Darren415

By Breakingviews

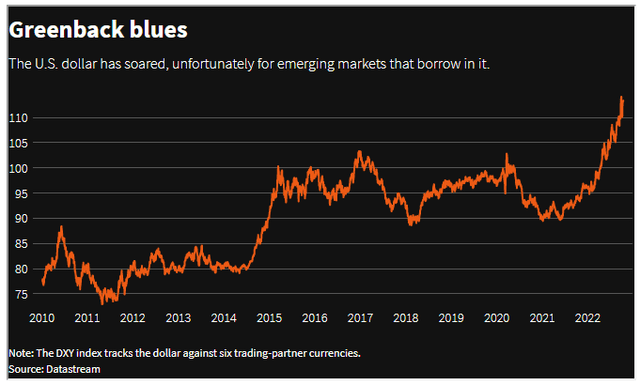

Everybody wants the dollar; everybody hates the dollar. The steroid-boosted greenback is the unwanted guest at this week’s annual meetings of the International Monetary Fund and World Bank in Washington, fueling complaints of capital outflows, sliding currencies and strangulated economic growth. The things that make the dollar such a fickle friend are also the reasons the world still needs it.

Two things have pushed the dollar to its highest level against other currencies in two decades. One is fear: War, disease and instability drive investors to the currency that’s deemed the safest and easiest to get in and out of.

The other is the sharp rise in interest rates engineered by the Federal Reserve to slow inflation, which was running at 8.2% in September. That makes dollar assets relatively more attractive and puts pressure on other central banks to raise rates too. A 2-year Treasury bond now offers a 4.5% yield, more than investors would have got on a 5-year Mexican government bond in early 2021.

The strong dollar kicks other countries in the shins, with varying degrees of pain. Nations whose exports don’t cover their imports must finance the difference – often in dollars.

Governments that run budget deficits must borrow to fund their spending. Some countries, such as Colombia, India and Turkey, will end 2022 worse off or no better on both measures than in 2013, when the Fed’s threat to tighten monetary policy caused a so-called taper tantrum, based on IMF estimates.

It’s true that the dollar and U.S. interest rates aren’t the only cause of discomfort in emerging markets. Spiking energy costs exacerbated by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and ongoing Covid-19 disruptions are damaging too.

But the strong greenback can turn such dramas into economic crises. Roughly two-thirds of emerging markets’ foreign borrowings are in dollars, according to the Financial Stability Board. The IMF reckons half of low-income countries are in debt distress, or close to it.

The Fed has no official reason to care about this. Its Congressional mandate is to pursue price stability and full employment in the United States. Minutes of the rate-setting committee’s September meeting released on Wednesday showed that, if anything, Fed chief Jay Powell and his colleagues were worried about not doing enough to squash inflation. Though some worried about hikes causing “significant adverse effects” on the economy, they meant the American one.

The Fed does pay attention to the effects of a global slowdown on the United States, and Vice Chair Lael Brainard this week acknowledged that sharp movements in exchange and interest rates could cause stress in financial markets. At the moment, however, these concerns remain secondary to the task of tackling inflation.

That makes it unlikely that the Fed will change course. As BlackRock boss Larry Fink put it in a speech in Washington on Wednesday, the central bank has one tool – a hammer – and all Powell can do is use it more frequently.

The urgency is greater because the Fed was late to start bashing inflation. Prices in Mexico, for example, started picking up at roughly the same time as in the United States. Yet the Bank of Mexico started raising rates in June 2021, nine months before the Fed.

Nor can the U.S. government do much to help, especially with the rising cost of living likely to be a key factor in midterm elections on Nov. 8. Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen has instead tried to push multilateral lenders like the World Bank and the IMF to woo private investors and make their own capital go further.

She also asked lenders to emerging markets to be more flexible in restructuring debt when things go wrong. That’s helpful, though is more like mopping up a spillage than preventing it.

For Americans, the strong dollar reflects relative economic strength. Bank of America chief Brian Moynihan pointed out at the International Institute of Finance conference on Wednesday that despite rising rates, the U.S. economy is in great shape. Customers’ bank balances are still “multiples” of what they were before Covid-19, and they’re spending around 10% more than they were a year ago.

All this will leave battered overseas dollar borrowers frustrated until the U.S. currency eases. In the long run, the experience of being at the mercy of the foreign-exchange wrecking ball will continue to drive appetite among emerging markets for an alternative go-to currency, but no such thing yet exists. The dollar still makes up 59% of the foreign currency reserve holdings reported to the IMF, albeit down from 70% two decades ago.

On the bright side, the problems with the dollar are also its best features. The currency has brought a stable medium for investment and trade that has powered developing markets to prosperity.

That’s partly because it’s guarded by a central bank not easily pushed around by politicians, and which pledges to get inflation under control regardless of who gets bruised in the process. Monetary policy is a selfish act, but while the Fed keeps conducting it independently, it’s better than the alternative.

Editor’s Note: The summary bullets for this article were chosen by Seeking Alpha editors

Be the first to comment