NoDerog/iStock Unreleased via Getty Images

In 1972 and with the beginning of détente, Pepsi (NASDAQ:PEP) became “the first capitalistic brand produced in the Soviet Union”. Coca-Cola (NYSE:KO) followed in 1979 when it began selling Fanta in select cities. The opening of China was not far behind, except this time it was Coke who was in the lead (returning after having exited China for “historical reasons” in 1946). In each case, it was political connections between the soda CEOs of the time and their American presidential counterparts (Pepsi seemingly have been closer to Republicans and Coca-Cola Democrats) that allegedly proved decisive in getting their respective feet in the communists’ respective doors. Since then, the victory of mass consumerism, capitalism, liberalization, globalization, and American hegemony have proved a heady mix for the soda giants. Many of these forces seem increasingly to be on the wane, however, and the unravelling of the post-Cold War order is, almost day by day, palpable.

In Xinjiang, Tibet, and Hong Kong, along the Chinese borders with India and Bhutan and in the South China Sea, and the growing threat to Taiwan. To the west, in what is looking increasingly like a European civil war without end centered on Ukraine. And, in the rise of populism even in the American core and the subsequent failure of the establishment to produce viable presidential candidates that are not more than double the minimum age threshold to hold office. Parallel to this are changing consumer tastes and mores, which the soda (and snack) giants are trying to both mitigate and exploit. Take, for example, the focus of these multinational corporations on environmental, social, and governmental (ESG) responsibilities which attempts to satisfy the demands of growing numbers of consumers and investors and the attempt to move beyond staid and sugary sodas. Notice that focusing on ESG responsibilities is a relatively cheap alternative to finding a business model not based on hooking consumers on an early diet of sugar and a lifelong diet of insulin injections (especially among both the poor and people of color).

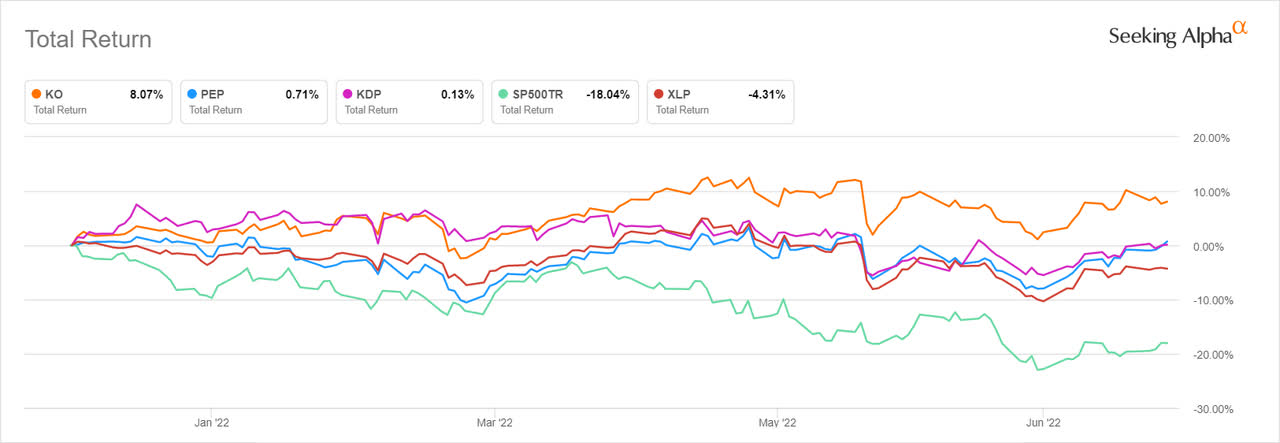

Judging from prices for Coca-Cola, PepsiCo, and Keurig Dr Pepper (KDP) shares-at 27, 23, and 22 times earnings, respectively- this is an exaggeration of the long-term macro challenges described above. Not only are they at historically high levels but the multiples are, relative to one another, nearly inverse the magnitude of the challenges described above. In other words, even though Coke is at greatest risk from these challenges and KDP is at least risk, the former is priced highest and the latter lowest on this (admittedly over-simplified) measure. There are some good short-term reasons for this inversion. These headwinds are long-term concerns; over the short-term, where the threats of high inflation and/or cyclical growth shocks appear to be most pressing, KO and PEP are likely to produce more sustained revenues and profits and continue to fill their role as defensive redoubts for investors. Even here, though, we may have seen this short-term relative performance itself somewhat overdone, and a bear market rally in ostensibly riskier assets or, alternatively, further broad downward pressure could force these stocks to see more red than they had seen when they first ventured beyond the Iron Curtain.

Chart A. Coke has showed its staying power thus far. (Seeking Alpha)

Since we are talking about both long-term and short-term returns and both absolute and relative returns (these stocks relative to one another and relative to the broader market), it is easy to get confused, so let me try to be explicit.

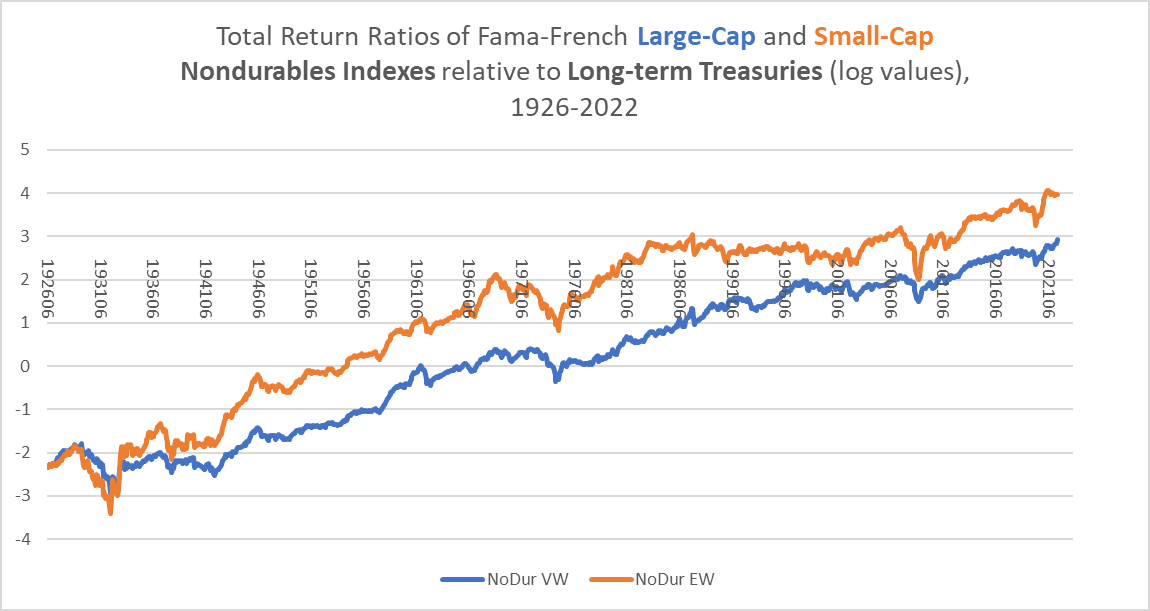

Large-cap staples have a well-deserved reputation for outperforming the broader market during cyclical downturns. As I demonstrated in my recent write-up of the Consumer Staples ETF (XLP), historically, stocks in the nondurable consumer goods space have also tended to do very well, relative to an equal-weighted sector index, during a secular underperformance of the tech sector. The tech sector tends to underperform when a number of conditions manifest themselves. Briefly, those are a) after extended periods of tech outperformance, b) after extended periods of energy sector underperformance, c) after periods of abnormally high PE valuations across the market, and d) after a cyclical commodity/energy shock. I have described this in a number of articles about the tech-heavy sectors.

These are not the only conditions in which tech can underperform, but in the brief historical record available to us (back to 1926, thanks to Fama and French), when the conditions just described have presented themselves, relative long-term tech underperformance has followed. Unfortunately, in these situations, these periods of relative tech underperformance have also coincided with periods of absolute bearishness for the market as a whole. Relative sectoral performances are, in other words, often connected to absolute performance.

Depending on one’s perspective, this macro outlook either informs or biases my perspective of the soda giants. All else being equal, I expect all sectors to see flat to negative long-term (end of decade) returns, negative cyclical (two years) returns, and consumer staples outperformance over both cyclical and long-term durations. I also expect large-cap staples to continue outperforming small-cap staples during most of the remainder of the cyclical downturn, although I expect small-cap staples will outperform over the long term. History suggests that the most important question under these circumstances is whether the long-term is going to be primarily inflationary (as in the 1970s and 2000s) or deflationary (as in the 1930s). If it is the former, returns in staples will likely be volatile but relatively flat; if it is the latter, returns will likely be volatile and negative.

Let me add another macro layer here. In a recent series about the relationship between technology, war, and asset prices, I retooled Schumpeter’s innovation theory and Kondratiev’s closely related theories and observations on capitalist development to try to anticipate certain long-term trends. Historically, after the peak of one of these tech-dominated booms (both in terms of market performance and on-the-ground dynamics), the world has experienced, in addition to the lower overall returns described above, both rising innovation (somewhat counterintuitively), and palpable global instability typically accompanied by what might be called “system wars” or wars at the hegemonic levels. Unexpectedly, both real commodity prices and the earnings yield (the inverse of the PE ratio) on the S&P Composite going back over a century and a half have been correlated with global deaths in conflicts.

Earlier in the year, in a series called ‘The Death of Irrational Exuberance’, I argued that, for whatever reasons-probably linked to the overwhelming Cold War victory of the United States and NATO and the successful integration of relatively cheap labor into the global capitalist system-the earnings yield and real commodity prices were likely being held below what appears to be a long-term equilibrium level. This has coincided with relative global stability, i.e., a relatively weak “war cycle”. If the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan were a political, fiscal, and humanitarian disaster, they were not as severe as the disruptions of the Cold War conflicts in the 1960s and 1970s or the World Wars. In other words, the last forty years have seen both much higher stock returns and a much greater degree of global integration than is normal. This has likely contributed to a North Atlantic conviction that the end of history has arrived and that the world is destined to look something like the European Union, even as the EU has struggled to maintain its own coherence.

On a deeper, structural level, globalization has been driven by the American need to relieve itself of a dollar-driven and, thus, self-imposed “cost disease”. This dynamic, first outlined by William Baumol in the 1960s to describe the decay of American inner cities, is driven by goosed durable goods sector productivity in turn forcing up the cost of labor. Labor-intensive (and thus low-productivity) industries (especially health care and education) have little choice but to raise their prices in response, but capital-intensive industries can offshore production or bring in immigrant labor to preserve profit growth. Since World War II, therefore, we have seen global production outsourced, in successive “miraculous” waves, to post-War Europe, then Japan, East and Southeast Asia, and ultimately former Warsaw Pact economies and, most famously, China. Even before that, however, the US saw the same process occur domestically, as production shifted both away from urban cores and the Northeast while simultaneously drawing in labor from historically peripheral or marginalized sources (women, blacks, immigrants) and creating one of the greatest cities of the world in its time.

Once this process is completed, however, the industry that it helped throw up (in 1920s’ Detroit, the auto industry) chokes on its own success. The industry is mature, and labor and property prices sit atop a permanently high plateau. It is often said by naïve free-marketers that “high prices are the cure for high prices”, but this is not true in a monetary system that is geared towards goosing mass production and consumption. Cities and regions in wealthy countries will rot and die before they reprice to become competitive with the countries and immigrant labor that “steal” their jobs. Because they rise so quickly and inorganically, once the industrial boom passes, there is nothing left to prop up that local economy. As Baumol described with reference to inner cities in the 1960s, this dynamic has gripped much of Rust Belt America with similar social and political dysfunction. All that is left is populist fury and technocratic tut-tutting.

The exhaustion of democratic capitalism

“When Alexander saw the breadth of his domain, he wept for there were no more worlds to conquer.” There is little space left for these forces of globalization to work their magical cures. Generally, these waves of development occur in areas that are typically operating under an already clearly defined long-term potential. Either these areas were recently colonized by otherwise developed countries (for example, the internal frontier outside of the American Northeast) or they are countries with historically high levels of development that appear to have sunk below their historical level. As Jane Jacobs pointed out, this was a big part of the reason the Marshall Plan worked so well in post-War Europe and why it works so poorly in places like Afghanistan. Countries that have long traditions of “high” civilization or who have been colonized by such countries have had a significantly easier time of moving up the development ladder.

By these standards, there are relatively few places for the road of cheap globalization to run. This is not to say that the globe has inevitably come to the end of economic development but rather that these particular modes and these particular waves look spent. Very long term, there are likely to be opportunities located around the Indian Ocean, in particular from Indonesia to South Asia to Africa, but at the moment, the world as a whole does not seem to be in great of significantly new capacities for cheap gadget production. Rather, the world has to wait with bated breath to see how the increasingly acrimonious competition between China and the US will turn out. To judge by the events in Ukraine, it is the US and its allies that are in the weaker position.

Certainly Coca-Cola and PepsiCo are weaker for it. Things have changed.

The Moscow Olympics of 1980 presented Coca-Cola with a golden opportunity. Although the U.S. declared a boycott of the games following the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, Coke ignored it, pointing to the fact that it had been sponsor and partner of the Olympics since 1928. As a multinational company it was above politics, it added. Thus Coca-Cola became the main drink of the Moscow Games.

So says Russia Beyond in “How PepsiCo and Coca-Cola clashed for control of the Soviet Union” (see link in first paragraph). This time, of course, there has been immense pressure to pull out of Russia. As far as I am aware, PepsiCo has now confined itself to selling things like baby formula there while Coca-Cola has pulled out altogether and has been replaced by Cool Cola, Fancy, and Street.

For better or worse, the world is deglobalizing wholesale, and the soda giants are at (or near) the front of this process. Perhaps they have been pushed to the front by consumers and politicians in their core markets, but that is where they are. The perception of an ideological/civilizational struggle across the Global North has only grown, and history suggests it will keep growing and getting “hotter” over the coming decades.

Coke’s global exposure

Coca-Cola is most exposed to the threat of deglobalization and particularly a “hot” deglobalization.

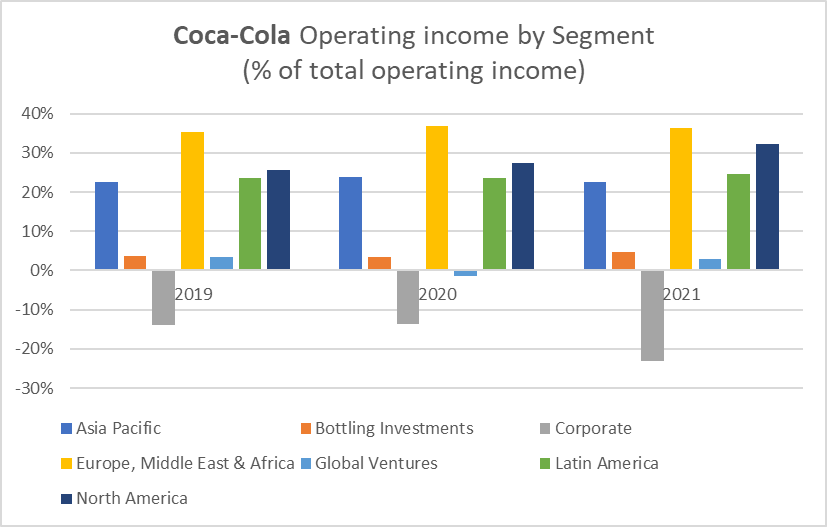

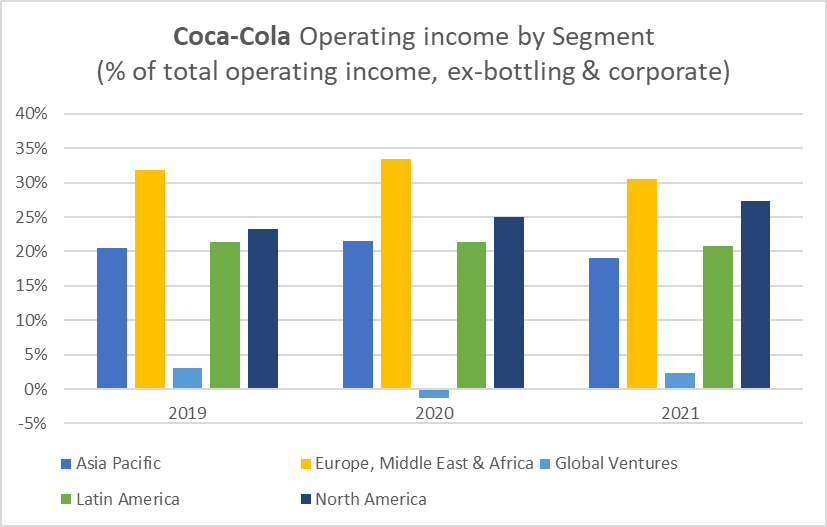

Chart B. Coke is globally diversified. (BusinessQuant.com)

On a regional basis, Coca-Cola’s profits are distributed quite evenly. In normal times, this might constitute a highly diversified regional portfolio with exposure to emerging market growth for one of the world’s most popular products.

Chart C. Less than 50% of Coke’s operating income comes from the Americas. (BusinessQuant.com)

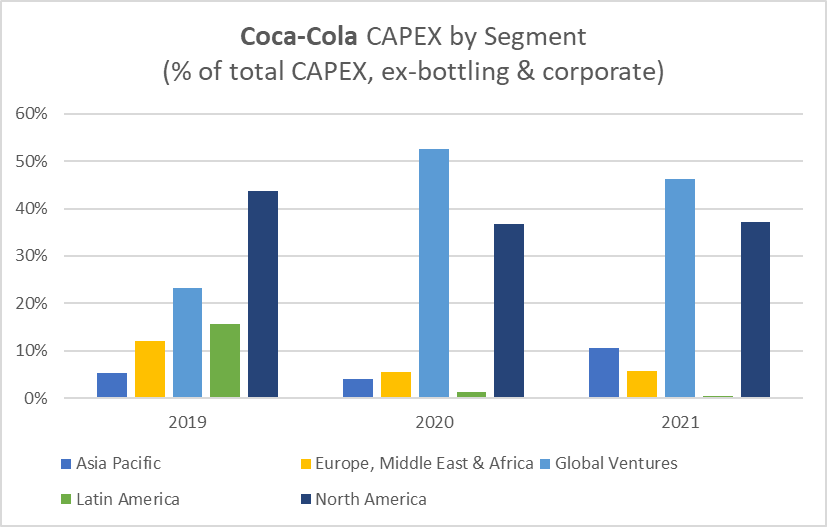

And, in that context, the relatively new Global Ventures segment (primarily composed of international, European-based coffee chain and juice acquisitions) might constitute a bold step forward in a promising new direction away from traditional sodas and towards more contemporary tastes. With the growing number of resources Coke is pouring into Global Ventures, as evidenced by its capex spending (and outside of the Americas generally, as well), it clearly thinks so.

Chart D. Coke is pouring resources into its Global Ventures division. (BusinessQuant.com)

Coca-Cola needs to maintain its European soda numbers but is largely banking on expanding its less traditional offerings outside of the Americas. Coffee chains, juices, and smoothies are likely to be directed towards middle class consumers, as well. Costa Coffee (the primary holding of Global Ventures) is, at least according to 2018 data, primarily centered in the UK and comes in a distant second in China.

Chart E. Coca-Cola’s Costa Coffee chain’s top 10 countries by location (2018). (Wikipedia/Business Insider)

Pepsi, on the other hand, is less geographically dispersed.

Pepsi’s global exposure

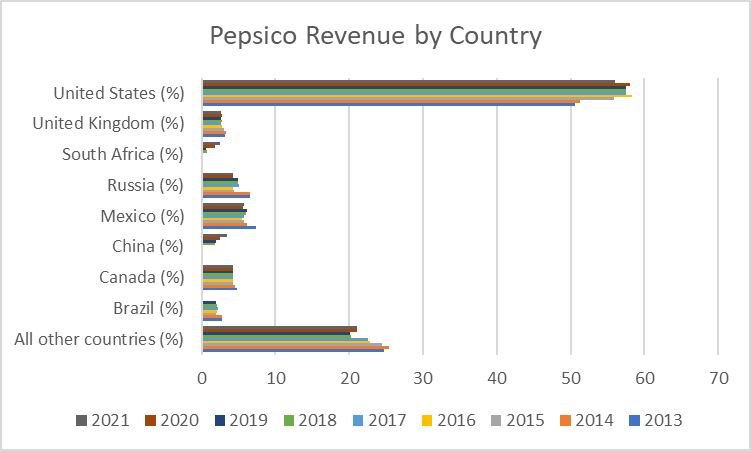

Chart F. Pepsi is more concentrated in the Americas, especially the US. (BusinessQuant.com)

Pepsi beverages have struggled to find a foothold outside of North America and Europe. Outside of those regions, PepsiCo relies on its snack and food products to drive revenue. Snack and food products (sold under the Frito-Lay and Quaker umbrellas) are also significantly more profitable.

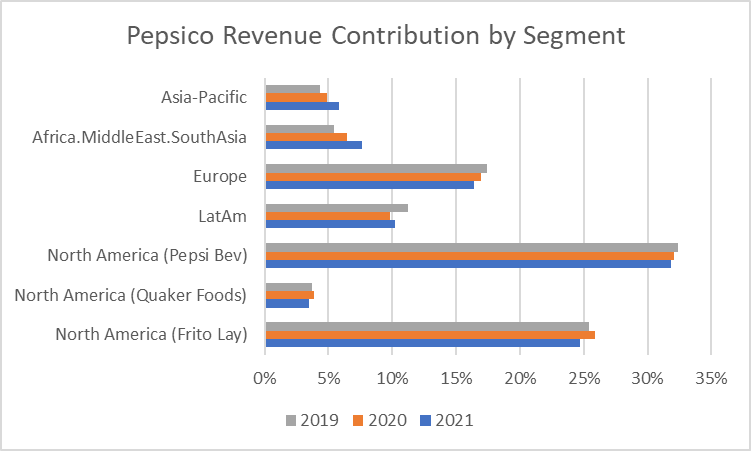

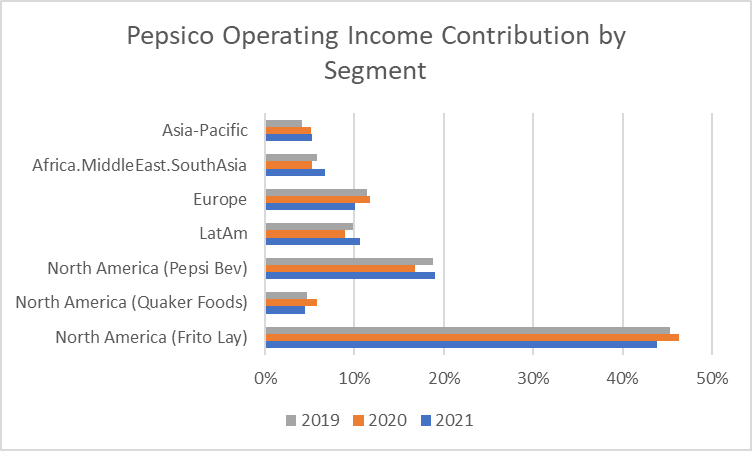

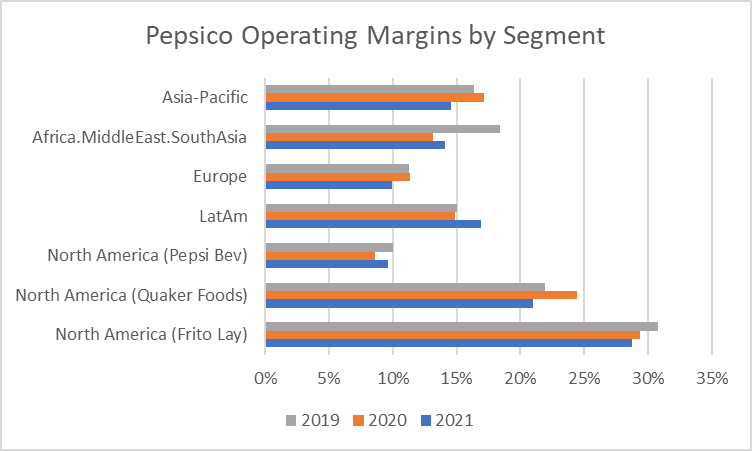

In the following charts, I have divided revenues, operating income, and operating margins by segment. Outside of the North American segments, food and beverage data is consolidated by region.

Chart G. PepsiCo revenue is much more heavily skewed to the Americas than are Coke’s. (PepsiCo’s 2021 10-K) Chart H. Nearly 80% of PepsiCo operating income comes from the Americas. (PepsiCo’s 2021 10-K)

Low margin segments tend to be more heavily tilted towards Pepsi beverages.

Chart I. Food- and snack-dominated segments tend to have higher operating margins. (PepsiCo’s 2021 10-K)

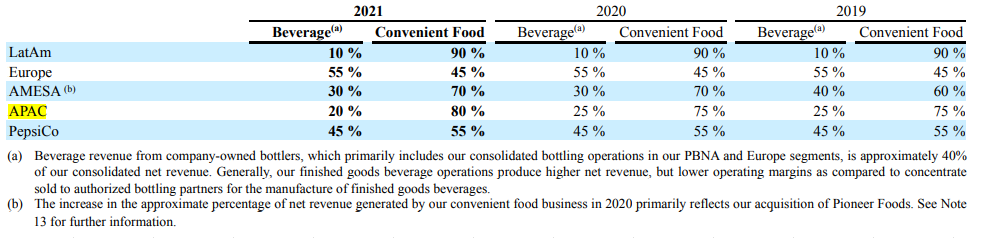

Asia-Pacific (APAC), highlighted below, has been pushing towards Latin American levels of food/beverage ratios, especially with the help of the 2020 acquisition of the Chinese brand Be & Cheery in a bid to become a leading snack maker there.

Chart J. Wealthier regions more likely to prefer PepsiCo beverages to snacks, but Asia-Pacific may be countering that trend. (PepsiCo’s 2021 10-K)

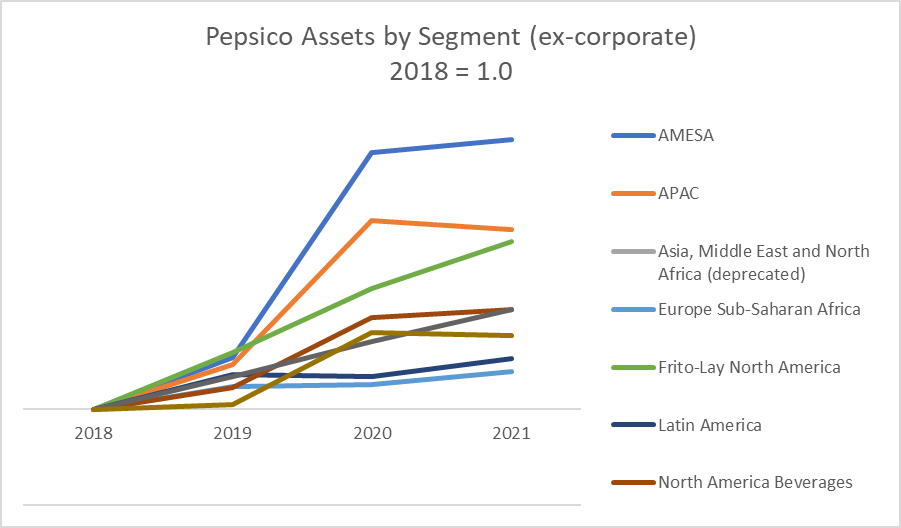

Just as Coca-Cola added a Global Ventures segment to its corporate structure, PepsiCo reorganized its structure to put greater emphasis on the Asia-Pacific, which had once been lumped into the now defunct AMENA (Asia, Middle East, North Africa) segment, which effectively became AMESA (Africa, Middle East, South Asia). And, the relative expansion of PepsiCo assets by segment (below) seems to suggest that they are pressing forward in and around the Indo-Pacific regions and primarily in snack categories.

Chart K. PepsiCo is expanding around Indo-Pacific. (BusinessQuant.com)

This makes perfect sense in a world where rising consumption of high-margin products in the Eastern Hemisphere can be expected. But, PEP’s price suggests an underappreciation by the markets of the risk that these expectations will not be met.

Nevertheless, there appears to be less exposure deglobalization and geopolitical conflict to Pepsi’s current portfolio than to Coke’s. Keurig Dr Pepper appears to be even less threatened by such risks, but it has risks of its own stemming from its greater reliance on selling a consumer durable product in its Keurig coffee makers.

KDP’s global exposure

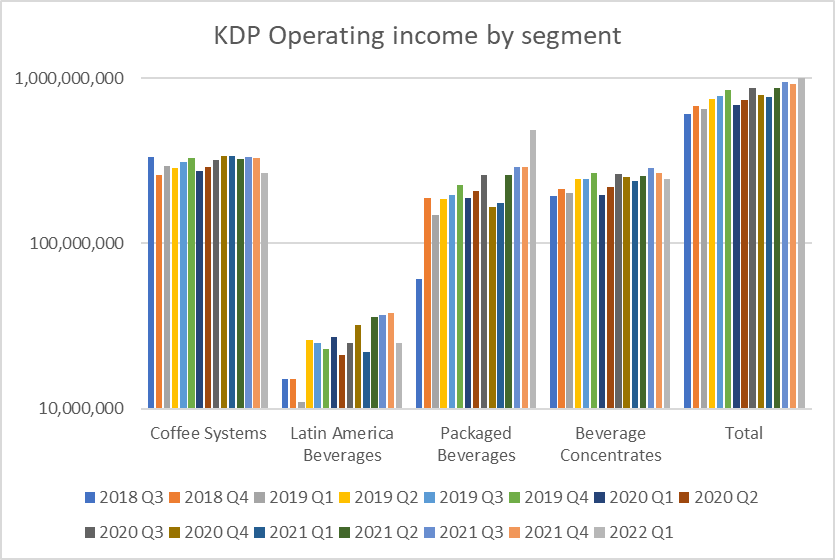

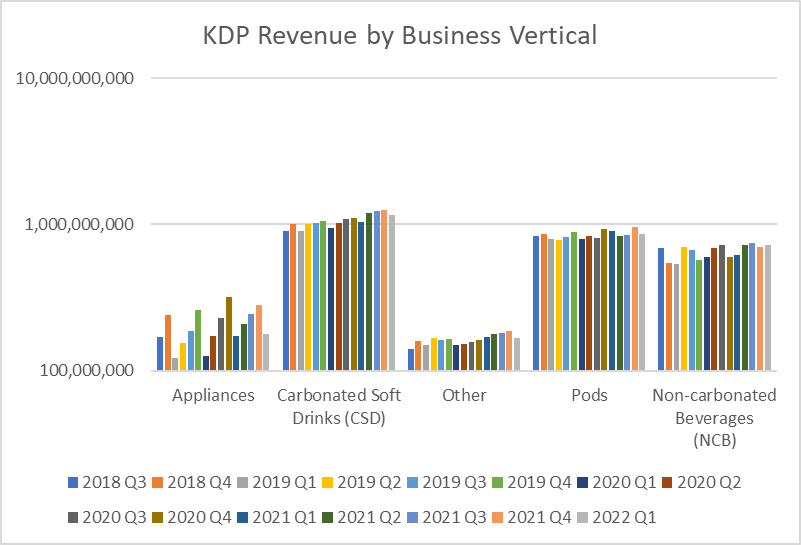

A near rock-steady 88-89% of KDP’s revenues come from domestic markets, according to Business Quant. Operating income is generally evenly divided across Coffee Systems (which includes both sales of the Keurig machines and their pods), Packaged Beverages, and Beverage Concentrates, although Packaged Beverages appear to have slowly gained share up until the first quarter of this year when the numbers leaped, especially at the expense of Coffee Systems (at least partly due to supply chain issues involving K-pods).

Chart L. Keurig Dr Pepper’s revenues come entirely from Americas. (BusinessQuant.com)

Revenues have been somewhat flatter across the board, although here again there is a slight uptick primarily in carbonated soft drinks.

Chart M. Revenue has been typically been stable across products, apart from coffee machine seasonality. (BusinessQuant.com)

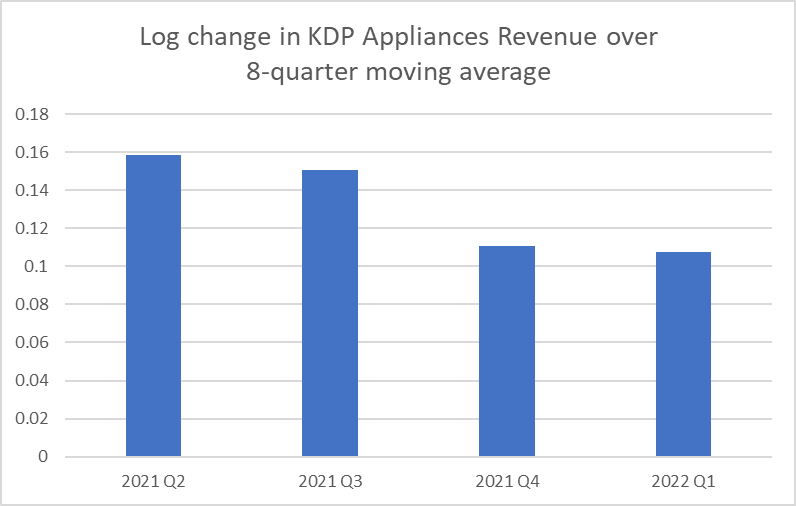

And deceleration in Appliances. Without longer-term data, it is hard to be sure, but it appears that growth is either in secular decline and/or that, even when adjusted for seasonality, it is cyclically sensitive. If it is the latter, which seems likely, then a steep cyclical decline could do long-lasting damage to KDP’s numbers, especially as this would likely feed into pod sales over time.

Chart N. KDP coffee machine revenues have been decelerating over the last year. (BusinessQuant.com)

In short, KDP’s New World-oriented business likely shields it from the most severe impacts of deglobalization, but its dependence on the durable goods end of its business makes it less well positioned as a defensive staple. That is both a concern over the course of a downcycle and a secular bear market, if for no other reason because secular bear markets have historically been composed of at least two cyclical bear markets (for our purposes here, recessions).

In terms of deglobalization, KDP appears to be the best positioned of the three and Coca-Cola the worst. Despite some of the weaknesses of KDP’s reliance on durable goods sales and Coca-Cola’s perennial brand power, I believe that deglobalization will prove the weightier factor. PepsiCo lands in the middle.

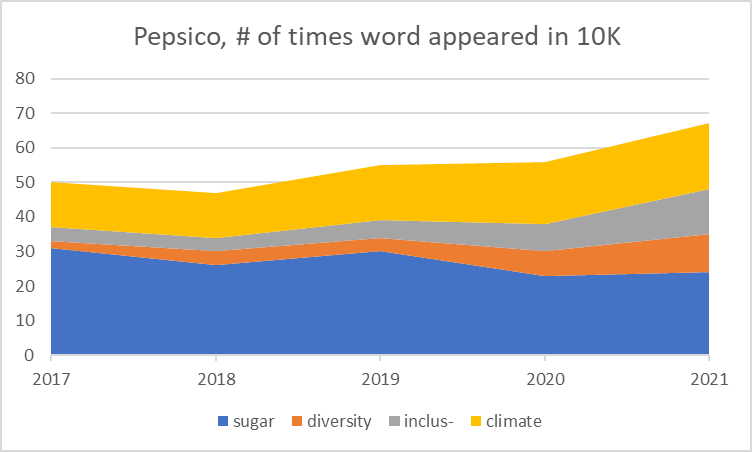

Domestic pressures

In North America, there has been growing social pressure to behave responsibly on a number of fronts, most famously on ESG metrics, although some of these have come under increasingly heavy criticism in some notable quarters. In any case, things have come a long way since Coke blew off the 1980 Olympics boycott. Of the three, Pepsi often seems to be the most vocal in its support of accepting the burden of social responsibilities and, according to its website, was recently ranked first among food, beverage, and tobacco companies. And, it includes sugar under its ESG umbrella.

The company says on its website:

We have set a goal to achieve 100 Calories or fewer from added sugars per 12 fluid ounce serving in at least 67% of our beverage portfolio by sales volume by 2025. Our goal is designed to shift a significant portion of our beverage portfolio towards lower added sugars levels that will help consumers to follow dietary recommendations. We are doing this by expanding our portfolio of zero- and lower-sugar beverages across the world.

I struggle with opaque sentences sometimes, so I am not exactly sure what the key metric is in that first sentence, but it sounds good. According to a report in Reuters last year, Silviu Popovici, PepsiCo Europe CEO, said that one-third of the company’s beverages sold in Europe were already entirely “sugar-free”.

Chart O. References to politically-tinged values have risen as references to sugar have fallen. (PepsiCo 2017-2021 10-Ks)

At the end of the day, however, all three of these companies are dependent, if to varying degrees, on selling sugar water, and Americans are becoming increasingly conscious of the dangers of sugar consumption. Earlier this year, Kris Sollid of the International Food Information Council (IFIC) said that 72% of American consumers claim they are reducing or avoiding sugar, “and the main way they are doing that is drinking more water versus caloric beverages”, as reported on Food Beverage News. In a recent IFIC survey, “45% of respondents rated eating less sugar as their top goal in 2022, topping weight loss and improved diet healthfulness”.

Mr. Sollid noted that consumers tend to look at “total sugars” rather than “added sugars” as the top item in the carbohydrate section of food labels, with total carbohydrates second and added sugars third, followed by dietary fiber and sugar alcohol. On the entire label, consumers look at calories, total sugars, sodium, total carbohydrates, protein and added sugars, in that order, with the latter two tied for fifth.

In the somewhat contorted quote from the PepsiCo website above, emphasis appears to be on calories and added sugars. The IFIC survey suggests that focusing on calories is a good strategy for soda companies but that sugars and carbohydrates are increasingly foremost in consumers’ minds. But, it is not yet clear to what degree these sentiments will translate into action.

The consumer is as the consumer does

According to the CDC, “obesity worsens outcomes from Covid-19”, probably the one thing nearly everyone can agree on when it comes to Covid and its repercussions. The good news for soda companies is that Covid-19 appears to have boosted “sugar-sweetened beverage” consumption among certain demographics, namely those who experienced “new financial hardships” during the pandemic. Children, too, may have increased soda consumption during the pandemic.

Whatever consumers may think about sugary drinks, they keep buying them, and when times get hard and finances tight, these drinks (and, in PepsiCo’s case, snacks) provide cheap, pleasurable calories. In the event of a downturn, the traditional sodas are likely to continue to prove among the most resilient consumer purchases.

Over the very long term, however it seems unlikely that either health authorities or individual consumers are going to unlearn what they have discovered about the considerable dangers posed by these drinks. As the state is increasingly forced to take financial responsibility for the health of its citizens, it is likely to tax and regulate sugary drinks and salted, oily carbohydrates to help pay for it. But one way or another, it seems increasingly unlikely that Americans will be consuming as much sugary drinks in 10 and 20 years as they are today.

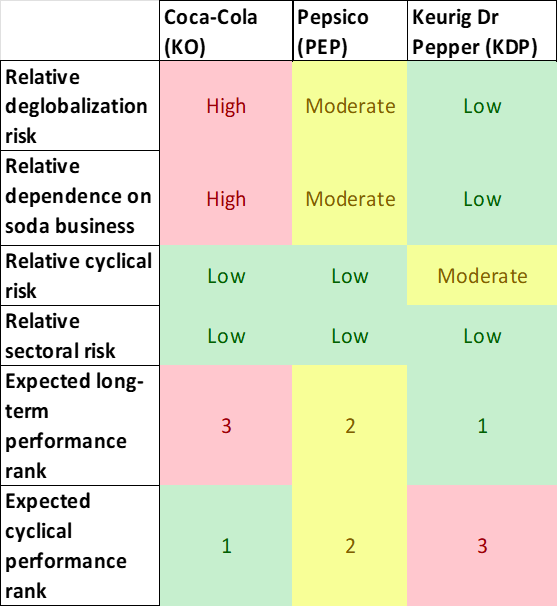

KO vs. PEP vs. KDP

Ultimately, over the long-term, because of the weight I put on both deglobalization and changing preferences in the home market, I believe Coca-Cola is likely to be the relative loser among the three, less because of what it has done wrong than because of what it has done right in terms of expanding into overseas markets during a period of rising globalization. KDP, largely because of its domestic coffee focus, is best positioned among the three. Over the short term, however, KDP is likely to prove the weakest of the three, since consumers are less likely to be willing to buy coffee machines as the economy sours than they are willing to buy cheap snacks and drinks. I think PepsiCo comes out second over both the long- and short-term scenarios, since it sits between Coke and KDP in terms of global exposure and global brand power. What is more, it is also likely to come in second if I have misidentified the larger historical trends. Although I think Pepsi comes in second, it is perhaps the best in terms of all-terrain capabilities.

In the following table, I have attempted to make the relative risks and opportunities somewhat more explicit.

Chart P. Relative risks and outlooks for KO, PEP, and KDP. (Author)

As we saw above, Coca-Cola is far more dependent on its overseas businesses (from Europe to the Pacific) than is PepsiCo, and it is trying to diversify into relatively more premium products (most notably coffee chains) in those markets just as the world is transitioning into a period of deglobalization and low growth. I see little reason, therefore, to be optimistic about its Global Ventures efforts to grow their business. Moreover, the Ukraine war and the political and social expectation in the West to divest from Russia makes clear the dangers to their established business lines, particularly in China. The outbreak of war in Asia would depress business by itself, but there is also the danger that Coca-Cola would be forced to pull out of China altogether because of domestic considerations. Although the future can never be known, these risks are now apparent, but they do not appear to be reflected in Coca-Cola’s PE multiple. Insofar as high PEs can be seen as an expression of expectations of high or growing future profits, these expectations seem unsustainable in the current geopolitical environment.

PepsiCo has similar headwinds. It, too, is trying to expand in China through its snack food acquisitions there, and it has significant exposure to the global economy. But, it is less exposed than is Coca-Cola, and that exposure is more concentrated in Latin America. Like Coca-Cola, it also has to face the growing aversion to sugary drinks in North America. The long-term trajectory is likely to be towards reduced consumption and greater regulation. This downward trend may be slowed by periods of economic hardship, as studies cited earlier suggest occurred during the height of the Covid crisis. Such pauses in the structural decline of soda consumption certainly cannot justify the multiples assigned to these companies. PepsiCo is somewhat less exposed to a downturn in the soda business because of its considerable snack and food portfolio. Although salty snacks are also under pressure of health considerations, the research cited above suggest consumers are more worried about carbs than salt and more worried about sugar, specifically, than carbs. Because Coke and Pepsi are nearly synonymous with soda (in some parts of the US, “coke” means “soda”), this actually makes soda an easier target. “Snacks” are differentiated enough, I suspect, to avoid as concerted attack. (On the food side, McDonald’s (MCD) and other fast food giants are the soda equivalents).

Keurig Dr Pepper has virtually no exposure to overseas markets outside of the Americas. Moreover, its revenues are skewed more towards coffee than sugary drinks or snacks. If it has a relative weakness, it is probably in its dependence on being able to sell coffee machines during a recession, especially a sharp recession. Even if they are intended to be loss-leaders, they appear to be cyclical. Thus, as recession fears grow (as opposed to long-term concerns), we might see greater weakness in KDP’s performance over the short-term (one to two years) relative to Coca-Cola or PepsiCo.

Conclusion

But, I expect all three stocks will be dragged down by the current cyclical downturn, which is the first chapter of a broad, long-term market decline. The difficulty here is that long-term bear markets have always been marked by cyclical volatility and sectoral rotations at both cyclical and “secular” intervals. This is something I have discussed in greater detail in earlier articles on the various sectors. In “secular” bear markets, for example, cyclicals like basic materials, energy, and industrials tend to outperform, but because such a bear market is highly cyclical, there are periods during the downswings in which these same sectors experience disproportionate losses. During the cyclical rebounds (within a secular bear), however they surge much higher than the noncyclical sectors. This is, at least in part, why the energy sector ultimately outperformed tech during the Great Depression. This effect is magnified in small caps. In fact, most of the structural, historical outperformance of small caps can be linked to this cyclical/secular interaction during bear markets. And, this seems to have held true for small-cap staples. During the Depression, for example, small-cap nondurables (nondurables include food and beverage manufacturers), despite having severely underperformed large caps and bonds during the worst of the downturn in 1929-1932, had outperformed both relative to the 1929 peak by the mid-1930s. This is illustrated in the following chart.

Chart Q. Small-cap nondurable stocks outperformed both Treasuries and large caps in 1929-1936. (Fama-French; Robert Shiller; St Louis Fed (own calculations))

Once the current cyclical phase of what I believe is a long-term bear market exhausts itself, therefore, the best deals are likely to be found in small-cap beverage makers rather than any of these giants. Since these cyclical bear markets usually take one to two years to work themselves out, there is time to see how much the world and the market change along the way to try to sort out precisely which companies are best positioned for that new world.

In the meantime, all three of these stocks will see depressed returns over the decade, driven primarily by dynamics largely beyond the control of the soda giants which carried them aloft for decades. One of those dynamics has been a “secular” bull market in all equity classes. Market returns have been too high for too long on a historical basis. This has been connected to unusually low levels of violent political conflict (even taking into account wars in the 2000s) and the opening up of vast new markets and pools of labor (i.e., globalization). These processes have begun to unwind, however.

Politicians, social movements, and states are moving in the direction of confrontation with one another and it is increasingly clear that they are willing to disrupt absolute economic stability for a number of relative social and political goals. Historically, these processes do not seem to stop until largescale death and destruction are employed. Setting aside the prospect of a total victory by one side or the other, it is not hard to imagine what a peace deal in Ukraine might have looked like, although it will likely take considerably more pain in either Europe or Russia for that to happen. Chinese ambitions are a wholly different matter. China has simply never been in doubt about its desire to fully absorb its would-be Lebensraum to the west, Taiwan to the east, and everything up to the Nine-Dash Line to the south. If Russians were unsure about their own place in the world after 1990, the Chinese have not. It must dominate East and Southeast Asia at a minimum; regime legitimacy is closely tied to this expectation; and this will cause disruption on the continent for the foreseeable future. In a word, the world is becoming less and less hospitable to sugary American consumerism.

As bearish as I am on the market as a whole and, indeed, on these stocks, I think there is a role for two of them in certain portfolios, primarily those which are heavily biased against risk and are in need of an upside hedge (this varies from investor to investor). Coca-Cola’s PE ratio, its global exposure, and its concentration in sugary sodas, however, likely preclude this. KDP is best positioned to outperform in a deglobalized world and de-sugarized US, but because its coffee machine business exposes it to cyclical pressures, I think it also has more cyclical downside. PepsiCo may offer a middle-way between Coca-Cola’s long-term risks and KDP’s short-term risks as it is more diversified in its product portfolio and more concentrated in markets geographically and culturally close to the US (relative to Coca-Cola) and less prone to recessionary shocks than KDP.

Of the three, if I could only buy and hold one stock to the end of the decade, it would be Keurig Dr Pepper. If I could only buy and hold one for the next two years, it would probably be PepsiCo. If I had to short one to the end of the decade, it would probably be Coca-Cola. And, if I had to short one for the next two years, it would probably be Keurig Dr Pepper.

Be the first to comment