gesrey

By Garrett Baldwin

Consider the following: Andrew Brigden, Chief Economist at Fathom Consulting, found that 469 international economic downturns occurred between 1988 and 2020. Of those events, the International Monetary Fund had predicted only four.

When it comes to forecasting the likelihood of a soft or hard landing by late 2023, it’s anyone’s guess. In a world where political and economic leaders no longer agree on a simple definition of a “recession,” what chance do they have of accurately predicting crisis or recovery?

The central bank must attempt a soft landing through aggressive rate policy and old-fashioned luck as inflation pressures continue. In addition, several new risk factors – foreign to previous inflationary cycles – could further entrench inflation and create even more uncertainty.

Mixed signals

In August, markets rallied on low volume after the Commerce Department reported an 8.5% annual increase in the Consumer Price Index (CPI). Core CPI – a measurement stripping volatile food and energy costs from the equation – registered at 5.9%.

Month-over-month, core CPI was flat but still elevated.

The White House took a victory lap in response to the data, with President Joe Biden telling Americans there was “zero inflation” in July. Half-truths and new definitions for basic economic terms have become pastimes among officials. Despite two consecutive quarters of GDP contraction (a common measurement of past recessions) earlier this year, Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell and National Economic Council Director Brian Deese both argued that the U.S. economy did not fall into recession. Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen and Nobel laureate economist Paul Krugman were counted among the many who agreed.

An argument over the definition of a recession erupted in online portals. Wikipedia permitted the removal of “two straight quarters of economic contraction” from its definition. The website later locked the page to prevent revision. Facebook and Instagram now flag discussions around recession that don’t fit the official narrative. That said, Deese had used the “two quarters” definition on television for over a decade. So, too, have many recession-denying officials.

These semantics matter. Even though the National Bureau of Economic Research will decide whether the U.S. economy fell into recession this year, it’s important to note that an official recession has been declared 10 consecutive times that the economy experienced negative economic growth in two straight quarters. But the odds of an announced recession before the election are 0% likely. Even if the U.S. isn’t in recession, the likelihood increases as the Federal Reserve must take action to tame ugly inflation numbers.

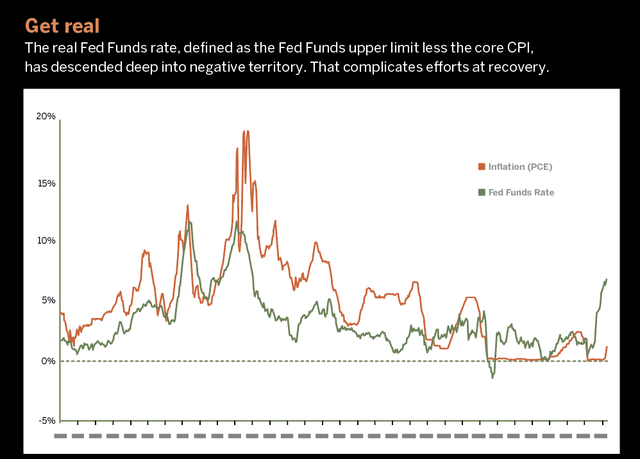

With the CPI reaching 8.5% in July, the real U.S. interest rate (based on the Fed Funds rate of 2.5%) is negative 6%.

That’s the lowest level on record and draws comparisons with the inflationary cycle of the 1970s. While many pundits believe inflation will cool over the next eight to 12 months, the transitory narrative never materialized, and new factors linked to wages and global supply chains have emerged.

Hedge fund manager Bill Ackman has suggested the Fed may need to increase the Fed funds rate to 5% in 2023 to contain entrenched inflation and wages. Ackman has indicated the market failed to price in such risk. Zoltan Pozsar, global head of short-term interest rate strategy at Credit Suisse, thinks a 6% Fed and an “L-shaped recovery” may be necessary to fix structural problems.

Venture capital manager Chamath Palihapitiya has noted during several episodes of the All-In podcast that the U.S. has never tamed inflation after consecutive prints of CPI over 5% without bringing the Fed Funds rate above that level.

George Washington University professor and former U.S. Transportation Department Deputy Assistant Secretary Diana Furchtgott-Roth expressed similar concerns in June. “The Fed is projected to end the year at a Federal Funds rate of 3.25% – well below inflation,” she said. “Inflation has never been reduced with a Federal Funds rate lower than the inflation rate.”

The markets don’t believe such hikes are coming. In fact, investors have priced in rate cuts by the first quarter of 2023. The bet is the Fed will flinch and move to support the economy.

Interest rate hikes above 5% could create problems for Washington, including higher borrowing costs at the Treasury when U.S. debt is north of $30 trillion. However, the Fed’s historic and aggressive moves on rate hikes have preceded other challenges at home and in the global economy. The higher the rate hikes go, the less soft the landing will be, even if such actions are necessary to prevent stagflation.

Aside from the observations of analysts Palihapitiya and Furchtgott-Roth, other challenges complicate the mid-to-long-term inflation picture, including warnings from the 1970s.

Not much help from Congress

There are three primary ways to combat inflation.

The first is through supply-side solutions. More products and services could bring the supply and demand imbalance into better equilibrium. Congressional or regulatory agency policy can promote these approaches. While Congress provided stimulus to enhance semiconductor production, the White House policies could limit U.S. oil and gas development. For example, the White House raised oil royalty rates for the first time ever in 2022 and scaled back lease sales.

It will also take time to expand supplies in various U.S. industries online. Today, the global semiconductor supply chain remains under pressure as concern grows over China’s possible invasion of Taiwan. Such an event could destabilize roughly 90% of the worldwide semiconductor supply.

The second pathway is through fiscal policy. The recent passage of the Inflation Reduction Act raises corporate taxes, which could cause companies to pass along the expense by raising prices for consumers. In addition, Congress has again engaged in massive fiscal stimulus when inflation remains high. The Inflation Reduction Act will likely fail to live up to its name.

The Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania assessed the legislation this way: “The act would have no meaningful effect on inflation in the near term but would reduce inflation by around 0.1 percentage points by the middle of the first decade.”

Finally, the Federal Reserve’s monetary policy is the bluntest tool against inflation.

The central bank’s rate hikes increase the cost of capital, change consumer spending and affect the “aggregate demand” of the U.S. economy. When the Fed is forced to go it alone, especially with limited supply-side and fiscal policies, it could require a level of aggressiveness that stymies consumer spending on housing and other durable goods – the critical drivers of macroeconomic growth, according to Eric Basmajian at EPB Macro, a company that provides economic research.

As Basmajian notes, these two components of the U.S. economy comprise less than 15% of GDP today but are the primary factors in deciding whether the U.S. economy swings between recessionary and expansionary periods.

Deglobalization and realignment

Domestic prices remain stubbornly high.

The July jobs report showed robust employment has been anchored by a 5.2% increase in hourly wages.

That said, real wages remain lower than inflation, and the bulk of wage gains have been driven by individuals switching jobs. According to Pew Research, Americans who changed careers have earned a median 9.7% pay increase since 2020 while the median for employees who remained with the same employer was a 1.7% loss. With more job openings in America than individuals seeking jobs, observers expect wages to continue to rise, fueling further inflation as costs are passed on to customers.

The Russia-Ukraine war has fractured global supply flows in critical commodities, adding to supply chain problems lingering from the COVID-19 shutdowns. Both events are contributing to a continued shift toward deglobalization.

“If the trend toward deglobalization continues, it could cause a supply-side shock,” writes Oleg Ruban, Head of Analytics Applied Research for Asia Pacific at Morgan Stanley Capital International. “In addition to shortages, the lack of global competition and a long-term reduction in trade could add to inflation pressure, as well as slower innovation cycles and lower long-term GDP growth.”

For decades, multinational companies have lowered the cost of labor by outsourcing manufacturing and other business lines to developing nations.

During the period of globalization, the international workforce doubled in size. But the United States must now onshore critical supply chains in semiconductors, pharmaceuticals and other industries that have relied on foreign labor and expertise. Palihapitiya argues that while onshoring will benefit national security, companies will face challenges in controlling wages. That’s especially true if job openings increase, causing more workers to look for higher pay.

What’s more, the onshoring movement is transpiring during the most significant global realignment of the nations’ political and economic interests since World War II, a trend that’s not inspiring much media coverage.

Since 2009, Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa (BRICS) have moved toward greater collaboration and closer political alliance. Recently, the BRICS began negotiations with Argentina and Iran about further cooperation on trade and less reliance on the U.S. These seven nations – all engaged in a large amount of physical resource extraction and trade – represent more than 31% of the global GDP and 42% of the world’s population.

In addition, the political alignment has given rise to rumors that these nations may explore a new currency for global trade. That could threaten the dollar’s strength in worldwide business and create new inflationary challenges.

Bloomberg’s three-act play

As noted, the blunt nature of the Fed’s rate hikes will increase the cost of borrowing and may aggregate demand for durable goods. American consumers have opened a record number of credit card accounts, hinting at a cost-of-living crisis and the possibility of a credit bubble in 2023.

Meanwhile, the 2022 surge in gasoline prices presents an extremely critical challenge for the Federal Reserve as it raises and cuts interest rates. Gasoline prices have slumped since June, which is linked to a sharp drop in demand. The total demand for gasoline in the U.S. in the summer of 2022 was lower than the demand for fuel during the height of COVID lockdowns in the summer of 2020. At the same time, China’s demand has slumped because of ongoing lockdowns.

The fuel equation could change in October. By then, the White House is expected to end its policy of releasing 1 million barrels daily from the Strategic Petroleum Reserve.

With aggregate demand under pressure in the gasoline markets, investors may want to examine other possible sectors facing supply challenges. Crushing aggregate demand with limited supply support can reintroduce inflationary pressures if the Federal Reserve starts to cut interest rates again. If supply is flat and demand increases again, one should expect higher prices and a possible repeat of an inflationary cycle linked to energy.

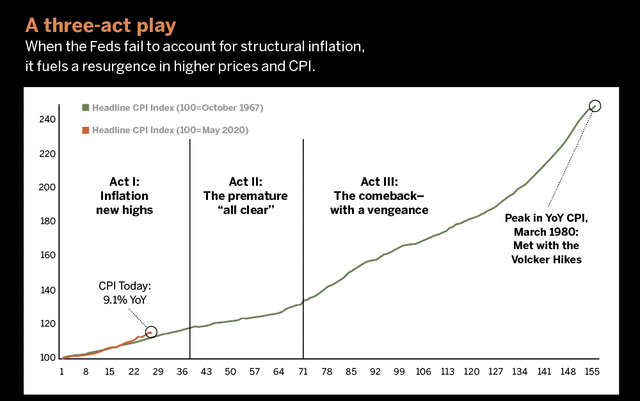

This was a critical challenge for the Federal Reserve and its Chairperson Arthur Burns in the 1970s, as it struggled to contain long-term inflationary pressures. Simon White, a commentator at Bloomberg Markets Live, notes that conditions in today’s economy could follow a similar inflationary trajectory.

White projects a similar “three-act play” with the Fed failing to account for structural inflation that fuels a resurgence in higher prices and CPI.

“We are now in Act I, where inflation is high and rising,” writes White. “We will soon enter Act II, where a respite in inflation hoodwinks the Fed into believing it can prematurely take its foot off the tightening pedal prematurely. This sets the stage for Act III, where price growth stops falling and takes off again, this time making new highs.”

The central bank finally met the challenge until former Fed Chair Paul Volcker raised interest rates above the CPI. While the economy fell into a recession in the early 1980s, a combination of supply-side policy efforts helped restore economic confidence and investment.

However, this time is different. The destabilizing nature of deglobalization, record government debt and inflationary costs linked to the green transition creates unknowns that make relying on Fed policy alone a questionable approach.

Soft landing or stagflation

Can the Federal Reserve achieve a soft landing? Has there ever really been one? It depends upon whom one asks, but a June 2022 report from the Congressional Research Service (CRS) noted that “soft landings are infrequent.”

The CRS also said Powell highlighted soft landings in 1965, 1984 and 1994. But economists have pointed out differences between then and now. “Some other recessions, such as in 2020, should not be attributed to tightening,” the CRS wrote. “However, inflation was low in 1965 and 1994, and below 5% in 1984.”

While the U.S. economy may avoid a recession, there’s also the issue of an interconnected global economy. What should one make of the many emerging markets facing pressures over a rising dollar?

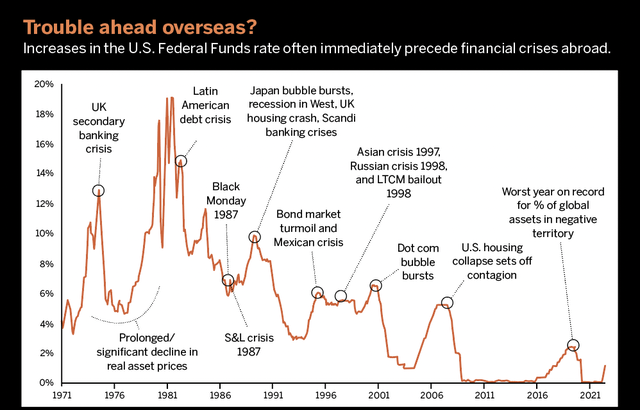

To begin to answer that question, the chart “Trouble ahead overseas,” (top right) shows the Fed’s actions on rate hikes since 1974. Every time the Fed has moved quickly on rate hikes, a global crisis has emerged not long after.

Though several crises were domestic, including Black Monday, the Great Recession and 2018’s market tantrum, one can’t help but notice the relationship between sharp rate hikes and global events like the Asian financial crisis, the Latin American debt crisis of the early 1980s and the Long-Term Capital Management bailout.

In 1994, the Fed might have achieved a soft landing, but rate hikes helped fuel a collapse in the Mexican peso and the ensuing Tequila Crisis. These days, nations like Sri Lanka and Bangladesh have already experienced severe financial challenges because of rising debt.

But the possible global contagion isn’t limited to one or two nations in the months or years ahead. The International Monetary Fund has warned that dozens of countries face debt pressures from a rising dollar.

The known challenges carry steep risk. But the unknowns could produce additional pressure that may force central banks to pivot and potentially commit a series of policy errors. The global economy is in uncharted waters, but the range of possible responses seems the same as in the 1970s.

The lost decade

Even in the face of rising inflation, the so-called “hedge” assets like gold and bitcoin have underperformed in 2022. A stronger U.S. dollar and little concern about debt insolvency have put pressure on these assets and engendered broader bearish sentiment.

That said, investors who aren’t actively trading the ups and downs of the market should consider using a playbook from the past to confront the uncertainty of the Fed’s interest rate plan. As noted, the Fed’s failure to tame inflation in the 1970s suggests potential challenges may lie ahead.

Investors should revisit assets in the oil-and-gas patch, particularly exploration and production companies like Devon Energy (DVN) and ConocoPhillips (COP) that continue to return capital to investors in the form of higher dividends or aggressively pay down their balance sheets.

In addition, real estate investment trusts – focusing on industrial properties – will benefit from reshoring international supply chains. Names like Stag Industrial, Inc. (STAG), Duke Realty Corp. (DRE), and Prologis, Inc. (PLD) are REITs that offer protection against inflation through rising rents and strong cash flow.

In addition, the playbook includes cheap community banks and financial thrifts that may eventually become takeover targets. Inflation can strain existing deposits among institutions. Besides, the consolidation of the financial sector will remain a trend for the foreseeable future. In the public markets, dozens of community banking institutions are trading for less than their liquidation value. Buy and hold, and don’t look at them.

Be the first to comment