onurdongel

Southeast Asian markets struggle to secure volumes at affordable prices

Europe’s quest for LNG to replace Russian pipeline gas will continue to prop international LNG prices until significant tranches of new supply can be brought onstream by 2025-26.

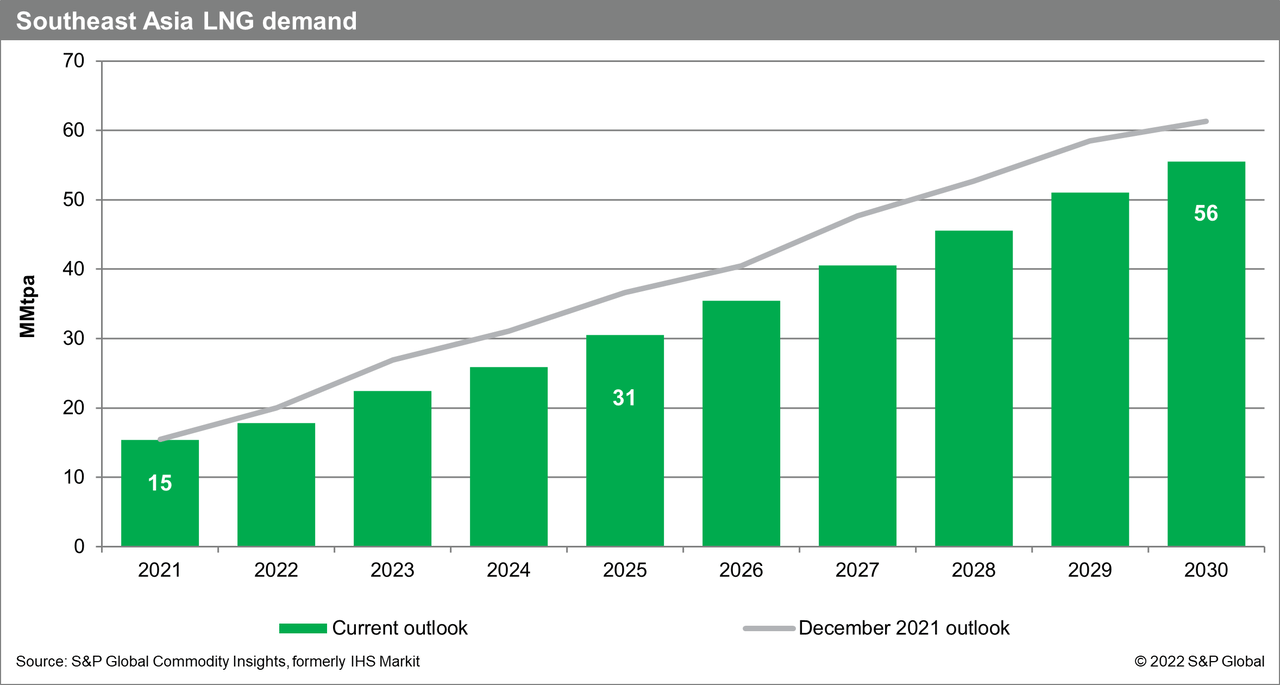

To replace sharply declining Russian piped gas supply, European gas buyers are turning to LNG and outbidding Asian buyers, driving prices higher. This competition for LNG supply is expected to sustain elevated prices in the medium term, until significant tranches of new supply can be brought onstream by 2025-26. The difficulty in securing LNG volumes at affordable prices means a slowdown in Southeast Asia’s LNG demand growth.

The price of oil-indexed LNG has increased on the back of oil prices rising to around $100/bbl, impacting existing importers. But even at this oil price level, spot LNG prices at $40-60/MMBtu are well beyond the 11%-15% slope range of oil-indexed contracts.

This price disparity incentivizes LNG sellers to continue selling on the spot market, making it difficult for buyers to sign term contracts at affordable prices. Upcoming LNG importers without any contracts such as the Philippines and Vietnam may find delaying the start of their imports more favorable if spot cargoes are too expensive.

Closing the supply gap in the short term will be difficult, and demand is likely to be lower than previously forecast. But Southeast Asia’s gas demand growth will continue. Closing the supply gap in the short term will be difficult, and demand is likely to be lower than previously forecast.

But Southeast Asia’s gas demand growth will continue. Robust electricity demand growth, coal phaseout, the investment and time needed to build out sufficient renewable capacity and grid capability all point out to an increase in gas power generation during the energy transition. In our current outlook, the region’s LNG demand would still grow from 15 MMtpa to 56 MMtpa by 2030.

Southeast Asia’s case for strong gas demand growth

In recognition of their vulnerability to the warming climate, most Southeast Asian countries have updated their climate targets in the run up to the COP26 conference in 2021, aiming for net zero between 2050 and 2065.

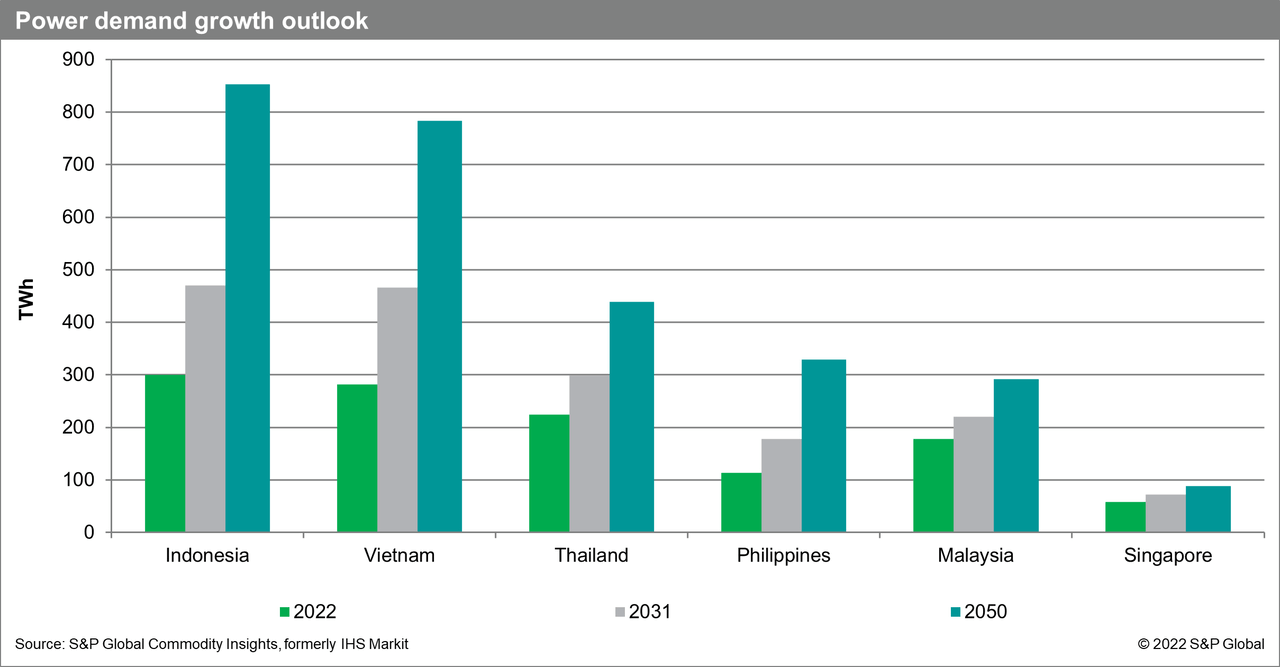

Plans to move away from coal generation has been a common feature among the region’s climate strategies, but Southeast Asia’s strong power demand growth will require adding more capacity on top of replacing coal.

In the past decade, the region’s power demand has grown 5.7% annually, more than double the global average of about 2.5%, while growth to 2031 is forecast to reach 4.5%. The options to fulfill this demand will increasingly fall on gas and renewables as financing options to build new coal plants become scarce.

High levels of renewable capacity addition are planned, with more than 50 GW of solar and wind capacity targeted to be added across Southeast Asia by 2030. To be able to handle the intermittency that comes with increased reliance on renewable generation, all countries also require hefty investments to upgrade their grid.

Vietnam has shown the issues that can happen when the development of solar and wind capacity outpaces grid enhancements. Out of 33 GW of the current solar and wind capacity in Southeast Asia, 66% of the capacity is concentrated in Vietnam.

A rush of development was triggered after the introduction of a lucrative feed-in-tariff, and more than 16 GW of solar capacity was added during 2019-20. However, the grid was not ready to integrate such influx of intermittent generation, resulting in high curtailment levels negatively impacting investors’ revenue.

It is estimated that Vietnam Electricity needs to dedicate about $3.6 billion per annum over the next five years for grid enhancements, compared to a total capital spend of $2-3 billion over the past few years.

Robust electricity demand growth, coal phaseout, along with the investment and time needed to build out sufficient renewable capacity and grid capability all point out to an increase in gas power generation during the energy transition.

An opportunity to accelerate development of domestic resources

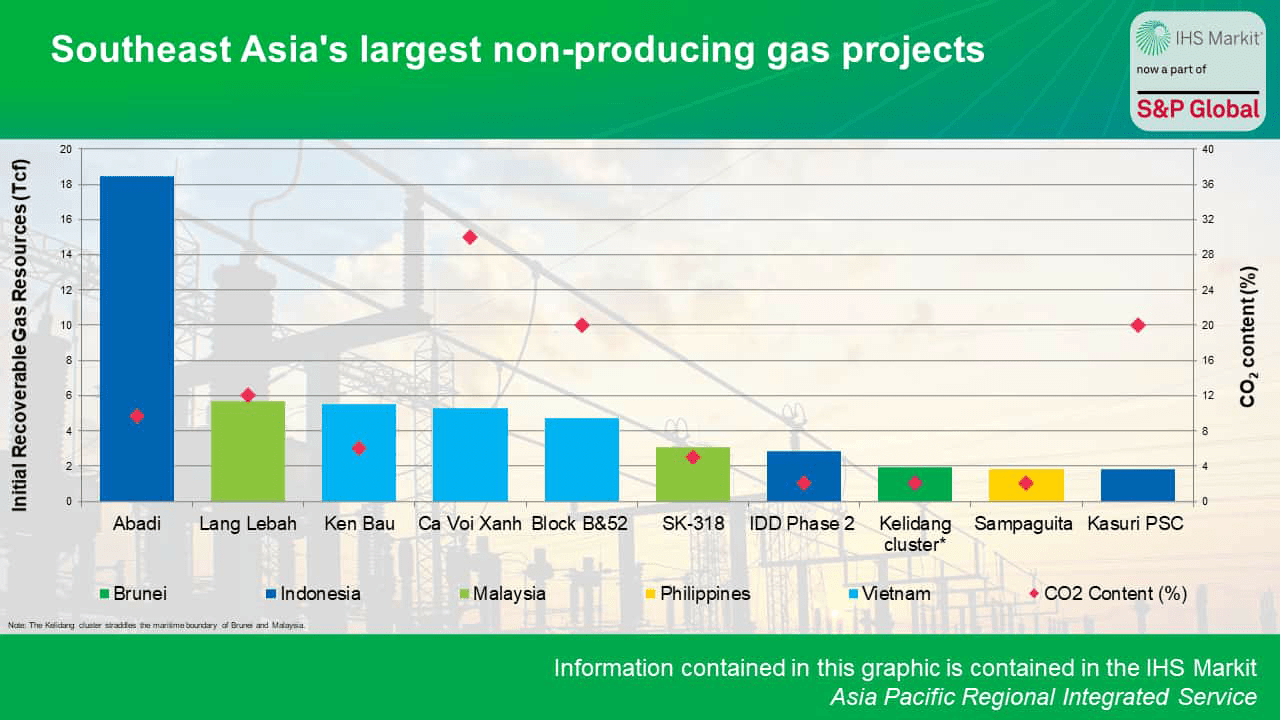

Southeast Asia still has large amounts of gas resources. The top 10 non-producing gas projects in the region have around 45 tcf of net recoverable gas between them. With 1 tcf of gas being comparable to 18 years of 1 MMtpa LNG supply, sufficient to power a 900 MW CGGT for the same period, development of these resources is critical to fuel the region’s energy transition.

Unfortunately, most of these projects have stalled. Many of the projects share similar key challenges, the first being high CO2 and the additional cost of handling it. The only two projects in the chart above that are seeing clear progress are in Malaysia, despite having fields with relatively high CO2.

This is because PETRONAS has realized that development of its large gas fields with high contaminants is crucial to maintain the utilization of its key asset, Malaysia LNG (MLNG), and it is working with its partners to fast-track CCS infrastructure using depleted fields as storage. Work on Malaysia’s regulatory and incentives framework to support these CCS developments is also ongoing.

The second key challenge facing upstream development is a lack of market or difficulty in finalizing offtake agreements. For example, both Cai Voi Xanh and Ken Bau are in the central coast of Vietnam, while Vietnam’s gas market is concentrated in the south.

With no gas market nearby, these projects need to be developed with an integrated power development but are faced with difficulty in securing PPAs and a public-private partnership regulation that is less friendly to international investments.

The third key challenge is international players exiting the region. Shell (SHEL), Chevron (CVX), and Murphy (MUR) are seeking to exit from their positions in Abadi, IDD, and the Kelidang cluster, respectively.

Although the underlying factors are not the same, these projects share a lack of robustness that made them prone to substantial delays and struggle against more promising projects in a global upstream portfolio.

Addressing these challenges are not easy but lowering the barriers for the projects can be achieved if governments choose to adapt their policies. For instance, adjusting domestic gas price expectations, providing incentives, and implementing carbon pricing can help accommodate CCS costs.

The ability to limit the carbon intensity of upstream developments can be especially attractive and it is evolving to be a key requirement for many international players.

These changes are already taking place. As spot LNG prices continue to stay high and long-term contracts are difficult to secure, markets will look for alternatives.

The development of a shared carbon capture facility and the regulatory framework supporting CCS in Malaysia may be replicated across the region that will allow more upstream investments to take place.

The increase in dialogue between governments to reach a consensus on shared resources, such as between Thailand and Cambodia, is another signal that changes are afoot.

Editor’s Note: The summary bullets for this article were chosen by Seeking Alpha editors.

Be the first to comment