John M. Chase/iStock Unreleased via Getty Images

It’s been just under two months since I wrote my cautious piece on Norfolk Southern Corporation (NYSE:NSC), and in that time the shares are down about 16.3% against a loss of 14.3% for the S&P 500. This creates some tension in me, because the shares are now much cheaper, so they may be worth buying. After all, a stock that was too expensive at $266 may be a bargain at $221. I’ll make this determination by looking at the current valuation and comparing it to “normal” history. Also, I think it would be worthwhile to review the “Stock v 10-year Treasury Note” analysis that I ran previously, as things are much different now. Finally, I want to write about the puts I wrote previously for a few reasons. Obviously the most important of these is that it gives me an opportunity to brag once again about the $50 per share that I’ve earned writing puts. Less importantly, my experiences here may offer you a cautionary tale. I want to focus in on the September puts with a strike of $200. I originally sold these for $2.10 and they last traded hands at $6.90, so it’s an “emotional” trade so far.

Finally, I think we make investing harder than it needs to be when we don’t apply some sort of rigorous, historically informed analysis about valuations. While Norfolk Southern shares are much cheaper now than they were previously, “cheaper” is not the same thing as “cheap.” Had someone bought at a price $15 below the level at which I most recently eschewed these shares, for instance, they’re still down about 12%.

So, in some sense, we have to pay less attention to price and more to valuation. This doesn’t mean that I think price is irrelevant. Far from it. I think the stock price itself is a great source of information that’s not really exploited by most investors, but when it comes to valuations, it’s only half the story. The stock price is relevant only as it relates to “backward-facing” measures of value (e.g., PE multiples) and current measures of value (e.g., dividend yield).

Thus, I don’t want to fall into the trap that many people seem to of “buying the dip,” a move that expresses a faith in the market to rescue us as it carries shares higher. Such faith in a capricious market is misplaced in my experience, and so I’ll buy only if the shares are sufficiently cheap.

We finally come to the “thesis statement” portion of the article, where I give you the highlights of my thinking in a nice, condensed package, so you won’t be obliged to wade through the entirety of my screed. This is one of the many “value adds” that I selflessly offer to you people. You’re welcome. Anyway, I continue to think this is a wonderful business, with a well-covered dividend, that would be a great stock to own at the right price. Earlier I wrote “I’ll buy only if the shares are sufficiently cheap.” Spoiler alert: They’re not. They’re neither cheap enough relative to alternatives available nor to their own history. For that reason, I would recommend investors continue to avoid them. That said, I think $200 would be a decent entry price, and so I would recommend selling the September puts with that strike. Either the investor will be obliged to buy at a great adjusted price, or they’ll receive very generous compensation from the options market for indicating a willingness to do so. I won’t be able to follow on this trade, as I already have sufficient exposure to these puts, but I would recommend the people who are just joining this party avail themselves of this opportunity.

The Stock

I’m about to tread over very old ground. If you read my stuff regularly for some reason, you’ve seen me make the point that a stock is distinct from the business many, many, many times before. If you’re one of the new people, let me make the point that a stock is very different from the business. Further, the stock is often a very poor proxy for the business that it supposedly represents. A business buys a number of inputs required to haul heavy products from one place to another, and then sells those transportation services at a profit. The stock, on the other hand, is a traded instrument that reflects the crowd’s aggregate belief about the long-term prospects for the company. The crowd changes its views about the company relatively frequently which is what drives the share price up and down. Added to that is the volatility induced by the crowd’s views about stocks in general. “Stocks” become more or less attractive, and the shares of a given company get taken along for the ride. Although it’s tedious to see your favourite investment get buffeted because the asset class of “stock” goes in and out of favor, within this tedium, we have opportunity. If we can spot discrepancies between the price the crowd dropped the shares to, and likely future results, we’ll do well over time. It’s typically the case that the lower the price paid for a given stock, the greater the investor’s future returns. In order to buy at these cheap prices, you need to buy when the crowd is feeling particularly down in the dumps about a given name.

If you thought I was going to make this point theoretically and leave it at that, you’ve got another thing coming, I’m afraid. If I see an opportunity to belabour a point, you gotta know I’m going to take it. I’ll push the above point further by using Norfolk Southern stock to demonstrate. The company reported its latest quarterly results on April 27. If you bought that day, you’re down about 15.6% as of Friday’s close. If you waited until May 19, to pick a date completely at random,, you’re down only 2.4%. Not enough changed at the firm over such a short time to justify a 13%+ variance in returns. So, the stock is a very volatile thing, and the person who buys cheaper does better or “less badly.”

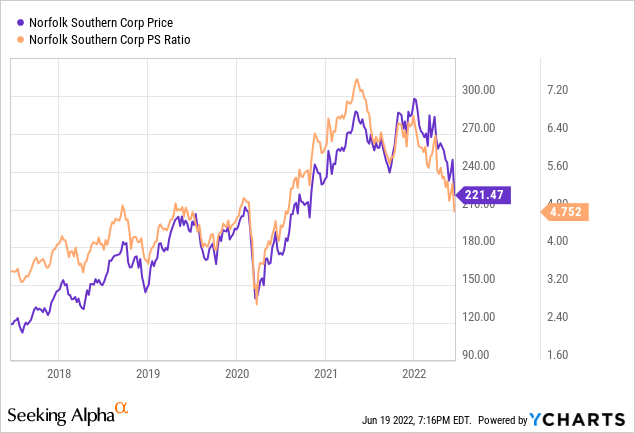

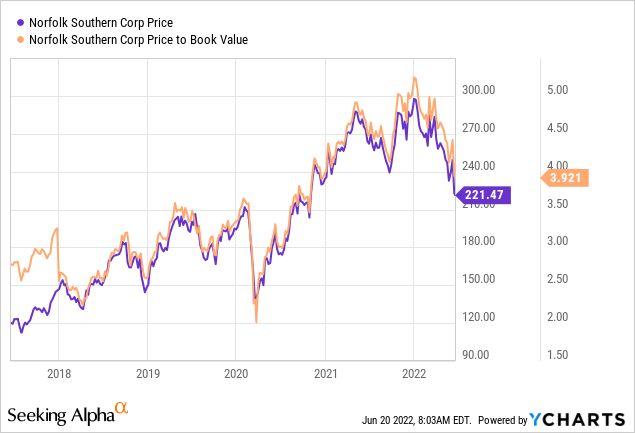

Anyway, as my regulars know, I measure the relative cheapness of a stock in a few ways ranging from the simple to the more complex. On the simple side, I like to look at the ratio of price to some measure of economic value, like earnings, sales, free cash, and the like. Once again, cheaper wins. I want to see a company trading at a discount to both the overall market, and the company’s own history. In case you haven’t kept your “Doyle’s trades” almanac up to date, I’ll remind you that in the previous article on this name, I stated that I was unimpressed by the fact that the price-to-sales ratio was floating around 5.9 times, and that the price to book was about 4.65 times.

We see from the following that the shares are about 19% cheaper on a price-to-sales basis, and the price to book is about 16.5% cheaper, per the following:

The problem here is that, although the shares are “cheaper,” they’re not “cheap” by historical standards. In spite of growing evidence of an economic slowdown, the market continues to pay more for $1 of future sales than it did in 2017, when economic growth was much more robust.

Ready To Rumble Rematch

In the domain of investing, everything’s relative, because an investor can choose to buy “X” over “Y.” In addition, when the investor buys “X,” they are, by definition, eschewing every potential “Y,” because we have only so much capital.

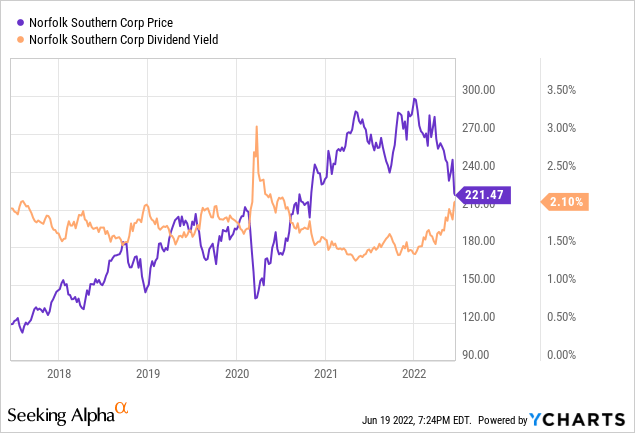

With that as preamble, let me remind readers that in my previous missive on this name, I suggested that one of the reasons the shares were unattractively priced was the fact that an investor could take their capital and just as easily buy a 10-year Treasury note, that was at the time yield 2.85%, when the dividend was a paltry 1.9%. Fast forward less than two months and both the dividend yield and the yield on the 10-year note are now about 40 basis points higher.

Previously, I concluded that, in order to be indifferent between the stock and treasury bond, the stock investor needed to assume that the stock would generate a 9% capital gain from current levels. Put another way, the Treasury investor was going to receive 9% more cash flows on their investment than the buyer of the stock with a dividend attached.

My thinking was informed by a few uncontroversial assumptions:

-

That the Treasury note, for all of its faults, is risk-free in the sense that you know what you’re going to get in 10 years. The same can’t be said of stocks.

-

That the investor is able to buy either asset and is seeking to maximize their risk-adjusted returns.

-

Given the different tax treatments and the multiplicity of tax brackets, etc., that this analysis happens under the protective umbrella of a 401-k, or (very strangely named) IRA.

I’ve conducted the same analysis again, and I’ve posted the results below for your enjoyment and edification. The results are, unexpectedly, largely the same. The Treasury buyer enjoys between 7% and 10% more cash than is offered by the dividend. The fact that the stock dropped precipitously since I last wrote about this business further highlights the relative risk in my view.

Given everything we’ve seen so far, I would recommend that investors not be seduced by the recent drop in price and refrain from buying at current prices. Just because I don’t want to buy at current levels, though, doesn’t mean I see no value here. I’d certainly be willing to buy at the right price, which is where options come in.

My Short Puts

In my previous missive on this name, I took great delight in pointing out that I’ve made about $50 per share in this name by selling options on it over the years. It’s this tendency to shout about my few successes while trying to ignore my many failures that are caused my social life to hit the depths that it has.

Anyway, I’ve done well by selling people the right to sell this stock to me at a price that I found attractive. When the shares were trading at $260, for instance, I found $200 to be a very attractive price, which is why I sold the September puts with a strike of $200. If the shares remain above $200 over the next several months, I’ll simply pocket the premium. If the shares fall, I’ll be obliged to buy, but will do so at a price that lines up with a 2.4% dividend yield. Please note that this would be quite a high yield by historical standards. As I wrote at the beginning of this article, I made $2.10 per share selling these, and they last traded hands at $6.90. I’ve got enough exposure to this stock, so I’m not going to sell more, but if you’re just tuning in, I would strongly recommend selling the September puts with a strike of $200, because I (still) consider this to be a “win-win” trade. If the shares remain above $200 over the next two months, the investor will pocket a 3.45% yield. This is not a bad yield for three months of what can only very loosely be described as “work.” If the shares fall below $200, the investor will be obliged to buy but will do so at a net price of about $193. At this price, the dividend yield shoots to 2.5%, which is a level not seen since the market melted down in March of 2020, and not seen before that since 2017.

We now come to one of my favorite portions of the article. This is where I get to indulge my desire to spoil people’s happy feelings by pointing out that the phrase “win-win” is just a rhetorical device. This trade, like everything, comes with risk. I consider the risks associated with put options the way I trade them to fall into two broad categories: The economic and the emotional.

Starting with the economic risks, I’d say that the short puts I advocate are a small subset of the total number of put options out there. I’m only ever willing to sell puts on companies I’d be willing to buy, and at prices I’d be willing to pay. So, I would never advocate that people simply sell puts with the highest premia. In my view, that strategy would lead to disastrous results. So my first bit of advice is to only ever sell puts on companies you want to own at (strike) prices you’d be willing to pay. Take my word on this one, as it’s informed by the pain I felt being exercised on a company called “Gandalf Technologies” in the mid-1990s at ~$8 per share. Good ole Gandalf filed for bankruptcy in 1997. This episode offers further evidence of the phrase “too soon old, too late smart.” Anyway, never enter a strike price unless you’re willing to buy at that level.

The two other risks associated with my short puts strategy are both emotional in nature. The first involves the emotional pain some people feel from missing out on upside. To use this trade as an example, let’s assume that Norfolk Southern’s stock price goes parabolic and hits $300 per share over the next two months. It’s theoretically possible. Put writers will not catch any of the upside in the stock. So, short put returns are capped by the premium received. This is emotionally painful for some more hopeful souls than me. Thankfully for me, my expectations have been lowered dramatically over the decades (see Gandalf catastrophe above), so this isn’t really an emotional hardship for me.

Secondly, it can be emotionally painful when the shares crash below your strike price. So far whenever this has happened to me, things have worked out well over the long term, because I insist on only ever writing puts at “screaming buy” strike prices. So, be prepared to see shares fall below $200, and try to have some faith that you’re buying a great business at a decent price, and that such a trade will work out over the long term. This can be challenging for some people, and if you’re not able to ignore market prices after you’re exercised, puts may not be for you.

If you understand these risks and can tolerate them, I would recommend that you sell the September $200 Norfolk Southern puts. I think they’re a great way to reduce risk while enhancing returns. Now, you may find it strange of me to end a section on the risks of short puts by writing about the risk lowering potential of these things. I can’t imagine that you’re very surprised that I can be strange.

Conclusion

Although the shares are much cheaper than when I last reviewed this name, “cheaper” is not the same thing as “cheap.” I think the market is paying too much for $1 of sales, especially in light of the current macroeconomic environment. That said, I’m still comfortable buying this business, with its unassailable moat, at the right price. In my view, “right” is about $200 per share. I can wait for the market to drop to that level, which is troublesome because it may never happen, and because waiting is boring. Earlier, I took the alternative approach by writing puts. While I’m happy with the trade I entered previously, I think the puts are even more compelling now. For that reason, I would recommend people who are just joining this party to sell the puts above if they have the stomach for it. In one future outcome, the investor pockets just under 3.5% for three months of, uh, “work.” In the other, the investor locks in a great price on a great business, which is never a bad thing.

Be the first to comment