Vertigo3d/E+ via Getty Images

by Monia Magnani and Massimo Guidolin

The pandemic has placed fintech’s adoption into overdrive, with digital payments being enjoying mass diffusion. It is a commonly shared view that the key avenues of future growth in fintech include “buy now, pay later” (BNPL), cloud banking, and blockchain-based segments. However, recently, there has been much angst concerning the fact that the resurgence of inflation may hurt or benefit the development of fintech firms and hence deflate or provide further support to the valuations of the key players in the sector. As almost always in life as well as in financial valuation matters, a number of macroeconomic arguments lead us to conclude that the complexity and fragmentation of the fintech sector—both in terms of geography and business—coupled with the heterogeneity in the drivers of the recent inflation urge, make a simple answer impossible. However, the nuisances in this very failure to find a simplistic argument, suggest the potential for sources of both creation and loss of value that may be tradeable.

Massive heterogeneity in inflationary pressures and in the fintech landscape

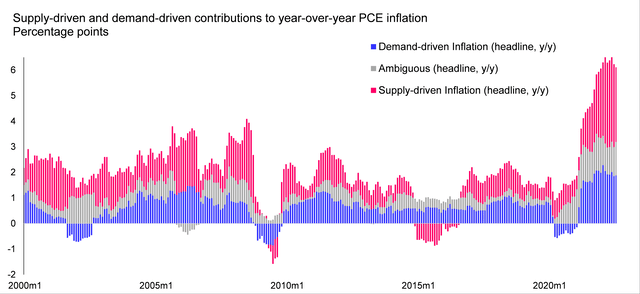

One fact occasionally overlooked in commentaries of recent macroeconomic developments and yet increasingly researched by professional economists is the fact that the current inflationary surge seems to be driven both by supply and by demand factors. This is different from other well-known episodes of inflation spikes, such as the predominantly supply-, international conflict-driven surge in prices recorded in the mid-1970s and again in the early 1980s; or the bubbling, exuberant demand-driven inflation recorded in 2006-2007. Data from 2022 show in a persuasive manner that, at least in the United States, both supply- and demand-driven factors are simultaneously at work in pushing general price indices up. Moreover, such factors carry a different weight over time even within the same country (see, e.g., Figure 1 below, showing a rather different characterization of the PCE drivers for 2021 vs. 2022 in the US) and are heterogeneous in the cross-section of different countries. For instance, a consensus is emerging of a stronger contribution of energy-related inflationary pressures in Europe vs. the United States. This derives from the fact that many European countries depend on energy imports on a large extent, while the US have turned into a net energy exporter since 2019.

Figure 1: Supply-driven and demand-driven contributions to year-over-year headline PCE inflation (elaborations by the Authors on data made available by the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco at https://www.frbsf.org/economic-research/indicators-data/supply-and-demand-driven-pce-inflation/)

Figure 1 uses a recent decomposition of PCE inflation based on a model of supply vs. demand shocks made available by researchers at the Federal Reserve (see, e.g., here also for a precise account of their methodology). Year-over-year headline PCE (Personal Consumption Expenditure) inflation consists of the rate of growth between a given month of year t – 1 and the same of month of year t in the index that reflects the prices of goods and services (including food and energy) purchased by consumers in the US. The demand-driven component includes the effect of the pent-up demand that has cumulated during the Covid-related lock-downs and more generally the ensuing slowdown both in the general growth of disposable incomes and in the chances to consume some types of goods and services, such as restaurant meals, vacations, travel, etc. The supply-side contribution to the inflation burst derives instead from:

- the labor shortages and other increases in operating outlays due to Covid-19 (e.g., the effects of the “Great Resignation”, see J. Blum’s article here, and the surge in the costs of offering personal services, for instance, restaurants and entertainment);

- the supply shortages caused by difficulties in worldwide shipments and supply chains;

- the recent, massive increase in energy input prices and in the price of other imports—raw materials and commodities, intermediate goods, as well as final consumption goods—also triggered by the invasion of Ukraine and the resulting international tensions.

The plot shows that, even though during 2022 the contribution of demand-driven PCE inflation has been positive, as a fraction of the total it has also been declining and it is now overshadowed by the contribution given by the supply-side factors. As recently acknowledged by the Fed‘s Chair Powell, policymakers cannot really control supply.

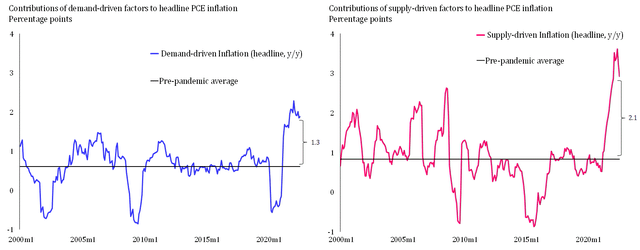

Figure 2 further details the fact that although the contribution to PCE inflation of supply-driven factors has been increasing from essentially zero in 2020 to more than 3% in mid-2022, the demand-driven inflation—markedly, the pent-up demand generated by the Covid-19 hardships subsequently freed up by the American Rescue Plan enacted in March 2021 —has been exceeding 1% per year since early 2021, recently spiking up to exceed 2%.

Figure 2: Contributions of supply- and demand-driven factors to year-over-year headline PCE inflation (elaborations by the Authors on data made available by the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco)

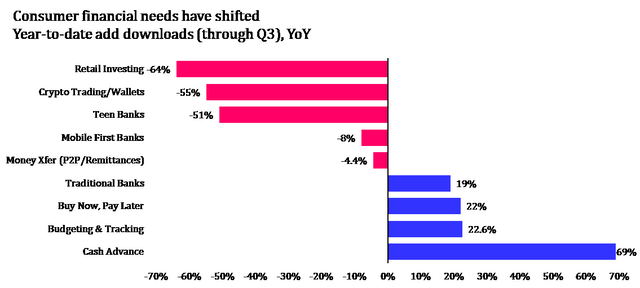

The landscape and evolution of the fintech sector is however as heterogeneous as the inflation drivers. Figure 3 documents the rate of growth of app downloads (through Q3 of 2022) for a range of fintech sub-sectors, as sampled and reported by Apptopia. Although not without problems, app downloads seem to be highly representative of the size and speed of expansion of the fintech phenomenon.

Figure 3: Changes in the fintech-related financial needs as measured by the rate of growth in the number of downloaded applications on personal communication devices (elaborations by the Authors on data made available at https://apptopia.com/)

Not only the fintech sub-sectors are many and varied in terms of business contents and demand needs catered to, ranging from retail investing, mobile banks, P2P remittance services, budgeting and tracking to cash in advance credit (BNPL, that we also call neo-banks) facilities and crypto-trading wallets. In addition, at least between 2021 and 2022, these heterogeneous incarnations of fintech have grown, when they have not deflated, at bewildering different annual rates, ranging from -64% for retail investing and -55% for crypto trading apps, in contrast to the persistently solid growth of budgeting and tracking and of loan apps (+22.6%), to the recently explosive growth of apps that allow consumers to tap cash from advance facilities. It seems that while inflation and more generally, the evolution of the economic environment that has taken place between 2020 and 2022, have favored some fintech applications, other sub-sectors appear to be suffering and even losing ground, in relative terms.

Why and how can an inflationary surge hurt fintech

In a high inflation environment, all financial firms—and especially those in the fintech industry—face a declining operational efficiency caused by an increased number of vulnerable customers that need to be managed. Many fintech firms have increasingly focused on serving less affluent consumers bypassed by traditional institutions, for instance those in the BNPL and cash-in-advance business. The fintech firms with higher exposure to these groups are likely to suffer a greater impact if the economy deteriorates because of the compression in disposable incomes caused by supply-driven inflationary pressures (in particular, by high energy costs). For instance, cash-in-advance and BNPL companies are sitting on a growing fraction of sub-prime clients.

Moreover, the so-called neo-banking industry—fintech firms specializing in tech platform-assisted small loans—was born in a low-interest environment and has focused on innovative benefits and low- or no-fee services to attract customers; few offer interest-bearing accounts. If high interest paying deposit accounts were to become the standard in the coming years, as we are increasingly reading in the news, this would have a major impact because if a neo-bank cannot offer the best interest rates, it will better offer terrific service features, else producing net positive operative margins quickly becomes problematic. Therefore, supply-driven inflation, especially by impairing the spending power of low-income, low-wealth customers represent an imminent risk to the profitability of large segments of fintech (that Figure 3 shows are suffering already) and will put them under pressure to raise the quality and effectiveness of their services. Rising nominal interest rates resulting from higher inflation could also alter the relationship between neo-banks and the chartered, partner banks that provide them with auxiliary banking services (e.g., payments and collection), raising costs and further shrinking the margins.

While it is doubtful that supply-side and energy-cost related inflation may provide a boost to any of the fintech subsectors in Figure 3, it is prudent to estimate that the business of retail investing and mobile bank apps will be damaged only assuming that a downturn caused by inflation may affect the financial markets to the point to discourage trading and payments executed by retail investors and households. On the basis of the data in Figure 3, this seems under way. A different and separate issue concerns the likely evolutions of crypto trading and wallets, which appear more related to the outlook of cryptocurrencies as an asset class and not discussed further here.

In any event, several fintech companies have been forced to cut staff, citing inflation as a cause. In September 2022, there was considerable echo from Robinhood’s (NASDAQ: HOOD) decision to cut 23% of its staff and Klarna’s (still private) similar announcement, affecting 10% of staff. It is also a widely reported circumstance that the unfolding economic conditions make it difficult for fintech firms to attract investors and additional capital. Shares in recently listed fintech firms have fallen an average of more than 50%since the start of the year, compared with a 31% drop in the Nasdaq Composite as of the end of September 2022. According to KPMG’s Pulse, total fintech investment fell from $111.2 billion in an extraordinary 2021 H2 to $107.8 billion in 2022 H1with reference to worldwide venture capital flows. Interestingly, the sudden slowdown in the expansion of the fintech sector is a predominantly US phenomenon. Bloomberg Law’s data show that during the same time span, the Asia-Pacific region saw total fintech investment more than double from $19.2 billion in 2021 H2 to a record $41.8 billion in 2022 H1.Meanwhile, the Americas and EMEA regions (i.e., Europe, Middle East and Africa) have seen a decline in investment in fintech from $ 59.7 billion to $ 39.4 billion and from $ 31.6 billion to $ 26.6 billion, respectively.

Why and how can an inflationary surge benefit fintech

While it is hard to imagine why and how supply-driven inflation may benefit fintech companies, there are reasons to think that demand-push inflation, stemming from pent-up demand that had cumulated because of the Covid-19 restrictions, may represent an asset to a few, specific types of fintech businesses. First, demand-driven inflation may be good for payment processors because this increases overall nominal volumes and hence fees when these are proportional to volumes. Recently, the stocks of payment processors (both legacy players such as Visa (NYSE: V) (see the analysis by M. Schiavo here) and American Express (NYSE: AXP), and new entrants like Block (NYSE: SQ) and PayPal (NASDAQ: PYPL)) have been voiced to even represent effective inflation hedges (see e.g., the analysis here with reference to Ark ETF (NYSEARCA: ARKF)). However, it must be recognized that down the road, payment processors will not be immune to the expense push of inflation, particularly as it relates to staff outlays. Yet, the latter once more represent an example of a supply-side inflation driver, associated with the recent scarcity of labor. Moreover, an unconditional, positive assessment of the outlook of payment processors is subject to important caveats as, on their revenue side, fee-based and transactional pricing do not display the automatically adjusting quality of ad valorem pricing, as dollar volumes rise due to inflation.

Another type of fintech firms that may end up profiting from demand-side inflation pressures include fintech companies that are active in the small-scale lending business. Since household budgets are getting tighter because of the inflation pressures but consumption demand has stayed so far relatively strong and the occupational perspectives appear to be at an all-time high, BNPL fintech products (e.g., Sofi, NASDAQ: SOFI) may gain business and depth of their customer base. This seems likely to last as long as high inflation refrains from degenerating into a full-blown stagflation trap. Yet, also in the case of credit and cash in advance business, these may be later hit by higher real interest rates as some merchants may consider stopping the related services.

Finally, fintech catering to the borrowing needs of small and medium firms (e.g., equity crowdfunding and P2P lending) may also fare well in the short-run, but eventually what matters is again whether the recent inflation spike will settle in generating stagflation. A cautious view should take into careful account the real economy, potential recessionary aspects, relative to any alleged benefit deriving from higher nominal prices.

Of virtuous cycles: why should policymakers support fintech in the face of heightened inflation

As it is well known from textbook macroeconomics, the dominant component of the welfare costs of inflation—the measurable reduction in the well-being experienced by individuals—is induced by the distortions related to the management of cash balances for transaction purposes when a (nominal) interest-bearing asset is available. In essence, because holding cash not invested in interest-bearing assets is as at least as expensive as the inflation rate, as the latter grows, the individuals would spend real resources in frequent trips to withdraw (in modern times, cumulate liquid balances) cash of relatively small amounts. Since the late 1980s, economists have empirically estimated massive welfare costs of a permanent inflation surge, in the order of more than 1% per year of lost output (see, e.g., Dotsey and Ireland’s seminal paper here). Moreover, such losses would be distributed in rather asymmetric ways, for instance with the youngest households to gain in net terms because high inflation tends to reduce the real burden of their mortgages; on the contrary, the poorest elders would bear the highest damage from inflation because of their assets and pensions that tend to be fixed in nominal terms.

The economics literature is practically unanimous in reporting that all kinds of financial innovation—in modern times, this is chiefly represented by fintech—considerably reduce the welfare costs of inflation. Rather intuitively, this occurs because fintech applications tend to make the management of cash balances efficient and automatic, thus saving the individuals the costs of its management and minimizing the mistakes from its discretionary handling. Moreover, many fintech applications would easily integrate the remuneration of cash balances, effectively cutting the need for obsessive cash balance control. Some papers, both recent and less recent, propose empirical estimates by which the welfare costs of inflation are almost halved by financial innovation (see, e.g., recent work by Cao et al. here). Therefore, if an inflation spike is due to cause massive welfare costs but these are tamed when/where financial innovation is stronger, there should be outright public support to fintech. In the measure in which such a public support were to find its way among the priorities of policymakers, this suggests that policy initiatives to strengthen fintech and make it safe and hence trustable to the public may eventually counteract the headwinds that fintech is about to face. As hard to predict as it may be, this endogenous force may need to be factored in when we think of how fintech will be affected by renewed and persistent inflation.

Conclusions

When we try to forecast the interaction of two heterogeneous phenomena such as the recent inflation surge (because it is driven by both demand and supply factors) and fintech (in its numerous facets and business characterizations), it is hard to derive any unequivocal indications. There are reasons to think that supply-driven inflation will hurt, especially if it will cause a recession, many fintech firms; however, the demand-driven inflation factors may be exploitable by some specific fintech sub-sectors. Policymakers worldwide are dealing with immense pressures to act swiftly and to minimize any policy mistakes and yet finding some space to support and regulate fintech (for instance to reduce impact and spread of scams and theft in the cryptocurrency space, see, e.g., the 2022 Chainalysis’s report here) would be not only justified in view of a goal to reduce the welfare costs of inflation, but also extremely timely.

These arguments lead us to conclude that investors with a strong risk appetite should look for bargains among the individual fintech stocks (such as those listed above) when they are not exposed to supply-driven inflation. More generally however, the remaining investors should be wary of expanding sizeable positions in fintech (e.g., through ETF vehicles) as their medium-term performance will depend on the persistence of the supply-driven inflation component.

Be the first to comment