Rowan Jordan/iStock via Getty Images

Managed Distribution Policies: How They Work

Most investors in closed-end funds are primarily interested in current income. That is certainly a big reason I utilize them so extensively in my Income Factory® portfolios, given our interest in achieving equity returns of 9-10%, but preferring to get that return mostly in cash distributions rather than having to “wait and hope” for the market to give it to us in capital gains.

Closed-end funds, knowing there are plenty of investors like us around (whether we call ourselves “Income Factory” investors or just plain old income investors), often tailor their distribution policies to suit what they perceive to be their clients’ (i.e. potential investors’) needs and desires. In other words, many of them try to find a way to pay out as much as possible of their total return in the form of cash distributions, since they know how popular high yields are with many retail investors.

All of this is fine (and indeed, helps to serve our purposes as Income Factory investors) as long as a fund doesn’t become overly exuberant and get into the habit of paying out a larger distribution than it actually earns. We have written in the past (link here) about funds that pay out “feel good” yields that exceed their actual total returns and end up eroding the shareholders’ capital over time.

Earning A Fund’s Distribution; What Does That Mean?

Funds produce income (i.e. “total return”) for their shareholders in two ways: (1) paying them cash as dividends or distributions, and (2) appreciating in price and/or net asset value.

Note: Since closed-end funds are sold on the market like stocks, their market price can and usually does diverge from their underlying net asset value, or “NAV,” which is the sum of the market prices of all the assets the fund holds, minus any debt if its leveraged, divided by the number of fund shares. That means a fund can appreciate or depreciate in value in two ways. One in terms of its market value, and the other in terms of its NAV. We therefore end up reporting two total return statistics for closed-end funds, one showing the gain or loss in its market price, and the other showing the gain or loss in its NAV, each one, of course, added to the amount of the cash distributions for that reporting period.

Over time, we want a fund’s total return to exceed, or at least equal, the amount of the distributions it pays out. If it doesn’t, and the distribution exceeds the total return, that means the value of the fund’s shares, measured as market value or NAV, must have fallen. That’s a mathematical certainty. Since total return equals distributions plus gains or losses, if the distribution is MORE than the total return, then the gain or loss MUST be negative to make up the difference.

Some funds are what I call “serial eroders” of shareholder capital, since they consistently, over many years, pay out more in distributions than they earn in total return. One of these is MFS Intermediate Income Trust (MIN), which pays out a distribution which, despite its steady decrease over the years, still currently represents an overly generous 9% yield, even though the fund’s annualized return over the past 10 years has been less than 2%. You can’t pay out 9% while only earning 2% for very long without eroding your capital and turning yourself into an “annuity,” which is essentially what MIN has been doing. (Read more about it here). Another good example of a serial eroder is Franklin Limited Duration Income (FTF), which pays out over 10% in yield while having made less than 3% annualized for the past 10 years (link here).

Managed Distributions Are Different, At Least In Theory

Managed distributions are usually implemented by funds that DO earn their distribution over time. But they don’t always earn it steadily and consistently, month to month.

In most cases, it is more likely to be an equity fund than a credit fund. Equity investments, especially growth stocks, generally pay small dividend yields of perhaps 1 to 3%, and expect to achieve an average appreciation in their stock price of another 6 or 8% (or even more) to meet the total return target of 9 or 10% that equity investments have delivered on average over the past century or so.

Successful closed-end equity funds know that many of their investors are looking for consistent income. The funds also know that, even if they are successful at achieving the market gains required to meet their return targets, that it will likely be “lumpy” and not smooth. There will be some periods that are flat, and the fund’s only income may be from its portfolio’s tiny 1 to 3% dividend stream. In other periods they may have gains that raise their total return above the 9-10% average, and in others they may suffer losses.

With a “managed distribution,” a fund selects an average distribution that it believes it can sustain based on its average performance over time, and then pays out its distribution at that rate, month after month, or quarter after quarter, whether it actually earns it during that period or not. If a fund pays, for example, a 7% per annum distribution, it may own stocks paying it an average dividend of 2% and be relying on a minimum average gain each month at a 5% annualized rate in order to make up the difference and support that distribution.

Some months it may make twice the capital gains it needs to support the payout; while in other months it may make zero, or even suffer losses. Managed distributions smooth out these ups and downs by allowing fund managers to spread out their gains and losses, essentially “borrowing” from expected future gains in order to pay today’s distribution even if there weren’t sufficient gains this period to do so.

“Managing” Through Extended Downturns

The challenge with managed distributions is what happens if the “down periods” stretch beyond just a month or so and turn into a bear market or equivalent. Instead of merely borrowing from next month or next quarter’s anticipated gains, managed distributions through an extended downturn can mean borrowing expected or hoped for gains from a year or so in the future.

The funds being “borrowed” to pay us our distribution come from the fund’s existing capital base, so paying us a distribution that hasn’t been earned yet means it is essentially “selling at the bottom,” liquidating existing assets and turning paper losses into real ones; thus reducing the capital the fund has invested that can benefit from the recovery when it comes.

This is not a problem for investors who reinvest and compound the distributions, therefore maintaining their capital base intact so they’ll get the benefit of an upturn, when it comes. But retirees and others who need the income, and therefore keep and spend, rather than reinvesting and compounding, their current distributions, should understand the payouts they are keeping are eroding their fund’s capital base (essentially “eating their seed corn”).

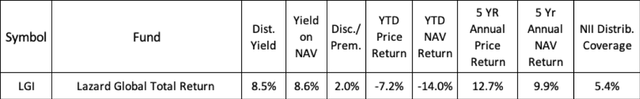

This is not to beat up on solid equity funds with great long-term records. One of my favorites, Lazard Global Total Return (LGI), is a good example of a fund I have no problems owning and holding through this downturn, knowing it will come back and be successful over the long term. But I am being careful to reinvest its managed distribution (which is currently almost 9%, given LGI’s depressed price, having been set at 7% of its then-current NAV at the start of this year) so as not to erode the capital I actually have invested in the fund.

SB

Note how long term LGI has indeed supported its distribution with its total return, so this is NOT an example of a “serial eroder” as described earlier. But notice the 5.4% NII distribution coverage ratio. This is typical of equity funds, even very successful ones, that earn very little of their return from dividends, and most of it from capital gains; of which, we can see in the “year-to-date” columns, there obviously have been very few lately. So investors in LGI, who want to fully participate in an eventual comeback in the fund’s stock price, would be wise to continue reinvesting through the downturn.

The Solution for Income Investors

Investors who need to use and spend their distributions, and are not in a position to reinvest them, can still ensure that the cash they receive is NOT coming out of their fund’s capital. The secret is to invest in funds that receive the bulk of their own income in the form of cash interest and dividends, and then use that cash to fund the dividends they pay to their investors.

The way I do that is by focusing on credit funds and other fixed income funds whose payouts are covered by Net Investment Income. That way they are paying me my distribution with cash received from the regular dividend and interest payments they receive from their portfolio investments, without having to liquidate any of those investments to do so. Thus they keep their capital intact and fully available to both (1) continue paying their existing distributions and (2) rise in value when the market finally picks up.

In the meantime, if I am an income investor who needs to spend the income, I can do so knowing that my fund is not selling off any capital, and therefore not reducing its ability to continue pumping out my distributions.

And if I’m able to reinvest some or all of my distributions, I have the additional satisfaction of knowing I’m “giving myself a raise” every month by reinvesting and compounding at bargain prices and yields that are higher than ever as the market prices have dropped. Again without tapping any of the fund’s capital, so it is fully poised to take advantage of the market rise when it finally comes.

Bottom Line

I have written extensively about how “credit bets” are easier to win than “equity bets” because all the company has to do is stay alive and pay its debts, even if its stock tanks. (i.e. like betting on a horse to merely “finish the race” as opposed to betting on one to “win, place or show.”)

But at times like this, when the market has been so turbulent for so long, and looks like it could continue to be for a while longer, the credit bet has the additional advantage of allowing us to collect and keep some or all of our distributions, knowing that it has actually been earned and doesn’t represent an erosion of capital that we will regret no longer having invested in the fund, when the upturn finally arrives.

Examples of credit funds or firms whose NII’s fully cover their distributions, and are therefore not depleting their capital in making their generous payouts while we await a price recovery, are:

- KKR Income Opportunities (KIO)

- Oxford Lane Capital (OXLC)

- Barings Global Short Duration (BGH)

- Ares Dynamic Credit Allocation (ARDC)

- XAI Octagon Floating Rate & Alternative Income (XFLT)

I hope this is useful and look forward to your comments and questions.

Be the first to comment