mars58

As then-chair of the GIC central banking series, I watched the euro from the moment it was born. In fact, I recall the original currency exchange rate setting in 1998 as the terms of the Maastricht Treaty were implemented. (For that history, see “Maastricht Treaty”)

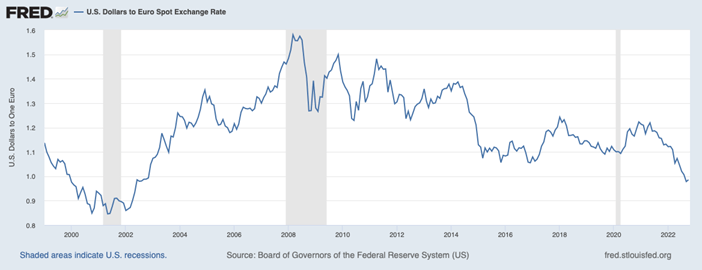

Here’s a chart of the entire history of the exchange rate between the US dollar and the euro.

U.S. Dollars to Euro Spot Exchange Rate, 1999–2022

For the first three years of the euro, ECB members maintained their own paper currencies while also achieving a virtual conversion to the new euro. A consequence hidden from view was that the three years allowed the “dark money” cash balances held in various currencies to segue out of them until the new euro was post-virtual and the transition completed.

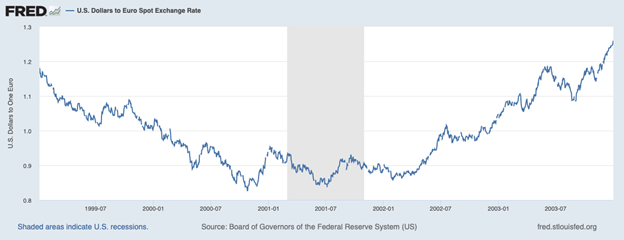

So the euro had three years of weakening on the foreign exchange market against the dollar and yen and others like the Swiss franc. In its first three years, the euro went from $1.18 on day one to 83 US pennies at the very weakest.

U.S. Dollars to Euro Spot Exchange Rate, 1999–2003

Once the transition to a fully functional currency was completed in 2002, the dark money returned home and the euro strengthened against the dollar and eventually reached a level of $1.60.

Meanwhile the Eurozone started to expand from the original six member countries (Belgium, France, Germany, Italy, Luxembourg, and the Netherlands). And then it began to waive the policy initiatives that had originally made the euro a strong currency.

The entry of Greece was a seminal event, since the Greeks admitted after entry that they had “misstated their economic numbers” (“Greece Admits Faking Data to Join Europe“). By then, however, they were in, and there is no provision in the Eurozone rules to throw a country out without a high penalty. That’s why it has never happened.

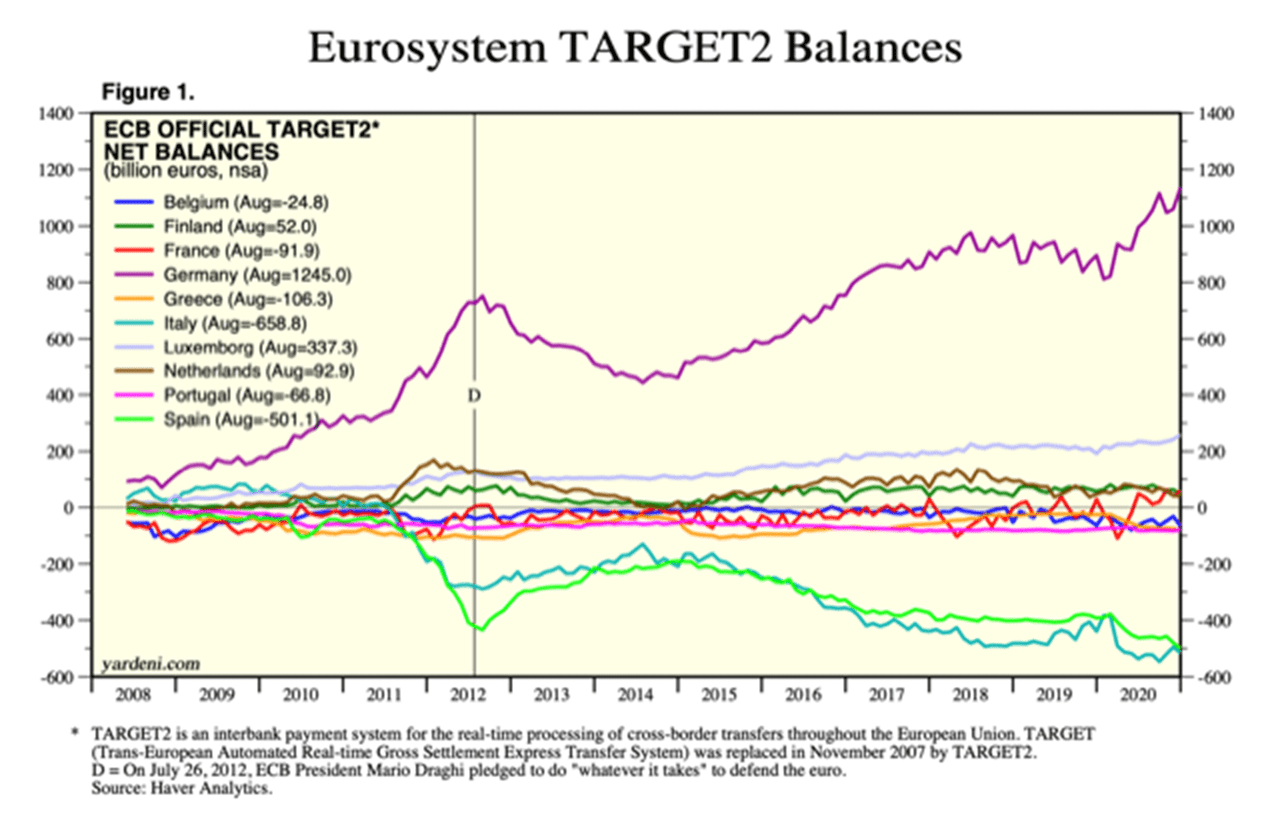

Eurozone liabilities among and between the member countries are settled in a payment system known as TARGET2, which stands for “Trans-European Automated Real-time Gross Settlement Express Transfer System 2.” Over time, that system has morphed into one where there is a huge liability on the part of Italy and a large offsetting contingent claim by Germany.

See Ed Yardeni’s discussion and explanatory graphics: “Money & Credit: Eurozone TARGET2”. The first chart in the document shows the official TARGET2 net balances in the pre-Covid timeframe:

(Source)

For readers who wish to know more about TARGET2, we suggest three additional references.

(1) The Bundesbank discusses the mechanisms of TARGET2 and how the balances work. “TARGET2 – Balance“

(2) The ECB offers a primer on TARGET2. “What is TARGET2?”

(3) CEIC shows Italy’s declining TARGET2 balance over the past year.“Italy IT: TARGET 2 Balance: Outstanding”

TARGET2 is a contingent liability, which means nothing as long as the lender countries are willing to continue to extend more and more credit to the creditor countries. Since these loans will never be repaid, the process has become open-ended and without limitations.

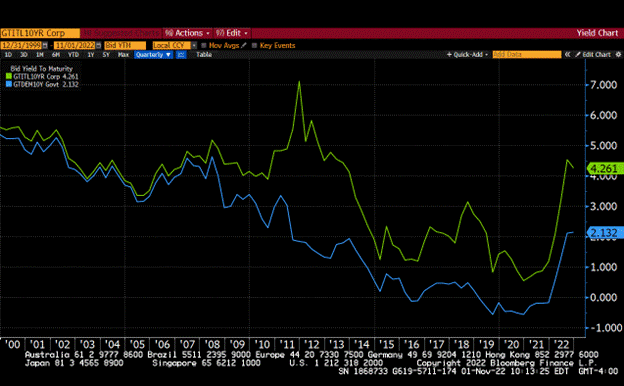

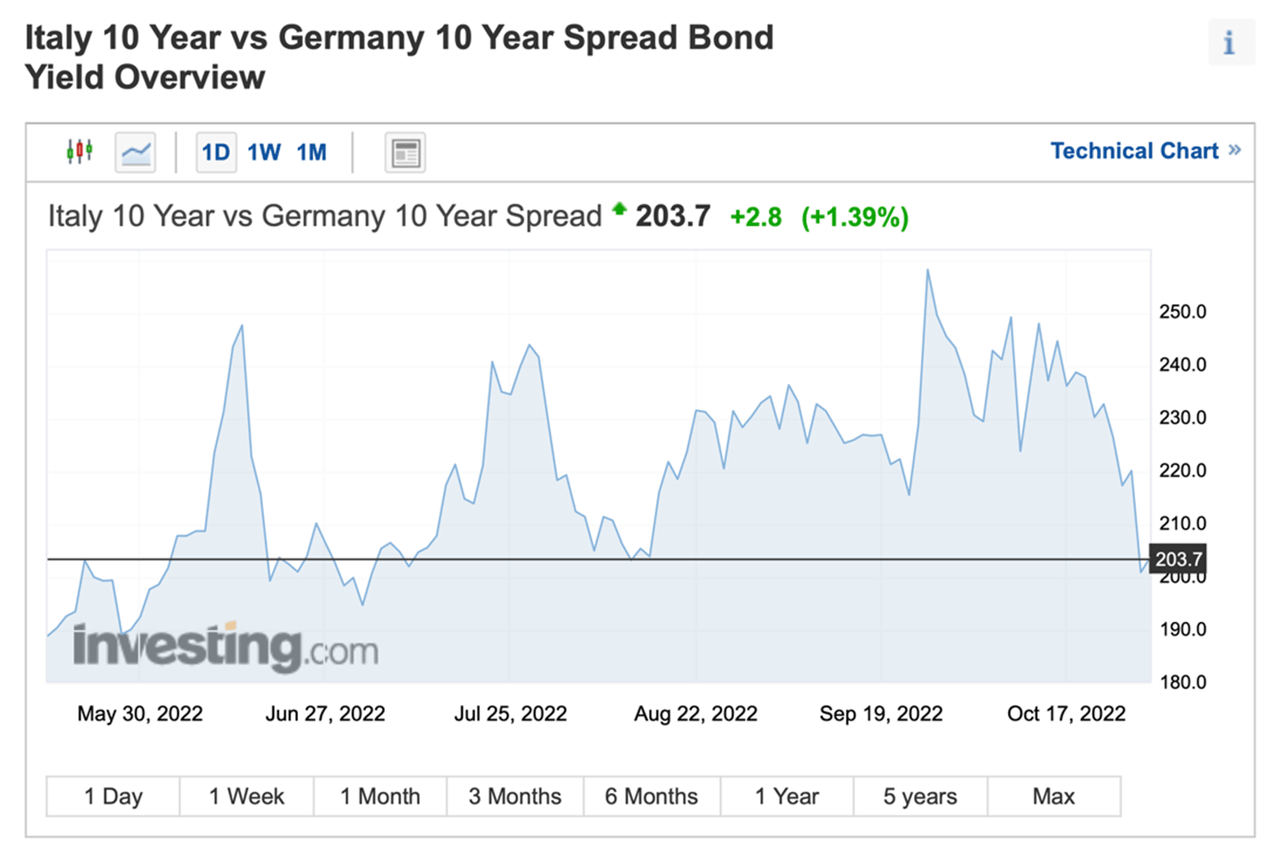

Markets know there is a contingent liability. They know that Germany is a much stronger credit than Italy is. That is why markets are pricing in a risk premium on Italian sovereign debt versus German sovereign debt.

Here’s a chart that shows the history of the interest rates on the Italian benchmark 10-year government bond versus the German 10-year government bond (BUND). Remember: This is the sovereign debt of each country and is denominated in an identical currency (euro).

(Bloomberg)

(Source)

Markets are pricing in these two sovereign debt instruments based on an unsustainability premium. Market agents know that the spread can widen for a very long time.

Markets agents also know that it will take an unexpected crisis shock to eventually change the circumstances, and that shock may be triggered by a financial accident or by the discipline of bond vigilantes.

Either way, the market agents are gradually demanding a higher and higher risk premium spread between Germany and Italy. When and where this ends is anybody’s guess.

So where the euro settles out after this recent change in ECB policy remains to be seen.

Here are the links to the two press releases and technical documents issued on October 27, describing the changes in the way the ECB offers financing to banks within the Eurozone:

“ECB recalibrates targeted lending operations to help restore price stability over the medium term” Source

“October 27, 2002, Press Conference: Christine Lagarde, President of the ECB, Luis de Guindos, Vice-President of the ECB” Source

Essentially, the ECB is finally moving away from a negative interest rate policy (a real mess in our opinion) and away from yield curve control. (That is the effective outcome of the old TLTRO structure.)

Following the announcement, the euro is worth less than a dollar on the foreign exchange markets. Meanwhile, Europe confronts Putin’s war and his threats.

Years ago, my friend Vincenzo Sciarretta and I wrote a book about the euro and Europe. Wiley liked the title Invest in Europe Now, so that was what the title became.

My friend Kathleen Stephansen wrote the chapter on integration and convergence. Vince put together interviews with major notable figures including Catherine Mann, Mark Mobius, Ed Yardeni, and Felix Zulauf.

The book took two years to write and seven months to get published after the final manuscript was submitted. Here’s the cover and link on Amazon.

(Source)

I looked at the book recently and decided to write this commentary.

What is most striking now is the possibility that the book’s title may become prescient after 15 years. Maybe, just maybe, the grand ECB experiment with negative rates and open-ended credit at a near-zero cost is coming to an end.

Of course, there is still a war going on, so we have to place an impossible-to-estimate risk premium on everything Europe while Putin’s attack on the West continues.

In my opinion, Putin’s attack is on the entire planet, because he has set back climate change mitigation for a generation while subjecting a billion people to famine and risk of death.

Some things in Europe are looking interesting and potentially attractive for the first time in a long time. We’re watching closely, as the valuations may become compelling.

Editor’s Note: The summary bullets for this article were chosen by Seeking Alpha editors.

Be the first to comment