GibsonPictures/E+ via Getty Images

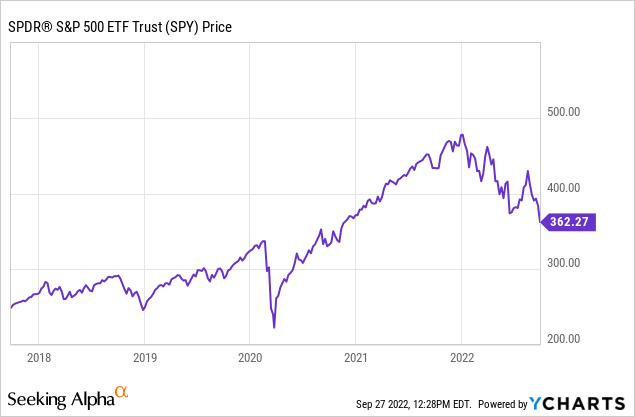

Stocks have plunged since mid-August, with the broad S&P 500 Index (NYSEARCA:SPY) closing down roughly 24% for the year as of yesterday. The selloff is widely attributed to the Fed’s ongoing battle with inflation, as cash rates push toward 4% and 30-year fixed mortgages close in on 7%. The Fed’s messaging has been clear that it will not pivot policy/cut rates in response to stock market declines, hopefully having learned from the failed half-measures of the 1970s and early 1980s. After puzzlingly huge bets came in all summer on the Fed to cut rates to zero and let inflation soar, the market seems to have sobered up, and the summer rally melted away. Now stocks are roughly in the range of their June lows, and the obvious question is what is likely to happen next.

Starting from the winter 2018 rout, the S&P went from undervalued to fairly valued (spring/summer 2019) to somewhat overvalued (late 2019/early 2020), to overvalued (2020, after recovering from the coronavirus crash), to insane (summer 2021 to early 2022). Now the dominos are falling and it’s unwinding in slow motion, likely relegating the Everything Bubble to the dustbin of history.

The S&P is the most popular index among retail investors and 401k accounts, but if its largest mega-cap tech holdings are going to take a disproportionate amount of speculative money in huge booms and busts, I think I might personally rather have small-caps (IJR) and mid-caps (IJH) as the foundation of my portfolio. Food for thought!

Why Would You Pay 50x Earnings For Mega-Cap Stocks When Cash Pays 4%?

Modern portfolio theory tells us that as rational investors we should choose investments that are capable of earning the returns we need with as little risk as possible. Alternately, we can choose how much risk to take, and maximize how much return we’ll accept from it. Modern portfolio theory catches a lot of criticism, but this point is pretty obvious – investors should judge their returns by how they do relative to risk-free Treasury bills, and shouldn’t pay big multiples to earn returns that can be had with risk-free Treasuries.

As of my writing earlier today, you can get 3.35% annually from a 3-month Treasury bill, 3.99% annually from a 6-month Treasury bill, and 4.16% annually from a 1-year Treasury bill. Or you can pay 50x expected 2023 earnings for Amazon (AMZN), and get no dividend. Amazon bulls will tell you that they can rapidly grow profits from the cloud, but lately, they’ve managed to lose a bunch of money investing in Rivian (RIVN) and didn’t make a profit this year. Elsewhere in the electric car space, Tesla (TSLA) trades for 48x 2023 earnings as well, assuming they execute perfectly.

Microsoft (MSFT) bulls will probably tell you that they can eat Amazon’s lunch in cloud computing. MSFT trades for 23x 2023 earnings estimates as well, and it’s the only company I’ve mentioned that has a higher earnings yield than the 1-year Treasury. All of these companies are competing with each other, and many of them are priced as if they’re going to take market share from competitors, when in fact it’s zero-sum, so someone has to lose market share. This means that the market at large is still overvalued. And to these points, all of these stocks’ fortunes are tied to the macroeconomic environment, whereas if you invest some money in Treasuries, you get paid back no matter what, principal plus interest (I guess unless there’s an apocalypse).

The obvious result is that big investors are not willing to pay as high of prices for stocks as they were last year now that they have an alternative.

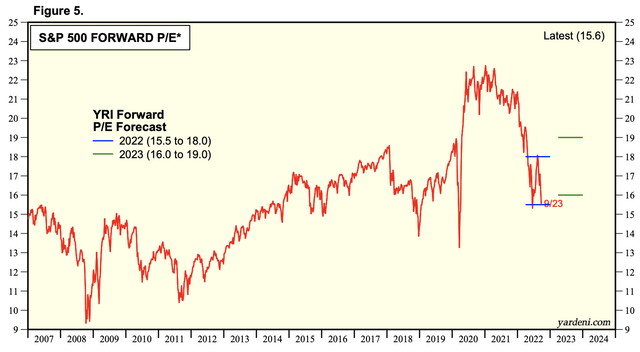

S&P 500 PE Ratio (Yardeni Research)

For stocks, multiples of 15x to 18x are considered to be consistent with long-run expected returns of 9.5% to 10.5% annually. When stocks are really cheap like they were from 2008 to 2012, you can make more, and when they’re expensive, like 2021, you generally make much less. Here’s a longer-term graph for illustration.

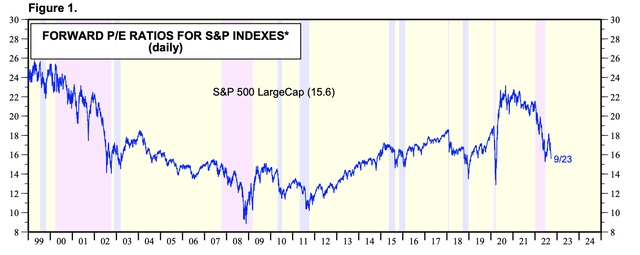

S&P 500 PE Ratios (Yardeni Research)

See how expensive stocks were in the late 1990s? That coincided with terrible long-run returns. Despite unfortunate timing, investors who bought stocks in 2007 got fair prices, leading to a quicker recovery and better long-term returns.

Solely on a P/E basis, the S&P 500 looks pretty good here at about 16x earnings, and mid-caps and small caps look better still.

However, the problem, of course, is earnings. The unsustainability and possible reversal of earnings growth is the main reason I believe that stocks are not yet a buy and that investors should wait for another 10% decline to start buying. With the momentum strongly against stocks, this seems more likely than not.

Earnings Growth Is A Structural Problem In A Rising Rate (And Rising Tax) World

2021 was the best year ever for S&P 500 corporate profits at $209 per index unit, but early 2022 blew even 2021 away. Q2 2022 (April-June) was the best quarter ever for corporate profits. Consumers who were sick of 2 years of lockdowns took went YOLO, splurging on travel, dining, and shopping. Underneath the hood, however, living standards have more or less steadily fallen since 2021 as inflation outpaces consumers’ incomes.

In my last macro piece, I highlighted a fascinating paper from the Fed. The paper showed that earnings before interest and taxes had grown at an inflation-adjusted 3.6% annually since 2004 for S&P 500 firms. However, with tax cuts and lower rates, net income grew 5.4% annually in excess of inflation (due to lower rates and lower taxes). Share prices grew even faster, at 5.9% annually in excess of inflation (inflation compounded at around 2.5% over this time).

This is a back-of-the-envelope calculation, but if you deflate S&P 500 returns by the amount that income tax cuts and interest rate decreases helped it over the past 17 years, the index would only be around 3300, rather than hitting nearly 4800 in January. Interestingly, this lines up with my own top-down valuation of the markets. And if you take projections for future earnings before interest and taxes, but turn those into a headwind rather than a tailwind, the long-run picture for earnings is bleaker still, potentially implying a fair value for stocks of the lower end of the typical 15-18x range, on top of earnings themselves being lower.

These are all structural issues with investing in stocks, but this doesn’t yet take into account what kind of cyclical downturn we could see without stimulus flooding the economy. Nor does it take into account the challenges that an unhealthy and rapidly aging population will give the economy and government. Once pandemic-era savings run out for consumers, there are not a lot of levers to pull for corporate profit growth. Keep this in mind when you see that the median earnings forecast for 2022 is roughly $224 per share, and for 2023 it’s roughly $242 per share. Before the wacky stimulus economy of 2021, the previous all-time high was $163 in 2019. These forward earnings estimates are simply not going to be hit. My best guess is that earnings for 2022 and 2023 combined will total $390 for both years (a bit below $200 per year), depending on when the recession hits with full force.

The bottom line is that when you take out all of the crazy stimulus, the unsustainable tax cuts, and declining interest rates over the last 20 years–stocks aren’t super cheap yet, even down 20%-plus for the year.

Stocks May Not Stop Falling At Fair Value: Unwinding The Bezzle

If you take a look at the historical graphs of PE ratios, you’ll notice that as a general rule, stocks don’t just fluctuate between being overvalued and fairly valued. In fact, stocks tend to crash far below their fair value in bear markets, sometimes for years.

Why is this so?

One of the most practically useful concepts in economics is called “bezzle.” Bezzle refers to the crime of embezzlement, which is unique among crimes in that the money that’s stolen temporarily exists twice. For example, if I were a mid-sized business owner and I think I made a million dollars in profit last year, but $250,000 was in fact embezzled by my controller, then the fictitious profit of us both is $1.25 million. I think I earned a million dollars, and my controller pocketed 250k. With time though, money can’t exist in two places at once, and eventually, it gets discovered. When this happens, I make $750,000 for the year because I have to write off the loss, while my corporate controller makes $0 instead of $250,000, whether from jail or on the run. When it’s discovered, our combined “income” declines twice as much as the embezzlement. Similar situations can play out in the markets.

1. Malinvestment

The year 2021 is likely to go down in history as the vintage of some of the worst investments ever. 2021 IPOs were wildly overpriced, but IPOs paled in comparison to the SPAC boom, which saw hundreds of companies go public, most without many real chances to succeed in business. The cost of capital for businesses was so low in 2021 that businesses that would never get funded in a free market saw huge inflows of cash. I had the misfortune of buying a couple of these, although I avoided most of the worst.

- Space exploration? Why not!

- Undifferentiated electric car companies? Check.

- Altcoins and NFTs? Check.

- Money losing Silicon Valley concepts with one-word names? Check.

- Cannabis and gambling? Check (although here some good businesses came public at inflated prices and with bad capital stacks).

The whole name of the game was that revenue growth mattered above all, and making profits was unimportant in most cases because endless amounts of money could be borrowed for free or raised as equity at huge multiples of sales. Crazy companies like this are thankfully excluded from the S&P indices (you have to make money to be included), but they take up space in investor portfolios. So what do you think investors are going to tap for cash now that their SPACs are busted? They’ll tap their index funds. And speaking of index funds, wealth managers who get paid as a percentage of AUM (1% for most financial advisors, but 2% and 20% of profits for hedge funds) had been making outsized profits for years based on inflated market values–and these are now quickly reversing.

A lot of investors won big in 2021. A lot of these same investors turned around and lost big in 2022. They paid hundreds of billions in capital gains taxes more than usual to the US government, but because of the way the tax system works they won’t be getting refunds because the losses are mostly in subsequent years.

Malinvestment pervaded deeply into the economy, not only as unprofitable companies joined the bacchanalia, but also as low-interest rates encouraged all kinds of consumer spending and borrowing. If your home’s value in Austin, Texas, is up $250k in one year, why not take out a HELOC to buy a new boat and a couple of F-150s? Why not get a $5,000 Loro Piana coat? Or pay $1,500 for a flight to Miami to party for the weekend?

The US population has barely grown since COVID, but we’ve started construction on millions of houses, many of them with shoddy construction due to 2021 supply chain issues. Who’s going to buy these millions of houses at the 7% free market rate rather than the heavily subsidized 3% rate? Good question.

This is just the stuff we know about. Chances are that the next Enron and the next Madoff are still lurking out there, waiting to be revealed when liquidity falls low enough that they can’t sustain their tricks. My guess is that maybe 5% of the top 100 companies in America and globally will be exposed as frauds – we don’t know who yet, but this happens in every severe downturn. And I wouldn’t be surprised to see Interpol working overtime trying to catch more crypto fugitives who allegedly have run away with investor money.

2. The Early Retirement Boom

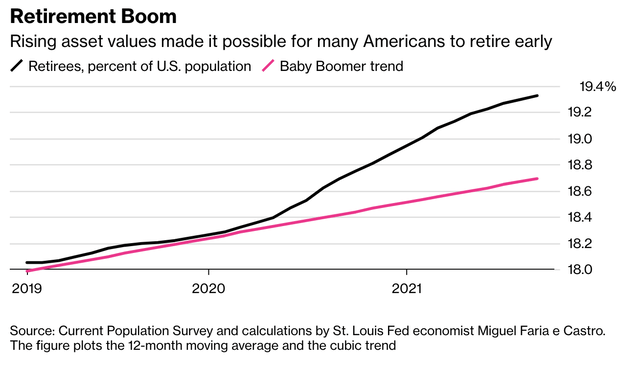

Well, for one, about 3 million extra people looked at their net worth during COVID and decided they’d had enough of working. There’s nothing wrong with this sentiment, but the timing ended up being very poor with stocks plunging in 2022.

Sequence of returns risk is a cruel mistress.

Bloomberg

But what happens if stocks fall 40% from where they retired, or even 50% like they did in 2000-2002 or 2008? Millions of people who were induced to retire by high asset prices would then be forced to repeatedly sell into a market rout to pay living expenses. It’s not clear what will happen going forward, but the risk is that a lot of decently affluent people could see their retirement accounts gradually go to zero by virtue of being overleveraged and underfunded. Retirees, as a general rule, are forced sellers of stocks, and there are a lot more of them now than there used to be. These 3 million freshly-minted retirees are going to put continual downward pressure on assets if they stay retired. Otherwise, the only other way they can get money to live is to go back to work.

3. Overleverage

Low-interest rates encouraged people to take on all kinds of leverage. This isn’t a sin, and borrowing money to make smart long-term investments is a sound strategy. The trouble happens when leverage and malinvestment interact, or when the macro environment turns so decisively that you get stuck in a bad situation.

Companies that issued junk bonds in 2021 got away with murder with the rates they’re paying vs. the risk they’re imposing, but what happens in two to three years when these bonds need to be rolled over? There are going to be a lot of zombie companies that will go out of business then in 2023 and 2024.

And of course, there’s margin debt, which at last count stood a little under $700 billion. It’s not huge compared with the value of stocks, peaking at around 2% of total market value earlier this year, but it’s a potential source of forced selling as stocks go lower.

The pandemic housing boom encouraged people to buy large homes far out from the city center. But what happens when the electricity bill doubles for that house? If the buyers needed both spouses’ income to qualify, what happens if one spouse loses their job? This is two times as likely as a single person losing their job, turning having a dual income from a source of strength into a source of weakness. This is operating leverage, another non-obvious form of leverage.

Did banks make a lot of bad loans in 2021 and early 2022? If home prices are down 5%-10% already since May in dozens of markets, and a lot of down payments are only 10% to begin with, then that’s a problem for that vintage of loans. Grant it, the 2019 loans are looking good due to now huge equity cushions and low payments, but my feeling is that the housing market will come back into balance– i.e. crash, as millions of completed homes flood the market without the demand to support them.

Where The S&P 500 Is Likely Headed Next

The momentum for the stock market is down. Many buyers are rightly choosing to earn 4% in cash rather than roll the dice on stocks, and the unwinding of overleverage and malinvestment means that a lot of people are likely to continue to sell into a declining market because they have to.

So when will buyers step in? Despite large-cap stocks trading for less than 16x earnings now, stocks are still a little high based on the stiff headwinds facing earnings over the next few years. It’s very likely that big institutional investors have run numbers similar to what we’ve run here, meaning that they’ll start to buy around 3300 on the S&P 500.

Even so, the amount of structurally forced sellers means that markets likely won’t bottom right at fair value, but rather somewhat lower. If I had to guess, the S&P 500 will bottom somewhere around 2800 sometime in the spring, but will subsequently bounce back above 3000 by year-end. 3300 is fair value – we can make an effort to handicap the amount of forced selling or capital deprivation that will happen in 2023, but if you can buy assets at good prices you should steadily do so, even if they may drop a little more in price.

2800 is purely a guess, but it’s informed by history. 2800 would put us around the level where stocks were at in the summer of 2019 when the craziness started in terms of valuations, so while it’s down a lot in price, it really isn’t that far back in time. With tighter money, the conditions will slowly be set for growth in the real economy as capital and labor get pulled away from speculative businesses and towards areas of growth like automation, sustainable energy, and other productivity-enhancing technology.

Key Takeaways

- The Everything Bubble has burst. Most people will go about their daily lives not knowing or caring, but if you’re an investor, it’s hard to tune out. Unfortunately, if you overpaid for something in 2021 (I did this a few times on stocks), there’s not much you can do about it now besides wait it out.

- The market has a lot of momentum going against it and the S&P 500 still trades above my fair value estimate of around 3300. I would wait for some more declines to start heavily buying. In the meantime, you can earn 3-4% on cash.

- Stocks still have some structural issues, but paying a lower price will adequately compensate you in the long run for the risk you take by buying them.

- Investors should review their portfolios for opportunities to lock in tax losses at current prices. Correlation tables are very helpful in this case and can help investors defer tax while still maintaining desired exposure to stocks. If in doubt, consult your CPA.

- Once stocks arrive at fair value, the best buys are likely to be small-cap US (IJR), mid-cap US (IJH), preferred stocks (PFFD), international small cap (SCZ), international (VEA), international high dividend (VYMI). For a higher octane strategy for investors with long time horizons, there are some nice leveraged plays like 90 stocks/60 bonds (NTSX), and 100 stocks/100 bonds (PSLDX). I also like leveraged Treasury funds (TYA) if rates keep moving up. You can start buying some of these now–but pace yourself and leave some dry powder.

- There also will be some opportunities to pick up blue-chip growth stocks like Microsoft and Google (GOOG) (GOOGL) if they’re hit hard by ETF selling.

- Just because you buy assets below fair value doesn’t mean that they won’t go down more on momentum. For this reason, I wouldn’t recommend that anyone go all-in based on the market hitting a certain price target unless prices were to truly crash. To these points, dollar-cost averaging is a sound strategy in high volatility/falling markets.

Be the first to comment