gesrey

Introduction

Last year, I started writing an article series about retail investor mistakes, and how I avoid them. Those articles covered the topics of “Narrative-Based Investing”, “Cycle Awareness”, and “Chasing Yield”. This article will cover a topic that I think is very timely in the current market environment: Overpaying for a stock because of the business’s “quality”.

In my marketplace service, The Cyclical Investor’s Club, I analyze about 600 stocks per quarter, and one of the benefits of looking at so many stocks individually is that sometimes I can see certain patterns emerge that other investors might not see. One of the patterns that has been in place for quite some time is that investors are paying way too much for businesses they perceive as being “high quality”. Others might refer to stocks of this type as “Blue Chip”, “SWAN”, or sleep-well-at-night investments. Usually, these are the stocks of businesses that produce goods and services that are household names, or they produce products like consumer staples or necessities like electricity and water. Because of the steady demand for these products and services investors feel will have steady and consistent returns, even during recessions. Big-name brands, dividend streaks, and steady earnings, along with some basic business quality metrics, seem to be the factors investors lean on most to describe “quality”.

That, in and of itself, isn’t necessarily a big problem. But what is a problem is that investors tend to then go one step further and assume these sorts of factors that contribute to a “quality” designation for the business also justify a higher valuation for the stock. In short, investors are willing to pay more for “quality”. Often a lot more for it. And when they do, they are making a big mistake that will nearly always produce poor returns.

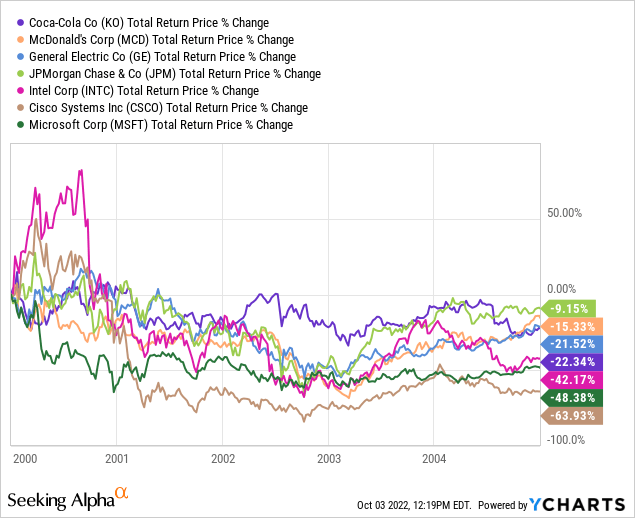

Below is a sample of the 5-year returns of 7 “quality” businesses from the year 2000 that are still around, and at least of few of them are still considered “quality”. The chart starts in 2000 when they were all overvalued using a basic PEG ratio metric and runs until 2005.

The bad returns investors get from overpaying for stocks are not always this bad. It’s also common for a stock price to simply go nowhere for a decade or more after it gets overvalued. This article will be about how to avoid returns like those above, but also how to avoid 10 years’ worth of flat, or underperforming returns as well.

Defining Quality

In order to understand my approach to “quality”, it’s best to start with the simpler example of bonds, and then apply what we learn there to stocks. If you buy a bond and hold it until maturity, your nominal return will be whatever the bond yield was when you purchased it. As I write this, the US 10-year Treasury Bond yield is +3.76%. So, if you buy one of these bonds and hold it for 10 years, then you will earn +3.76% per year on your investment, provided the US government pays its obligation. In this case, the “quality” of the bond is determined by two things, the first is the odds the US government will pay you, and the second is the inflation or deflation rate during the holding period. If we assume there is no inflation, and the US government pays up, then this is a “quality” investment. If the borrower who is issuing the bond does not pay their obligation, then it would not be a “quality” investment. In my opinion, at least in retrospect, we can very clearly define what was a “quality” bond investment (one in which you were paid back what you were owed) and a non-quality bond investment, in which you were not paid back what you were owed. If we take this basic understanding and also include inflation so that if you are paid back your money with interest and that amount is greater than inflation, then you made a “quality” investment, and if you are paid back an amount with interest that is lower than the rate of inflation it was a “non-quality” investment, we have a pretty clear understanding of a quality vs. a non-quality bond investment. And while we can always come up with more complicated examples, this basic, binary definition of “quality” I have found to be very useful in stock investing.

Warren Buffett many decades ago introduced the idea of treating stock investments as “equity bonds”. That understanding has inspired a lot of my core “full-cycle” investing approach. The simplest way to treat a stock as an equity bond is to take a stock’s earnings yield (which is the inverted P/E ratio, or E/P). So, a stock with a 20 P/E ratio would have a 5% earnings yield. You can then treat that earnings yield, just like you would treat a bond yield. The one caveat is that some businesses can be expected to grow their earnings over time, so rather than just collecting that earnings yield, the investor also gets the benefit of any growth of those earnings over time. This is one of the major benefits of holding stocks long-term rather than bonds (and why I don’t own long-term bonds). If there is inflation over the given time period, a bondholder loses purchasing power, while a good business can pass inflation on to its customers allowing earnings to grow at a rate equal to or higher than the inflation rate. So, for a “quality” business, inflation is not a serious risk to the purchasing power of the earnings because the business can pass higher costs on and earnings rise accordingly.

As I noted in the introduction, definitions and understandings of quality can vary quite a bit when it comes to businesses. I prefer to have a clearer understanding of what “quality” means to me. And my definition is fairly binary in nature. Either a business meets my quality standards, and I will consider buying it, or it does not meet my quality standards, and I will not consider buying it. There are many benefits to framing quality in such a way. The first benefit is that it helps me avoid value traps because if the basic quality standard is not met, then I will not buy the stock at any price. I don’t buy “cigar butts” or turnarounds (at least, not on purpose). The second benefit is that a stock’s measure of quality does not really mix with the valuation using this approach. Quality is one thing, and valuation is another. If an “equity bond” yields 5%, and it is “high quality”, then you can expect to get a 5% real yield over time from the investment.

So, my definition of quality is that the business has earnings that have a history of growing at a rate above average long-term inflation, which is roughly 3% or so in the United States. In addition, in order to be high quality, the business must have experienced a recessionary environment and earnings must have recovered from the recession in a timely manner. In addition to these factors, I make sure there aren’t any clear signs that the historical earnings pattern will change any time soon. Basically, if I can count on earnings per share, adjusted for buybacks and recession downturns, to grow at a mid-single digits rate or better, then I am dealing with a “high quality” business. How fast earnings are growing beyond that is irrelevant when it comes to determining quality. A business growing earnings at 5% and a business growing earnings 15% are the same quality as far as I’m concerned, all else being roughly equal.

What this definition does is strip out any brand name bias, or dividend streak bias, or fluctuation of earnings out of the equation (as long as they are not very deeply cyclical and recover in a timely manner from downturns). A utility or consumer staple business doesn’t get any extra “quality points” from me if they grow earnings at 6% every year without exception compared to a business that has more volatile earnings, but still grows cumulative earnings fine over a full economic cycle. They are both “high quality” to me. Similarly, I don’t give “brand names” any special treatment compared to a company whose brand I’ve never heard of, either. If the earnings metrics are there and look like they will continue, they are both “high-enough quality”.

So, first I look to see that the historical data is there to determine how earnings have grown in the past, then I check to make sure there isn’t some clear impediment to earnings growing similarly in the future and that the rate of earnings growth is higher than inflation. If there is reason to expect these things are true, the business is high quality enough to evaluate for a potential purchase. (Just as with a bond if you evaluated a government or corporate entity to see if it was likely they would pay you back your money with interest.)

What this quality designation boils down to is that quality businesses can 1) pass inflation onto their customers, and 2) reliably grow earnings at least a little faster than that over a full economic cycle. It’s very simple.

The mistake of mixing valuation with quality

I have shared in previous articles that the first thing every investor should do before they buy a stock is to have an acceptable rate of return in mind. Determining quality is really just a way of figuring that the accuracy of your earnings expectation is likely to be reasonably high. A quality stock won’t have negative long-term earnings growth, for example. That is literally the opposite of quality in most cases. So, if you invest in a stock with an expectation of a rate of return of 10%, if the business is of reasonable quality and your valuation method is reasonably good, the stock will produce a 10% CAGR, just as you expected (and just like a 10% yielding bond would). The fact that the business did not produce less than a 10% CAGR shows the business was of sufficient quality.

Now imagine that you take a stock with all the same earnings metrics, but because it is a well-known brand or produces some sort of consumer staple, the market has bid up the price and it now has a much higher valuation. Using the same valuation process as you used before, the expected return is now a 5% long-term CAGR instead of 10%. Because the business is indeed “high quality”, your prediction about earnings and earnings growth is correct, and the stock goes on to produce a 5% CAGR. Being “higher quality” didn’t affect your expected return. The expected return was very accurate, but it still wasn’t a very good return. You got nothing extra out of the fact that earnings were very predictable except for low predictable returns.

Historical Example: Nifty Fifty

During the late 1960s, a meme of sorts developed that ran directly counter to the lesson I’m sharing in this article. The idea was that because certain “blue chip” stocks were so high quality that they would grow their earnings at a good rate into the future, there really was no price that was too high to pay for them. Basically, any valuation was justified and most of the stocks that became known as the “Nifty Fifty” traded at P/E ratios of 50 or higher (which implies an earnings yield of 2%). The idea was that if you just bought them and held them you would get good returns over the long term because eventually earnings would catch up to the price. But the truth is that you would have had to hold for a very long time in order to get decent returns on the group.

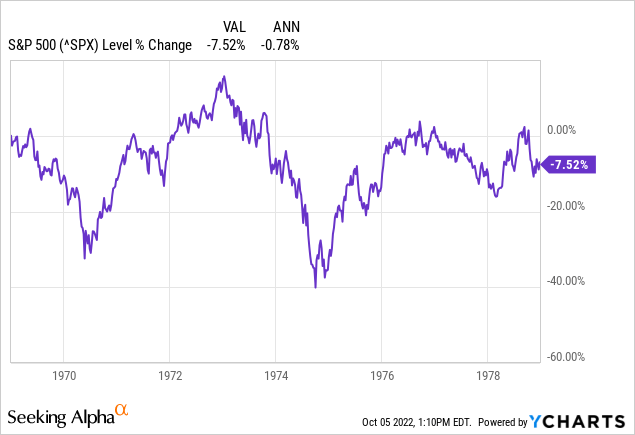

For 10 years, from 1969 to 1979 here is how the S&P 500 performed after the Nifty Fifty period in the late 1960s.

The S&P 500 returns for this decade were nominally flat, and considering inflation averaged in the high single digits during this time, in real terms, the 10-year returns were negative. The single biggest explanatory factor for this poor performance was that in 1969 valuations for stocks were far too high, and the expected returns were far too low.

Conclusion

Just like with bonds, it makes sense to define “quality” with stocks on whether or not the business’s earnings projections can be dependably met over the long term. If they can, and the business can grow earnings at a rate above inflation, then the business is high quality enough to invest in. After those conditions are met, quality doesn’t really matter anymore. It is rational once basic quality is established, to seek out valuations that will provide the biggest return for the stock investor, just as, once a bond investor knows they will get their money returned with interest it makes sense for the bond investor to seek out the bonds with the highest yields over any given time period.

The truth is, if we take a 5-year or 10-year time period, it’s relatively easy to identify “high-quality” stocks in the market today. Probably 400 out of the 500 stocks in the S&P 500 are high quality, and a decent investor could do a reasonably good job of predicting the earnings trends 5 years from now. The difficulty is maximizing one’s returns. Getting low single-digit returns over 10 years in the stock market is actually pretty easy in almost any environment. You could throw darts at a list of S&P 500 stocks and do that. But if you want to consistently do better than that, valuation is what is important once basic quality is established, and it’s buying at attractive valuations that will help an investor achieve better-than-average returns over the long term.

Be the first to comment