Carl Court

In nearly three decades as a public company, SoftBank Group (OTCPK:SFTBF) (OTCPK:SFTBY) has veered between exhilarating highs and excruciating lows, often the epitome of investment success and excess. The Japanese conglomerate’s fortunes have risen and fallen with the stock market and, for the most part, one sector in particular — digital technology. After years of explosive growth, tech investing is going through a downturn, and SoftBank with it.

The founder and chief executive Son Masayoshi, who still enjoys a cult following, believes the slump is transient, drawing parallels to turnarounds he had orchestrated the previous two times, after the dotcom crash and the global financial crisis. There are risks to this thesis: prolonged macroeconomic weakness in the wake of interest rate hikes, declining financial health and the growing scale of investor disillusionment.

The problems feed into each other and stem from financial profligacies of the distant and more recent past. Mr. Son got into the habit of overpaying for overseas ventures, as would other Japanese buyout barons, very early on. The scale and ambition have compounded over time. SoftBank’s present-day focus on information technology was cemented by a gargantuan $100bn Vision Fund. That same year, in 2017, Mr. Son made an ill-fated bet on WeWork (WE). Previously accumulated stakes in tech startups (such as Brain Corp and OneWeb), ride-sharing firms (Uber (UBER), DiDi (DIDI), Ola) and fintech companies (SoFi (SOFI), Paytm) also moved into the fund.

Thus the oft-heard criticism that SoftBank inflates tech valuations by drowning young companies with too much money. In theory, it would not matter to the group’s own investors as long as the investees were generating returns, but they have been struggling. SoftBank’s Vision Funds (including the second, more modest iteration) have been reporting back-to-back losses, totalling negative $50bn in the last three quarters, first due to crashing share prices of portfolio companies and, increasingly, declining valuations of private companies which have followed suit. The funds are unlikely to see the bottom anytime soon.

Even the pandemic blow which forced Mr. Son into divestments did not truly reduce his appetite for spending. By the end of September 2020, SoftBank cashed out $53bn, owing to a partial unloading of shares in Alibaba (BABA) and some unprofitable upstarts like SoFi, Uber and Opendoor (OPEN). One-third of the money went to share repurchases, only half as much into critical debt management and an equivalent sum into “growth investments”. Part of the latter was Northstar, an internal hedge fund tasked with buying shares in publicly listed tech stars. The new strategy, unconventional for the group, backfired: the loss-making manager wound down positions from $17bn in 2020 to $1bn in 2021 to nil this year.

Waning health and wealth

Such recklessness is problematic. SoftBank has always been laden with debt, not least thanks to Mr. Son’s proclivity for big risk-taking. Currently, its net debt to equity is close to a high 140% and barely covered by operating cash flow. Internally, however, the group uses another indicator, loan-to-value, with the equity value of holdings in the denominator. That is supposed to be kept below 25%; the other safety mechanism is keeping enough cash on hand, which right now comfortably exceeds bond repayments due over the next two years.

These policies had motivated the asset sales and a bit more discipline with Vision Fund 2. Within six months from end-March 2022, net debt shrank by close to 60% to ¥2.96 trillion, which brought LTV to 15%. Many, however, are unconvinced about SoftBank’s reported leverage numbers; this trader, for one, thinks the real LTV is almost four times as high.

Prompted by a record loss of ¥3.16 trillion posted in the earlier quarter, Mr. Son has been cutting not only debt but also headcount starting with 30% of staff at the Vision Fund. But he is not altogether axing investments, and there has even been talk of a third Vision Fund. It should not materialize, since by setting up another fund Mr. Son would be backtracking on his promise to get serious about austerity.

For now, SoftBank has avoided the immediate danger of implosion, but more fundamental changes to the balance sheet and the managerial culture could do wonders for the firm and maybe even its stock.

Shareholder woes

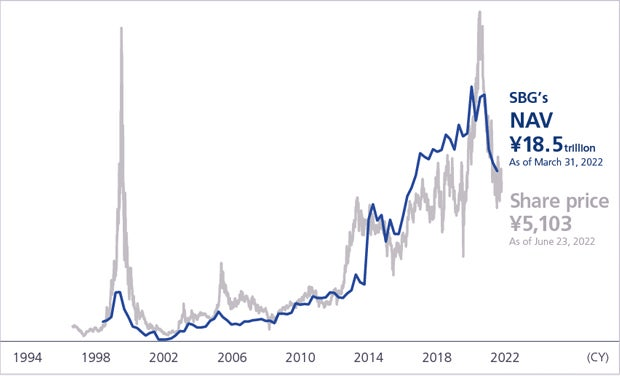

The market has not been kind to SoftBank, whose shares traded at a discount to book value as well as net asset value all the way from Alibaba’s IPO in 2014 through to the post-pandemic boom. NAV as a measure of the group’s equity holdings sans net debt is highly subjective. But the current market capitalization of ¥7 trillion renders meaningless holdings in even straightforward, profitable businesses such as SoftBank Mobile and Arm.

SoftBank’s NAV stood at ¥16.7 trillion ($116bn) as of end-September; ¥19.7 trillion ($136bn) was the portfolio value. Valuations have come down significantly from a peak in February 2021; since then, SFTBY has lost 58%.

SoftBank

Arm in arm

Mr. Son remains as convinced of his vision for the group as ever. At this point, his hopes rest on windfall profits from whatever the future holds for Arm and not so much returns from the Vision Funds. And perhaps rightfully so. Expected sometime next year, the IPO may raise up to $60bn — which falls somewhere in-between the range that the failed deal with Nvidia was supposed to fetch. More realistically, the figure could fall below $20bn. Mr. Son is determined to supersize the company regardless. So much so, he has opted out of future investor relations events, pledging to dedicate all of his time on Arm’s “forthcoming explosive growth”.

Looking forward and backward

The group’s latest financial results showed a marked improvement in the bottom line: a net profit of ¥3.03 trillion, the first positive result in three quarters. This was made possible by a disposal gain of ¥4.6 trillion from paring the stake in Alibaba from 24% to 15%. The Vision Funds though continue to bleed red ink. Among the losing trades this time is a very public failure of crypto exchange FTX (FTT-USD) that will be written down to zero, although the commitment was less than $100m, small considering the funds’ collective size and original extravagance. (Recall the $18.5bn poured into WeWork or $2bn wasted on Katerra, a construction tech startup.)

Today, the fund is no longer profligate. Nor is the group that has avowed once again to cut costs and refocus on its portfolio as is. Still, the expectation is that the Vision Funds will continue falling as more public and even more private investees run dry. The financial health and the stock price will move synchronously.

Mr. Son’s newest obsession is Arm. He will be pushing it to succeed, whatever the cost. But beyond that, it remains to be seen if he is able to turn the group around yet another time. And this time not on the back of a tech-fuelled market craze but solid financial management, due diligence and governance. Until then, I would think the strategy is to play for time and watch for signs of genuine change.

Be the first to comment