only a 3% yield from a bond, then it will take about 23 years to double their money. That’s actually a little longer than the median dividend aristocrat’s dividend yield and growth right now of 22 years. So, it’s not that dividend investors are being entirely irrational in what they are paying relative to bonds.

The second effect of low bond yields is on growth stocks with very high valuations because they have the opportunity to grow into their valuations over the long term. If it takes 23 years to double one’s money in long-term bonds, then that potentially provides a very long comparative runway for a business that is growing earnings at 20% per year or more. A valuation that looks crazy expensive right now based on current earnings, might look quite cheap 20 years from now because the “E” part of the P/E has time to grow and compound a lot. The difficulty with these stocks is that it is very hard to predict earnings 20 years into the future, and as businesses get bigger, it’s harder to grow earnings at very fast 20% annual rates because the total addressable market eventually gets addressed. This often gets forgotten by the market though, and whatever the recent growth trend of the past year or two has been, tends to get extrapolated out far into the future. It’s easier to justify extrapolating far into the future on a relative basis if bonds must be held far into the future in order to double one’s initial investment as well.

The problem with all this, of course, is that it assumes very little will change over the next 10 or 20 years. We’ve had a period of nearly 40 years of falling interest rates and 20 years of low aggregate inflation. We’ve also had a 30-year period with a very big historical shift toward globalization. Those periods are long enough that many investors haven’t experienced times that are any different than these. Sure, we have had recessions during this period, and those are periods where valuations have dropped. But we haven’t had much inflation, we’ve had lots of globalization, and we’ve had consistently falling interest rates. The longer an investor has to hold their investment into the future before doubling their money, the more time there is for things to change from the recent historical patterns.

The solution to this, in my opinion, is to have one’s return goals (either for total returns, or the time it takes to double one’s money via income from dividends or other sources) set independently of bond yields or discount rates. My view is that if we take a long enough time period, like Berkshire or the S&P 500’s 50 years, then we can see what sort of returns are possible. Inflation has averaged roughly 3% over the long-term in the US, so we can assume a rough estimate there as well.

Investors can, of course, set those return goals at whatever expected rate of return they want. The biggest issue that I experience when communicating with investors is that they don’t have rate of return goals at all. This leads to investors simply paying too much and accepting returns that are unlikely to meet their needs and expectations over the long-term.

Will prices ever fall low enough to produce great returns?

Maybe there is a reader out there, who has decided that I make some good points in this article and that they should more explicitly state their return goals and only buy stocks when they are expected to meet those medium or long-term return goals. Now the most difficult part begins. Because we haven’t had a “normal” recession or bear market since 2008/9, it perhaps makes it difficult to think about the potential opportunities that the market is capable of offering up on occasion. And it is very difficult to know when we will have bear markets and just how deeply stocks might sell off. That is why investing is hard.

However, history has shown that recessions and bear markets have always been with us and that conditions are always subject to change. And we know that over very long periods of time an average market return is about 10% per year. So, at the very least, it makes sense to not hold onto stocks when their earnings trends and price point to returns that are significantly less than that, and it makes sense when future returns are likely more than 10% over the medium or long-term, to consider buying some of these stocks. And it’s also fair to assume every 5-7 years there will be a year when valuations are considerably better than other times. Managing the details of all this in order to get the very best returns is difficult to do and it takes some skill. But at the extremes, it really doesn’t take much skill. It didn’t take much skill to know that ARKK was crazy overvalued. It doesn’t take much skill to know that a sub-2% dividend yield, isn’t likely to be a good dividend investment unless the dividend grows at an extremely fast rate for a very long time, so it’s not a good dividend investment. One shouldn’t expect it to take 20 years to earn one’s money back on an investment, because it’s impossible for anyone to predict an individual business’s prospects that far into the future.

So, I am usually willing to take my chances when it comes to waiting for the market to give me good valuations before I buy. I’ve purchased around 100 stocks during the past three years even with my fairly high return goals. However, I currently use five different investing strategies and combine them together and that helps me find different types of opportunities in different market environments. Right now, high-quality dividend-paying stocks are desired by the huge Baby Boomer demographic entering their retirement years, so there aren’t many deals to be found right now in that category of investments. But there are other areas where an investor can also invest that might be overlooked. Having the flexibility to find good returns wherever they are is important. Even though I’m holding about 1/3rd cash right now, I’m still buying stocks. For example, in May I bought four fast growth stocks, including Airbnb (ABNB), and I also bought a very beaten-down Netflix (NFLX). I’ve written “buy” articles in recent months about Silgan (SLGN), Global Payments (GPN), and Comcast (CMCSA). Other stocks like Jack in the Box (JACK) are trading at reasonable valuations. So, even though I’m holding a significant amount of cash due to my current expectation for a recession roughly around Q1 2023, I’m still finding things to buy on occasion. They just aren’t the super popular dividend or mega-tech names. And I’m sure some of them won’t be great investments. But they at least have a reasonable chance to produce the 15-20% medium-term returns that I aim for.

Conclusion

Not having clear return goals, whether based on earnings, market sentiment, or dividends, is a recipe for achieving poor returns. I don’t expect every investor to have goals as high as mine, but it also doesn’t make sense to have goals that are significantly below the average long-term returns the market has produced in the past. And while we never can say for sure if the market will push prices low enough to meet high return goals like mine, if an investor develops diversified valuation techniques they can analyze a wider variety of opportunities. I have five total valuation techniques that I use. One is earnings based, for cyclicals I use a method based on historical price patterns, for REITs I have a long-term momentum strategy, for dividends I use my years until payback approach, and I also have a valuation technique for fast-growth stocks that is different than what most growth investors use. In addition to these, I place everything in the context of the macro environment as well, so I usually have an opinion about where we stand in the macro-economic cycle and that can influence how I approach each individual valuation technique. What this all amounts to is that while I can’t control whether the market will give me good deals at any given time or not, I can cover a wide variety of potential opportunities, so that if a certain type of stock is overvalued, like high-quality dividend stocks, then I can potentially find value in other areas, like cyclicals or fast growth stocks, or non-dividend paying high-quality earnings stocks. This scope allows me to be more selective within each category and also to aim for better prices and valuations in each category than if I limited myself to only investing in one category of stocks.

So, first, I encourage investors to have some sort of return goal that is at least as high as the market average. And second, I would encourage investors not to invest too narrowly because that can severely limit one’s opportunities and what tends to happen is investors’ standards slowly creep down, either by buying lower quality (think ultra high-yield stocks) or by paying prices too high to produce good returns.

I would be very interested to hear your medium or long-term return goals in the comment section, and why you decided on those goals.

Be the first to comment