OlekStock/iStock via Getty Images

This article was written coproduced with Chris Volk.

Prior to writing on Seeking Alpha, I was a private real estate investor where I owned over $100 million in commercial real estate consisting of net lease properties, shopping centers, and warehouses. In addition, I also served as an investment banker where I brokered over $1 Billion off income-producing transactions.

Although owning private real estate was extremely lucrative for me, I took on enhanced risks such as leverage (personal guarantees), partnerships (tax complexity), and management (lack of transparency).

In fact, it’s because of these risks that I am now writing on Seeking Alpha, and helping readers understand the “lessons learned” and the benefits for owning shares in publicly traded Real Estate Investment Trusts (REITs).

I asked my fellow contributor at iREIT on Alpha, Chris Volk, to assist me with this article. Like our other analysts at iREIT, Chris has considerable experience – between 1994 and 2021 he introduced three successful net lease REITs to the public markets, two of which he co-founded.

He is also the author of “The Value Equation: A Guide to Business Wealth Creation for Entrepreneurs, Leaders and Investors,” which addresses the important contributions of business models to investor wealth creation.

After you read this article, you will understand why Chris is the “perfect” writer for this topic (private vs public REITs) as he did as exceptional job writing it and deserves 100% of the credit.

So, ladies and gentlemen, I present you with this masterclass on Private vs. Public REITs…

I have worked in real estate operating companies since 1986. That was when I moved from Atlanta, Georgia to Phoenix, Arizona to work with Mort Fleischer, a banking customer of mine who co-founded Franchise Finance Corporation of America (“FFCA”) six years earlier.

FFCA raised capital from private accredited investors through non-traded limited partnerships that were sold through various prominent New York-based investment banking firms.

Companies like FFCA used to be called “real estate syndicators.”

Today, this approach to raising capital would be done through non-traded REITs, with companies engaged in this activity simply called “asset managers.”

Non-traded Partnership/REIT vehicles have always been “sold,” not bought. There has always been a major inducement: A generous broker dealer fee, which tended to exceed the hefty fees paid out in corporate public initial public offerings.

Early players in this industry, like FFCA, offered no partnership liquidity at all, which gave rise to an informal secondary market. Often, our private limited partnerships would be trading at discounts to their original cost. Yet we would still raise new money in new illiquid partnerships. Investors were generally not steered to our earlier, discounted offerings.

Historically private partnerships and private REITs raised defined investor contributions and then were closed for further investment. They were “closed-end” funds. The state of the art today is the open-ended fund, which can continue to grow in size.

Given that such funds also offer some investor liquidity in the form of share repurchase programs, there is less need for informal secondary markets for existing shares. The share repurchase programs are also designed to promote a degree of investor liquidity at reported equity net asset values (“NAV”), rather than at discounts through third-party secondary markets.

Despite the comparative high fee structures our early investors incurred, the FFCA offerings generally performed well. We had no debt against the real estate and the real estate cap rates that we charged our restaurant and interstate travel plaza customers (our two principal areas of focus) were high, often exceeding 12%.

By the end of the 1980’s, our sources of funding were drying up and we looked to do what any number of other successful asset managers had done: We started to court large pension funds and to create increasingly efficient investment structures.

Raising capital from pension funds was painstakingly slow, and so I ultimately suggested in 1991 that we “roll up” our eleven fast food restaurant partnerships and list them on the New York Stock Exchange as a publicly traded REIT. If pension funds were interested in what we had to offer, they could invest in us through the public markets.

At the time, the REIT sector was embryonic, but a new generation of REITs was coming to market, led by the successful 1991 IPO of Kimco Realty (KIM).

The process of rolling up eleven partnerships with more than 100,000 investors took over two years, and FFCA finally became a publicly listed company in August 1994.

With an equity capitalization approximating $1 billion, we were among the ten largest REITs in the U.S. And, with their newfound liquidity, many of our investors sold out the very first day of trading, momentarily catapulting FFCA to the rank of the highest volume NYSE stock for the day.

Three months later, we would be joined by another successful partnership roll-up completed by Realty Income Corporation (O), which was then about a third our size. Today, Realty Income is the nation’s largest net lease REIT, and a dividend aristocrat included in the S&P 500.

Volatility: The Main Attraction

Private partnerships and private REITs have historically offered a win-win proposition. The selling broker dealers derive a win from a generous fee structure. Investors derive a win from a perceived lack of investment volatility.

Since privately traded REITs are valued based on real estate appraisal data, they tend to show little in the way of valuation volatility. There is a benefit to asset managers here: investors are generally happy to exchange investment returns for greater certainty and less return volatility.

In contrast to this, when I harnessed institutional capital in 2003 and 2011 to co-found two net lease REITs, the cost to raise the capital was far more efficient than our early partnership days, but the investors came in seeking higher rates of return. They also tended to be patient and less concerned with valuation volatility.

Over the years, I concluded that private REIT investors would often be happy simply getting their money back with a 6% low valuation volatility compound rate of return. When raising institutional capital, our investor return targets tended to be in the range of the mid-teens on up.

The founding institutional investments flowed into STORE Capital (STOR) in 2011 and concluded prior to our 2014 IPO. By the time of their exit in the first quarter of 2016, our founding institutional shareholders had generated returns that exceeded their initial expectations and mine; they made an approximate 26% annual rate of return.

Nareit |

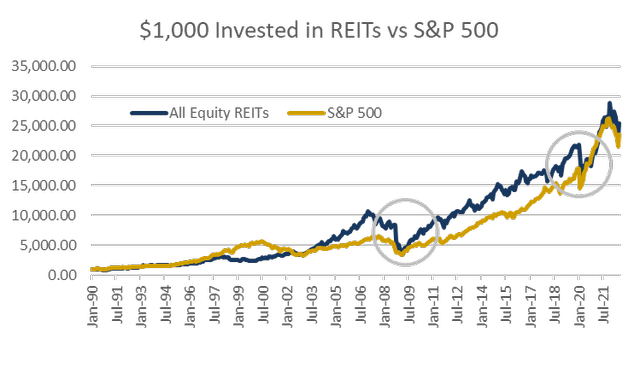

What follows is a chart of $1,000 invested in the FTSE All Equity REIT Index versus the S&P 500 since 1990. Ironically, though REITs have had historic dividend yields of roughly twice that of the S&P 500, they have been subject to greater valuation volatility.

In October 2008, at the beginning of the Great Recession, REIT total returns fell over 30% for the month, dropping another 23% the following month.

By contrast, the performance of the S&P 500 for the two months were losses of 20.2% and 8.6% respectively. During the pandemic, REITs sold off 7% and 18.7% In February and March 2020. Meanwhile, the S&P 500’s move in February was a loss of nearly 19%, with a 4.3% recovery the following month. You can see these areas of heightened REIT volatility in the circled chart areas.

A False Choice

My personal view is that swapping volatility for lower and more certain return is a false choice. Warren Buffett has often noted that he does not buy stocks. Rather, he invests in companies.

Having such a mindset means that he is less concerned with valuation volatility providing the underlying business models and fundamentals of the companies in which he invests remain sound.

Likewise, having had the privilege to work with institutional investors as we started two companies, I noted their patience. They focused on underlying fundamentals and then looked for opportune moments to harvest their profits. Volatility did not especially bother them.

Investors in private REITs are the ultimate “buy and hold” shareholders, agreeing to own a comparatively illiquid investment and often even reinvesting their dividends.

Only, unlike Warren Buffett, they have less control over the timing of any exit. They have ceded control to asset managers having a potential financial incentive to maintain the status quo.

But, as the chart shows, had you been a buy and hold REIT investor between 1990 and 2022, you could have likely been happy socking away your 10.5% annual rates of return.

In periods of volatility, overall REIT business models tended to hold up, with comparatively few companies cutting or suspending dividends.

The very notion that volatility ceases to exist simply because an investment is not traded in a liquid marketplace is somewhat silly.

It’s like the age-old question of whether a tree that falls in a forest with no one seeing it makes a sound. At FFCA, we reported shareholder returns for years based on appraised NAV’s.

Then, in one massive transaction, we listed the shares on the New York Stock Exchange and their values became evident to all. At the time, we made a conscious bet that public market values, over the long term, would be the same or better than the values in private, less liquid, less diverse hands.

A Case Study: BREIT

In 2017, Blackstone (BX) introduced the Blackstone Real Estate Income Trust, an open-ended private REIT designed to deliver private real estate asset management to retail investors.

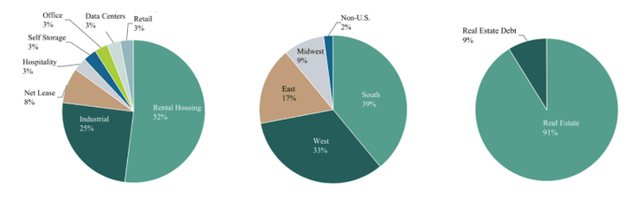

The idea was to own a highly diverse group of institutional real estate assets. As of June 30, 2022, the portfolio appeared like this:

As of June 30, 2022, BREIT reported that it:

“owned a diversified portfolio of 4,917 properties and 26,203 single family rental homes concentrated in growth markets consisting of income producing assets primarily focused in Rental Housing, Industrial, and Net Lease properties, and to a lesser extent Data Centers, Self-Storage, Hospitality, Retail, and Office properties.”

BREIT is a juggernaut.

Nareit, Morgan Stanley, BREIT |

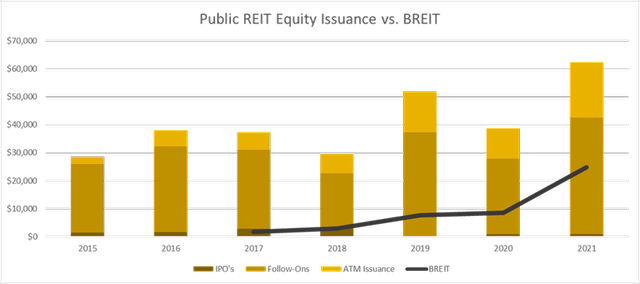

During 2021, the private REIT reportedly raised about 70% of all the equity capital raised by private REIT companies. Since its 2017 inception, the company has raised a staggering $59.9 billion, repurchasing approximately $7.3 billion of this amount through its stockholder liquidity program.

As of June 30, the net asset value of the equity was reported to be $68.3 billion. To add some perspective, if BREIT were a public company, its reported value would have the company ranked fifth amongst all equity REITs in terms of equity market capitalization.

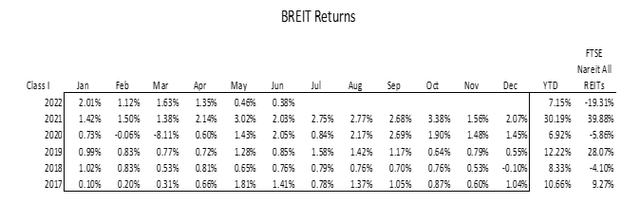

In terms of performance, BREIT has outperformed the MSCI broader REIT index, with monthly and annual rates of return is shown below. Note the comparative lack of volatility, with the exception of the 8% negative return at the onset of the pandemic in March 2020. The reported returns are for Class I investors where the investment are not subject to broker dealer fees.

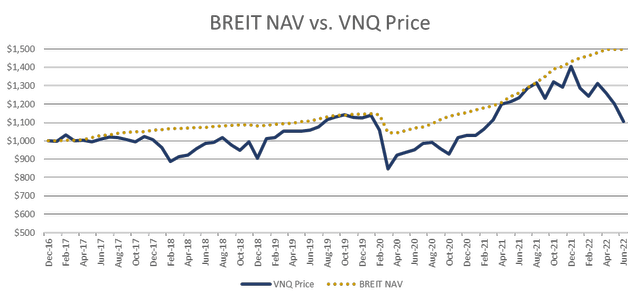

The level of outperformance owes much to BREIT’s changes in reported value. When plotted against the reported value of the Vanguard Real Estate Index Fund ETF (VNQ), the comparison since the end of 2016 is as illustrated below.

At the end of June 2022, BREIT’s NAV per share had risen roughly 50%, versus just a 10% rise in VNQ’s per share valuation. Much of the performance divergence rests in BREIT’s investment mix. Approximately 80% of its investments are centered in industrial and residential single family rental properties.

Private REIT Business Model Challenges

I am a big believer in the power of solid business models to drive investor returns. That notion is the centerpiece of my recent book: “The Value Equation: A Business Guide to Wealth Creation for Entrepreneurs, Leaders and Investors,” recently published by Wiley. When comparing privately traded REITs to their public counterparts, a number of business model differences stand out:

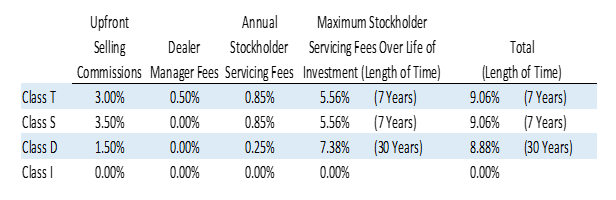

1. Investment Fee Loads: Private REITs tend to pay higher fees to their underwriters than their public counterparts, which means that less is typically invested in real estate or available for shareholder distribution. The current version of private REITs is more efficient than the days where less than 90% of each dollar raised was actually invested in real estate, but there is still materially higher frictional cost.

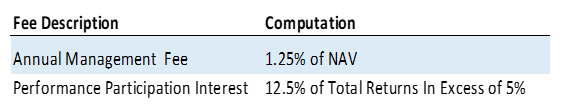

BREIT

In the case of BREIT, the fundraising fees are high. On an investment of $10,000, an investor can expect to part with about $900 in selling commissions and fees paid to dealer managers and brokers, of which a third is paid up front and the rest over time in the form of “Annual Stockholder Servicing Fees.”

For Class T and S investors, the fees amount to about .85% annually. The fee drops to .25% for Class D Investors, though it is paid out over a longer period of time.

BREIT

Private REITs tend to pay the same fundraising-related fees for all dollars raised. Public REITs, by contrast, can have IPO costs in the area of 5%, with subsequent equity issuance costs falling off markedly thereafter. “At the Market,” or ATM deals are widely available to seasoned public companies, involve shares issued discretely over trading desks and generally incur costs below 2% of the proceeds raised.

2. Mandatory Distribution. Private REITs are characterized by their known investor distribution levels. An investor who purchases private REIT can expect to receive immediate cash distributions, even though the money they just put up has not likely been invested.

This often means that investors are receiving early distributions derived from their own funds. Put another way, the fee load to create a private REIT can rise further relative to a public company because money is often raised up front and not in arrears.

So, whereas public companies tend to select real estate they want to invest in and then later turn to the equity markets to right size their balance sheets, private REITs are positioned to do the opposite. The amount of capital they raise defines the amount of real estate they have to purchase. The fact that they are paying out distributions on uninvested cash can elevate the investment urgency.

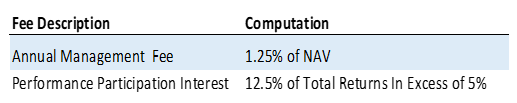

3. Management Fees: Like their public counterparts, private REITs incur direct operating and property management costs. Because they are externally advised, the costs of much middle and executive management are not borne by the REIT. However, the management fee costs can often rise to levels far higher than those that might be incurred by a public self-managed REIT.

BREIT

In the case of BREIT, the management fees are significant.

The annual management fee is computed as a percentage of the determined equity value (“NAV”), while the performance management fee is computed as a percentage of the total equity return.

For the first five years of BREIT, the performance management fees averaged more than 150% of the base asset management fee, meaning that the average total fee approximated 3.25% of equity NAV.

I have always tended to look at costs as a percentage of total assets. Given a company having leverage of roughly 50% of total assets, the collective fees amount to a little over 1.6% of total assets annually.

To put this into some perspective, this amount approaches three times the total cash costs to run a public net lease company like STORE Capital, where I served as the founding CEO.

Given STORE’s emphasis on direct originations, a number of net lease companies actually had leaner operating costs. The operating cost discrepancy gets larger when adding in BREIT’s direct property operating and general administrative costs.

4. Liquidity. Public REITs trade daily, offering substantial investor liquidity. At the end of June, 2022, average daily REIT trading volume approximated $7.4 billion against a collective equity value of the FTSE NAREIT All REITs equity index of $1.5 trillion. That equates to nearly 15% a month and well over 100% of equity value annually.

Private REITs are implicitly designed for “buy and hold” investors, with valuations marked at appraised values. Presuming that investors hold their investment for a minimum period (often a year), they can sell out for no discount to the set value per unit.

However, private REITs are not designed to experience the kind of trading that happens within a public company. As a result, the offering terms tend to leave investor liquidity decisions to the managers. Should real estate markets be inhospitable, or should there be excess investor liquidity demand, managers typically have the ability to limit or curtail investor liquidity.

In the case of BREIT, there is a share repurchase plan which is capped at 2% of the shares per month and 5% of the shares per quarter.

With no liquid market for the company’s securities, BREIT and other private REITs offering such liquidity options require the maintenance of excess liquidity in the form of cash, borrowing capacity or investments in liquid debt holdings.

All of these can potentially serve as a potential drags on investor returns when compared with their public counterparts, which don’t require such liquidity backup. Absent this, the only way to realize liquidity would be to liquidate real estate holdings, which can potentially pose execution risk.

5. Dividends. Many public REITs offer their shareholders with material dividend protection, which comes in the form of a low dividend payout ratio relative to the free cash flow available to pay such dividends. Private REITs, on the other hand, tend to pay to investors substantially all the cash flows that are available to distribute.

From a business model standpoint, low dividend payout ratios not only serve to protect investors from downturns, but the reinvestment of retained cash typically contributes meaningfully to AFFO growth.

6. Borrowings: Publicly-traded REITs, especially larger ones, commonly bear corporate credit ratings of BBB-/Baa3 or better, meaning that they have ready access to unsecured investment-grade borrowings. This also implies conservative levels of leverage. Private REITs tend to use higher levels of borrowing than their public counterparts, while often relying most on secured borrowings.

From a business model perspective, the lack of investment-grade ratings typically allows non-traded REITs to employ higher degrees of leverage, which is important when it comes to delivering investor returns.

7. Tax Deferrals: Because private REITs tend to have high dividend payout ratios, coupled with higher borrowings, their distributions can often exceed reported taxable income per share, which means that some of the distributions will not be immediately taxable (some of the taxes are deferred). This business model difference can be advantageous to taxable investors.

The differences between public and private REITs go beyond the seven business model differences to include three investment characteristic contrasts:

1. Private REITs Tend to Be Externally Advised. I have helped take public and lead three publicly traded REITs, all of which were self-managed. For a REIT to go public, this is almost a necessity. Investors want management to be “shoulder to shoulder” with them. No investment banker I have ever spoken with has ever supported the idea of taking public an externally advised REIT. But private REITs tend to be just that.

2. Private REITs Often Lack Sector Specialization. Public REITs tend to be specialized, with leadership teams skilled at investing and managing real estate centered in a target property type and market. This means that sector investment diversity is the responsibility of the shareholder and achieved by investing in the shares of multiple companies or in REIT exchange traded funds (“ETFs”). Private non-traded REITs are often far less specialized, with real estate holdings spread over many sectors.

3. Private REITs Tend to Have More Conflicts of Interest. The appraised net asset valuations of private REITs are typically determined by the very management companies who realize fee streams often pegged to the asset values they assign.

Meanwhile, public REITs trade daily with, at best, a modest regard for underlying estimated net asset value. Investors in the public arena might be additionally captivated by dividend yields, price/earnings-to-growth (PEG) ratios, leadership teams, corporate business models or other investment characteristics.

Private REIT’s like BREIT can often include investments in real estate joint ventures completed in concert with other pools of capital managed by the manager.

Speaking as a three-time public company REIT leader, if I were to introduce an externally advised REIT having a 100% dividend payout ratio, together with modestly higher leverage, a reliance on secured unrated borrowings and a comparatively high expense structure, I would expect my company to trade poorly.

Possible shareholder liquidity constraints, investment pressures arising from investing in arrears and a lack of sector or regional specialization could also be expected to be harmful to my valuation.

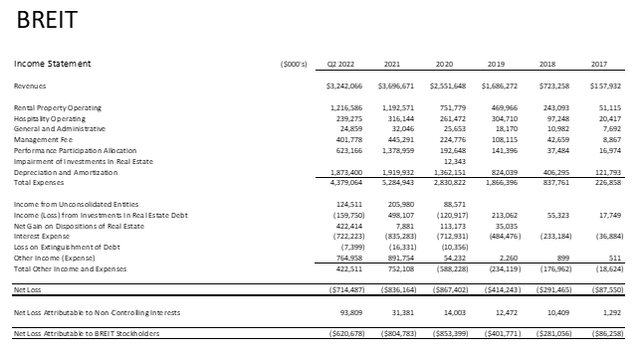

BREIT’s Financials

Having raised a net $52 billion in equity over five and a half years, BREIT’s growth has been nothing short of incredible. For the first half of 2022, annualized revenue grew at a rate of more than 75%.

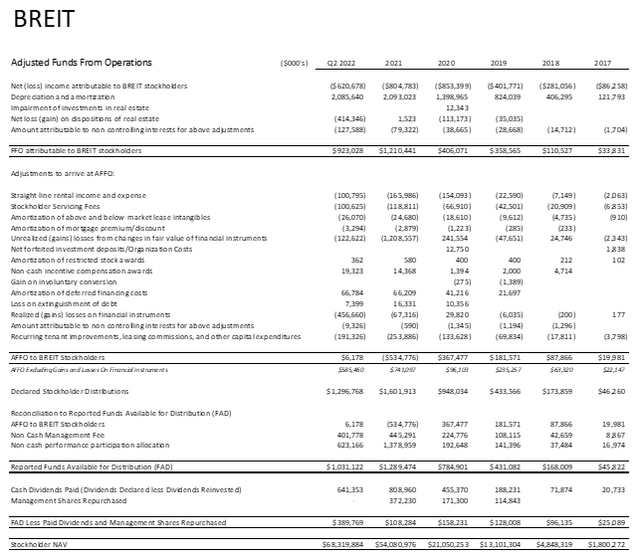

The following shows the trend of BREIT’s Adjusted Funds from Operations (“AFFO”). To do this, I used my own understanding of AFFO, which includes real estate maintenance capital expenditures. The company’s disclosure here is different, excluding maintenance capital expenditure from AFFO, but including them as an adjustment to Funds Available for Distribution (“FAD”).

Importantly, Blackstone has elected to not take its management fees from BREIT, instead reinvesting them into series I shares, though BREIT has redeemed some of the shares.

As a result, BREIT’s reporting backs the management fees out of AFFO. I elected not to do this because BREIT’s election to take its fees in shares is completely voluntary and at the discretion of the manager. Likewise, the manager can later sell the shares back to the company. Finally, approximately half of BREIT’s investors elect to reinvest their shares, which limits the amount of cash that must be distributed.

Using a traditional means of AFFO computation, BREIT would historically have a dividend payout ratio exceeding 100%. However, when adding back the management fees the reported FAD is more than sufficient to pay distributions to stockholders who elect to receive them, together with reported manager share repurchases.

That said, the reported FAD would fall short of dividend requirements if all shareholders elected to have their dividends paid in cash. Finally, I show the shareholder reported NAV at the bottom. You can perhaps estimate the effective AFFO multiple, which will appear high relative to the public REIT counterparts.

One of my observations from the preceding analysis is that BREIT is growing so fast that it is hard to determine the company’s business model. This is a result of breakneck pace at which BREIT has raised capital and the fact that the investments funded with the capital are made in arrears.

Will the company be able to generate AFFO that can support both the full cash payment of management fees and the full distribution of dividends?

Time will tell.

The Business Model Will Out

When I directed the 1994 public listing of FFCA, a major motivation was the thought that public companies were bound to have higher valuations than private companies. This idea stemmed from public company portfolio diversity, investment liquidity and the fact that the best companies tended to be self-managed.

With self-managed companies, shareholders not only owned the real estate, but they owned the underlying management company. Over the years of leading public companies, my expectations have generally been met, with our share values typically exceeding underlying NAV.

A big part of my thought regarding the potential of our public companies to outperform our prior private partnerships stemmed from simple business model realities. We were able to run public REITs for a fraction of the cost of what would be incurred with private vehicles.

Private REITs have comparative unavoidable cost drags resulting from higher broker-dealer fees, higher management fees and the frictional drag of investing in arrears while paying dividends on uninvested shareholder equity. With today’s open-ended private REIT model, there is the added friction of maintaining liquidity for occasional investors who might wish to sell back their shares.

Lowering costs to generate Alpha was at the heart of John Bogle’s thoughts when he started Vanguard and created the first index fund. His groundwork paved the way for the proliferation of exchange-traded funds ((ETFs)), which allow investors to own diverse baskets of stocks having the potential to general relative alpha due to the lack of costly management fees.

Private REITs, with their high fees and comparative business model shortcomings, stand in contrast to John Bogle’s conviction that efficiency matters when it comes to investor return delivery.

With respect to long-term investment performance, I believe that there is little that beats owning shares in real estate companies having strong, proven business models which support the consistent payment of shareholder dividends.

If you are a “buy and Hold” investor, you are buying the company and not the stock. And when volatility strikes, as it always does, you simply think of that unseen tree in the forest and whether it makes any noise as it falls.

Then, over time, as Shakespeare wrote in The Merchant of Venice the “truth will out”. Only here, it’s the “business model will out.”

Be the first to comment