AscentXmedia/E+ via Getty Images

Netflix (NASDAQ:NFLX) investors look back on a difficult half-year. Overall, the shares have lost about 70% after peaking at around $700 in November 2021. I first reported on NFLX recently and outlined why I believe the company is operating in an increasingly commoditized industry. Other reasons for my rather pessimistic verdict included management’s apparent lack of a concrete plan for how it will monetize shared accounts without harming its subscriber base, and the clear signs that the company is maturing, coupled with its still growth-stock-like valuation.

The company is typically acquiring broadcasting rights from third parties to be able to offer its consumers a rich selection. However, Netflix is also increasingly investing in in-house productions, but their reception still leaves something to be desired and I suspect it will be a while before the company has earned a reputation for high-quality in-house productions.

In this article, I would like to introduce you to an emerging competitor of Netflix – Comcast Corp. (NASDAQ:CMCSA), which runs its own streaming business – Peacock – since mid-2020. I will compare the two companies and highlight their respective strengths and weaknesses. In doing so, I will show why I believe Comcast is likely to prove a more solid, but certainly less emotional investment in the future.

What Differentiates Comcast from Netflix As a Business?

While Netflix, as a pure-play streaming business, is very simple to understand, Comcast requires a somewhat more detailed explanation due to its broadly diversified business. CMCSA is a global media and technology company with three primary businesses: Comcast Cable, NBCUniversal and Sky. Comcast was originally a cable company but diversified through the acquisitions of NBCUniversal in 2011 and 2013 and the acquisition of Sky in 2018. The company has five reportable segments, namely Cable Communications, Media, Studios, Theme Parks and Sky. In 2021, Cable Communications remained the most important contributor to revenue and EBITDA, accounting for 53 % and 76 %, respectively. CMCSA’s Media segment, which includes NBC and Telemundo stations and TV channels, as well as the Peacock streaming service, was responsible for 19% of revenue and 12% of EBITDA in 2021. Comcast owns the Universal theme parks in Orlando (FL) Hollywood, California (CA), Osaka (Japan) and Beijing (China). The Theme Parks and Studios segments together contributed 6% to CMCSA’s EBITDA in 2021. 93% of Comcast’s 34.2 billion customer relationships reported in fiscal 2021 are residential, with the remainder being business customer relationships.

Taken together, Comcast can certainly be characterized as a diversified media and technology company that is increasingly trying to get its share of the streaming pie.

Peacock’s Service Compared To Netflix

Peacock is a relatively new streaming service launched in mid-2020. CMCSA struck a distribution deal with Apple (AAPL) in order to make the service available on iOS devices and Apple TV on-launch. Peacock is also available on Roku since September 2020 and – via apps – on Sony’s PlayStation 4, Samsung Smart TVs and Amazon’s Fire TVs and tablets.

In 2021, Peacock generated $800 million in revenues but an EBITDA loss of $1.7 billion, which includes content spend of over $1.5 billion. The company expects to increase its content spend to over $3 billion in 2022 and hence, Peacock will remain EBITDA-negative for the foreseeable future. The company’s strategy is to aggressively grow the service while accepting temporary losses that are easily absorbed by the rest of the business.

Compared to Netflix’s subscriber base at the end of 2021 of approximately 222 million, Peacock is still very small, with 24.5 million monthly active accounts in the United States. However, it should not be forgotten that the service was launched in mid-2020 and was only introduced very recently in the U.K. and Ireland, while other Sky territories have yet to be tapped. The aforementioned 24.5 million monthly active accounts represent about 75% of the guidance the company has provided for 2024, suggesting that the service is growing beyond expectations.

While Netflix has not yet used advertising to boost its revenue, it is a key part of Peacock’s strategy. CMCSA’s service was planned as a streaming service that offers premium content and supported mainly by advertising. During the Q4 2021 earnings call, management expressed high confidence that the advertisement-supported strategy is the right business model and has proven to be very valuable for advertisers so far.

Netflix, with its fee-only model, is in a sense caught between Scylla and Charybdis, having just increased its subscription fees by an average of 11% while struggling to hold on to its strong growth trajectory and being careful not to break the trend by driving away members who share their accounts with family and friends. During the conference call, it became clear that Netflix is now also turning to an ad-supported strategy, as CFO Neumann hinted at the company’s plans to boost revenue by adding ads to lower-cost memberships. This sudden change in strategy is certainly risky and leaves a stale taste that Netflix’s management is too sluggish with its monetization strategy.

Isn’t Comcast Losing Revenues Due To Cord-Cutting?

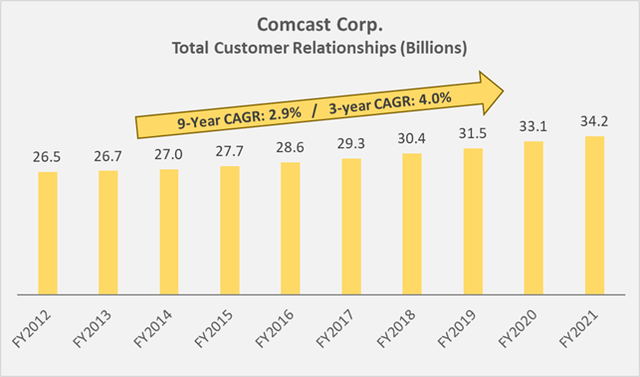

The cord-cutting phenomenon has been longstanding in the U.S., and Comcast has been no exception, with its video customer relationships declining steadily over the past decade and at an accelerating pace in recent years. However, and contrary to intuition, the company continues to report an ever-increasing number of overall customer relationships, as illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Comcast’s total customer relationships; note that the company did not report this statistic prior to fiscal 2012 (own work, based on the company’s 2012 to 2021 10-Ks)

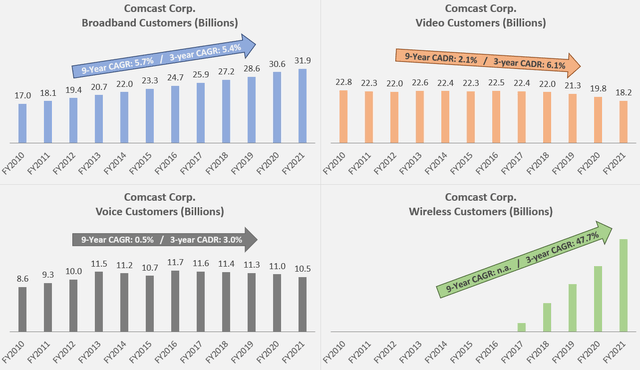

The long-term compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 2.9% can certainly be described as robust against the backdrop of the ubiquitous “cord-cutting” phenomenon. In Figure 2, I compiled the historical developments of broadband, video, voice and wireless customer relationships. While Comcast is obviously losing video customers at an accelerating pace, the company is remarkably successful in diverting those customers to broadband or wireless services, the latter growing at a very respectable CAGR of nearly 50% over the past three years.

Figure 2: Comcast’s broadband, video, voice and wireless customer relationships since 2010 (own work, based on the company’s 2010 to 2021 10-Ks)

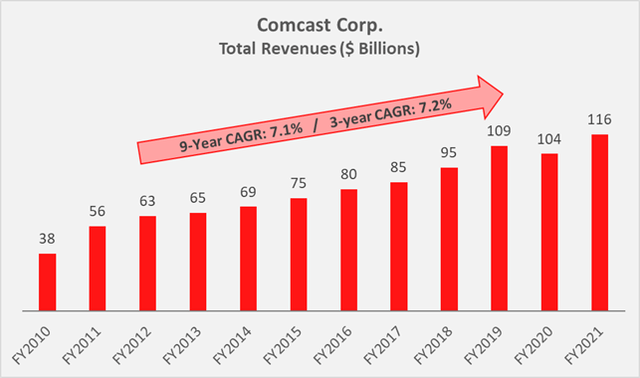

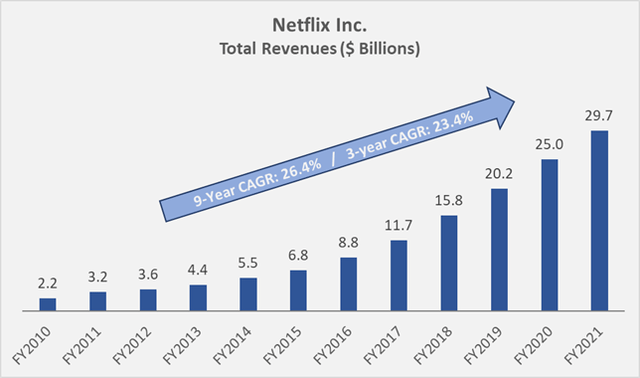

But not only is the number of Comcast’s customer relationships growing steadily, revenues are also on a good growth path (Figure 3). Of course, Comcast’s nine-year CAGR of 7.2% is dwarfed by Netflix’s 26.4% (Figure 4), but I would argue that we’re still seeing very respectable growth given the sheer size and nature of Comcast’s business. Also, Netflix is beginning to see signs of maturity as revenue growth has slowed in recent years and is only expected to grow 12% in fiscal 2022.

Figure 3: Comcast’s revenue history (own work, based on the company’s 2010 to 2021 10-Ks) Figure 4: Netflix’s revenue history (own work, based on the company’s 2010 to 2021 10-Ks)

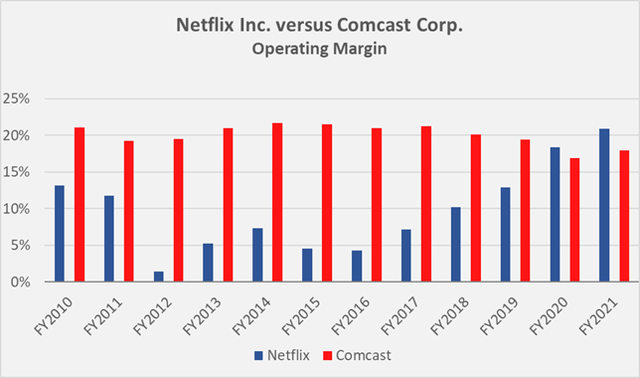

Netflix’s operating margin has risen sharply in recent years (Figure 5), supporting the hypothesis that the company is maturing. This is mostly attributed to the decreased requirement for marketing spend, which declined from 14% of revenues in 2010 to 9% in 2021. In comparison, Comcast’s advertising and promotion expenses are even lower, at 7% of revenues on average over the last decade. However, the company’s operating margin has suffered in recent years, due in part to the integration of Sky and, of course, the ongoing development of Peacock.

Figure 5: Netflix’s and Comcast’s operating margin (own work, based on each company’s 2010 to 2021 10-Ks)

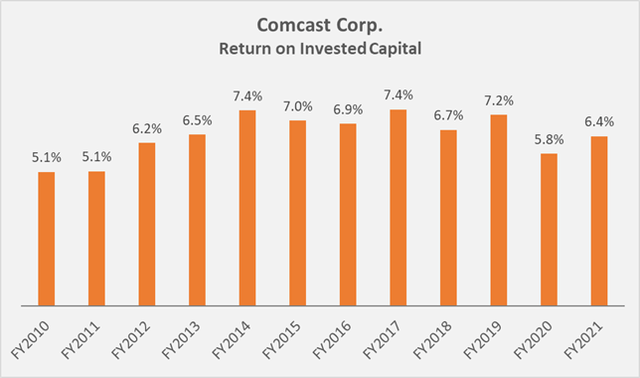

In terms of return on invested capital (ROIC), Comcast’s asset-laden balance sheet is certainly a burden and the company is at times only able to generate a return equal to its weighted average cost of capital (WACC) of currently around 6% (Figure 6). Netflix’s ROIC hovered around 6 to 7% a few years ago but steadily increased and came in at around 14% for fiscal 2021. Compared to Comcast, Netflix appears to generate stronger excess returns, but I deem a WACC of at least 10% appropriate for Netflix, taking into account its much riskier business and lack of diversification. Normally, I also analyze cash return on invested capital, as it is a much more transparent measure of a company’s profitability. However, since Netflix does not (yet) generate a stable free cashflow, this comparison seems meaningless.

Figure 6: Comcast’s historical return on invested capital (own work, based on the company’s 2010 to 2021 10-Ks)

Netflix’s Business May Be Risky – But Isn’t Comcast Even Riskier Because Of Its Debt Load?

The debt to equity ratios of CMCSA and NFLX are very similar at currently around 1.8, whereas CMCSA’s net debt is much higher at 2.8 versus 0.8 times EBITDA. However, it should not be forgotten that Comcast is a much more mature company with a very strong and reliable cash flow and that creditors are willing to lend to the company at a more favorable interest rate than Netflix. This is underlined by the difference of around 1.3 percentage points in the weighted average interest rate.

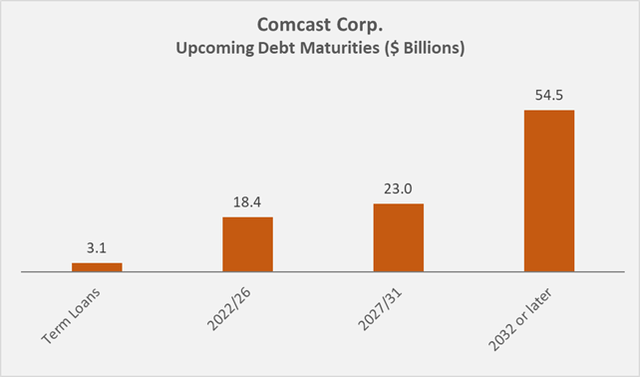

Unlike Netflix, which doesn’t have the luxury of piling up a large amount of cash every month, Comcast generated normalized free cash flow (nFCF) of about $16 billion in 2021. With it, the company is in the position to pay a dividend, repurchase its own shares and retire some of its considerable debt. At the end of fiscal 2021, the company reported net financial debt of around $86 billion, down from $108 billion three years ago. It would take Comcast between five and six years to retire all of its debt, were it to suspend its dividend and buybacks. This example is for illustrative purposes only and is not intended to suggest that the company should deleveraged completely. This is also underlined by the negatively skewed debt maturities, in that more than 50% of the company’s debt matures in 2032 or later (Figure 7).

Figure 7: Comcast’s upcoming maturities are negatively skewed in that more than 50% of the debt is due in 2032 or later (own work, based on the company’s 2021 10-K)

Also, Comcast’s interest coverage in relation to its normalized FCF is very stable at around 4 to 5 times normalized FCF. Nevertheless, I am pleased to see that the company is in the process of digesting the acquisition of Sky in 2018. In the long term, I would like to see a net debt to EBITDA ratio of around 2, so that the company has a significant surplus of borrowing capacity to deal with potentially upcoming imponderables.

Netflix is unlikely to be able to take on too much debt due to its still very unstable FCF, forcing it to dilute existing shareholders to fund, for example, executive compensation. The company’s fully diluted weighted average shares outstanding increased from split-adjusted 380 million in fiscal 2010 to 455 million in fiscal 2021. In stark contrast, Comcast reduced its shares outstanding from split-adjusted 5.64 billion to 4.65 billion in the same period, thereby boosting earnings per share and reducing the cashflow requirement for paying the dividend, which grew at a phenomenal CAGR of over 15% over the last decade. Note, however, that dividend growth has slowed in recent years to a nonetheless still respectable three-year CAGR of 9%.

Valuation

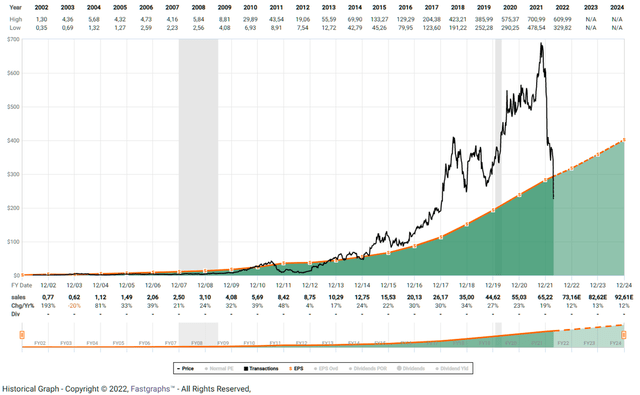

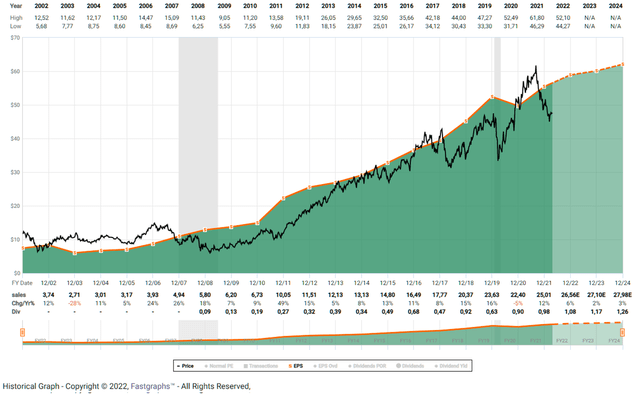

Netflix’s shares have lost nearly 70% since their peak in November 2021 and are currently trading for around $220. Shares of Comcast have also fallen significantly since the fall of 2021, down about 25% to $47 currently. Figure 8 and Figure 9 show the price-to-revenue graphs from FAST Graphs for Netflix and Comcast, respectively. NFLX is currently trading at 3.2 times revenue per share, below the normal price-to-sales ratio of 4.3 as determined by FAST Graphs. When NFLX peaked in late 2021, the shares changed hands at 10 times (!) revenue.

In stark contrast, CMCSA currently trades a multiple of 1.8, whereas the shares peaked at much more digestible 2.5 times revenue in late 2021. According to FAST Graphs, a price-to-revenue multiple of 2.2 is considered normal for CMCSA.

If you will, NFLX is currently trading at a slightly larger discount to its historical valuation than CMCSA (26% vs. 18%). I’ll leave it to you whether you deem this discount sufficient to compensate for the risk assumed as a shareholder of Netflix, given the company’s highly focused business model in an industry that I believe is increasingly commoditized and competitive. It should also be critically examined whether an average price-to-revenue ratio of 4.3 is appropriate for such a company. Personally, and my regular readers know this all too well, I am not interested in owning a business that is riddled with uncertainties, especially when those uncertainties are not even supported by solid and recurring cash income.

Figure 8: FAST Graphs chart for NFLX, based on revenue per share (obtained with permission from FAST Graphs) Figure 9: FAST Graphs chart for CMCSA, based on revenue per share (obtained with permission from FAST Graphs)

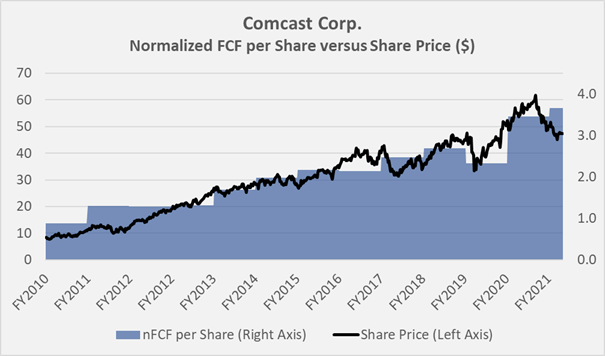

Due to the recurring and stable free cashflow, Comcast’s shares can also be valued from this perspective, i.e., by extrapolating nFCF into the future and then discounting it with an appropriate rate of expected return. A discounted cash flow analysis based on a conservative estimate of CMCSA’s normalized FCF of $13.5 billion, an expected cost of equity of 9%, and a terminal growth rate of 3% suggests that the shares are currently fairly valued. Note, however, that my assumption of a terminal growth rate of 3% may be somewhat conservative, given that Comcast has been able to grow its normalized FCF at a CAGR of 7% over the past decade. The overlay of Comcast’s nFCF per share and its stock price also suggests that the shares currently represent reasonable value, given the current normalized FCF yield of 7.7%, compared to the historical average of 6.8% (Figure 10).

Figure 10: Overlay of Comcast’s share price and normalized free cashflow (nFCF) per share (own work, based on the company’s 2010 to 2021 10-Ks, own estimates and the weekly closing share price of CMCSA)

Final Thoughts

Netflix is a sound business and most likely has a certain brand power. According to a recent study, Netflix is the first choice of streaming service if the more cost-conscious consumer had to choose a single service (i.e., 41% of respondents). However, the streaming industry is becoming increasingly competitive and Netflix could see itself participating in a race to the bottom in terms of profitability. That does not bode well for shareholder returns, and investors should ask themselves whether Netflix should still be valued as a growth stock. It should also be kept in mind that Netflix is up against financially more flexible competitors which may be able to outspend the company. This is nicely demonstrated in Comcast’s conference calls, where management continues to report significant EBITDA losses associated with its fast-growing streaming service Peacock in a less-than-emotional tone, as the losses simply do not matter to the business as a whole.

In stark contrast to Netflix, Comcast is a behemoth with a very well-diversified business that throws off significant amounts of cash each year that can be returned to shareholders and invested in new growth opportunities. In my opinion, Comcast is currently underappreciated by the market, in part due to the ongoing cable-cutting in the United States. Comcast’s shares also appear to be caught up in Netflix’s halo effect and the investors’ flight to safety, away from exuberantly valued tech stocks.

Finally, as a conservative investor, I would prefer Comcast over Netflix because the former pays a steadily increasing dividend that serves as a consolation during times of poor stock performance. In contrast, an investment in Netflix is “dead money” until the stock price recovers, which I personally still think is a risky bet given the fierce competition and the lack of a concrete plan for how the company will overcome the current challenges.

Thank you very much for taking the time to read my article. In case of any questions or comments, I’m very happy to read from you in the comments section below.

Be the first to comment