Mario Tama/Getty Images News

Find the valuation model for this article here: Samsung_DCF.xlsx

INTRODUCTION

As you have probably read, a recent 13F from Berkshire Hathaway unveiled that Berkshire Hathaway has taken a ~$4B stake in TSMC. This was a surprise to many, given that value investors have historically avoided investments in tech companies, historically speaking. This is notoriously true in the case of Warren Buffett.

So why did Warren Buffett invest in TSMC? And should he have instead invested in Samsung? Is Buffett now a growth investor?

In this article we will unpack the dramatic secular changes that are happening in the semiconductor industry. At the end of the article, you will find a valuation model for Samsung that I created a few months ago. The data has not been updated, but you may find it interesting.

VALUE INVESTING: A PHILOSOPHY OF ? AND ?

In the contemporary market, “technology” (or its euphemism, “growth”) and “value” are often presented as a dichotomy of investment strategies. This over-simplification reflects the fact that value investing was invented at a time when value had yet to be conceptualized, and ignorant of the fact that the concept of value investing was perfected during the late stages of the industrial revolution; I often ask myself how the de-industrialization of the U.S. might have skewed the results.

In recent times, the skew has become more pronounced. Someone searching for a strong tangible book value likely missed the power of platforms and network effects. Buffett effectively admitted this in 2017.

To put it straight, what Graham and Dodd would call “value investing” is what we would call “due diligence” today. What we would call investing in “value” today consists largely of investing in companies that trade at low multiples, often through a diversified portfolio, occasionally targeting specific sectors, and most importantly avoiding investments in “tech”. While deriving intrinsic value from cash flows and assets is more immutable, clearly the philosophy of “value” is tangible—subject to change.

Highly cyclical and fraught with execution risk, the semiconductor industry might seem like an odd place to look for “value”. After all, semiconductors have had a good run in the past few years. I cannot precisely define “value investing”, but it is a certainty that when prices expand, expected return contracts. The high operating leverage (in the industry this is known as “fill the fabs”) has made semiconductors a challenging business. Or has it?

Not in the aggregate sense, which puts veracity to claims that we are now in a post-post-industrial era. The Philadelphia Semiconductor Index (SOX) has seen free cash flow grow at 25% per year for nearly the last 20 years. Revenue has grown over 11% per year, for 20 years… 16~19% per year in the last 5 years alone. The SOX has crushed the S&P, outperforming it by about 381% over the last ten years, and 74% over the last five. This was very volatile for a portfolio of 40 companies (a S&P500-relative β of 1.38), but came with far less execution risk than holding any single stock in the index.

WINTEL WARS: TSMC STRIKES BACK

Semiconductors are the building blocks of modern technology, the refineries to our digital gold. As a general rule, we are limited by the power of our hardware. As better hardware becomes available, exponentially more powerful software becomes possible. The utility of this software plateaus, until it reaches the threshold required for new use-cases. Today, this seems most apparent in the emergence of artificial intelligence use cases, and the ability for smartphones to do rendering tasks that would have required a desktop unit just a few years ago.

It also seems that software progresses at least as fast as hardware does, at least in some domains. Computer scientist Martin Grötschel analyzed the speed with which a standard optimization problem could be solved over the period 1988-2003. He documented a 43 millionfold improvement, which he broke down into two factors: faster processors and better algorithms embedded in software. Processor speeds improved by a factor of 1,000, but these gains were dwarfed by the algorithms, which got 43,000 times better over the same period.

-Andrew McAfee & Erik Brynjolfsson, Race Against the Machine

Historically, Intel has dominated the semiconductor industry. Microsoft’s Windows OS was designed to run on Intel’s X86 instruction set architecture, effectively creating a cartel. Intel also led the industry in terms of manufacturing technology. Intel could fit more logic gates into a single chip, meaning that Intel’s chips were simply more powerful (holding chip dimensions constant). Even as the manufacturing technology available to competitors advanced, Intel was always several steps ahead.

The technical complexity of the relationship between Intel’s hardware and Microsoft’s software has masked the significance of the X86-based “Microsoft-Intel Cartel”. In order to compete, companies such as Nvidia had to have better designs that made up for their disadvantages in manufacturing (which was outsourced to TSMC, in the case of Nvidia). In the CPU market, they would be incompatible, with the notable exception of AMD’s X86 license.

A profound and historic shift is happening, one that will reshape the industry in ways that are difficult to predict today. Leveraging the rise of the smartphone, both Samsung and TSMC have caught up to, and exceeded, Intel’s manufacturing technology. ARM has risen as a viable alternative to X86, also riding the rise of the smartphone. The ramifications are likely to reverberate well beyond semiconductors, into many different aspects of “tech”.

It’s super important for the US House and Senate to finish the CHIPS Act. Just get that freakin’ thing done.

-Pat Gelsinger, Intel CEO (source)

To put it charitably, Intel blew money on buybacks and dividends while TSMC and Samsung slowly caught up. Over the last decade, Intel has spent approximately $106B on buybacks and dividends, and $126B on R&D. The situation is so desperate that Intel had to beg the government for help, then partner with TSMC because its manufacturing is so far behind that it cannot even compete in areas that require the latest performance standards. The CEO of Intel recently visited Samsung leadership in Seoul.

Intel’s lobbying and PR campaigns have been effective; there are many investors who firmly believe that Intel is deep in “value territory” and that it is only matter of time before it regains industry leadership. This is unlikely to happen. The annals of the semiconductor industry are filled with those who lagged behind and never caught up. The number of leading fabs has shrunk from 10-15 in the early 2000s, to just two today (Samsung and TSMC).

The fall of Intel (and the rise of Samsung/TSMC/ARM) is creating a massive secular shift that will reverberate across many companies in tech-related industries (and even geopolitics). Companies that were formerly at a manufacturing disadvantage now have both superior designs and access to the best manufacturing technology, compared to the vertically integrated Intel.

TSMC and Samsung, which manufacture chips on behalf of other customers, have built powerful partnership ecosystems around tight collaboration with customers. The economics will be difficult for Intel to compete with, as they are able to see trends and issues arising much faster. Manufacturing engineers work so closely with the design engineers of customers, that they are often collocated in the same office.

The entire ecosystem leverages the R&D of each constituent, mostly designed using ARM’s instruction set architecture. In order for Intel to keep up, it will need to compete with the R&D of the entire ecosystem. Not just ARM, but TSMC and Samsung, plus all of their partners.

But why has chip demand increased so rapidly? Most people are aware that chips move in relation to Moore’s Law, meaning that the chip density doubles about every two years. Holding all else equal, this translates to a doubling of performance.

Yet in recent years, the performance gains have significantly exceeded this benchmark. Improvements in the chip architectures themselves, mainly the tailoring of chip designs to specific purposes (ASICs), have led to performance leaps equivalent to decades of Moore’s Law in a handful of years. The ability for any upstart to access industry-leading manufacturing technology has played an important role in this. We now have application-specific chips for everything from artificial intelligence, to video rendering, to bitcoin mining.

AI chips typically provide a 10-1,000x improvement in efficiency and speed relative to CPUs, with GPUs and FGPAs on the lower end and ASICs higher. An AI chip 1,000x as efficient as a CPU for a given node provides an improvement equivalent to 26 years of [Moore’s Law-driven] CPU improvements.

-CSET, April 2020

Without going too deep into technical factors, there are many reasons to believe that this trend will continue, driving industry revenues for years to come (or at the very least, driving the next cycle). For example, chips with reusable IP can be separated into optimized subsets that then integrate into a complete package (in the industry this is referred to as chiplets).

This would dramatically reduce the cost of custom solutions, as will the utilization of AI in chip design. This can only be achieved with a common instruction set architecture, such as ARM or RISC-V (a competitor to ARM and X86, largely backed by China).

Another example is innovation in memory design. Some designs, such as Graphcore’s proprietary architecture, divide processor cores and memory such that each processor core has its own collocated bank of memory. Samsung is working with Xilinx (now owned my AMD) to develop customizable and programmable memory, that can be adapted to speed up data-intensive applications (such as AI).

SAMSUNG > TSMC?

Samsung is uniquely positioned. Samsung manufactures chips on behalf of customers (like TSMC). Samsung also designs its own devices, complete with its own software ecosystem (like Apple). Samsung is vertically integrated (like Intel), while at the same time, a semiconductor manufacturing platform for others to use (again, like TSMC). Samsung previously developed the SoC’s for the iPhone, before releasing its own smartphones.

Apple and Nvidia have both demonstrated that tighter hardware/software integration is the future. Because Samsung already has both a product ecosystem and a leading semiconductor fab, it is likely to also follow down this path. Samsung has a long history of copying Apple’s strategy (for lack of a more palatable description).

To articulate the crux of this investment thesis, the key insight is that “ecosystem economics” are driving the secular changes in the semiconductor industry. The key prediction is that Samsung will choose to leverage its vast product portfolio and semiconductor manufacturing leadership, to develop highly differentiated and superior products—the same way that Apple has done—enabling the company to expand and sustain higher margins and growth rates, that are in excess of what is expected in the street/base-case.

In addition, Samsung has robust financials, with $76B in net cash, a cost of debt that is a mere 100 basis points above the US 10-Year, and $36B in operational cash flow. (Note: These numbers may be slightly dated, but I want to be consistent with what is in the model attached to this article.)

VALUATION

It may be tempting to break Samsung down into individual segments and value the business as a sum-of-the-parts. This would be incredibly difficult to do without extensive access to Samsung management, given the complexity and scale of the business.

It may also be unnecessary. The investment thesis and valuation analysis rely on the simplifying assumption that Samsung is first and foremost a semiconductor business (~50% of operating profit), and that its extended product portfolio (smartphones, TVs, consumer electronics, smart devices) is essentially downstream of this, and that in the future these business segments will become increasingly integrated on both a hardware and software basis (and furthermore, that the software and hardware itself will become increasingly integrated). In fact, semiconductors are so fundamental to the global economy, that they are a leading indicator for the economy as a whole, and thus implicitly correlated with Samsung’s other, widely diverse, revenue lines (in theory).

The valuation model assumes a scenario where Samsung’s industry leadership enables it to maintain its 20-year average free cash flow growth rate (2.4%), beyond the initial forecasting schedule. In reality, this is conservative as it assumes that Samsung will not be able to leverage the pricing power of its newfound industry leadership or, in consumer electronics, follow Apple down the road of hardware/software integration. It is not hard to envision a future where Apple and Samsung are essentially competing product ecosystems, considering that Samsung already has 24% market share in smartphones (by unit volume). Compare this to Apple’s market share of 16%.

Based on these conservative assumptions, a discounted cash flow analysis yields a value of $97/share, compared to a current price of $46/share. Though a stronger scenario is more speculative, I suspect that Samsung will beat the expectations of the model and move towards the higher industry averages.

Samsung leads an industry with insurmountable barriers to entry, a manufacturing platform with tangible network effects, a business that is diverse both in terms of products and geographics, a proprietary product ecosystem that encourages customer loyalty (with network effects of its own), $117B in cash and short-term investments, and has grown revenue a 9.6%/year for two decades—with significant catalysts for margin expansion.

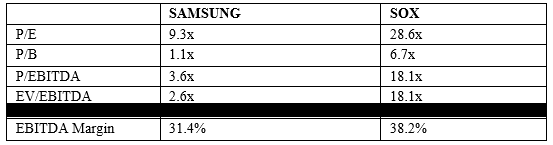

Note: This data is slightly dated, current as of late Q3 2022 (Author’s Work)

No matter how we define value in the modern context, it is hard to argue Samsung isn’t undervalued. For all the hype surrounding Nvidia, the 3000 series Nvidia chips came from Samsung. I had one myself, and loved it. The latest iPhones have Samsung displays.

RISKS

One of the most important aspects of this trade idea is that some of the execution risk is mitigated by the sheer size/scale of the business. This manifests itself in two ways. The first is that Samsung has a diverse product mix. It offers everything from household appliances to smartphones.

Second, the execution risk in the high-stakes semiconductor fab is inherently present across a basket of comparable companies (i.e. the SOX). Given that Samsung is the manufacturing partner for so many companies in the ecosystem, Samsung’s execution risk is almost systemic relative to the comparable portfolio. “Almost systemic” because there is only one alternative, TSMC.

In fact, many companies in the comparable portfolio have additional risks that Samsung does not have. They not only depend on Samsung to successfully execute on its manufacturing operations and roadmap, but must successfully execute on their own designs and products.

Aside from execution risk, there is some level of risk that Samsung will be unable to fully realize its intrinsic value, because it will always trade at a conglomerate discount. I brush these risks aside, as Apple is a sensible comparable. Perhaps hypothetical higher margins will be enough to carry Samsung into multiple expansion. It could also be argued that Samsung does not trade at a conglomerate discount, that it merely trades inline with prices on the Korean Stock Exchange. If true, multiples need only rise to 2019 levels to achieve 100% upside.

Alternatively, much like TSMC was at one time, perhaps Samsung is just flying under the radar and it is only a matter of time before investors in foreign markets realize the scale, significance, and opportunity—as they did with TSMC.

Geopolitical risks seem somewhat muted. A catastrophic disruption in Taiwanese trade would leave Samsung as the only foundry in the world capable of making the most advanced chips. However, Buffett has taken a strong stance on China. (See Munger’s defense of the Chinese Communist Party here.)

CONCLUSION

The key insight is that Samsung and TSMC have built powerful collaborative ecosystems, and the result is a broad and secular shift that will have extensive ramifications, some unknown, and possibly geopolitical in nature. The key prediction is that Samsung will leverage its hardware leadership, developing proprietary hardware/software integration that will increase the competitiveness of its products. The critical assumption is that, therefore, we can reduce the complexity of Samsung and analyze it as an integrated semiconductor-driven business.

Given the power of this secular shift, and the resulting dynamics, perhaps the question is not if Samsung would make a good investment, but when should one invest in Samsung? Buffett has already made the decision that TSMC is at an attractive price. But, I have some thoughts of my own…

It is both tradition and sage advice to not try timing the market. For those who have a preference for doing so, the technical complexity and predictable supply chain structure provides some refuge. Tracking the results of downstream customers (such as Nvidia), upstream suppliers (ASML, Applied Materials), or strategic partners (Qualcomm) can give valuable insights.

The best measure may be the performance of the commoditized memory market, where Samsung is the largest vendor. Given that the market is largely a commodity, used in almost every electronic device, a future recovery in this market would be a signal that the current cyclical trends are cycling over. In theory, this is the key indicator to watch.

For the long-term investor eyeing the horizon, there are many reasons to believe that Samsung will exceed the forecasts provided. The duopoly of Samsung and TSMC should increase pricing power. If Samsung leverages its resources to build products with tighter hardware/software integration (following Apple’s strategy), this could lead to vastly superior products. At the conceptual level, there are many catalysts (3D-stacking, chiplets / heterogenous integration, AI-powered chip design, etc.) for the enormous performance gains of recent years to continue for the foreseeable future—driving overall demand.

Let me know what you think about the TSMC / Samsung debate in the comments…

Be the first to comment