jetcityimage/iStock via Getty Images

Vroom, Inc. (NASDAQ:NASDAQ:VRM) was a COVID pandemic darling, as its innovative business model was in the right place at the right time. While Vroom’s current low stock price may appear to be a steal, there is still no evidence Vroom has a path to profitability. There are structural reasons why Vroom’s business model has inherently lower gross profits than conventional dealers. Vroom is also spending far too much on compensation on a per-unit basis. Until the situation changes, I don’t see any reason why investors should get involved with Vroom.

Brief Company Overview

Vroom, Inc. is an ecommerce platform for selling used vehicles. Rather than traditional used vehicle platforms such as autotrader that simply connect buyers and sellers, Vroom is an end-to-end platform that handles the entire transaction with no-haggle pricing and contact-free at-home pick-up and delivery.

Hugely Successful IPO

Although Vroom was started in 2013, it really came to the public’s attention during the early days of the COVID pandemic, when social distancing measures kept consumers at home. Vroom’s innovative at-home pick-up and delivery model was just what consumers needed.

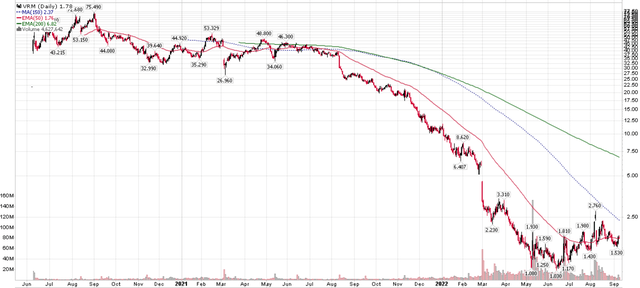

Based on a 160% YoY gain in Q1/2020 revenues and early investments by Cascade Ventures (Bill Gates’ family office), Vroom launched an initial public offering of shares in June 2020. Ultimately, Vroom was able to raise over $460 million in a hugely successful IPO, with shares opening at $35 / share versus the IPO price of $22. VRM shares traded as high as $47.50 on day one, and reached a peak of $75 in September 2020 (Figure 1).

Figure 1 – Vroom stock price (stockcharts.com)

Unfortunately, guidance was soon cut, and a large equity issuance signaled the peak in the stock price. Vroom’s stock lingered for many months in the $30 to $50 range, before it started to plunge precipitously in mid-2021, to a low of $1.03 in June 2022. Since the bottom in June, shares have since recovered somewhat to $1.70, but it is still down 92% from the IPO price and 98% from the peak.

Vroom’s Financial Model Was Flawed From The Get-Go

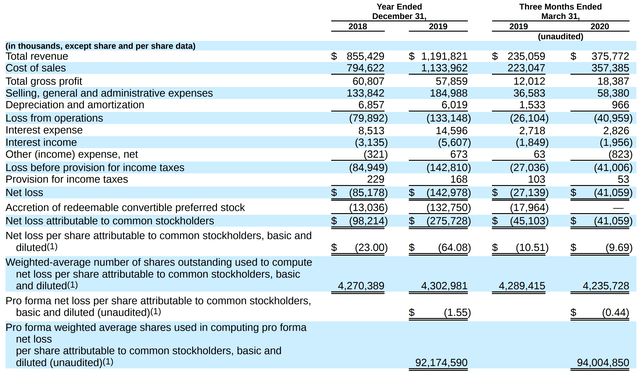

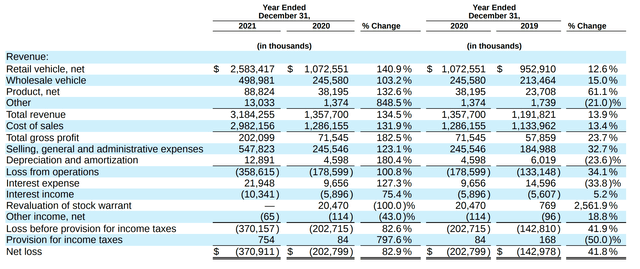

Figure 2 shows Vroom’s condensed financials from the prospectus. Notice that despite recording $1.2 billion in revenues in 2019, Vroom only generated gross profits of $58 million, or 4.8%. Gross margin and gross profit both declined in 2019, even though Vroom sold 89% more cars.

Supporting this skinny gross margin, Vroom had rapidly expanding SG&A expenses, as it was a “tech” company. In 2018, Vroom spent 2.2x its gross profits in SG&A, and in 2019, that figure rose to 3.2x.

Figure 2 – Vroom IPO financials (Vroom S-1 Prospectus)

Simply put, the more cars Vroom sold, the more money it lost!

Investors Should Have Realized Something Was Amiss

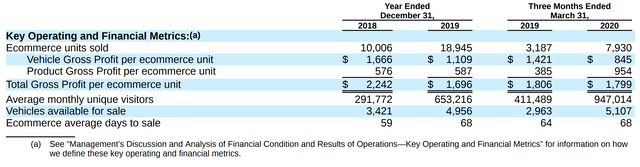

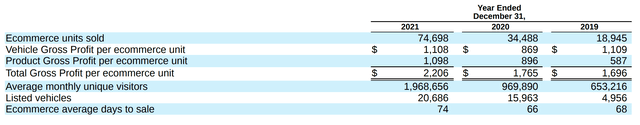

Looking at per vehicle figures, investors should have realized something was amiss. In 2018, Vroom generated $2,242 per vehicle in ecommerce gross profits (Figure 3).

Figure 3 – Vroom gross profit per vehicle (Vroom S-1 Prospectus)

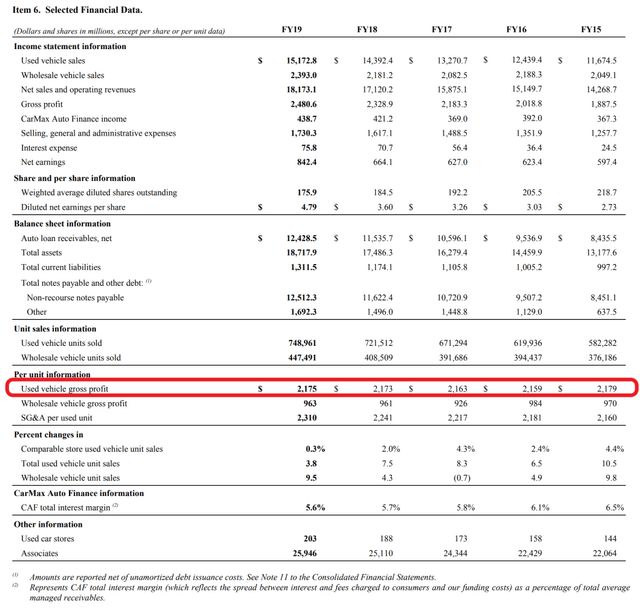

This figure was broadly similar to CarMax’s (KMX) per vehicle gross profits, from years 2015 to 2019 (Figure 4).

Figure 4 – KMX condensed financials (KMX 2019 10K)

However, we see that in 2019, Vroom’s per vehicle gross profit was only $1,696. It appears Vroom was accepting a lower gross margin to drive growth, in preparation for an IPO.

Vroom’s low margins persisted in the first few quarters post-IPO, as its investors were paying up for growth (Figure 5). However, e-commerce margins did rebound in 2021 to ~$2,200 per vehicle, as Vroom benefited from the massive used vehicle shortage of 2021.

Figure 5 – Vroom 2021 Ecommerce gross profits (Vroom 2021 10K)

Overall, financial results continued to underwhelm, as Vroom spent multiples of gross profit in SG&A, with SG&A being 3.4x 2020 gross profits, and 2.7x 2021’s gross profits (Figure 6).

Figure 6 – Vroom 2021 financials (Vroom 2021 10K)

I have made this comment many times in other articles, but the “build it and they will come” corporate strategy is not sustainable. A business simply can’t outspend its revenues and gross profits if it wants to be sustainable in the long-run.

Is It Time To Buy?

With the stock hitting rock bottom recently at $1.03, is now a good time to buy shares of Vroom?

A look at the latest quarterly financials suggest the answer is no.

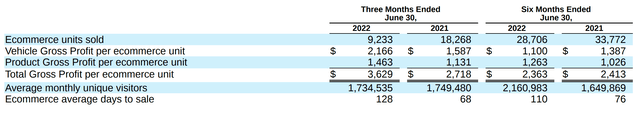

First, on the positive side, Vroom reported Q2/2022 e-commerce gross profits of $3,629 per vehicle, a big jump from $2,718 in Q2/2021. However, reading the quarterly report, it appears the gross profit jump YoY is a little misleading.

In February 2022, Vroom completed the acquisition of United Auto Credit Corporation (“UACC”) and began to report financing revenues (interest income and gains on sale of finance receivables) as part of its e-commerce business unit. The comparable period in 2021 did not have this finance revenue line item. Furthermore, when competitors like CarMax discuss gross profit per vehicle, that figure is simply sales price less acquisition cost.

Figure 7 – Vroom Q2/2022 Ecommerce gross profit per vehicle (Vroom Q2/2022 10Q)

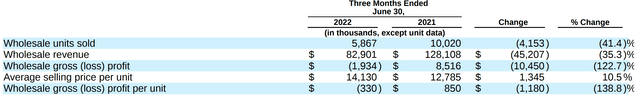

Also, we see that Vroom’s Wholesale business has fallen into a gross loss of $330 per vehicle (Figure 8). This could imply Vroom had mispriced trade-in values, or had held onto inventory for too long, as used car pricing softened in the quarter.

Figure 8 – Vroom Q2/2022 Wholesale gross profit (Vroom Q2/2022 10Q)

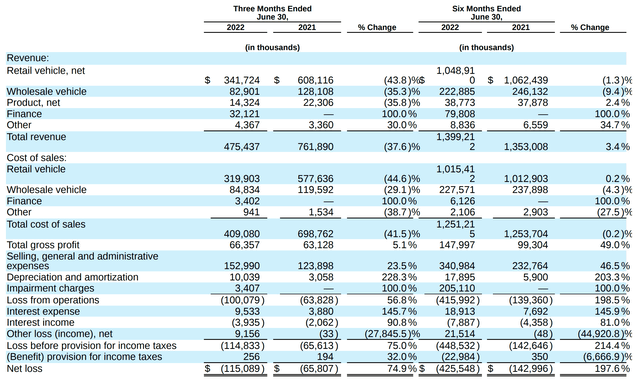

As discussed briefly above, gross margin can be used as a lever to control the pace of growth. For example, Vroom could increase unit volume growth by overpaying for purchases to secure vehicles or underpricing sales to get vehicles off the lot. In Q2/2022, it appears Vroom chose to raise gross margins and slowdown the pace of growth, as we saw a sharp slowdown in cars sold for Vroom (50% YoY decline), leading to overall revenues declining by 38% YoY (Figure 9).

Unfortunately, the slowdown in sales did not have too much of an impact of SG&A, as it still grew 24% YoY to $153 million, and it continued to represent ~2.3x of gross profits in H1/2022. Note for comparison’s sake, CarMax’s SG&A as a % of gross profit was only 75% in the latest quarter, which was actually much higher than in prior years. Historically, CarMax’s SG&A as a % of gross profit runs at ~70%.

Figure 9 – Vroom Q2/2022 financials (Vroom Q2/2022 10Q)

To me, it appears the economics of Vroom’s current business model just isn’t working. It is spending far too much on SG&A as a % of gross profits. This is an interesting result, because the whole premise of e-commerce is that businesses didn’t have to incur brick and mortar costs.

So, far from factual evidence of this premise, it appears the opposite is true, as CarMax, with 225 physical locations throughout the United States, is highly profitable (F2022 net income of $1.2 billion) based upon roughly similar gross profits per vehicle of ~$2,000 per vehicle.

Why Vroom’s Business Model May Be Structurally Challenged

To understand why Vroom’s business model may be structurally challenged, let’s first look at the company’s definition of cost of retail sales and SG&A (the relevant sentences have been highlighted by the author):

Retail cost of sales primarily includes the costs to acquire vehicles, inbound transportation costs and direct and indirect reconditioning costs associated with preparing vehicles for sale. Costs to acquire vehicles are primarily driven by the inventory source, vehicle mix and general supply and demand conditions of the used vehicle market. Inbound transportation costs include costs to transport the vehicle to our VRCs. Reconditioning costs include parts, labor and third-party reconditioning costs directly attributable to the vehicle and allocated overhead costs. Cost of sales also includes any accounting adjustments to reflect vehicle inventory at the lower of cost or net realizable value.

Our selling, general, and administrative expenses, which we refer to as SG&A expenses, consist primarily of advertising and marketing expenses, outbound transportation costs, employee compensation, occupancy costs of our facilities, professional fees for accounting, auditing, tax, legal and consulting services and software and IT costs.

First, on the gross profit per vehicle, it is my understanding that when Vroom purchases a vehicle, the company ships the vehicle to a central reconditioning facility to be cleaned, checked, and detailed. The cost of this shipping is included in inbound transportation costs. On the other hand, brick and mortar dealers like CarMax or a local used car dealership do not have to incur said shipping costs, as a lot of the work is done in the dealership. Unless Vroom can convince consumers to sell their cars to Vroom at significantly less than intrinsic values (which is unlikely since consumers can easily get a competitive quote from their local used car dealership), Vroom should have lower gross profit per vehicle because of this transportation cost.

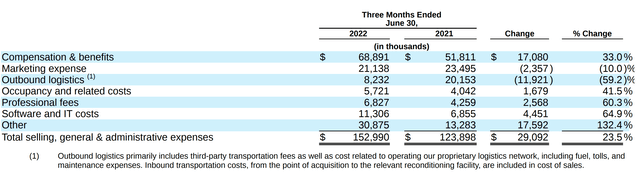

Next, let’s move on to SG&A. Once the cars are reconditioned and sold to consumers, they need to be shipped to the consumers’ location from Vroom’s central facilities. This is captured by outbound transportation costs. In Q2/2022, outbound transportation costs were $8.2 million, a decrease from $20.2 million in Q2/2021 (Figure 10). This result is likely explained by Vroom’s lower units shipped. On a per unit basis, outbound transportation costs were $888 in Q2/2022 vs. $1,106 in Q1/2022.

Figure 10 – Vroom Q2/2022 SG&A (Vroom Q2/2022 10Q report)

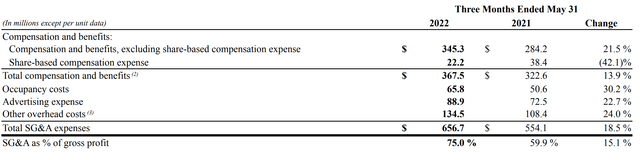

True, Vroom does incur significantly less occupancy costs than brick and mortar dealers, as it only had $5.7 million in occupancy costs in Q2/2022, or $617 per ecommerce unit sold in the quarter. However, we need to put this into context. For the latest quarter, CarMax sold 240,950 used vehicles and incurred $65.8 million in occupancy cost, or $273 / unit sold (Figure 11). So CarMax’s dealership network is more “productive” than Vroom’s central facilities.

Figure 11 – CarMax Q1/F23 SG&A (KMX Q1/F2023 10Q report)

Also, my sense is that Vroom views itself as a technology company selling cars, rather than a used car dealer that has an e-commerce presence. In the company’s own words:

Vroom, Inc., and its wholly owned subsidiaries (collectively, “the Company”) is an innovative, end-to-end ecommerce platform that is transforming the used vehicle industry by offering a better way to buy and a better way to sell used vehicles.

What this means is that the company may be spending a lot of SG&A on computer programmers to develop the e-commerce platform, so while it saves on “used car salesperson” costs, it may spend even more on web development and pricing algorithms. For Vroom, it takes $7,460 in compensation & benefits to sell 1 vehicle in Q2/2022. For CarMax, it only costs $1,525 in compensation & benefits to sell 1 vehicle in the latest quarter (comparing VRM’s ecommerce unit sales vs. used car sales at KMX).

Vroom Has Begun To Focus On SG&A

To management’s credit, they appear to realize the issue with the high cost structure and have announced a realignment plan:

The Realignment Plan initially included a headcount reduction of approximately 270 positions and the closing of the New York City, Detroit and Sell Us Your Car® center facilities. Since announcement of the Realignment Plan, the Company streamlined TDA’s operations and closed its service center. The service center is being repurposed to replace the reconditioning facility in Stafford, Texas. The Company also further reduced headcount by an additional 67 positions related to its proprietary reconditioning operations to align with unit volume.

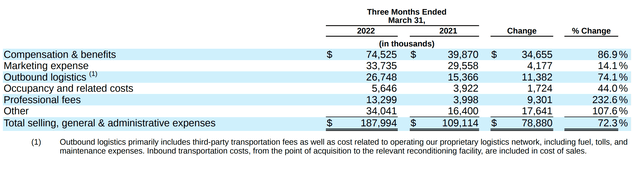

However, if we compare the Q1/2022 SG&A (Figure 12 below) to the Q2/2022 SG&A (Figure 10 above), we see that the majority of the $35 million savings has come from lower marketing expenses ($21.1 million vs. $33.7 million QoQ), outbound logistics cost ($8.1 million vs. 26.7 million), and professional fees ($6.8 million vs. $13.3 million). Marketing and outbound logistics are tied to lower unit volumes (lower marketing drive less sales which drive less outbound logistics costs). Professional fees is probably because Vroom made the UACC acquisition last quarter. The sum of the savings from these three line items was $37.7 million.

Actual savings on compensation & benefits was only $5.6 million, and is more than offset by Other + Software & IT which increased by $8.2 million.

Figure 12 – Vroom Q1/2022 SG&A (Vroom Q1/2022 10Q report)

Until we see drastically lower unit costs (i.e., compensation cost per vehicle ~$1,500), it is hard to get excited about the Vroom business model.

Upside Risk To Vroom

What can change my mind? As I’ve highlighted above, Vroom’s current business cost structure is not aligned with its volumes. With a per unit compensation expense ~$7,500, it simply cannot make money. What Vroom need is some way to expand volumes 4 to 5-fold, without additional SG&A. At 50k ecommerce units @ $3,600 gross margin, Vroom should generate ~$180 million in gross profits, which could offset an estimated ~$180 million in SG&A (note, SG&A will have to climb because outbound transportation costs scale with volumes).

It is unclear to me how Vroom can achieve that level of scale without additional marketing expense and / or regional hubs (to lower transportation costs).

Vroom currently has $533 million in cash and $154 million in restricted cash. In the first half of 2022, it burned through $138 million in operation cash flow. So, judging by the cash burn, Vroom has 18-24 months of run-way to get to that breakeven level of sales. Otherwise, the company may need to raise additional capital.

Conclusion

In conclusion, while Vroom’s low stock price may appear to be a steal, based upon the latest quarterly results, there is still no evidence the Vroom management team has turned the business into profitability. The biggest issue seems to be the inherent cost structure in Vroom’s business model, as it spends multiples of peer compensation per vehicle sold, despite not having brick and mortar locations. Being centralized also handicaps Vroom versus conventional used car dealers, as it has to incur a lot of transportation costs, which can run into hundreds of dollars per vehicle.

I estimate the company can operate in the current model for another 18-24 months before it runs out of cash. Until the margin picture changes, I don’t see any reason why investors should get involved with Vroom.

Be the first to comment