peterschreiber.media/iStock via Getty Images

Introduction

We wanted to write this article to give you our view of what we think is quality when it comes to investing and why it’s almost always systemically undervalued. There’s a cliche that many investors know and it comes down to

In the market, you have to pay up for quality.

If it means that you have to pay a higher multiple for a quality company, then we absolutely agree. However, if it means that you have to pay an expensive price and sacrifice future returns to own quality, then we don’t agree at all with it. This might sound confusing, but hopefully, you’ll understand what we mean by the end of this article.

First things first, let’s see what we mean by quality.

What is Quality?

Even though we don’t like to group businesses according to their characteristics, we will separate them into value, growth, and quality in this article.

We understand as value those companies that are optically cheap when an investor looks at their relative multiples. This cheap valuation might come from the underlying business suffering a tough period. Value investors will research the company. If they see that the tough period is temporary and deem that the company is undervalued with respect to its intrinsic value, they’ll invest in it. The objective of value investors is to make most of their return through multiple expansion once the market realizes what the company is really worth.

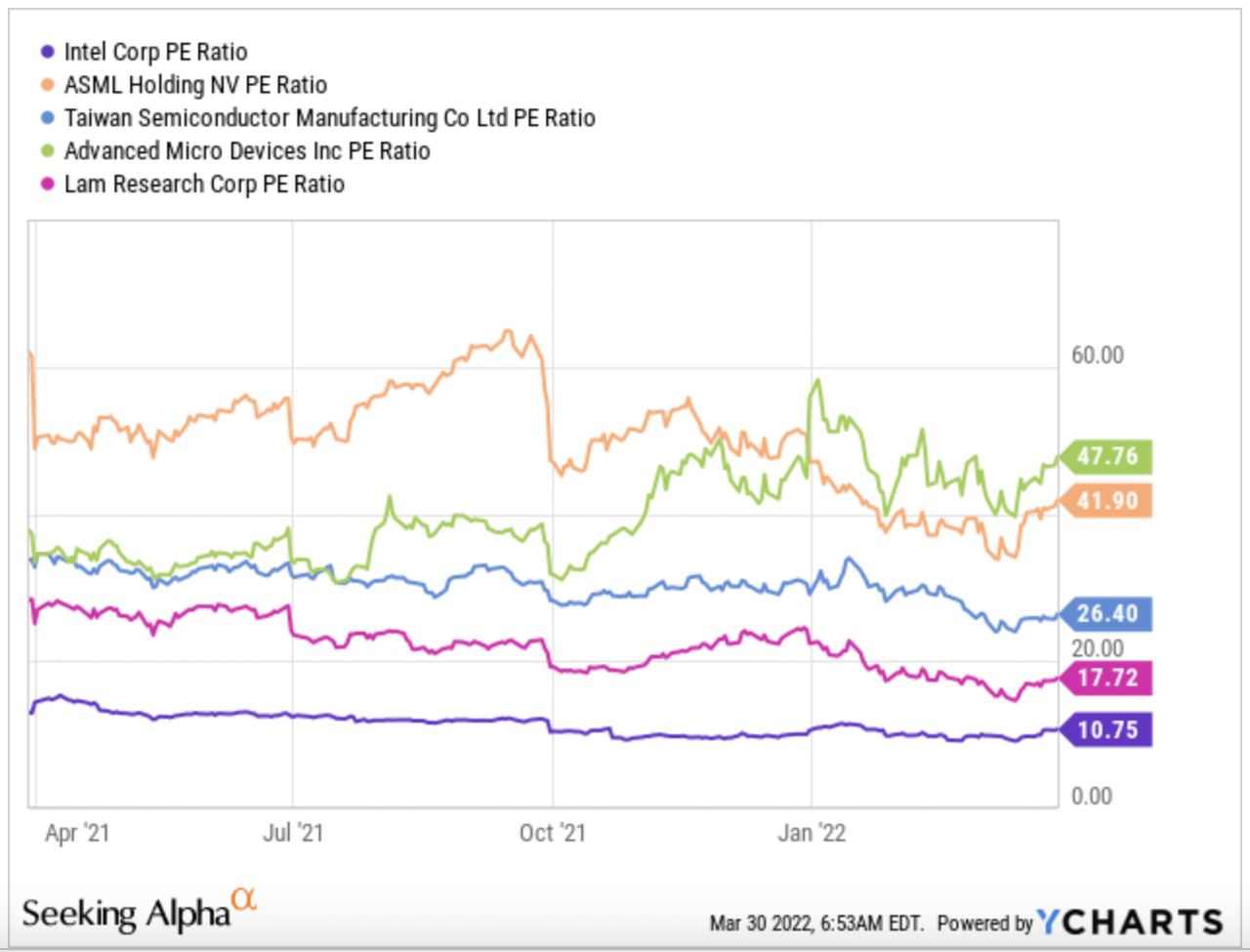

As an example of value, we understand a company such as Intel (INTC) right now, where the multiple is extremely low compared to the rest of the semiconductor companies, and investors are hoping for a “turnaround,” so to say:

YCharts

The market has clearly lost its faith in Intel, but if management manages to turn sentiment around, Intel investors might make an excellent return just through multiple expansion. Multiple re-rates that follow sentiment changes typically occur fast, so value investors don’t typically need to hold a company for too long to realize their return.

The father of value investing, Benjamin Graham, prescribed taking an aim, for example, 50% or 100% higher, and a maximum holding period to get to that aim, and that should be no more than 3 years. As a sidenote, it’s ironic that his best investment, which made him successful and rich, Geico, was an investment that didn’t follow these rules.

Of course, this analysis is extremely simplified as some of the companies included in the graph are not remotely comparable. Still, it was just an example to explain what we meant.

In growth, we include fast-growing companies that enjoy long runways ahead. Investors will buy these companies at rather expensive multiples hoping that they can sustain this growth for long enough to generate decent returns, even accounting for a multiple compression when the business slows down (they always do).

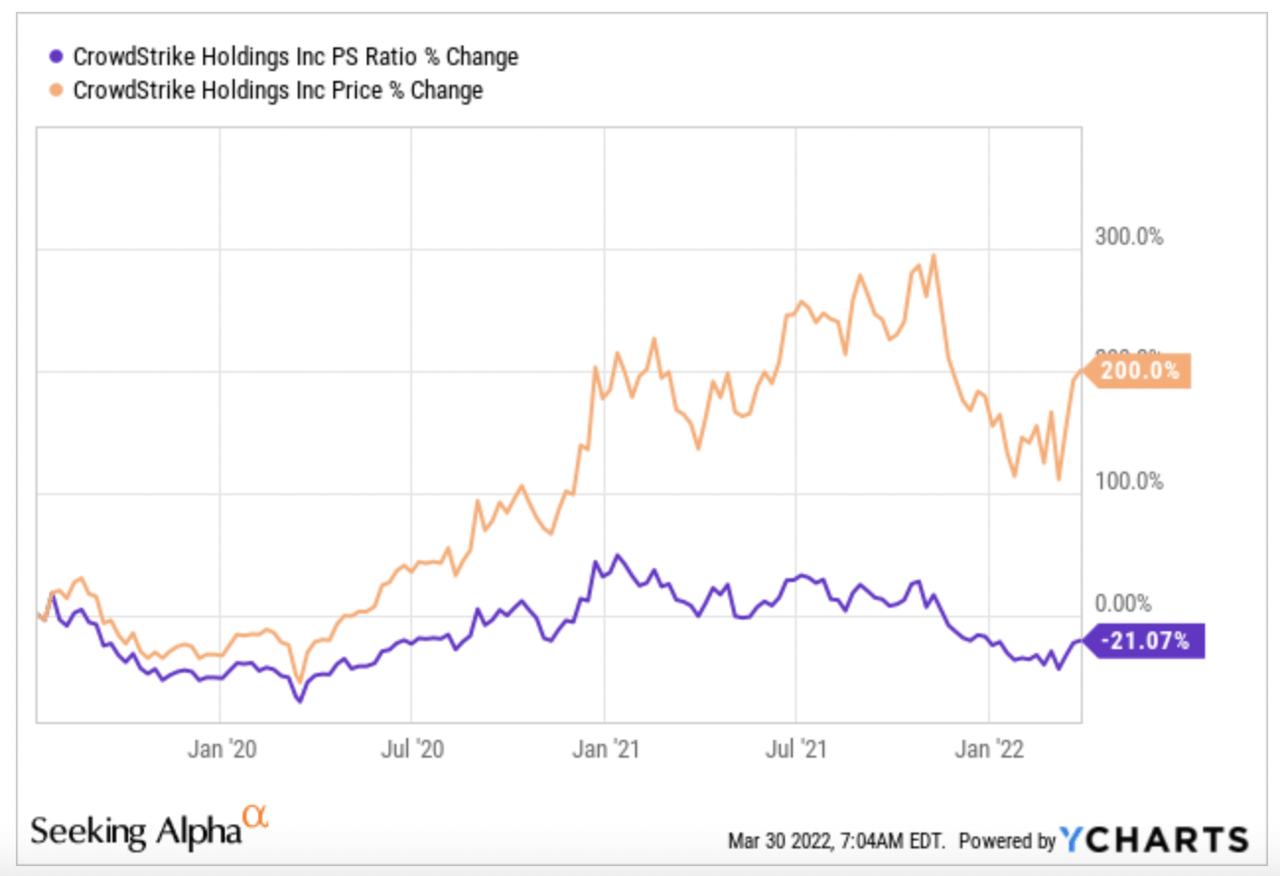

A good example of a growth company is CrowdStrike (CRWD). In the summer of 2019, many investors could not understand that someone would like to buy the company at more than 45x sales. However, those investors who did are sitting on 200% gains despite a 20% multiple compression:

YCharts

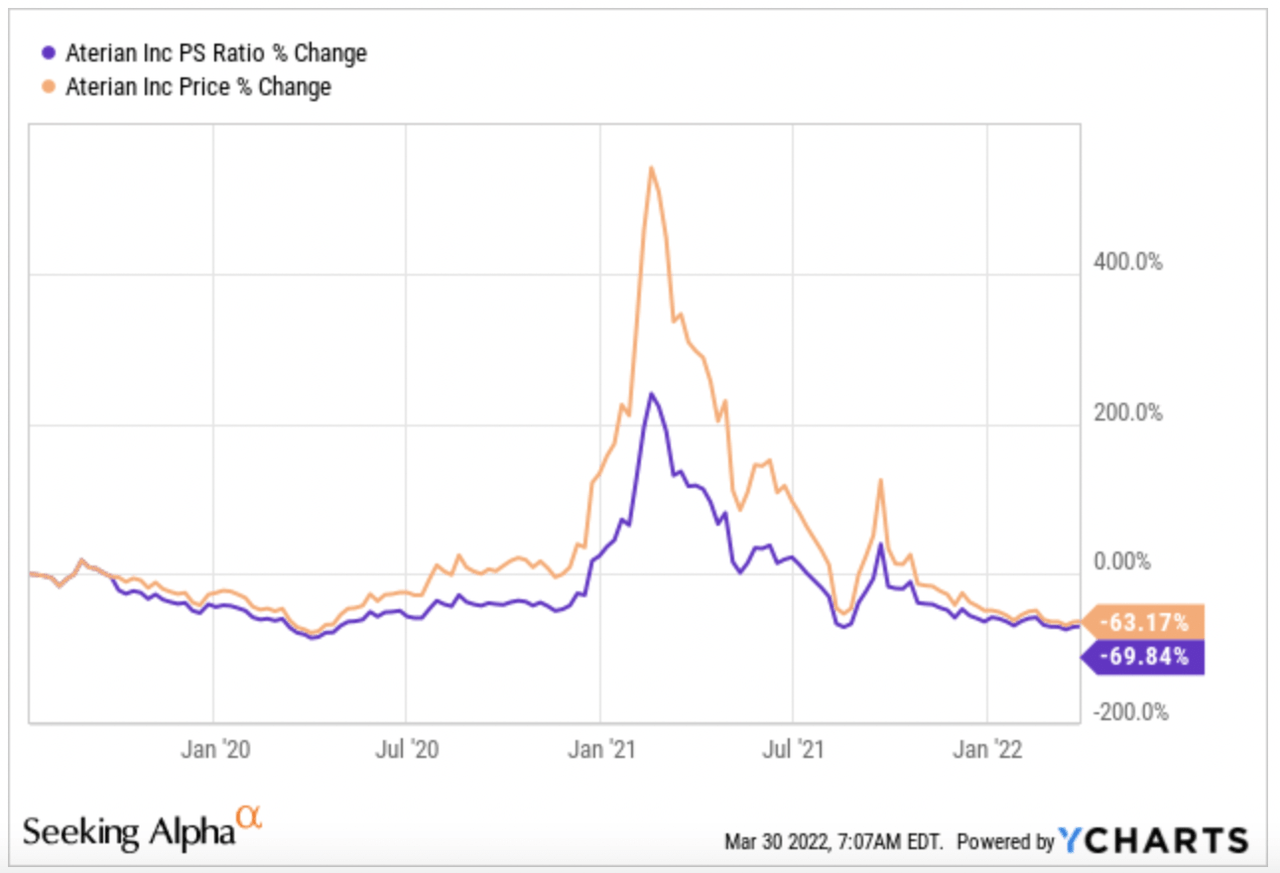

Often, the potential returns in growth companies are larger than in value companies, although the downside risk is also higher. If a richly-valued growth company goes out of favor, multiple compression can be very violent. You just have to look at Aterian (ATER) over the same period as CrowdStrike:

YCharts

High-quality and high-growth can be found in the same company. However, in this article, we would like to explain high quality in the context of established companies with strong moats. Growth companies are typically building out their moat, so they are somewhat riskier. So, what is quality in this context?

Quality is much more subjective than the previous two groups, as companies are seen very differently through different eyes. For example, we might argue that Constellation Software is a high-quality company, while someone might take the opposite side. We personally categorize a company as high-quality if it can score great numbers in the following categories: well-financed, resilient, and a compounding machine.

Made by Best Anchor Stocks

The order matters here as we ordered them according to how much investor judgment these characteristics require. The one to the left requires little investor judgment, while the one on the right requires substantial investor judgment. This order is non-coincidentally the same as the order of importance (nobody said investing was easy!). So, the one on the right is the most important, and the one on the left is the least important, albeit all are important.

Well-financed is pretty straightforward. You’ll be able to understand if the company is financed adequately by answering the following questions:

-

Does the company have low debt?

-

Does it have plenty of cash to weather difficult times?

-

Is the EBIT/Interest expense ratio above 3x?

-

Is the company cash flow generative?

-

Is stock dilution adequate?

There are more things to look at, but if the answer to all of these questions is “Yes, ” you have most likely found a well-financed company. Holding a well-financed company is not only crucial for the survival of the company, but it’s also important because it gives the company more optionality. If all of the company’s cash is tied to paying debt, then it leaves little room for management to reinvest that money into the business.

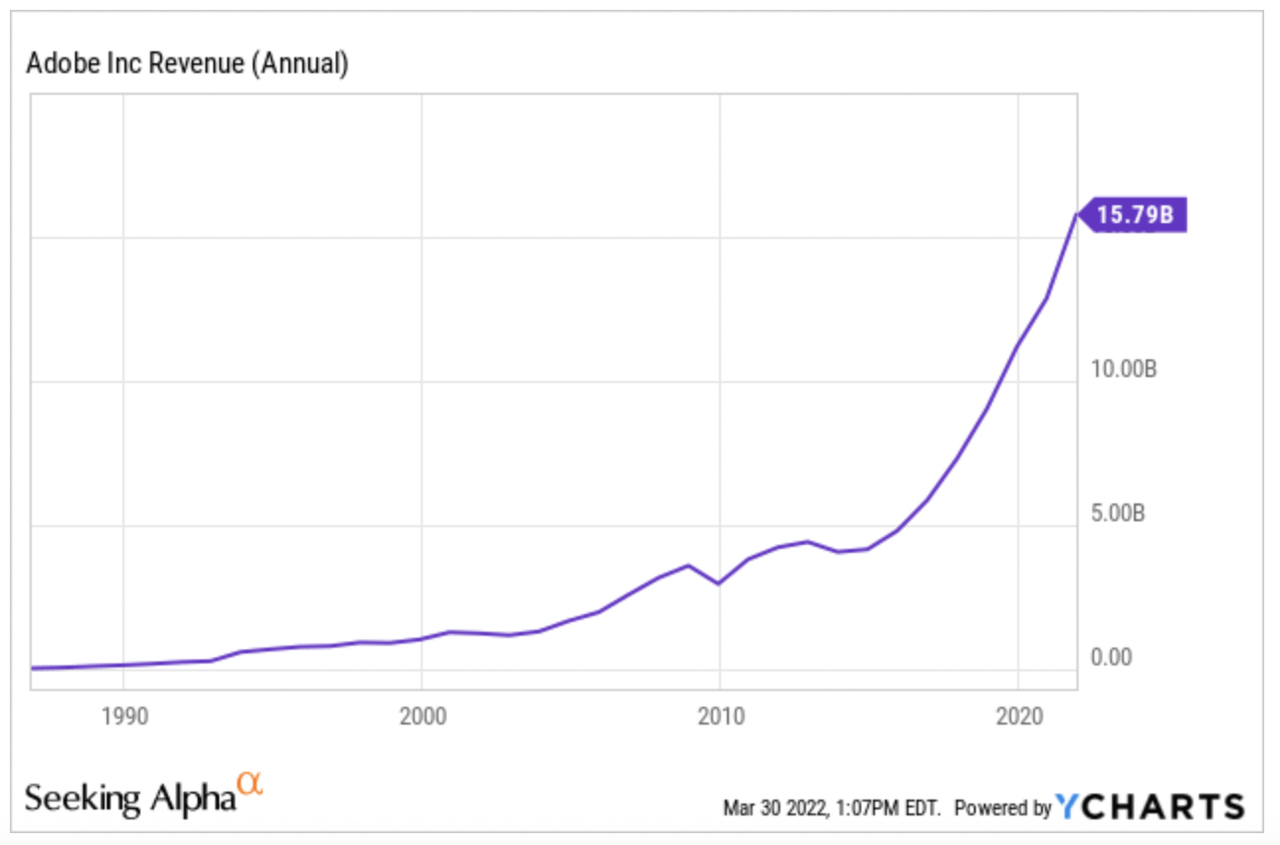

Seeing if the company is resilient is already a bit more complicated. You have two methods two analyze this. First, you can go to the most recent economic crisis and see how the company fared. However, this might be challenging as the last significant crisis was in 2008, a period when some companies were not even publicly traded yet. On top of this, companies might have changed quite a bit since 2008, so the comparison might not be the best. An excellent example of this last limitation is Adobe (ADBE). If we check how the company fared in 2008, revenue decreased quite a bit, so we might be inclined to think that it’s not a resilient business:

YCharts

However, during the decade that followed the crisis, management completely transformed the business from a product-based business to a subscription-based business, so it’s much more resilient now.

The other way to understand a company’s resiliency and probably the best is trying to understand what the company sells and how it would perform during a crisis. For example, if you buy a cyclical company like a bank, most likely, a crisis will bring some tough times for the business. Its financial position will deteriorate quickly, and if the recession is long-lasting, it might even end up in bankruptcy if it’s not well-financed.

These two first characteristics of quality companies (well-financed and resilient) are oriented towards the company’s survival under any scenario. If we want to hold a company for the long term, we need it to be able to survive during tough periods. It’s pretty delusional to hold a company for 5+ years, expecting the whole path to be smooth.

Once we have closely analyzed that our company can survive a very tough period, we can turn to the other characteristic of quality companies: being a compounding machine. Now, what do we mean by this?

A company generates value for shareholders if it can reinvest cash back into the business at higher rates than its cost of capital. Saying it differently, if ROIC (Return on Invested Capital) > WACC (Weighted Average Cost of Capital), then the business is generating value. If we inverse the relationship, the company is destroying value. To be characterized as a compounding machine, a company must be able to deliver a higher ROIC than its cost of capital (and here comes the important part) during a long period.

This is easier said than done because two forces will naturally try to make ROIC mean revert until it’s equal to the cost of capital. One is competition, and the other one is diminishing marginal returns.

-

Competition: if there’s a high return on capital in any industry, this will lure in competition, and in the absence of significant competitive advantages, these news companies will eat the company’s lunch and lower its ROIC.

-

Diminishing marginal returns: as a company finds itself with a larger capital base to deploy back into the business, it will have to distribute it over more ventures, some of which will not be profitable and will lower its overall return. In these cases, returning this capital to shareholders is preferred rather than burning the cash in the business. However, many management teams keep investing more cash despite the burn because if you deploy a small capital base, you don’t move the needle.

With high-growth stocks, you often have to judge on the potential for high ROIC, as they typically are investing heavily into conquering market share to later have that pricing power that is necessary for great ROIC. As most industries show that a few winners take a huge part of that business, it’s necessary to give up ROIC initially to make sure you are one of the few companies that lead the industry. Once you are there, then you can start focusing on ROIC.

Analyzing if a company has the potential to be a compounding machine is not easy at all. It requires a deep understanding of the competitive environment and the company-specific and industry-wide growth opportunities. The important thing is to focus on the future to understand for how long ROIC will be higher than the cost of capital. A high current ROIC is mostly irrelevant if it mean-reverts fast due to competitive pressures or due to management burning cash in the business. Compounding machines have three things in common: a moat, optionality, and a secular tailwind. Without these three, it’s impossible to enjoy a sustained period of compounding at high rates of returns.

Of course, no company can be well-financed, resilient, and a compounding machine without a high-quality management team. If you plan to hold for more than 5 years, we would recommend starting your research with management. If management doesn’t give you a good feel or you don’t think that you will be able to trust them, it’s better to not invest or even sell if you have already invested. It’s simply not worth it, no matter how strong the business currently is. A business might have some inertia and can continue executing for some years, but if the market doesn’t like the new management team, it will punish the company through often extreme multiple compression, and investors will be left holding a loss.

Made by Best Anchor Stocks

These four aspects of a business should help you understand whether it’s a high-quality business. Maybe analyzing if the company is a compounding machine is the trickiest part, but one would assume that many people are capable of getting to the same conclusion. So, why doesn’t everyone hold these companies? The answer is in the price and the assumptions used to derive their intrinsic value.

Why quality companies always appear overvalued but are systemically undervalued

The valuation of public equities is a somewhat controversial topic, and all the controversy comes from the fact that it’s completely subjective. We liked this quote by Warren Buffett in his most recent annual shareholder letter:

Please note particularly that we own stocks based upon our expectations about their long-term business performance.

Investors should hold what they think is cheap based on their own expectations, not what is cheap based on the market’s expectations. So, for example, if you believe that a company can sustain a 15% growth for the next 5-10 years, but the market thinks that this growth is sustainable only during the next 3 years, then the stock will probably appear much cheaper for you than to the market. Plain and simple. And here is precisely where our edge as long-term investors lies: duration.

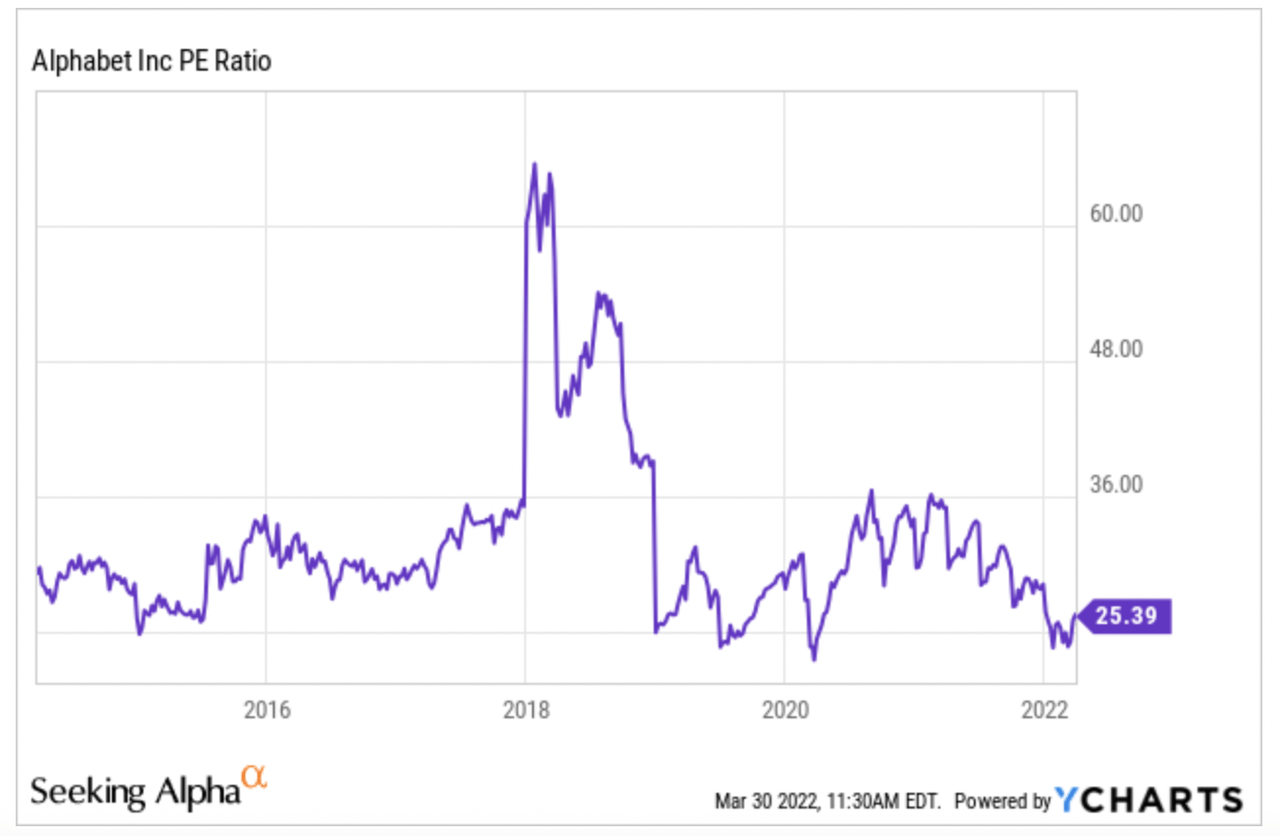

High-quality companies enjoy acceptable and durable growth, but the market always thinks that these companies are trading at a premium. Let’s go to the typical examples. If we look at Alphabet (GOOG) (GOOGL), according to many, it was expensive back in 2016, trading almost at 36x earnings:

YCharts

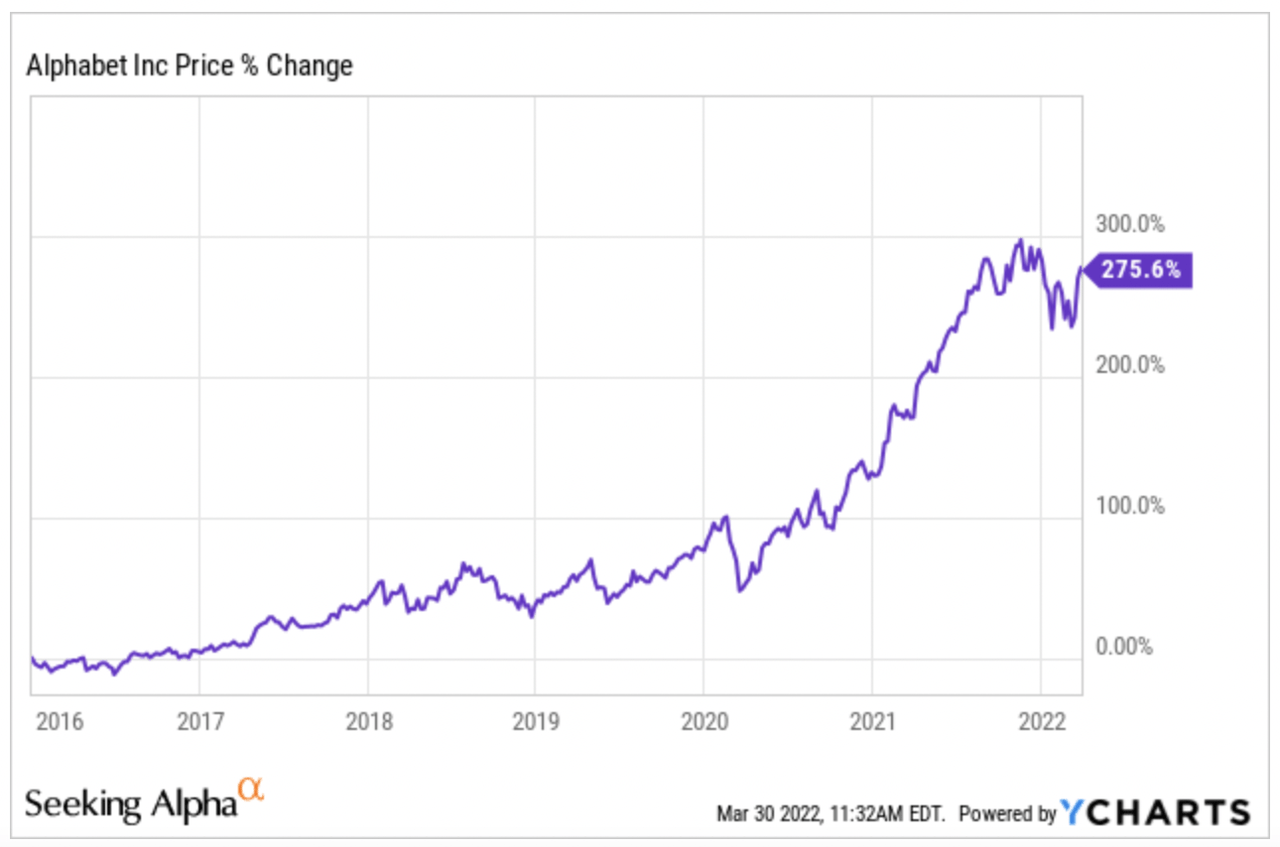

Those investors that passed on the company because they overlooked the durability of the company’s growth missed a return of 275%:

YCharts

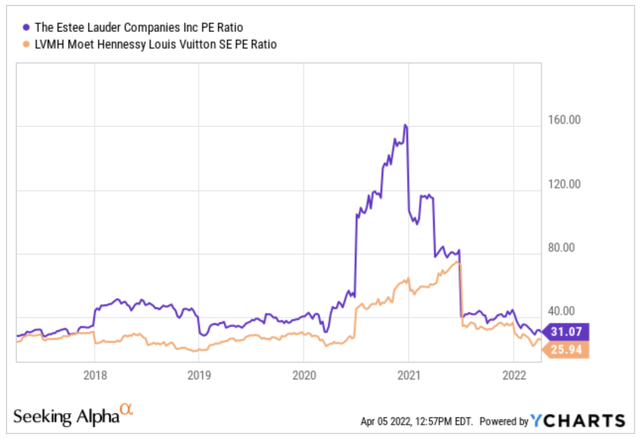

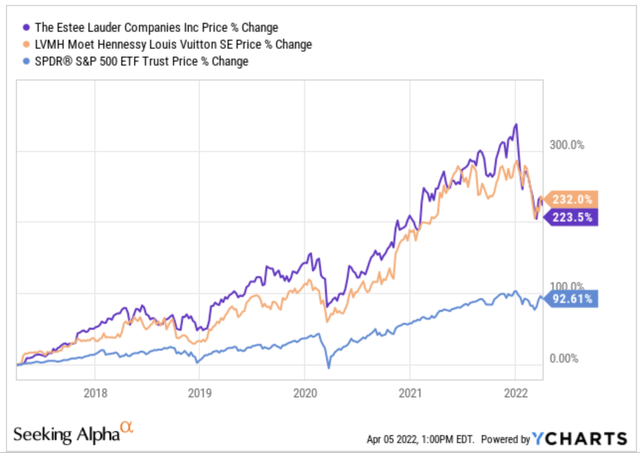

The company comfortably beat both indexes, so clearly, there was some sort of mispricing, right? It was optically expensive but ended up being realistically cheap. This has happened to many quality companies, such as Estee Lauder (EL) and LVMH (OTCPK:LVMHF). These companies looked very expensive (above 20 P/E for non-tech companies) 5 years ago:

However, they have delivered market-beating returns that were not dependent on multiple expansion:

You could say that this is hindsight bias and we would agree to a certain extent, but the market has demonstrated time after time that it’s not good at pricing durable growth stories. Why? We think that it’s related to the tool that most people use.

Many investors love DCF models (discounted cash flow). Many investors try to justify valuations with DCFs, and many will never buy a stock if the intrinsic value is not above what the company is trading at. You could argue that it’s a way to protect your downside and increase your margin of safety, but it’s also a great way to miss some of the best investments you could have ever made.

The DCF model is limited in that it typically only incorporates a maximum of 5 years and then drops the growth rate to what is called a terminal rate. With this terminal rate, you would then calculate the terminal value for the fifth year onwards.

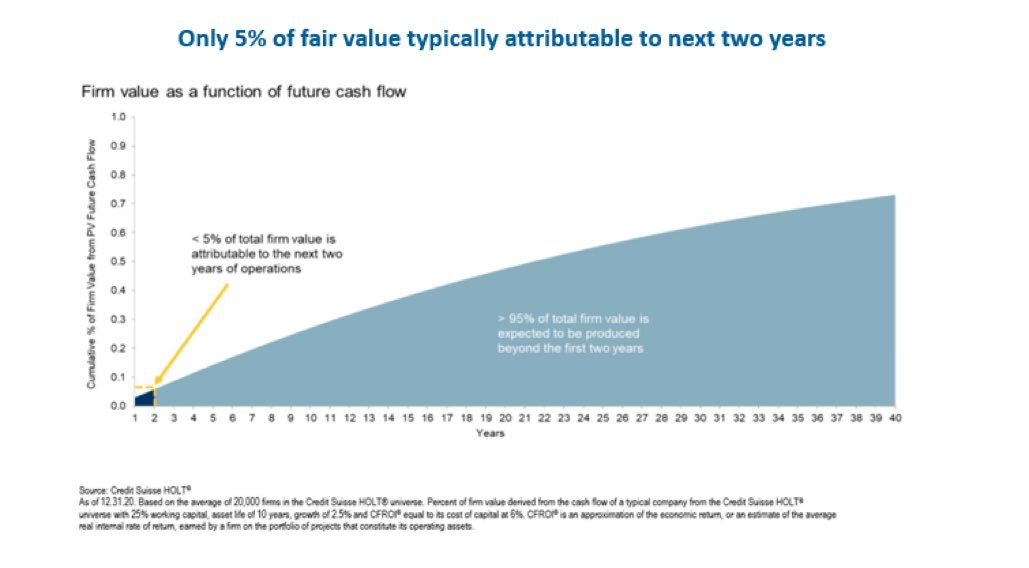

Terminal rates illustrate what you think the company will be able to achieve in the very distant future. Terminal rates are typically low, a bit higher than the expected GDP growth rate. The problem is that many use the terminal rate in the fifth year, but high-quality companies generate most of their value after the fifth year, as they can keep growing at a higher pace for a long time, and this is when compounding really does its job. This graph shows what we mean.

Credit Suisse

Most of the intrinsic value for a company lies in the distant future, but investors focus on the next 2-5 years. With this view, they are missing plenty of intrinsic value in their calculation which is why under a DCF model, high-quality will almost always appear overvalued. If a high-quality company appears reasonably valued or even overvalued (to a certain extent) using a 5-year conservative DCF, then it’s most likely grossly undervalued.

For long-term investors, this mismatch between the DCF model and the actual intrinsic value of a high-quality company is where the opportunity lies. The market will always overweight current growth and will consistently underweight duration, but the reality is that the latter is the most crucial. High-quality companies are more durable than 5 years, so take advantage of it.

Conclusion

We hope this article helped you see why looking for high-quality companies is so important and why the market systematically undervalues them if you look at the long term. Winning against the market over the short term is often a difficult task, but the way the market works gives long-term investors an edge. We know what side we want to be on.

In the meantime, keep growing!

Be the first to comment