sankai

Macroeconomic Outlook: Macro Road Map Is Complicated and Fragmented

By Francis A. Scotland

It is a complicated and fragmented world, all adding to heightened uncertainty about next year’s outlook:

- U.S. monetary authorities have moved aggressively since March to put out the inflationary fire that they started with extreme but opposite measures last year.

- China’s policymakers are adding stimulus to their economy to ensure that all the depressing measures they inflicted in the past year do not turn into deflation.

- European policymakers are caught betwixt and between—fighting the worst inflation in decades while subsidizing households from the soaring energy costs responsible for that inflation.

- U.S. housing is in a recession, caused by high rates. However, the auto sector is rebounding, and car prices are flattening out as normalizing supply factors lift production, inventories, and sales from depressed levels.

- The Treasury yield curve signals rates are high enough to bring inflation back on track. On the other hand, the broad stock market is still not priced for a U.S. recession despite near universal expectations of one from both public and private sector forecasters.

Amid the crosscurrents, two themes have prevailed during the post-pandemic years, which lend some perspective to the macroeconomic roadmap ahead: namely, the bipolar swings in macro policy and the forces of economic normalization. The lockdowns knocked the world severely off the prevailing path of “normal.” Since then, judgment—most of it bad—about what was needed to get back on that path has led to some wild swings in macro policy. The effect of each extreme policy pivot plus the natural tendency to normalize has flowed through into asset markets, real economic activity, and inflation. In 2023, we expect it should be no different.

Global public health-mandated lockdowns in 2020 triggered the biggest collapse in gross domestic product (GDP) since the Great Depression and enormous supply-side distortions. Normalization started literally weeks and a few months after the lockdowns, economic activity rebounding rapidly. But U.S. economic policy, in particular, turbo-charged the recovery with the most extreme combination of macroeconomic stimulus measures taken in peace-time history. Excessive spending and the flood of liquidity overflowed into commodities, asset markets, and real estate prices, leading to booming economic and job growth, and ultimately soaring price inflation. Dismissive of its scale, the Federal Reserve (Fed) viewed the inflationary elements of this rebound as transitory, a perspective which only drove inflation higher.

We are now watching this movie play backwards. The Fed capitulated this year from life of the party to party pooper, changed its inflation story from transitory to structural, and turned liquidity from a flood to a drought. Inflation turned to deflation in crypto markets, commodities, stocks, bonds, and most recently, real estate prices. The scale and speed of the reversal in policy is unprecedented, and the failure of judgment at the Fed, both disappointing and disturbing, really muddles the outlook. How restrictive policy has become is debatable, even at the Fed. St. Louis Fed President James Bullard dusted off the Taylor rule—a policy rate-targeting equation linking short-term rates, inflation, and economic growth—to suggest that a terminal rate higher than market expectations of 5 to 7% is possible. The San Francisco Fed published research that suggests we could be there already. They estimate that the “effective” Fed funds rate is already approaching 7%, after adjusting for financial conditions.

What is next for 2023? Will the U.S. experience the recession nearly everyone seems to see coming?

The yield curve says policy is restrictive enough with rates where they are. This signal plus the reversal of last year’s inflationary movie sequence and more supply-side normalization should lead to significantly slower inflation and a softer labor market. The most intense period of economic softness is likely to be in the first half of 2023, based on the weight of leading indicators. However, there are a range of factors that could limit downside recessionary forces, including: the recent plunge in energy prices, the rebound in the U.S. auto sector, and what could turn out to be a rapid decline in inflation. The conditions for a credit crunch, commonly seen ahead of other U.S. recessions, do not exist currently. There has been no extreme period of lending; balance sheets in households and corporations are in relatively good shape. What is not known is the state of the private credit and equity markets. Recession odds increase significantly if Fed Chair Powell remains dogmatic on the need to create labor market slack. However, he has proven himself impressionable when it comes to the data. A pause in rate hikes seems very probable, especially if the data show a steep and deep decline in inflation.

Outside of the U.S., the global economy is already in recession due to the effects of the strong U.S. dollar and a very weak China. China has started to back away, slowly, from the policies that have been depressing activity. If the dollar corrects lower as the U.S. economy decelerates and inflation retreats, and the U.S. avoids a bust, the world economy could be stabilizing by this time next year.

Developed Markets Fixed Income: A Better Quadrant for Bonds

By Jack P. McIntyre, CFA

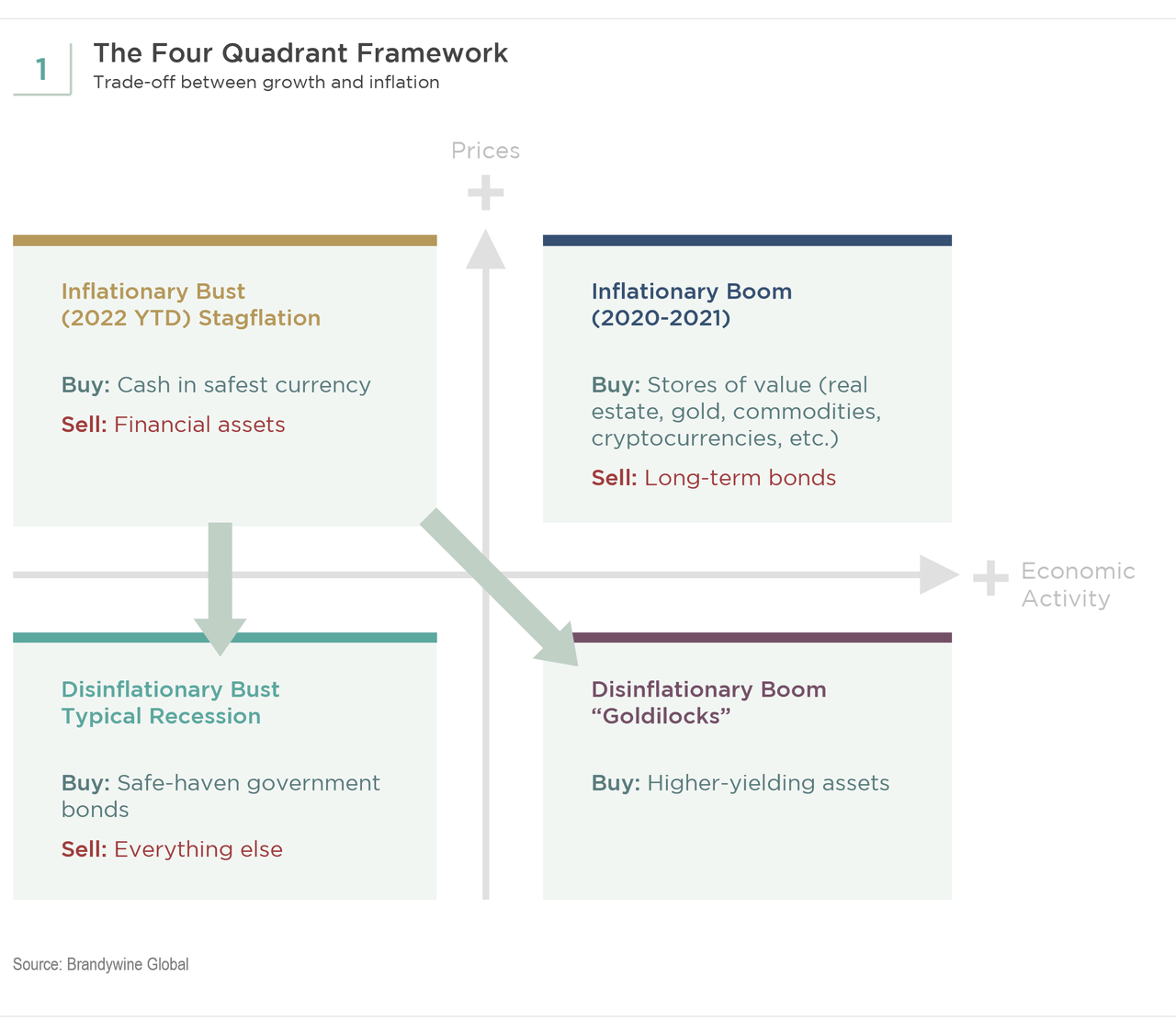

We are increasingly confident about the destination of bond markets in 2023, and that is toward a disinflationary environment. We are less certain about the path and timing of the journey. However, it will not be a repeat of 2022, a year of stagflation—or an inflationary bust—where the only asset class to do well was cash (see Figure 1). Instead, 2023 will provide a different outcome for bond markets.

First, the bond math now works in favor of the asset class, meaning that the coupon return will become a more influential source of the total return for bonds. That was missing in 2022 as most bonds had little income cushion to offset the sharp increase in yields.

Second, in addition to the favorable technical developments for bonds in 2023, two potential disinflationary outcomes for the global economy also support fixed income, particularly if an investor’s time horizon is the entire year. We expect a job-killing recession is necessary to break inflation and get it close to central banks’ 2% target. That means there will be meaningful weakness in the labor market globally. Under this type of disinflationary bust, a typical recession, higher-quality sovereign bonds are the best returners. Risk assets generally do not do well in this scenario. While a disinflationary environment coupled with moderate growth is also possible, i.e., a “Goldilocks” scenario, a recession is the higher probability outlook, at least for the first half of the year.

Why are we positive on bonds? There is a perfect trifecta set to unfold around inflation, which should take inflation lower:

- In the developed market (DM) world, central banks are advocates of increasing tighter financial conditions. There is a long list of developments creating these tight conditions, including high short rates, global real money supply that is sharply negative, a strong U.S. dollar, skyrocketing mortgage rates, and weak global growth and trade. This list is not all inclusive but reflects a policy rate in the U.S. that is already very restrictive.

- Tight financial conditions are only part of the story. The other part is that the U.S. and global economies are slowing or already in recessions at a time when the lag effects of these tight financial conditions are beginning to impact their underlying economies. Globally, we know housing is already slowing yet mortgage rates are still very high. Inventory levels are still elevated, and profits are being squeezed, which will lead to weaker employment—and lower capital expenditures (capex). China’s economic growth has been stymied by its zero-COVID policy and an ongoing repricing of the property market. Without the current inflation, central banks would probably be thinking about easy monetary policy.

- There are signs that inflation has already peaked and could come down precipitously, including:

- Business prices for manufactured goods are falling sharply, based on ISM Manufacturing Prices Paid.

- Import prices in the U.S. are declining, evidenced in lead CPI data.

- The China Producer Price Index (PPI), which tends to lead headline inflation in the developed world, is receding.

- Supply disruptions are reversing rapidly.

- Container freight rates have plummeted.

- Housing prices/rents have peaked and are declining.

- Wages are showing some signs of peaking.

- Commodity prices are falling.

- Longer-term Inflation expectations are still anchored.

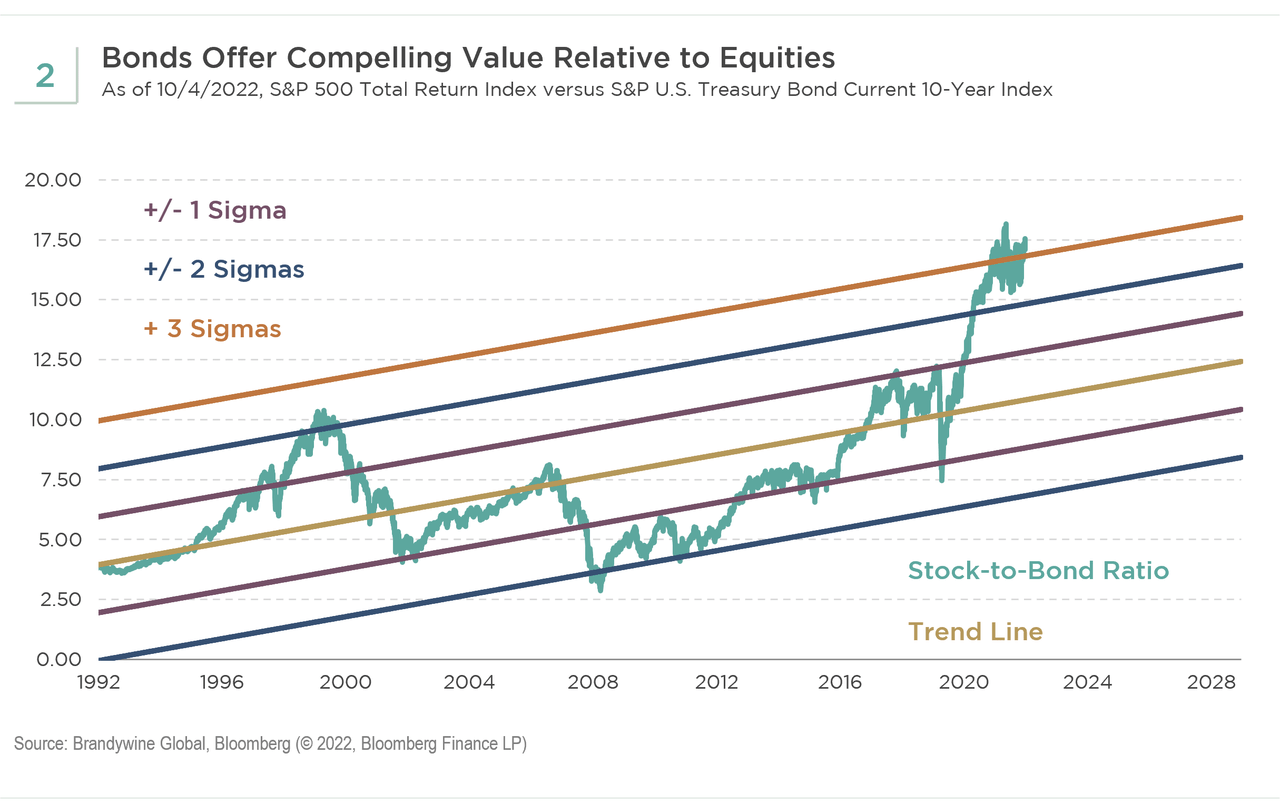

This perfect trifecta points toward bonds outperforming equities in 2023. And we know that coming into 2023, bonds offer more compelling value relative to equities (see Figure 2).

Developed Market Bond Road Map for 2023

Our overall theme for next year is bullish but with pauses until each of the following conditions is satisfied.

- Yield curve inversion. We have met this condition, which suggests a growing risk of recession. Even the 3-Month T-bill/30-Year Treasury curve, one of the most conservative relationships to use as a gauge, is inverted.

- Positive real policy rates. We need to see real, inflation-adjusted policy rates in developed markets turn positive or at least return to zero. Policy rates must be above inflation to meet the adequate tightening requirement. If inflation does not move meaningfully lower in early 2023, the Fed funds rate may have to hold in the 5% range for much of the year. If Fed Chairman Powell is really going to be like former Chair Volcker, the Fed will keep rates higher for longer even if inflation comes down—and unemployment potentially increases. For decades, real policy rates were positive using core PCE. Do we need to return to that pattern? It was not until post-GFC that real policy rates became and stayed negative.

- Slowing economy/recession. We need a slower economy to break inflation, and there are signs that this condition is occurring. But what type of recession will we get, and will the Fed be okay with it? The risk to slower growth is extended stagflation, which would be negative for bonds and equities.

- Weak employment. There are no real signs of employment weakness yet. Will it take a meaningful deterioration in the labor market to break inflation? Most likely. While typically a lagging indicator, employment likely will demonstrate an extra lag this cycle because companies that struggled to find workers post-pandemic may be reluctant to let them go too quickly.

- Lower inflation. Time will eventually bring inflation to around 6% from 8%. However, we need to see a meaningful move lower in inflation to avoid a protracted period of stagflation.

Satisfying each step is necessary but alone not sufficient to ignite a new structural bull market in bonds and truly break inflation. Until we see all these conditions met, we may be more tactical in how we manage the sovereign bond portion of global bond portfolios. We favor having more duration exposure in Treasuries as there is more relative tightening of financial conditions in the U.S. than in European bonds or Japanese government bonds. There is an increasing risk the Bank of Japan (BOJ) backs away from or adjusts its yield curve control (YCC). Lastly, investors will know central banks are nearing the end of their tightening cycles when they shift away from their message of “the risk of doing too little outweighs the risk of doing too much.”

Global Currencies: Growth Prospects Point to Weaker Dollar

By Anujeet Sareen, CFA

After experiencing a historically strong year of appreciation, the U.S. dollar now appears overvalued against a broad basket of currencies, and macro fundamentals are poised to deteriorate in 2023. The primary drivers of the dollar in 2022 were relative growth outperformance and relative monetary tightening. Although U.S. real growth decelerated in 2022, the substantial growth shocks in Europe, driven by the Ukraine war and energy shock, and in China, resulting from its restrictive zero-COVID policy and property market crisis, led to relative U.S. economic outperformance. In parallel, the U.S. Fed raised interest rates by 400 basis points, more than nearly all other major central banks.

Looking forward, relative growth dynamics are not likely to favor the U.S. in 2023:

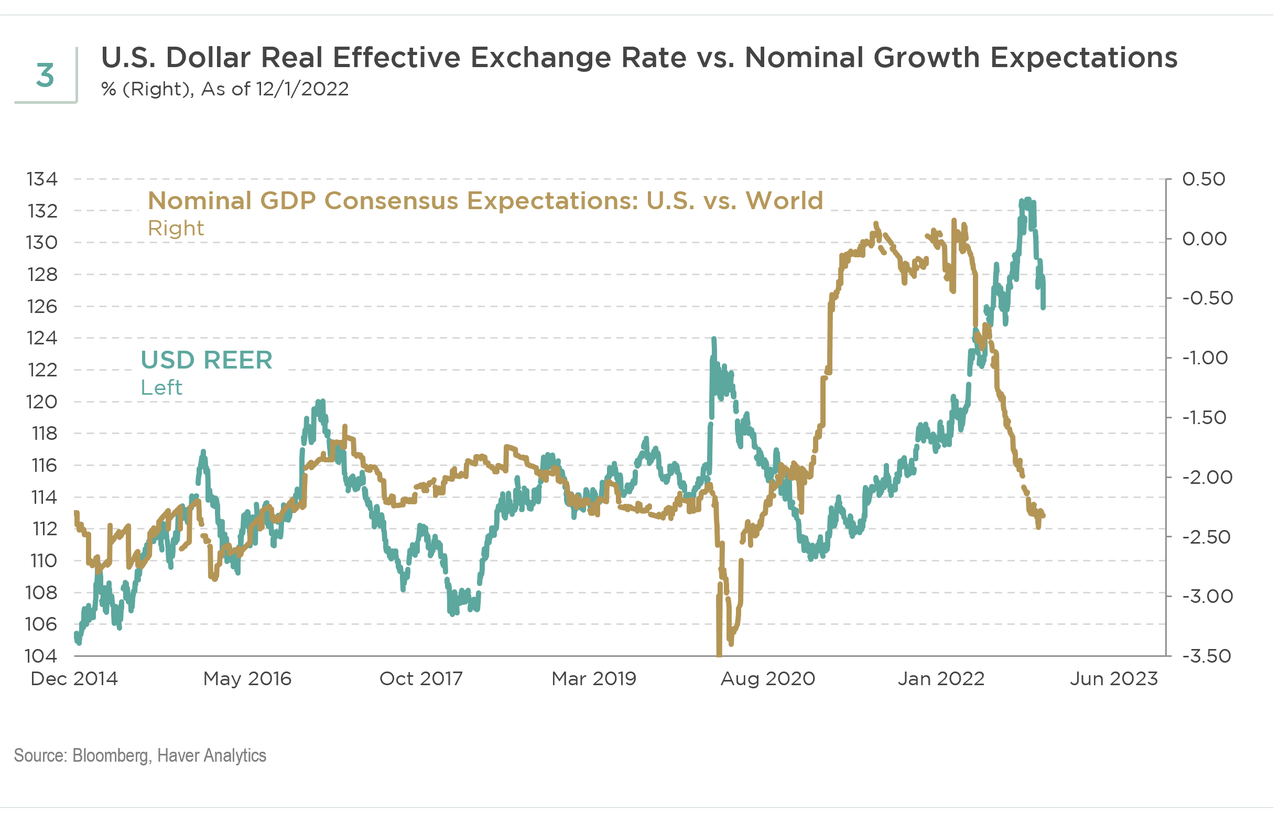

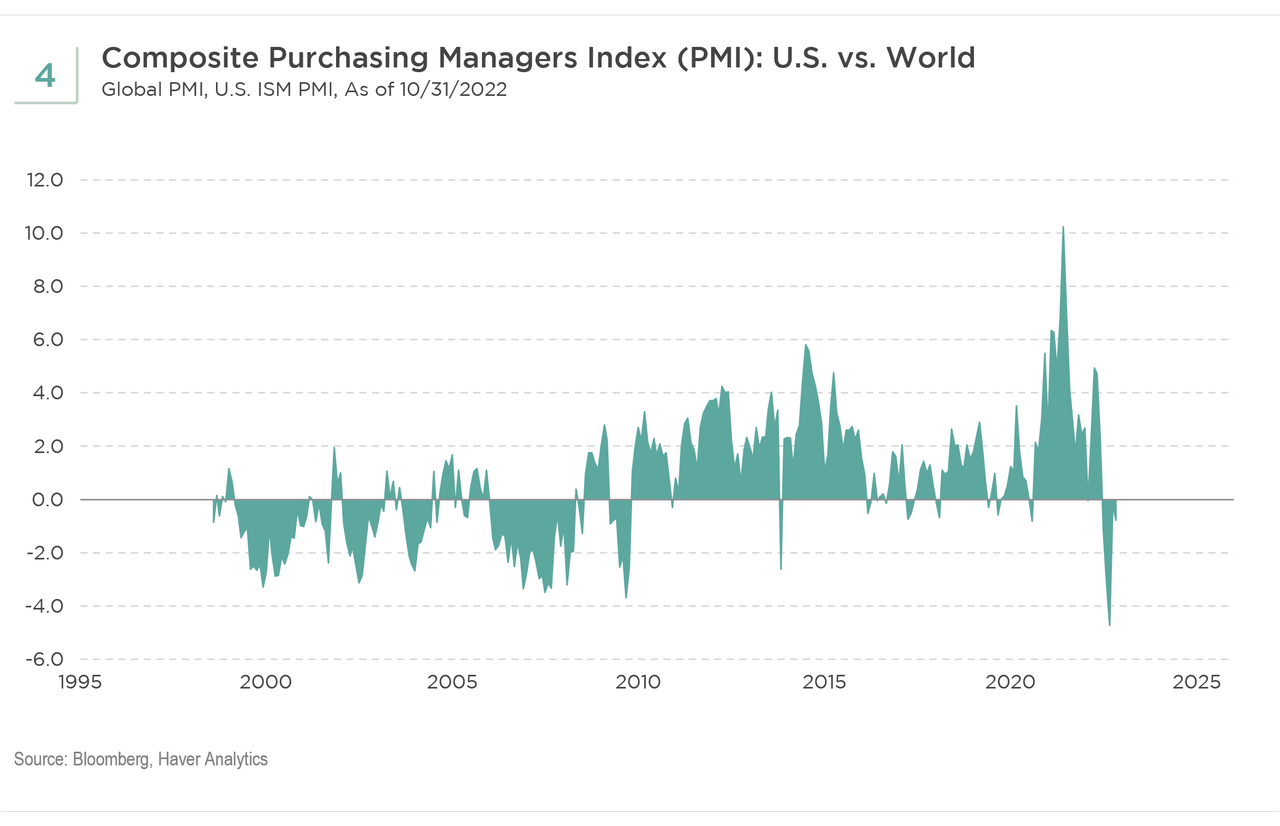

- One, the U.S. economy is confronting the lagged consequences of a more pronounced monetary tightening cycle than most major countries. The higher cost of interest and the higher level of the dollar will challenge 2023 U.S. growth (see Figure 3 and Figure 4).

- Two, the shocks that constrained Europe and China are likely to diminish, if not reverse altogether as the year progresses. Europe’s energy challenges are not yet resolved, but if Europe is able to manage through this winter with its elevated energy storage levels, then it buys valuable time to further develop longer-term solutions to its energy needs. At the same time, Russia’s inability to sustain its advance through Ukraine raises the probability that some détente unfolds in 2023 as well. Meanwhile, China’s policy toward COVID has finally started to shift to a more viable long-term strategy, allowing the populace to increase its natural and vaccinated resistance to the virus, which, in turn, should allow for a more significant recovery in the service sector, notably in tourism. In addition, with Xi having secured his leadership for the foreseeable future, Chinese policy concurrently may become more supportive of the property sector. Indeed, the very chaotic nature of shifting from the zero-COVID strategy involves additional policy support to smooth the economic transition. Hence, the prospects for Chinese growth over the coming year have improved.

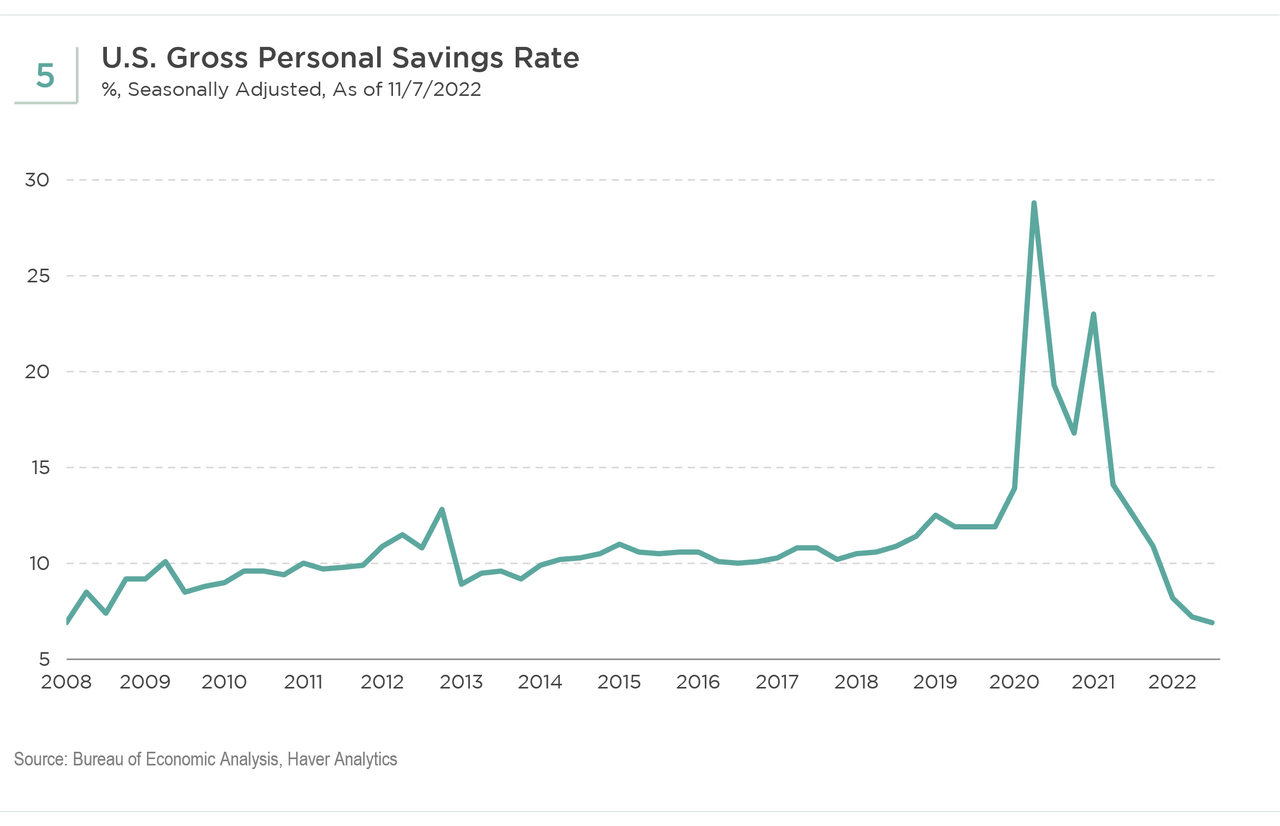

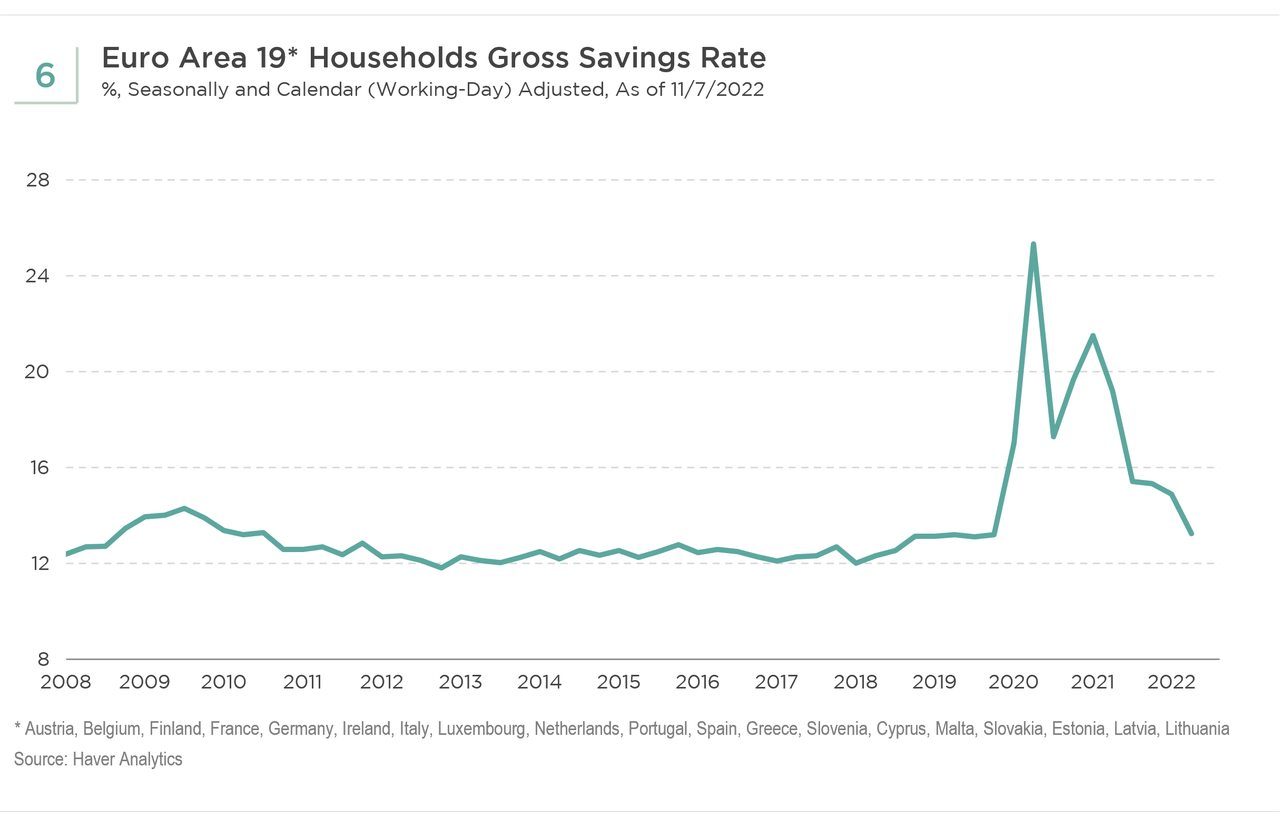

- Three, U.S. households have lowered their savings rates to well below pre-COVID levels, essentially running down the excess savings generated in 2020 and 2021. However, households outside the U.S. are only just starting to tap into their own excess savings. This dynamic, too, offers more support for consumption outside the U.S. than inside the U.S. (see Figure 5 and Figure 6).

- All in all, relative growth prospects between the U.S. and the rest of the world are likely to deteriorate, favoring a weaker dollar, all things equal.

Relative monetary policy is also likely to move in parallel with the shift in relative growth. The Fed is likely approaching peak policy rates near 5%, but the European Central Bank (ECB), given its policy tightening cycle began later, may still raise interest rates further in 2023. European inflation is likely to slow somewhat later, and fiscal policy is more supportive of growth in Europe than the U.S. This relative shift in monetary policy is constructive for the euro, all things equal.

In Japan, monetary policy also is poised to begin tightening in 2023. Governor Kuroda, one of the principal architects of Japan’s aggressive reflationary monetary policies, is set to step down in early April. While his successor has not yet been determined, the recent acceleration in Japanese inflation, in contrast with the deceleration in U.S. inflation, has increased the probability of a shift tighter in Japanese monetary policy, which would be constructive for the yen.

All things, however, are not quite equal:

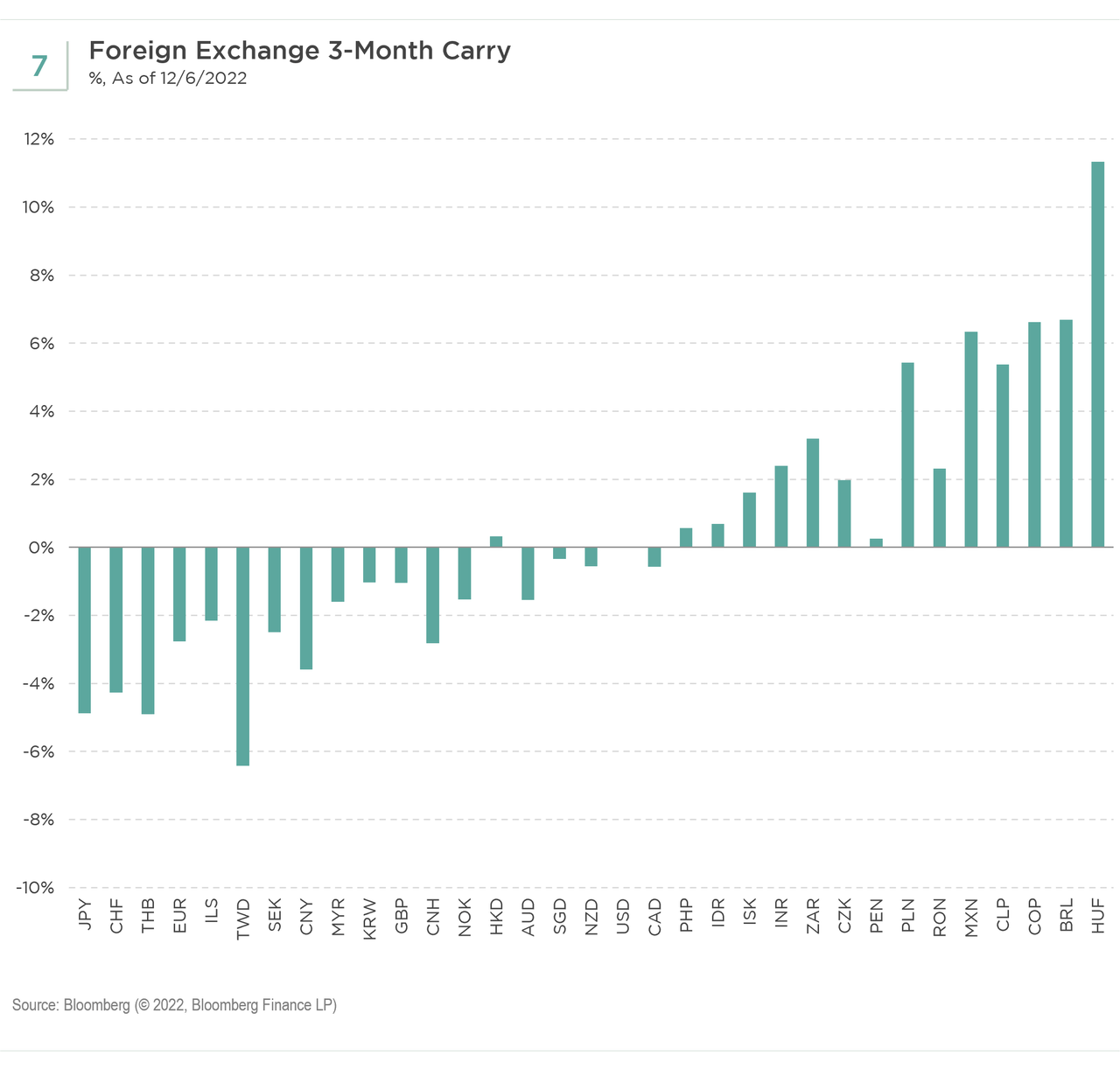

- The level of U.S. interest rates is significantly higher than nearly all developed markets, and above a number of emerging markets as well. While the yield spread will narrow, the U.S. dollar will offer higher carry for quite some time (see Figure 7).

- Moreover, the Fed will continue to pursue a contraction in its balance sheet in 2023, which is constructive for the U.S. dollar.

- Globally, most leading indicators suggest the world economy is likely to weaken through much of 2023. The dollar normally benefits from safe-haven flows when global demand weakens.

- And lastly, while the cyclical outlook for the U.S. is deteriorating, it is unclear whether the structural outlook has deteriorated. The U.S. remains a significant global leader in technology, which has been amplified by reshoring trends, and energy, supported by LNG exports to Asia and Europe. Longer-term capital flows will continue to offer some support to the U.S. on this basis.

Overall, the powerful rally in the dollar in 2022 was driven by an alignment of factors that will not persist in 2023. The greenback is expensive, and relative growth prospects point to a weaker dollar next year. Relative monetary policy will also tighten more outside the U.S., notably in Europe, and possibly in Japan as well. However, the Fed is unlikely to start easing monetary policy soon, and, hence, the positive carry offered by the U.S. dollar will offer some support to the greenback. Balance sheet contraction will further diminish the supply of dollars, also providing support to the currency. In conclusion, the dollar has likely started a peaking process. However, a sustained decline in the dollar will ultimately require the Fed lowering interest rates, the end of quantitative tightening (QT), and some expectation of improvement for the global economy, notably outside the U.S.

Emerging Markets Outlook: Nearing a Turning Point

By Michael Arno, CFA

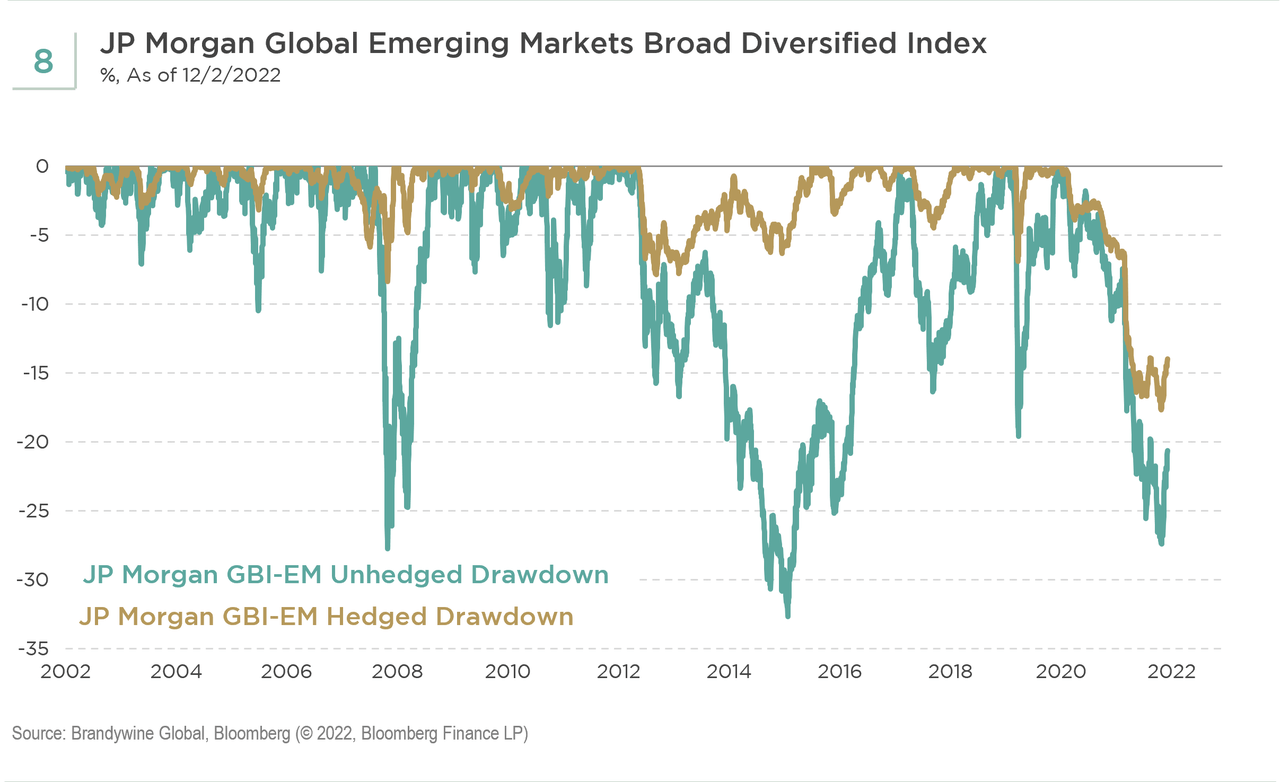

Emerging markets faced a multitude of headwinds in 2022, including tightening of U.S. financial conditions; persistent inflationary pressures both from past COVID-related fiscal impulses and new food and energy price shocks; and continued fallout from China’s zero-COVID lockdowns and deep housing market contraction. This environment resulted in a 20% drawdown for the JPMorgan Global Emerging Markets Broad Diversified Index (see Figure 8). Country performance within the index varied widely, from approximately +17% in Brazil to -40% in Hungary.

From a regional perspective, Central European markets saw the steepest losses on heightened geopolitical risks and inflationary spikes driven by skyrocketing natural gas prices, leading to terms-of-trade and current account shocks. Central banks in the region responded with a combination of rate hikes and currency intervention measures. In Latin America, performance was mixed with Brazil and Mexico outperforming on relative basis while Chile and Colombia suffered double-digit losses amid challenging domestic politics and widening current account deficits. Latin American central banks have been among the most aggressive, bringing policy rates to levels not seen in two decades to fight inflationary pressures and stabilize their currencies. Asian central banks avoided large increases in policy rates, instead managing the pace of their currency depreciation via currency interventions. However, this approach led to large declines in their foreign currency reserves.

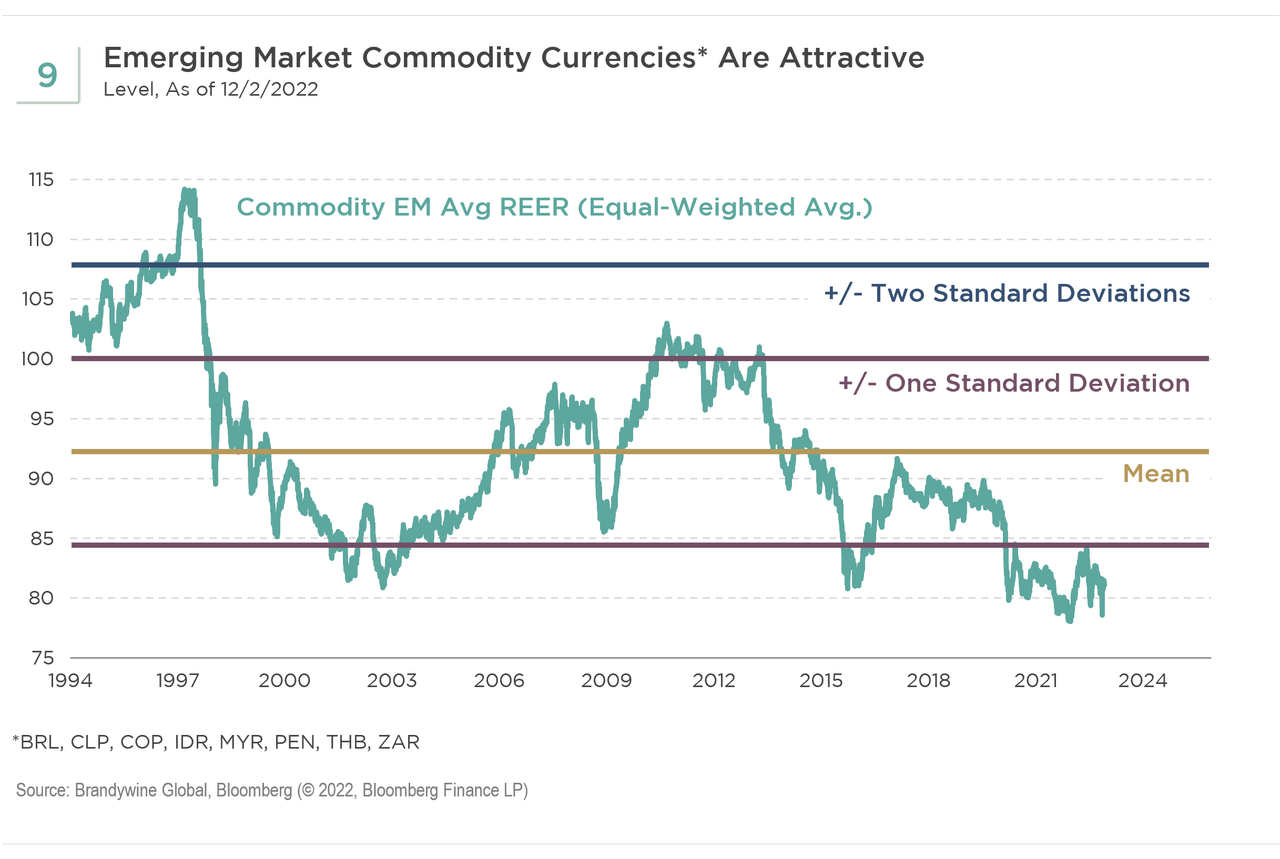

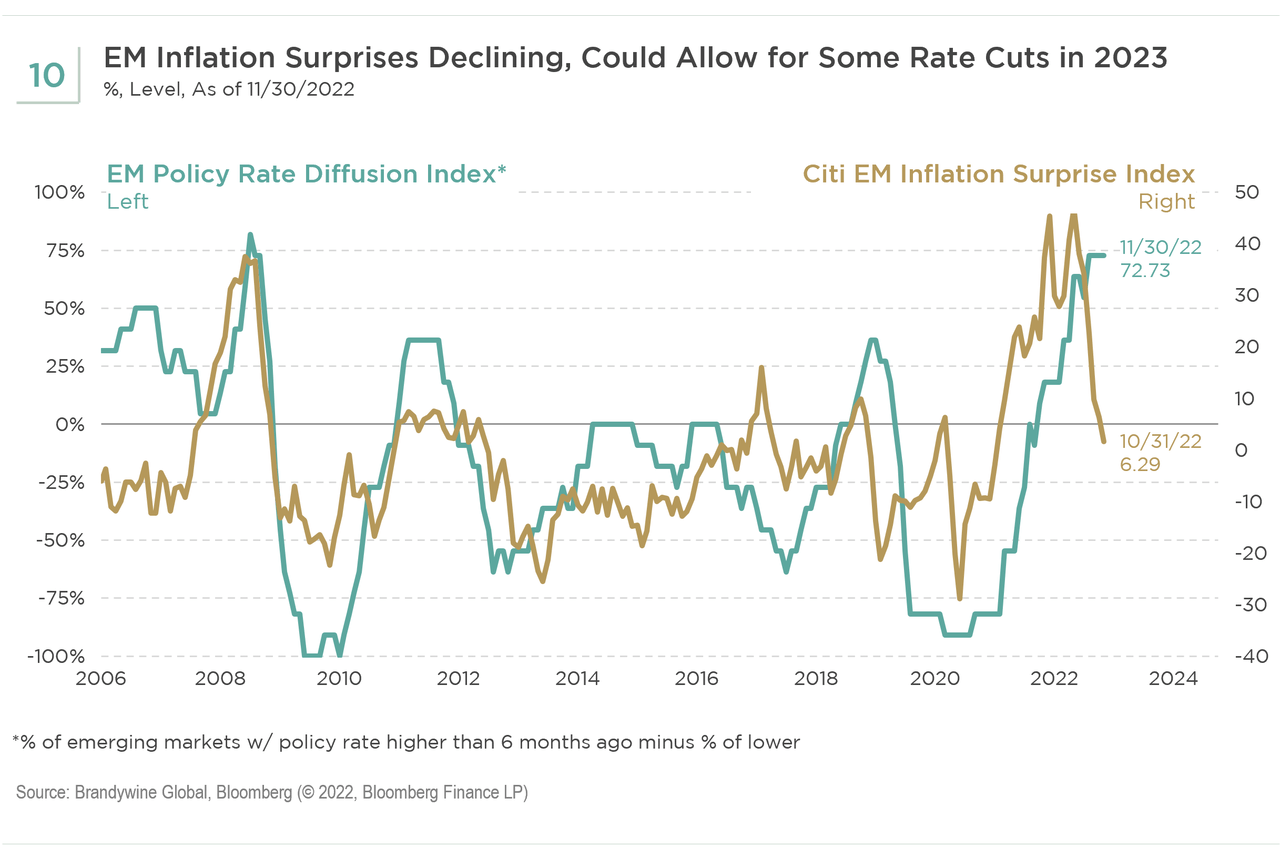

As we wrote in August, we believed then and still believe today that we are nearing a turning point in emerging markets (EM). The Fed will likely be ending its rate-hiking cycle in the coming months following a record pace of increases in 2022. While it will take time to return to the 2% inflation target, we see several signs that U.S. inflation is decelerating—particularly in the housing and auto sectors. With U.S. relative monetary policy tightening set to peak coupled with decelerating U.S. growth outperformance, we believe the dollar likely will weaken in 2023. A weaker greenback will allow for some stability in EM currencies, which we think are broadly undervalued (see Figure 9). Stable-to-appreciating currencies will be supportive to EM inflation, which we think has likely peaked. Inflation surprises continue to fall from their multi-decade highs (see Figure 10), and weaker energy and food-related commodity prices over the last few months are taking pressure off inflation in a number of markets.

EM currency markets will likely be more dependent on the outlook for global growth in 2023. If the dollar corrects lower as inflation retreats and the U.S. economy decelerates but avoids a bust, the world economy could be in better shape by the end of next year. However, the clear risk to this outlook is the Fed, which is unlikely to start easing monetary policy anytime soon and continues to contract its balance sheet. Asia currency market performance will be influenced by export growth and tourism flows. Given our view that China will likely shift toward a more viable long-term COVID strategy, we believe tourism flows will see significant recovery in neighboring countries. While we are likely to see a pick-up in China in 2023, we will be monitoring the composition of domestic growth and how that will impact various EM markets.

Energy challenges remain in Europe; however, elevated storage levels and a warmer start to the heating season could allow the region to manage through the winter. We believe the odds are rising for some type of détente between Russian and Ukraine in 2023. These two factors will be key for the Central Europe, Middle East, and Africa (CEMEA) regional currency market.

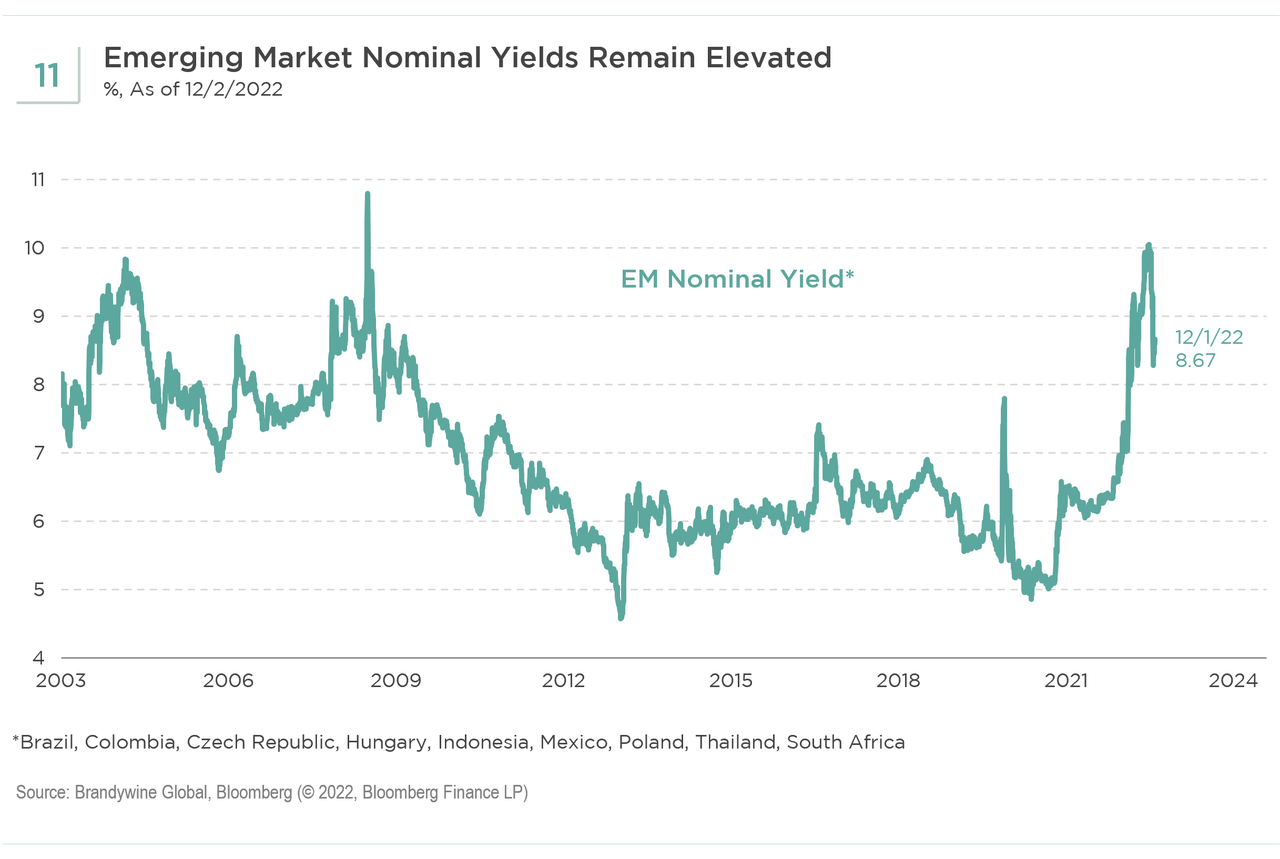

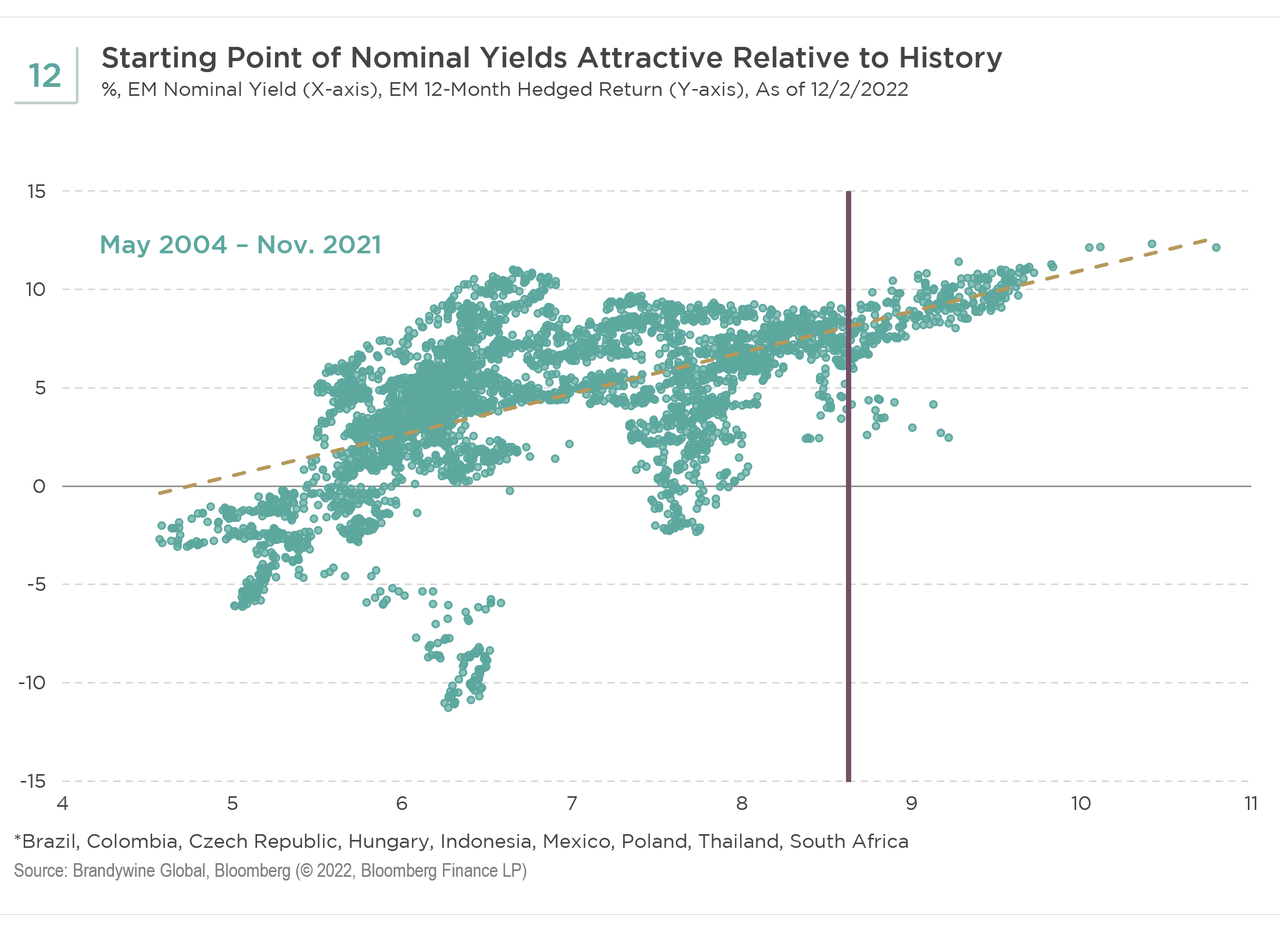

While the heavy election calendar in Latin America is over, we did see a presidential shift to the left across all major markets; however, split Congresses may put some constraints on these leaders, requiring them to move more to the center. Moderating policy, fiscal prudence, and current account adjustments would be supportive of Latin American currency markets. Although the 2023 outlook is complicated and fragmented, compelling nominal yields today (see Figure 11) coupled with disinflationary progress over the coming months could mean local EM may not be so negative (see Figure 12).

Global Credit: Attractive Valuations and Fundamentals

By Brian L. Kloss, JD, CPA

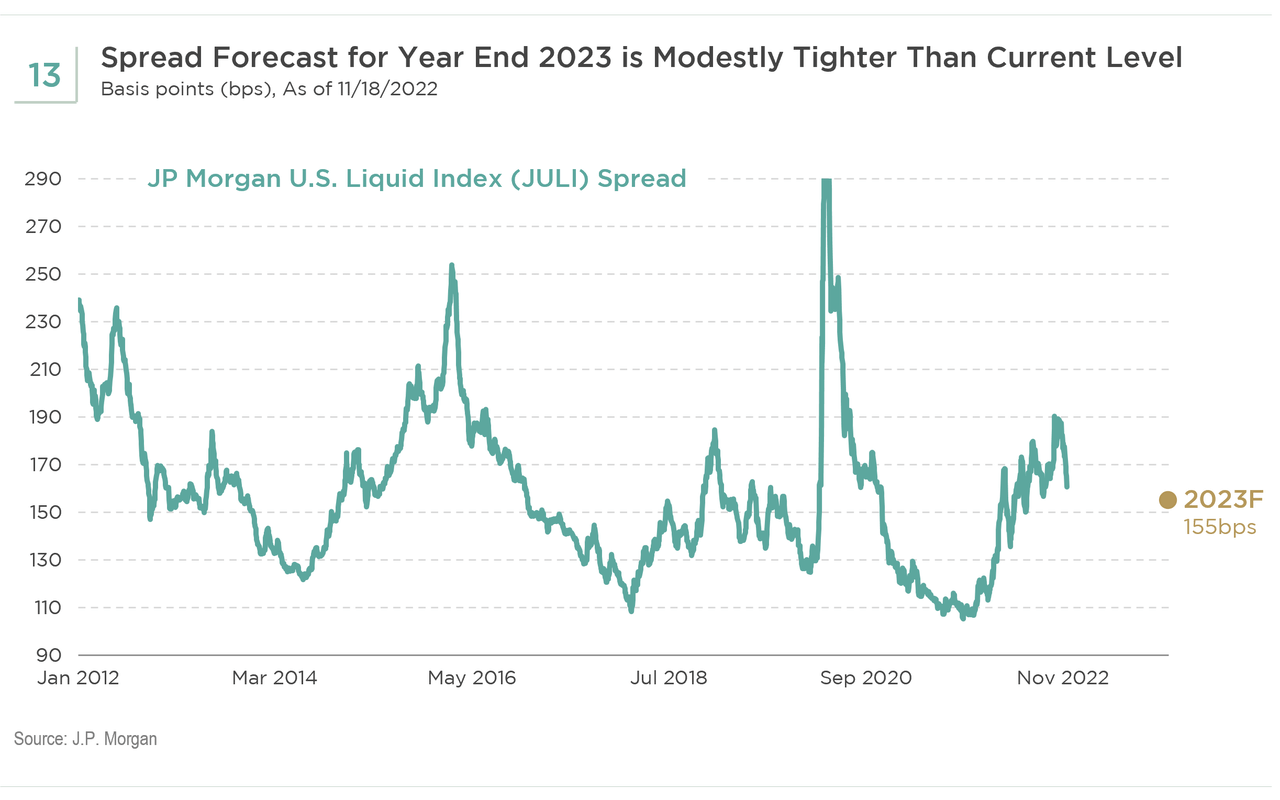

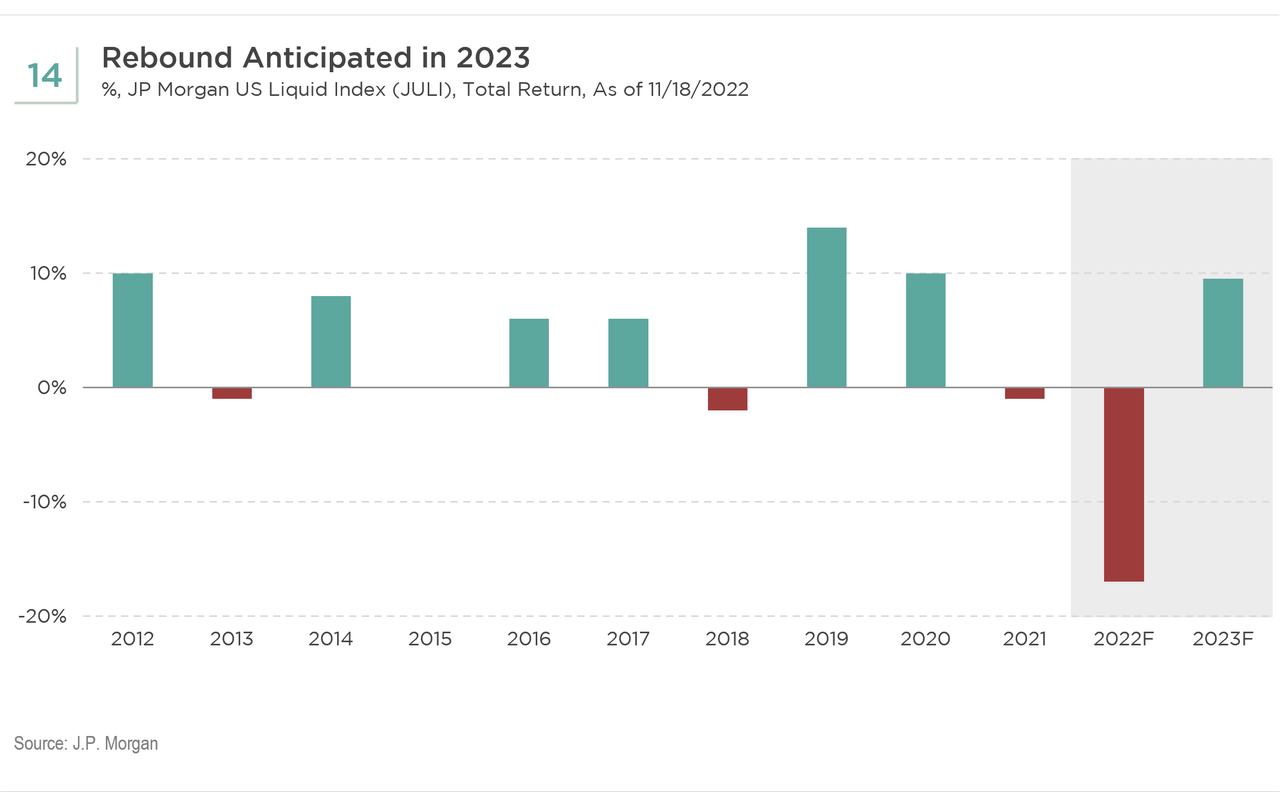

After one of the worst years for fixed income assets, investors would be remiss not to caveat the discussion around the outlook for 2023 with all the risks that abound and their potential to inject volatility into asset prices next year. However, offsetting the hurdles bond investors will be facing are attractive valuations for global credit assets. Investors must contemplate the starting point in terms of price, yield, and spread relative to the economic outlook. And today, that starting point is quite compelling given the fundamental backdrop, which includes leverage ratios at manageable levels and management teams focused on challenging consumer environments. Hence, we expect a rebound for corporate bonds in 2023 (see Figure 13 and Figure 14). Again, there will be sectors that need to be avoided, and specific credits that might be impaired. However, broadly speaking, today offers a very attractive staring point, i.e., the “bond math” works for the investor. Furthermore, if any macroeconomic headwinds turn favorable, such as inflation peaking, China’s zero-COVID policy loosening, or Ukraine/Russia tensions easing, investors may even have a tailwind at their backs.

In the short term, there will still be volatility heading into 2023, so positioning somewhat defensively remains prudent. Our focus is on companies that have been able to strengthen their balance sheets during the pandemic, have strong management teams, and demonstrate fundamentally stable businesses. In particular, we favor debt of companies with healthy balance sheets and sufficiently dominant positions in their markets to be able to pass on any further price increases. These corporate credits may offer yields that are attractive relative to the underlying risk. However, as the global monetary path and business cycle become clearer, we plan to rotate into more opportunistic sectors, including cyclical sectors and some emerging markets, specifically from China, Brazil, and Mexico, as well as assets with duration.

U.S. Credit: Case for High Yield

By Bill Zox, CFA and John McClain, CFA

During the first half of 2022, both U.S. high yield and investment grade corporate bonds performed poorly with roughly the same negative total return, although much better than equities. Higher Treasury yields and wider credit spreads contributed to a doubling of the yield in both credit markets during the first half of the year. Since mid-year, the two markets have diverged with the ICE BofA U.S. High Yield Index positive by about 4% and the ICE BofA U.S. Corporate Index (investment grade) negative by about 2%. The 5-year Treasury yield, which is more relevant to high yield, and 10-year Treasury yield, which is more relevant to investment grade corporates, have increased by about 88 basis points and 72 basis points, respectively, since mid-year while credit spreads narrowed.

One reason for the divergence in returns between U.S. high yield and investment grade corporates since mid-year is that high yield is about 40% less sensitive to rising interest rates, based on the duration of the high yield index relative to the investment grade index. Another reason is the materially higher yield—or carry—of the high yield index compared to the investment grade index at mid-year: close to 9% compared to a bit above 4.5%. As we write this commentary, the differential has decreased by about 130 basis points largely due to a higher yield on investment grade corporates.

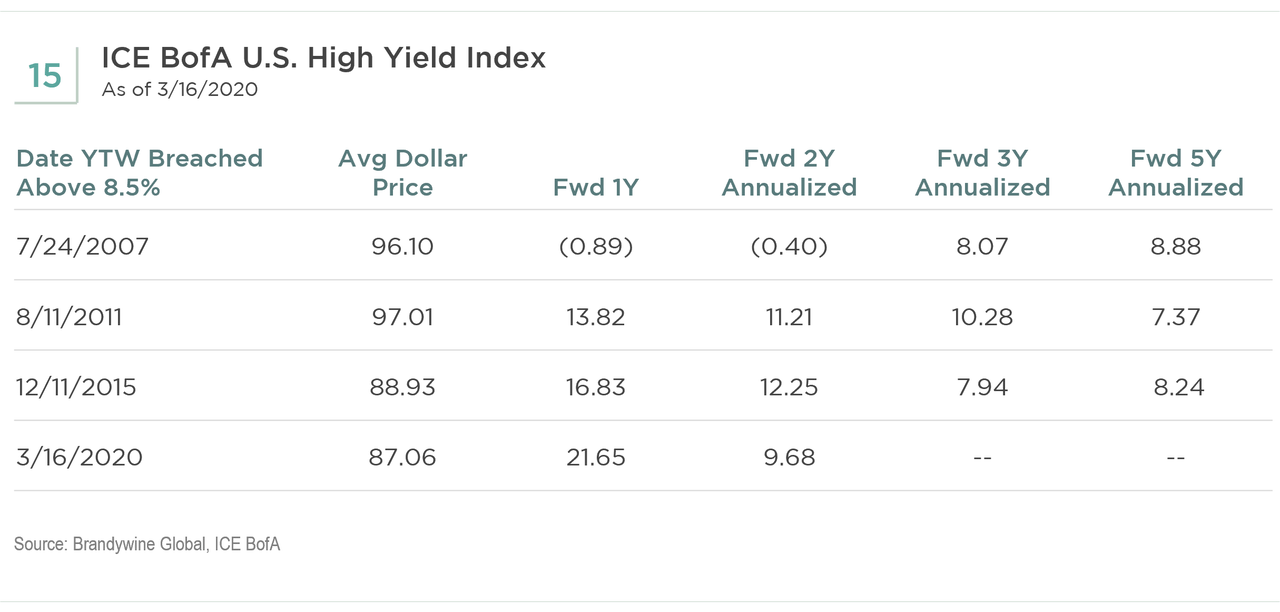

For the long-term investor, the 8.5%+ yield of U.S. high yield has historically been a good starting point, and we expect the same this time. The table below (see Figure 15) shows U.S. high yield index forward returns in prior cycles from the date that an 8.5% yield was first breached.

We also show the average dollar price of the index on the date that the 8.5% yield was breached. The dollar price now is slightly lower than when 8.5% was first breached in March 2020. When high yield is at or above 100 cents on the dollar, as it was at the beginning of the year, the upside price potential is minimal compared to the downside price risk. At a mid-80s dollar price, the upside versus downside potential is much more favorable as high yield has historically bottomed in the mid-70s to mid-80s with the notable exception of the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) of 2008 when high yield bottomed in the 50s.

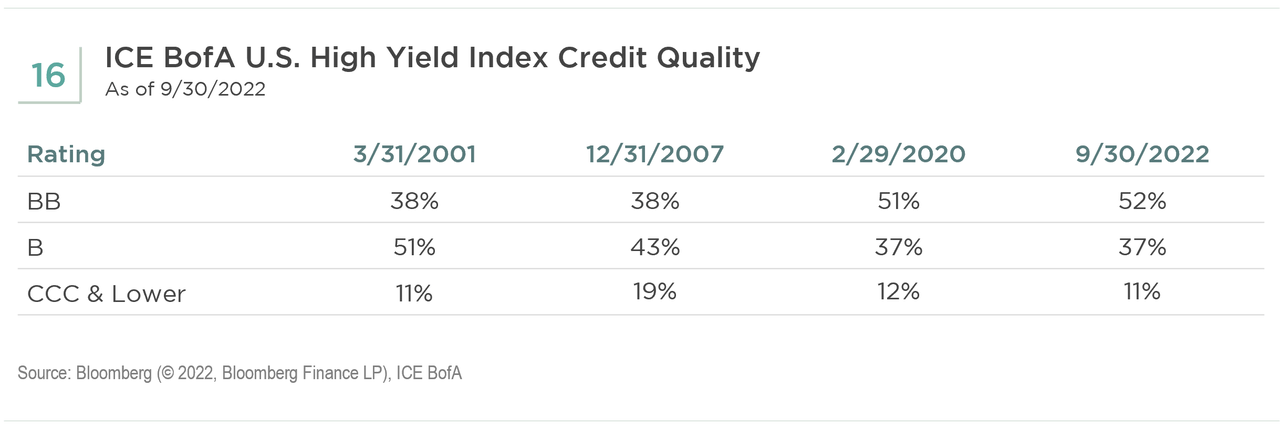

Since mid-year, the high yield credit spread has been in the 400-600 basis point range. For a number of reasons, we believe that range is comparable to 600-800 basis points in prior cycles. As shown in the table below (see Figure 16), the credit quality of the high yield market is much higher than it has been historically. The lower-quality issuance is now more in the leveraged loan and private credit markets. Also, high yield bonds are fixed-rate obligations that are being serviced with now-inflated assets and cash flows, which should result in lower default losses and credit spreads than during disinflationary recessions. While the probability of recession is high in 2023, we believe a stressed-case scenario for high yield defaults over the next few years would be more like the experience in the recession scare of 2015-2016 than the recessions in the early and late 2000s. That would mean defaults could increase from less than 2% currently to a cumulative 10% or so over the next few years.

Policymakers are faced with an extraordinarily difficult task of containing extremely high inflation under unique and highly uncertain circumstances. Corporate managements, on the other hand, have several quarters to adapt and prepare for a likely recession in 2023. The post-GFC, ultra-low borrowing environment allowed managements to massively reward shareholders with dividends and share repurchases. Leverage was allowed to rapidly expand as valuations exploded and interest expense remained low. We are in the early innings of a radical shift with many corporate managements turning their focus to reducing leverage and interest costs to prepare for the return of a normal cost of capital rather than the ultra-cheap capital of the post-GFC period. With bond prices well below 100 cents on the dollar, best-in-class managements are taking advantage of a generational opportunity to improve their equity returns through discounted bond buybacks.

In our view, it is too late in the cycle for CCC-risk but there are opportunities in the B and BB-rated parts of the high yield market where the yield and dollar price are compelling compared to the risk of default loss. We also see opportunities to swap from the BB-tier of the high yield market into the BBB-tier of the investment grade market without giving up spread or yield. This situation is the result of dedicated high yield investors who want to upgrade their portfolios and are paying up for BBs. Meanwhile, dedicated investment grade investors who want to upgrade their portfolios are shying away from BBBs. In particular, we favor cyclical BBB risk at attractive valuations over defensive BB risk at rich valuations.

Structured Credit: Cheaper, Safer Alternatives

By Tracy Chen, CFA, CAIA

The Fed’s fast-paced monetary tightening is due to leave a trail of debris from burst asset bubbles in 2022 and a looming recession and credit events in 2023. Whether or not we have seen peaks in inflation, Fed hawkishness, and China’s zero-COVID control and property market tightening will determine the performance of various asset classes.

As one of the most interest rate-sensitive sectors of the global economy, housing markets across most developed economies are going through various recessions because of interest rate hikes and poor housing affordability post-COVID. Unlike in other developed markets, the U.S. housing market is still supported by a tight labor market, the lock-in effect of low fixed mortgage rates for existing homeowners, tight mortgage underwriting, low leverage in the mortgage sector, and low housing supply. We believe we can avoid a severe housing downturn like the one in the Global Financial Crisis (GFC). U.S. consumers are still in spending mode with enough residual excess savings to last another one to two quarters, and their balance sheets remain healthy with decent home equity and low financial obligation ratios.

Given the above fundamentals, we see abundant attractive investment opportunities in the structured credit market, offering cheaper but safer alternative in 2023:

- Agency Mortgage-Backed Securities (MBS)MBS valuations are very attractive, and convexity is near the best levels due to the out-of-money status. Please see our recent blog for more information on the opportunities in this sector.

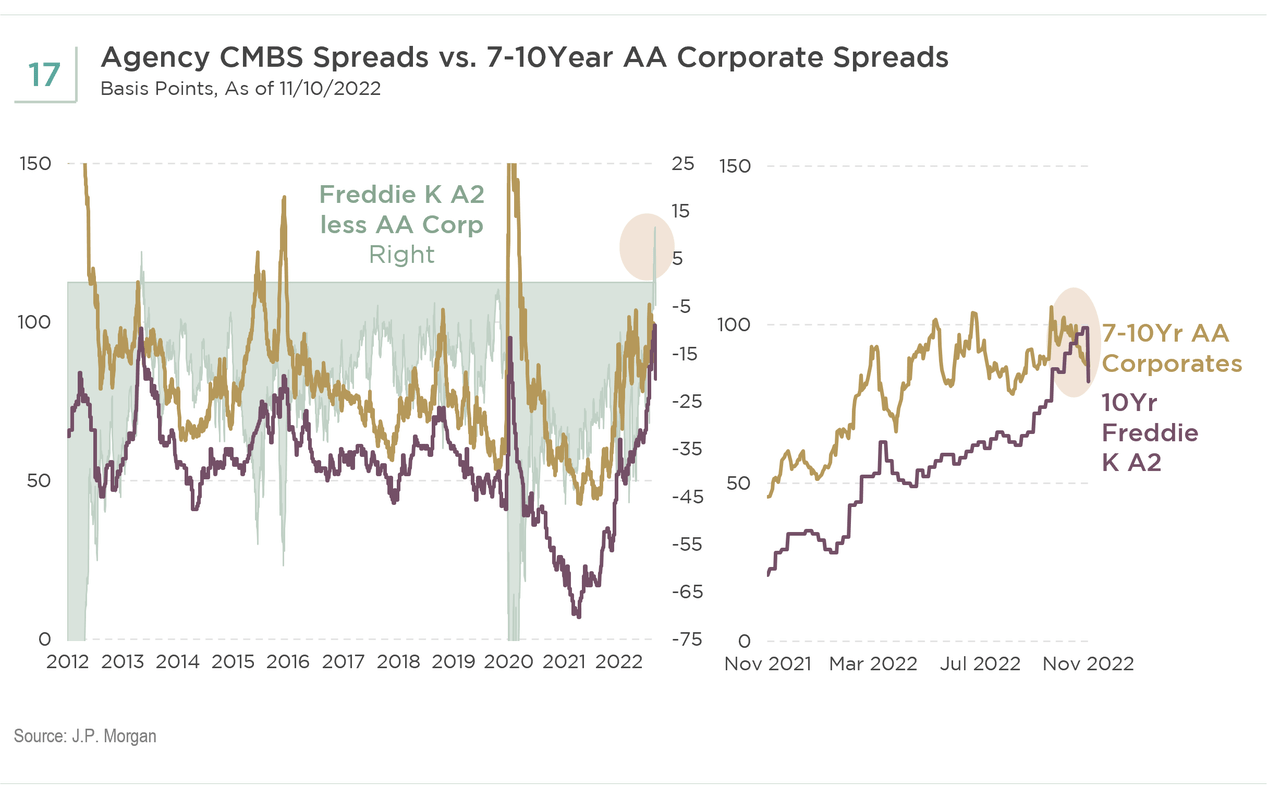

- Agency Commercial Mortgage-Backed Securities (CMBS)Government guaranteed agency CMBS with call protection are now cheaper than 7 to 10-year AA corporate bonds, a rare case in history (See Figure 17)

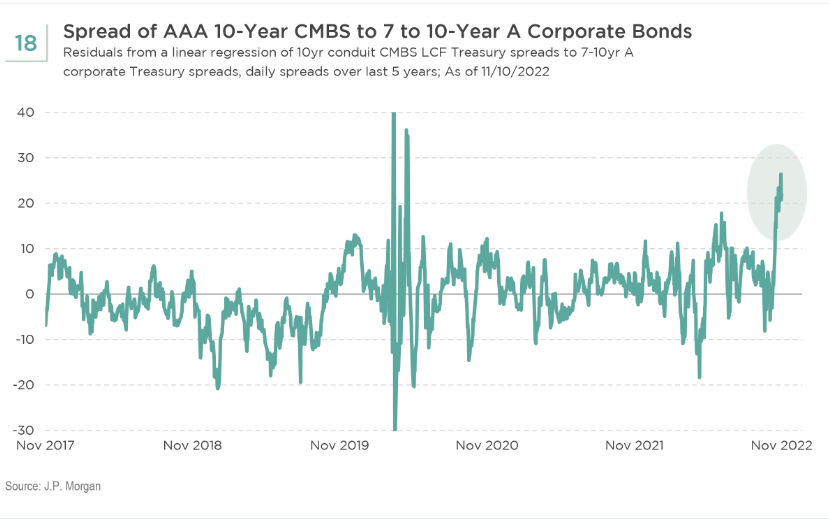

- Non-agency CMBSCurrently, AAA-rated conduit CMBS look cheaper than similar duration single-A corporate bonds (See Figure 18)

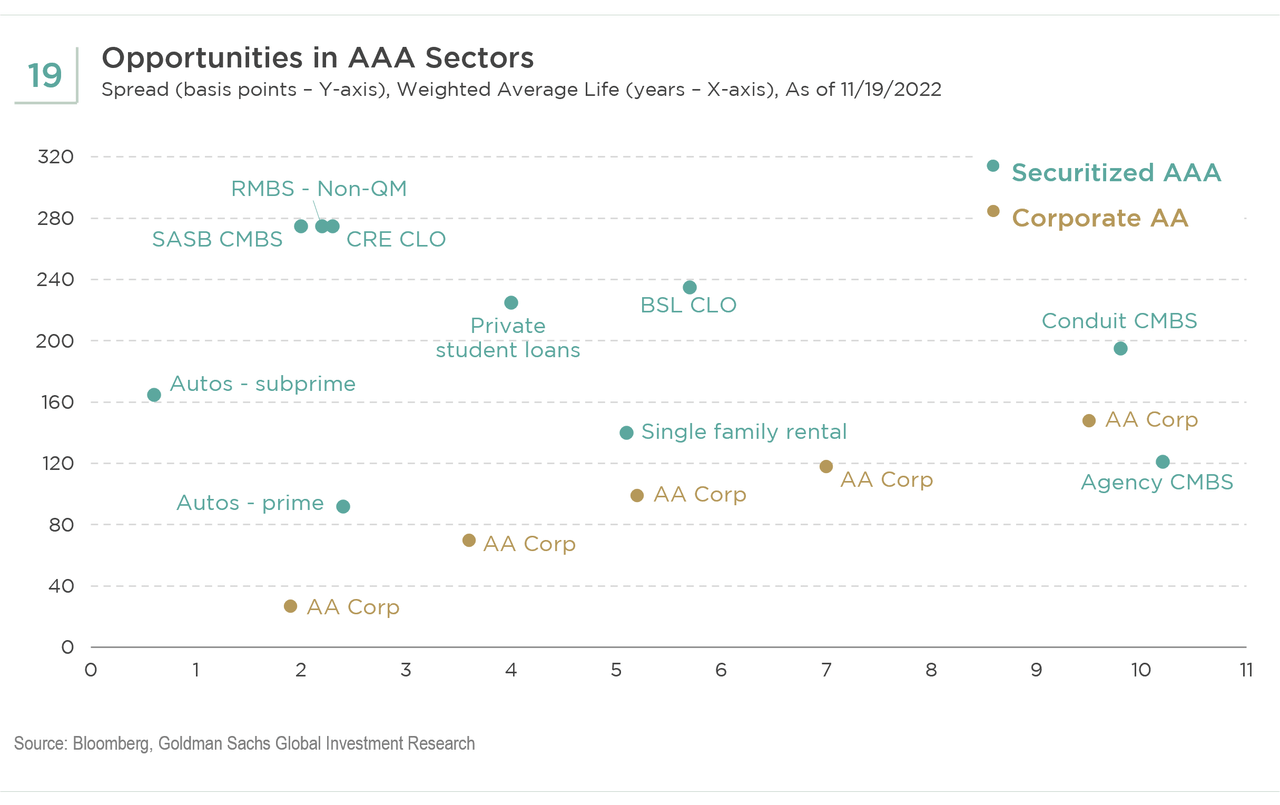

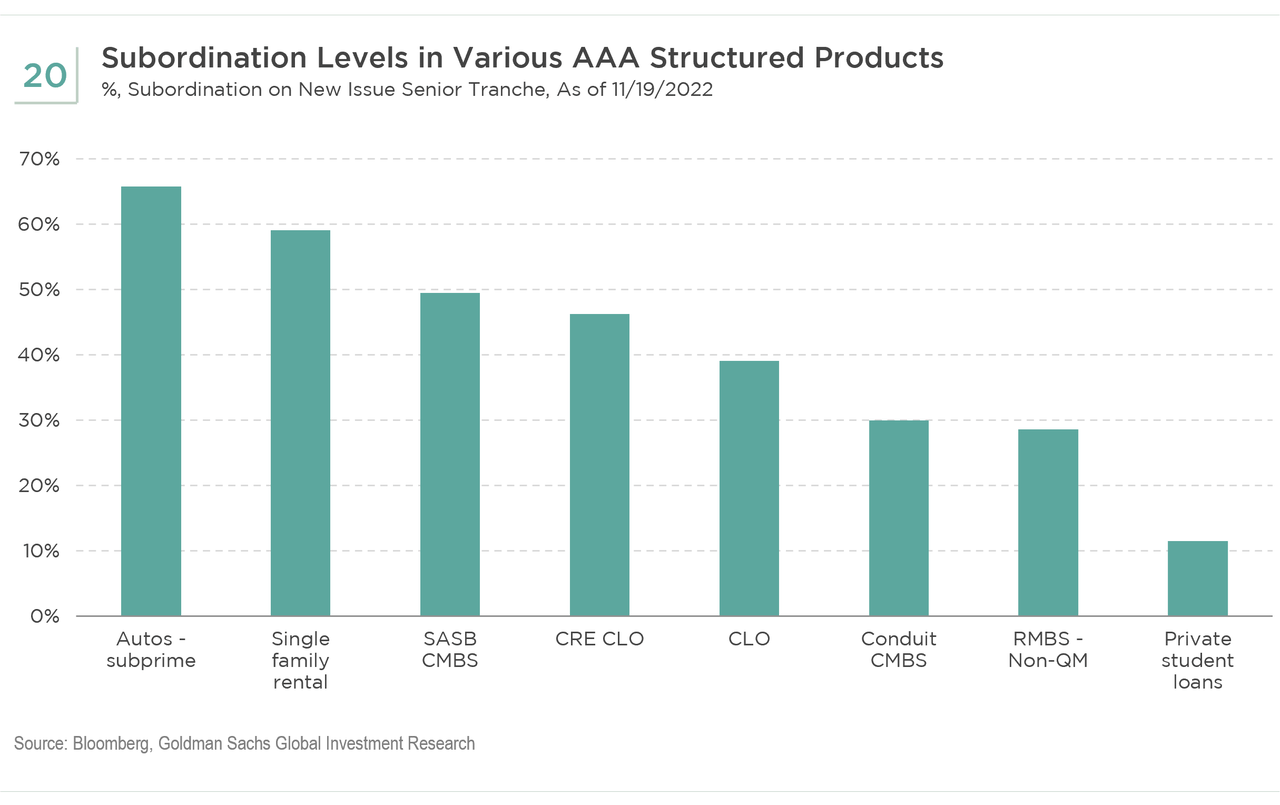

There are also attractive opportunities in other AAA-rated sectors like AAA collateralized loan obligations (CLO), AAA non-qualified mortgage securities, AAA commercial real estate (CRE) CLO, AAA subprime auto asset-backed securities (ABS), investment grade-rated credit risk transfers (CRT), etc. The levels of subordination provide good credit support for AAA structured credits (see Figure 19 and Figure 20). Investors with larger risk appetites also can find opportunities in BBB or equivalent CLO, CMBS, or CRT, which offer double-digit yields that help compensate for the credit risks.

With high-quality structured credit having cheapened so much, we do not need to take excessive credit risk to achieve decent returns. As recession risk looms in 2023, we believe these structured credit sectors should outperform during an economic downturn with minimal credit risks. Historically wide spreads compensate for many risks. While these assets could cheapen further if the Fed overtightens and Treasury rates climb significantly higher, we think these structured credit investments should pay off over the medium to long term. We believe investors should consider taking advantage of these opportunities and the potential for attractive long-term returns.

Global Equities: Expectations versus Reality

By Sorin Roibu, CFA

Long-term investment returns are decided by the intersections of expectations and reality. To be more exact, alpha is generated when overly negative expectations are met with benign or positive reality. For global equities, the reality in 2022 has been worse than expected, hence the resulting market performance.

The question we think investors should be asking is: Will things be better or worse a year from now than what is expected? That will be the deciding factor of investment returns. We would argue that negative sentiment has generally caught up to reality, and in many parts of the world it has even overshot.

When we look around the world, we find areas where negative sentiment clearly is excessive and is more than reflected in valuations. These include China, Europe, and the Japanese yen. We are overweight and expect the outcome to be better than what is reflected in market estimates and valuations.

On the opposite end of the spectrum is the U.S., which remains our biggest country underweight. We think there is more bad news to come, and market expectations and valuations are still too optimistic. It is clear to everyone, except the central bankers, that the Fed is on course for another major policy error. They may succeed in curing inflation but are also likely to seriously hurt the patient in the process. The Fed is exhibiting all the behavioral signs of managing career risk, where the goal appears to be saving face after the numerous policy blunders rather than making calculated decisions based on facts. We are content to stay defensive and underweight the U.S. until valuations offer a greater margin of safety, or the Fed alters its monetary policy.

U.S. Equities: More Skepticism, Less Complacency

By Patrick S. Kaser, CFA and Celia R. Hoopes, CFA

The U.S. equity market rallied through October and early November. Many companies “beat” earnings estimates, and on November 10, a weaker-than-expected CPI print sent higher-beta stocks full steam ahead. Fear of missing out (“FOMO”) is alive and well with investors desperate for any line of sight, no matter how murky, toward an eventual pause from the Fed. We believe the market is being far too complacent. Indeed, S&P 500 earnings were forecasted to grow through the end of June with earnings revisions only falling 3.8% thus far. In a typical recession, earnings revisions fall on average 20%. Valuations for the overall market do appear compelling with the price-to-earnings (P/E) multiple of the S&P 500 trading at 18x and the NASDAQ trading north of 24x.

History suggests many possibilities, but we will highlight just three:

- The market does not normally bottom before the Fed pauses.

- Inflation takes more than three years to normalize.

- Recessions happen after tightening cycles of this magnitude.

Fed officials continue to talk about the federal funds rate heading to 5% or higher, albeit with a slowing pace. They also continue to emphasize that they do not want to pause too soon. These attitudes are both sensible as it comes to inflation and likely to lead to recession. Inflation will slow, for sure, but to what level? The labor market is tight, and unemployment will almost certainly rise as Fed tightening continues apace. Earnings estimates should come down, and stocks are likely to go on sale as recession approaches. Maintaining a neutral stance and building a shopping list seem like sensible approaches in U.S. equity markets; a willingness to be adaptable to changing conditions will be key to managing portfolios. The time to be bullish will come, but we have seen several bear market rallies that have not yet dissuaded the believers. We need more skepticism—and lower prices—to go more aggressive ourselves.

Editor’s Note: The summary bullets for this article were chosen by Seeking Alpha editors.

Be the first to comment