gguy44/iStock via Getty Images

These days we’re overflown with doom messages like those of Jamie Dimon, the economy is going to tank, stagflation is making a comeback. We do think a recession is likely, but it will be a garden variety one and is already priced into growth stocks. Here is our reasoning.

How Did We Get Here?

Well, times have been very turbulent with the pandemic and then supply chain problems, and it’s been an environment that has been particularly difficult to navigate for central bankers. A few stylized facts:

- Most rich countries embarked on QE-type policies for much of the 2010s, despite dire warnings this hasn’t caused a blip in inflation, simply because it didn’t lead to any sustained credit boom.

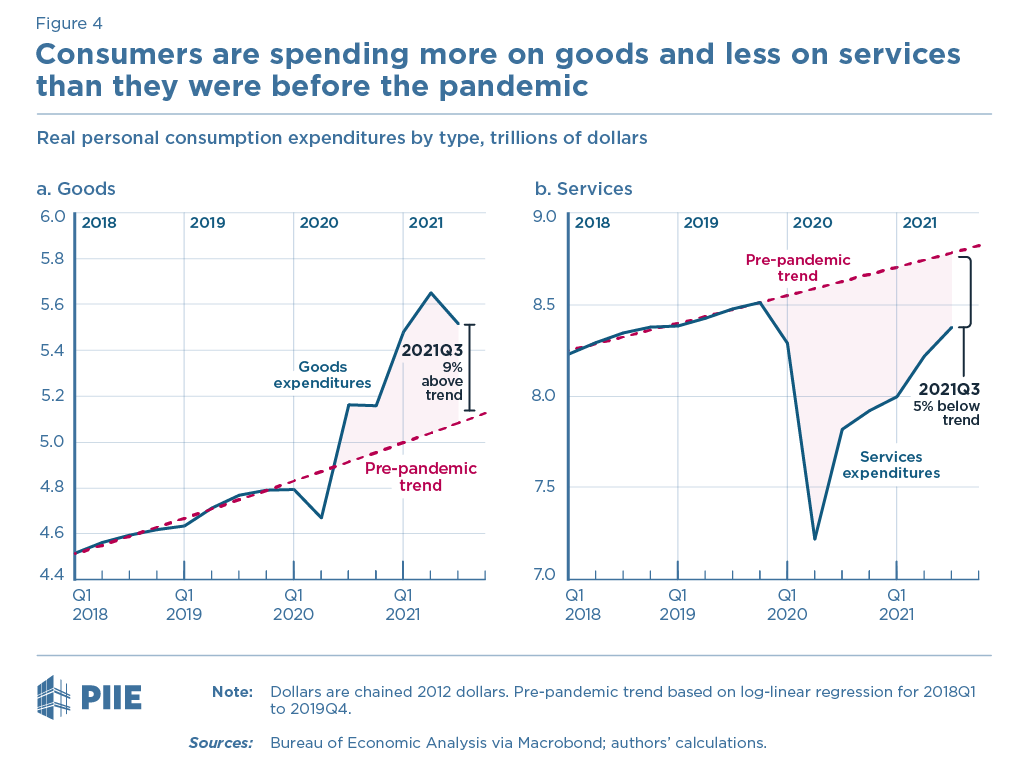

- The pandemic created all kinds of dislocations, shifts in demand, and supply bottlenecks. Most notably, it shifted demand away from services towards goods (think Peloton bikes, rather than the gym) and it produced a huge contraction in labor supply.

- The huge fiscal stimulus did what a decade of QE could not, directly bring money into people’s pockets and create a bit of a boom, but it was a one-off and Europe did much less of it and ended up with the same inflation nevertheless.

We give you some graphs to illustrate these points, first the huge pandemic-induced shift from services to goods:

PIIE

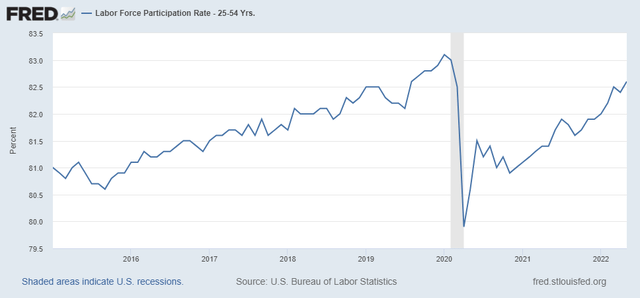

Second, the contraction in the labor supply, which hasn’t fully recovered:

There were good reasons to assume the inflationary surge would be temporary:

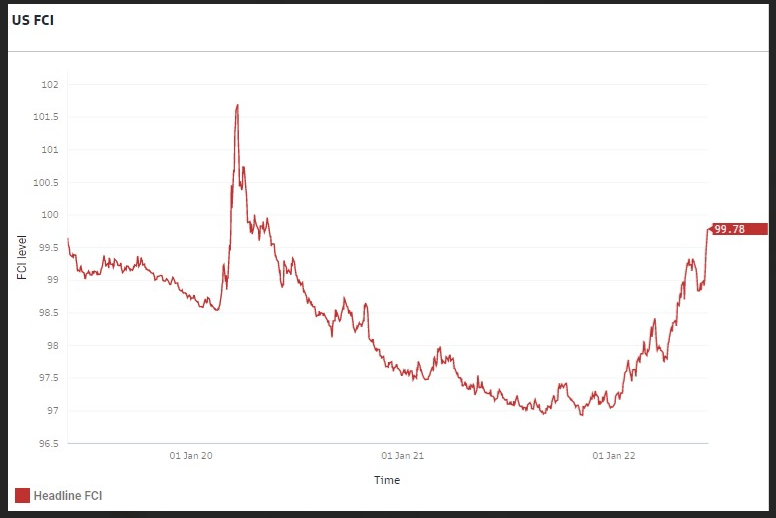

- Monetary conditions have already been going into reverse.

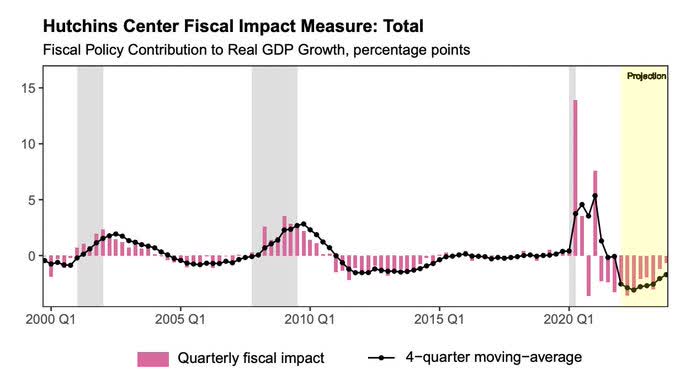

- The fiscal stimulus was a one-off and fiscal policy is already contractionary.

- The supply chain issues were mostly a result of the pandemic, expecting them to gradually be sorted out as vaccines became widely available wasn’t an unreasonable assumption.

Again, some data to illustrate, here the tightening of financial conditions was already well underway even before the Fed’s 0.75% hike this week:

Goldman Sachs

And here is how Goldman sees their own indicator (Reuters):

Goldman’s rule of thumb is that a persistent 100 bps FCI tightening slows GDP by about one percentage point after a year, in turn slowing inflation by roughly 0.1 percentage point.

There is some way to go as the effect on inflation is particularly small but the monetary contraction is so substantial that monetarists warning that it’s being overdone with steep rate hikes and quantitative tightening to the tune of $95B a month by September, from The Telegraph:

They fear that central banks will again ignore the signals and hit the brakes after a cyclical economic downturn is already underway. In short, the monetarists are today’s doves… Simon Ward from Janus Henderson says his key measure of the money supply — six-month real money (annualised) — is now sharply negative across the fourteen largest developed (G7) and emerging market (E7) economies.

Fiscal policy is also already contractionary:

Hutchins

From Hutchins:

Fiscal policy reduced U.S. GDP growth by 3.5 percentage points at an annual rate in the first quarter of 2022, the Hutchins Center Fiscal Impact Measure (FIM) shows. The FIM translates changes in taxes and spending at federal, state, and local levels into changes in aggregate demand, illustrating the effect of fiscal policy on real GDP growth. GDP fell at an annual rate of 1.5% in the first quarter, according to the government’s latest estimate.

With both fiscal and monetary policy already sharply in reverse, we nevertheless experienced a continued surge in inflation as a result of worsening supply chain problems, which were given a new impetus by the Chinese lockdowns and the Russian invasion of Ukraine and subsequent sanctions.

Why No 1970s Style Stagflation?

We might very well get a recession on the back of a sharp reversal in both fiscal and monetary policy, as well as a steep fall in the stock market and consumer sentiment.

It turns out sentiment is actually a pretty reliable indicator pointing to a coming recession, from Prospect:

We examined data on consumer expectations from both the Conference Board, an international research organisation, and the University of Michigan, and found that this data predicts every one of the last six US recessions called by the NBER several months before they happened. Our data also does not falsely predict recessions that didn’t occur. This data is now in recession territory in 2022, suggestive of an imminent US downturn… Over the last year, consumer expectations in the US fell by more than they did in 2007. We also have Conference Board data on the eight biggest US states, including California, Florida and Texas—and just as occurred in 2007, consumer expectations have collapsed and are predictive of recession in each state.

And, of course, we have the likes of Larry Summers who argues that with inflation at 8%+ and unemployment well below 4%, from Fortune:

If you look at history, there has never been a moment when inflation was above 4% and unemployment was below 5% when we did not have a recession within the next two years.

Also, purchasing power is under strain as wage growth can’t keep up with rising prices, especially and this will create problems especially at the bottom of the wage building where the propensity to spend is highest.

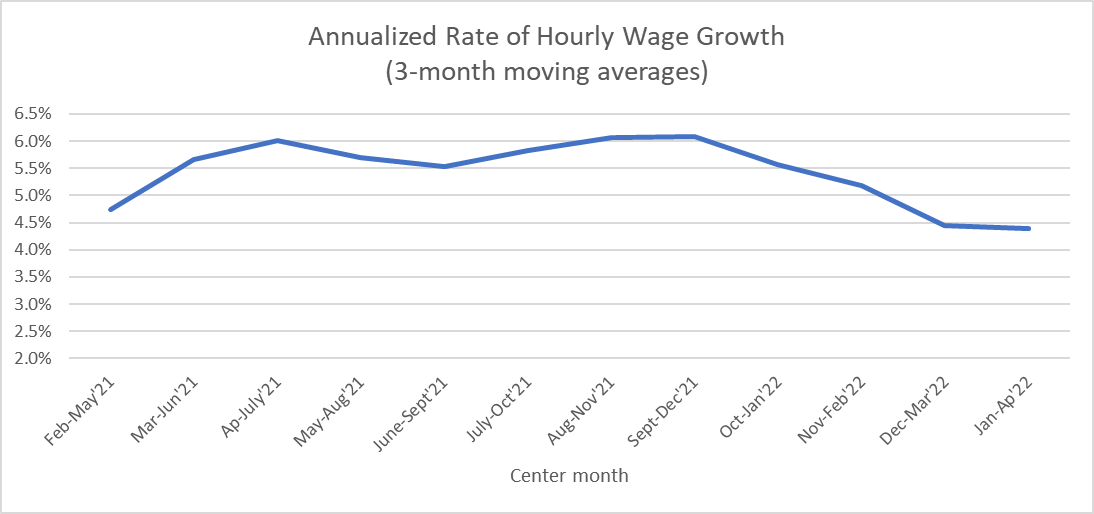

But there is the catch. For stagflation to become embedded a wage-price spiral is needed to form and this is simply not happening. In fact, despite a super-tight labor market, wage growth has actually moderated considerably of late:

Counterpunch

And with the fiscal and monetary contraction in place, we’ll see a considerable deceleration of economic growth and job creation, which is likely to further moderate wage growth.

Lower economic growth will also moderate demand and prices for commodities, but the joker in the pack is what will happen to supply chains. Many have underestimated these, and this is likely to be a long slug. A nice segment by segment overview is provided by Morningstar:

Field points to a few bright spots. Labor availability has improved in key areas, such as ports, to help move goods across the world. Companies have been signing long-term contracts with shippers to secure transportation, which was normally a buy-it-as-you-need-it market prior to the pandemic, Field says. Some of the industries most significantly hit by global supply chain shortages include semiconductors, automobiles, industrials, retail, and restaurants. Below, we’ll highlight how issues have progressed for each of those industries.

The used vehicle price index has been coming down as well. None of these are close to being resolved, but there is at least a modicum of progress in certain fields.

One could even argue that the steep rate hikes create a bit of a headwind, as these could lower the required investments to alleviate supply chain problems.

Investor Takeaways

Given the amount of demand destruction (contractionary fiscal and monetary policy, falling stock market, rising mortgage rates, falling real wages, slumping consumer sentiment etc.) we think a recession is very likely.

What is not likely is inflation to become entrenched, as a necessary ingredient, wage growth is already moderating and is likely to moderate further in the face of sharply lower growth and soon rising unemployment.

Give this backdrop, inflation is liable to moderate considerably with the caveat that we expect a slow but positive grind in alleviating supply chain problems, but this remains a difficult area to make predictions because of a lack of historical precedent.

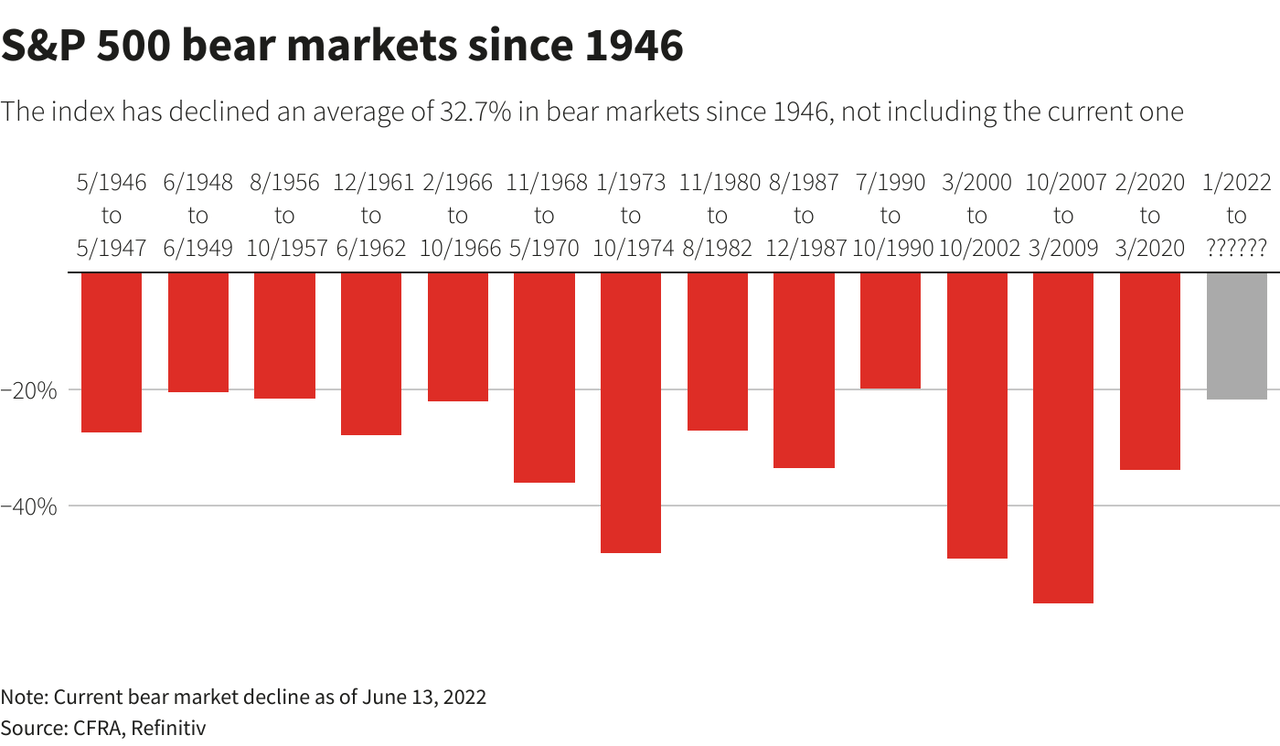

How deep can stocks fall? Here is some comparison from previous bear markets:

Reuters

We think a recession is likely but will be mild, and we don’t see much reason to fear any systemic risk like in 2008 (although we keep a wary eye on Italian-German bond spreads), nor do we think shares were as overvalued as during the dot.com bubble.

The most likely scenario is a garden variety recession, but with the added downside from a steep bond market selloff. We think most growth stocks have already priced in this scenario, but asset prices are liable to undershoot as well as overshoot, so the selling might not be done yet.

But valuations are certainly becoming attractive here.

Be the first to comment