LeoPatrizi

JetBlue Airways (NASDAQ:JBLU) reported its second quarter 2022 financial results on Tuesday morning 2 August 2022. It was the last of the seven largest network-oriented U.S. airlines to report, leaving the ultra low cost carriers (SAVE, ULCC and ALGT) to report.

JBLU summary 2Q2022 financials (Jetblue.com)

JBLU’s results were not impressive with non-GAAP EPS of -$0.47 which missed by $0.36. Revenue was $2.45B (+63.3% Y/Y) which missed by $10M. JBLU became the second of the big 7 airlines to report a loss for the second quarter of 2022 and, along with Hawaiian Airlines (HA), JBLU is not expected to be profitable for the entirety of calendar year 2022. JBLU is hoping to return to profitability in the second half of 2022, largely as jet fuel prices continue their present decline and JBLU, like other airlines, works through its operational and labor inefficiencies. The common themes of airline earnings to date for the second quarter have been strengthening domestic demand, operational challenges in meeting that demand which has resulted in the need to reduce capacity, and cost control issues related to labor, fuel, and reduced capacity. JBLU suffered from each of those issues.

JBLU 2Q2022 operating stats (JetBlue.com)

Capacity and operational performance

JetBlue has long had trouble with operational reliability, bottoming out at 10th place out of 10 airline systems tracked by the U.S. Dept. of Transportation with an on-time percentage of 53.3% for the month of March 2022. JBLU recognized early on in the pandemic recovery that it did not have the staff to operate the schedule it had sold. To their credit, they were one of the first U.S. airlines to begin to reduce their schedules which resulted in capacity growth of a weak 2.3% for the second quarter of 2022 compared to 2019 after taking out approx. 10% of their summer flights. Other airlines, especially the big 3 global carriers with their more complex fleets and use of regional jets, operationally suffered well into the second quarter and into early July. Currently, all U.S. airlines are operating fairly near their historic levels of operational reliability – both in terms of on-time and cancellations using data that is publicly available. JBLU’s 2Q2022 results reflect its need to bring down its capacity. JBLU stock is down significantly after it reported, just as has been the case with every other U.S. airline that has reported their second quarter results.

US Airline On-time Performance (U.S. Dept. of Transportation )

Soaring costs

JBLU’s labor costs increased 20% which put pressure on its overall costs given its much lower percentage increase in capacity. Like other airlines, JBLU’s need to reduce capacity has pressured JBLU’s unit costs, just as has been the case with other airlines. Operational challenges, including the difficulty in getting the right employees in the right place has plagued airlines just as the FAA has struggled with getting its air traffic control facilities fully staffed, aggravating delays and resulting in higher employee costs. Like pilots, air traffic controllers take many months of training before assuming new roles and both labor groups faced significant turnover during the Covid pandemic.

JBLU’s concentrated position in the NE led to a marked increase in its fuel costs which nearly tripled for the second quarter of 2022 compared to 2019. On a per gallon basis, JBLU paid the most of any of the airlines that have reported so far at $4.24, due largely because of its large presence in the northeast where refinery capacity limitations have pushed up NE jet fuel crack spreads. JBLU has no hedges in place at present. The increase in unit fuel costs amounted to about half of JBLU’s overall increase in unit costs meaning that, absent hedging, JBLU has little control of a significant portion of its costs in a region which will likely see inflated fuel costs relative to other parts of the country.

JBLU return to profitability plan (JetBlue.com)

On a capex and balance sheet basis, JBLU continues to grow its fleet with the addition of new fuel efficient A321NEO and A220-300 aircraft. The A321NEO is used for JBLU’s transatlantic flights which are expected to increase as well as for its high-density domestic operations. The A220 is the most fuel-efficient small aircraft and JBLU expects to use the arrival of the A220s to accelerate retirement of its E190 aircraft which are some of the least fuel efficient on a per seat basis and also have some of the highest maintenance costs per seat in the JBLU fleet. JBLU notes that it will be retiring aircraft for the first time, indicating that its fleet spending is no longer just for growth; it is developing a plan to maximize use of its older aircraft and minimize end of life costs. Its fleet plan for now appears evolutionary and largely in line with how it has guided.

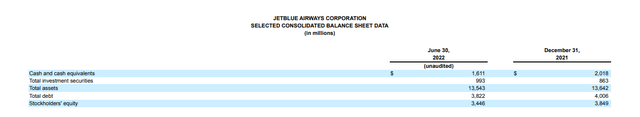

JBLU balance sheet items 2Q2022 (Jetblue.com)

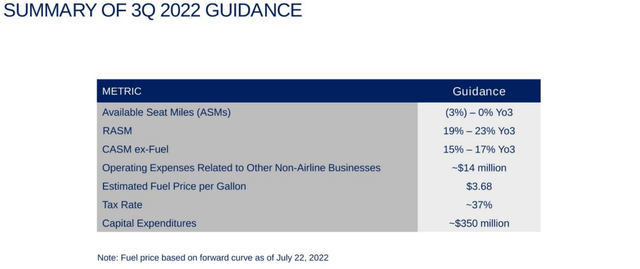

JBLU 3Q2022 guidance (JetBlue.com)

Strategic Uncertainty

JetBlue’s financial performance and outlook are reason enough for investors to steer clear but the company faces more challenges than any other airline. Their merger with/acquisition of Spirit has been more than adequately covered by business media but understanding what brought JBLU to the merger is worth considering. Add in the Dept. of Justice’ challenge of the U.S. DOJ’s challenge to the American (AAL)/JBLU arrangement and JBLU investors have lots to be concerned about. Investors need to understand each of those challenges.

JetBlue was created over 20 years ago as an airline that would bring low prices to the NYC area which had long not had much low fare service, in large part because of the slot controls that have been present at the big 3 NYC airports – LaGuardia (LGA) and JFK (JFK) International airports in Queens and Newark International in New Jersey. For most of the jet age, JFK and LGA have been the primary airports for NYC travel until Continental Airlines (which later merged with United) developed the NJ airport into a major hub; Newark is now the largest hub in the Northeast U.S. for United and the highest local market revenue in the U.S. American’s original headquarters were at LGA and it has had a major presence at LGA and JFK airports for its entire existence. However, Delta (DAL) became the largest airline at both NY airports as a result of slot acquisitions and organic growth during the rare times when the FAA eliminated slot controls at those two airports. Newark was slot controlled for much of the time since JBLU existed, meaning that there have always been significant barriers to entry for low cost airlines in NYC. In order to start service and with low amounts of low cost service in the NYC area, JetBlue was gifted dozens of slots at JFK airport which allowed it to begin service and it quickly became a low fare challenger to the dominant legacy/global airlines that have dominated NYC air transportation, a role which JBLU has embraced and used to shape its identity.

JetBlue’s growth quickly made it difficult for American to retain its level of service from JFK initially to the Caribbean where American was long the dominant carrier. Over the past 20 years, American has shrunk its presence at JFK while Delta has used AAL’s reduced interest in the market as an opportunity to grow. In Boston, Delta began building a large, new terminal before 9/11 and JetBlue used its much stronger finances as a young airline post 9/11 to fill the terminal space where Delta previously operated and JBLU quickly became the largest airline in Boston as DAL and USAirways (predecessor to AAL) focused on survival and their hubs in other parts of the country. Because JBLU established itself as a leisure-focused airline, the third major pillar of its network has been Florida with its largest presence in Ft. Lauderdale where it has attempted to create a hub reaching into the Caribbean and mirroring what American has built with its hub in Miami, the largest and most dominated U.S. airline hub to/from Latin America. Ft. Lauderdale has been a highly competitive airport due in part to Miami airport’s airline pricing system which made the airport unattractive to low fare carriers.

The problem with JBLU’s business plan is that it has built its entire network around highly competitive markets while nearly every other airline not just in the U.S., but throughout the world has markets which it dominates, leading to stronger pricing and a more loyal or captive passenger base. While American has its massive hub at DFW airport which leads to its dominance in the south central part of the U.S., and Delta dominates the Atlanta and east coast as well as other hubs in the U.S., and even Southwest dominates its hubs at Chicago Midway, Dallas Love Field, and Houston Hobby airports, JetBlue has never found markets which it can dominate. Indeed, as the youngest existing large jet carrier, many of the most valuable markets throughout the U.S. have long service histories with the legacy carriers and Southwest – which, while not a legacy, is more than twice as old as JBLU. Delta is now the largest airline at JFK airport, JBLU’s largest base and DAL has also aggressively regrown at Boston while JetBlue has fought it out with other low cost and ultra low cost carriers for a large position in Florida including competing large positions by Southwest and Spirit at Ft. Lauderdale. The strategic reality JBLU has found itself in resulted in the two major strategic initiatives that JBLU has engaged in and which now both face significant government oversight and a need for approval.

The Northeast Alliance with American

American and JBLU had a previous codeshare relationship but both recognized the benefits from starting a new relationship. The biggest motivator for what became the Northeast Alliance (NEA) was that American risked losing slots, particularly at JFK airport, because of underutilization. As the smallest of the big 3 global airlines in NYC, AAL has struggled to compete in NYC against much larger Delta networks in NY state and United’s network in New Jersey. In addition, AAL is the third largest airline at JFK – with fewer U.S. airlines at JFK than at either LaGuardia or Newark airports. American envisaged an arrangement with JBLU as offering codeshare opportunities that would connect JBLU’s domestic markets with AAL’s long-haul network. Based on statements from both airlines and limited data, this aspect of the NEA has been successful. AAL and JBLU are also cooperating on several other passenger amenity aspects including shared loyalty program coordination, joint AAL lounge access, and integrated seat assignments.

The NEA was approved by the U.S. Dept. of Transportation under its antitrust authority but includes several other aspects including schedule coordination from NYC and Boston airports and the ability of American and JetBlue to swap slots with each other at LGA and JFK airports. The DOJ, which has authority over mergers and large asset acquisitions has objected to the NEA based on these features of the arrangement which the DOJ notes are only allowed domestically in the case of a merger. While the lawsuit against NEA is, in some respects, the product of overlapping authority between the DOJ and DOT and the DOT’s approval of an arrangement which the DOJ believes it has authority to approve, the future of the NEA as it currently exists is in doubt as the case goes to trial in a Boston court in September. Even before its Spirit merger/acquisition, the NEA gave the combined AAL and JBLU the dominant position in terms of number of flights and seats in the NYC and Boston areas. The DOJ was joined in its lawsuit by a half dozen states, all of which see the collaboration of AAL and JBLU as problematic in limiting capacity, resulting in higher industry fares between their states and the Northeast as a result of the NEA. It is worth noting that American has a codeshare and alliance relationship with Alaska Airlines (ALK) which does not involve some of the features of the NEA and is not being challenged by the DOJ. While it is hard to know how the DOJ will position the NEA case at trial, the overlap between the Northeast and major leisure destinations make it very likely that some parts of the NEA, potentially including the slot swap features, will be scaled back. It is impossible for those outside of either American or JetBlue to know the financial benefits of the at-risk parts of the NEA, or all of it, but that benefit is likely to be lower than AAL and JBLU have planned and possibly achieved so far.

The DOJ’s case against the NEA is enhanced by JBLU’s deal to buy Spirit Airlines, which has been covered and discussed well on Seeking Alpha. JBLU initially launched a hostile all-cash bid for SAVE after SAVE and Frontier Airlines (ULCC) agreed to a friendly merger. Pursuit of SAVE by JBLU indicates that the NEA alone does not solve all of the strategic challenges which JBLU faces. While JBLU was intended to be a premium amenity, low cost airline in high volume markets, SAVE operates a very different business model as an ultra low cost carrier, airlines that have very low fares for basic transportation which are augmented by a menu of additional services. Ultra low cost carriers fit more seats into each aircraft, meaning that there are lower costs per unit of production. In addition, SAVE’s network is largely not built for connecting traffic so that each flight stands largely on its own from a customer’s perspective. JBLU has said that it intends to transition SAVE from an ultra low cost carrier to JBLU’s model.

No other large airline merger since deregulation has involved the acquisition in entirety of a carrier with a “lower” business model; legacy carriers have largely merged with or acquired other legacy carriers or their assets while low cost carriers have merged with other legacy carriers. The DOJ will be faced with several significant issues to consider in approving JBLU’s acquisition of SAVE including the increase in fares which will happen as an ultra low cost carrier is transitioned to a higher fare and cost base. In addition, conversion of SAVE aircraft will result in a reduction of the number of seats on those aircraft since JBLU touts more space and amenities than other airlines. While analysts and JBLU expectations are for approval in 12-18 months, the number of issues involved that have not been part of other airline mergers will require a level of scrutiny the industry has not seen. Because JBLU’s acquisition involves a cash dividend to SAVE stockholders on their approval of the transaction and a ticking fee until the transaction closes with DOJ approval, JBLU will be spending hundreds of millions of dollars at a much sooner point in time than in other airline mergers. Once approved, aircraft conversion will also very likely be more expensive per unit than in other mergers.

While JetBlue has bold plans to remake itself, there are far more strategic risks – much of it associated with the DOJ and the number of consumer and government voices that want to be heard – than has been the case for any other merger. While JBLU is starting the process with a stronger balance sheet than most legacy carriers had when they entered into mergers, JBLU is currently losing money while those larger legacy and older low cost carriers airlines are not. JBLU’s rationale for the merger is to be better positioned to compete with the big 4 but it also will have to compete against them as much more profitable and strategically stable enterprises during the period when JBLU’s NEA and merger will be scrutinized.

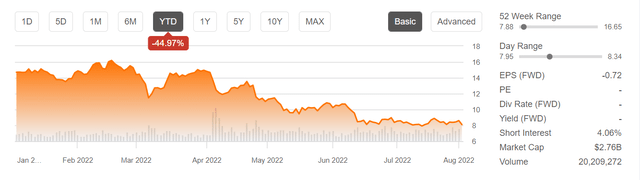

JBLU YTD stock performance (Seeking Alpha)

One of the Industry’s Worst Stock Performances

JBLU has registered one of the worst performances on the stock market of any airline and that is not likely to change. ULCC stock has seen its stock surge once the merger with SAVE was pulled off the table; airline mergers are always messy. ULCC not only avoids the risk of being dragged down in a merger, becoming the largest ultra low cost carrier left in the U.S. Many believe that Frontier will be a shoe-in when it comes to assets that have to be divested by JBLU/SAVE but the DOJ and DOT both are certain to recognize that government efforts to pick winners in the marketplace have not resulted in the best competitive outcome. It is also likely that divestitures will not fix an increasingly concentrated marketplace because there are so few remaining lower fare carriers “below” JBLU which is wanting to create a niche for itself after the airline industry has already heavily concentrated. At the “upper end” of the airline industry, legacy/global and more established low fare carriers have been better able to pass along higher costs such as for fuel and labor than JBLU or ultra low cost carriers; for the first time since deregulation of the U.S. domestic industry nearly 45 years ago, legacy carriers are competitively stronger than they have ever been vis a vis the rest of the industry including relative to JBLU. As a result, JBLU stock is not going to be attractive for many years, especially in an industry which is not terribly attractive for long-term investors. While there aren’t indications that JBLU stock should fall significantly further, there is little reason to expect appreciation. JBLU investors should probably lick their wounds and walk away.

Be the first to comment