SARINYAPINNGAM/iStock via Getty Images

We’re witnessing the unedifying spectacle of a new UK government shooting itself in the foot when it unleashed a “mini” budget on unsuspecting markets. It was full of unfunded tax cuts (45B pounds, which, as it happens, were mostly cancellations of promised tax increases) on top of a blanket energy price cap that could cost tens of billions.

These measures awoke a dormant phantom, the bond vigilantes, which in a way is surprising as the UK is actually one of the more fiscally sound countries in Europe, or, better put, one of the least bad. We see multiple reasons for this unexpected turn of events:

- Bad communication, the radical plans came as a bit of a surprise.

- Markets doubting the competence of the new government, which dispensed with the usual forecasting from the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) and sacked the highly experienced permanent secretary to the Treasury Tom Scholar in an effort to bypass the Treasury “orthodoxy.” As one observer noted; “You may believe in markets but that does not mean that markets believe in you.” Even the IMF weighed in

- Hugely expansionary fiscal policy is working at odds with the Bank of England’s (“BoE”) efforts to contain inflation.

- Not widely appreciated (or even known), UK pension funds, large investors in UK gilts, were making widespread use of derivatives in what is known as LDI or Liability Driven Investments.

These LDIs are a serious problem:

investment managers then hedge the risks further through derivatives, often using existing bond assets as collateral against the contracts. Anyone with a private pension may be shocked to learn that the amount of liabilities held by UK pension funds hedged using LDI strategies has roughly tripled in size to £1.5 trillion between 2010 and 2020, the equivalent of roughly 40pc of the UK institutional asset management industry. What is more surprising is that the £1 trillion tied up in Government bonds proved to be the weak link in the chain.

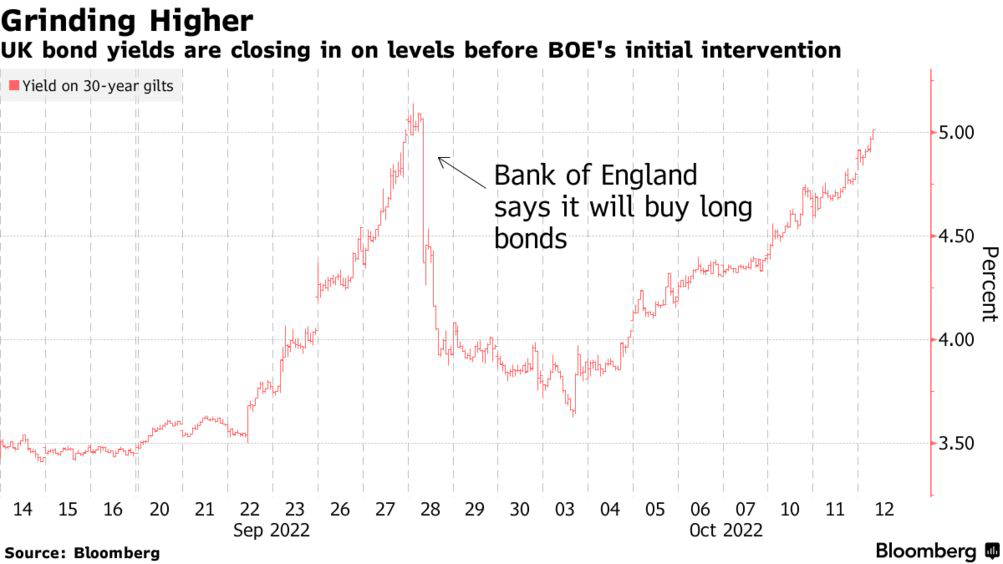

With market confidence in gilts tanking as a result of the mini-budget, yields spiked and threatened a vicious cycle in which pension funds could be forced to liquidate gilt positions, creating a snowball effect. This was clearly happening and forced the BoE to intervene via a £65B bond-buying program.

That intervention was a forced U-turn, as the BoE was actually embarking on QT to which they were quite committed, at least as late as last August:

Last week the BoE said it would have a “high bar” for halting its QT bond sales in the event of economic or financial market turmoil.

However, one can clearly appreciate that they had an emergency at hand, which wasn’t confined to the bond markets but to a lesser extent also in sterling with the pound sinking almost to parity with the dollar at the height of the crisis:

The BoEs program is ending on Friday, October 14, and its governor has given little sign he’s willing to extend it, which is perhaps the main reason why gilts have moved sharply down again, with the yield now back at the 5% levels. This forced the BoE to start the intervention:

Bloomberg

Even the IMF weighed in, and BoE intervention looks like it was only a temporary stop-gap (our emphasis):

On a day when fresh action by the UK central bank failed to halt the upward move in government borrowing costs, the Washington-based IMF said a shift in policy from Truss and her chancellor would “change the trajectory” of interest rates. The IMF said the Bank and the Treasury were “like two people trying to steer a car in different directions” as it highlighted the turbulence in markets caused by the chancellor’s 23 September package.

All this looks like a bit of a predicament to us:

- The UK government can’t really make more fiscal U-turns than it already has without losing its remaining credibility and the core tenets of its guiding philosophy, even if part of her party is demanding exactly that.

- There is also not much room for plugging the £60B hole in its public finances through spending cuts, like raising benefits with wages (6%) instead of inflation (10%), which the PM actually ruled out again.

- Mortgage rates are rising fast (and during the crisis almost half the mortgage products were actually withdrawn from the market). With UK mortgages especially vulnerable to short-term interest rate swings this looks like a big drag on the economy, potentially nullifying any positive growth impulse from the mini-budget.

- With the bond vigilantes at the door, the BoE emergency program likely ending and interest rates going up, the room for increased borrowing seems to narrow by the day.

- Will the BoE be forced into a U-turn? It’s disconcerting that the BoE intervention hasn’t been able to stem the rise in yields.

So they can’t raise taxes, they can’t cut spending and they can’t borrow more, something will have to give. Longer-term, there is more likelihood for the situation to ease:

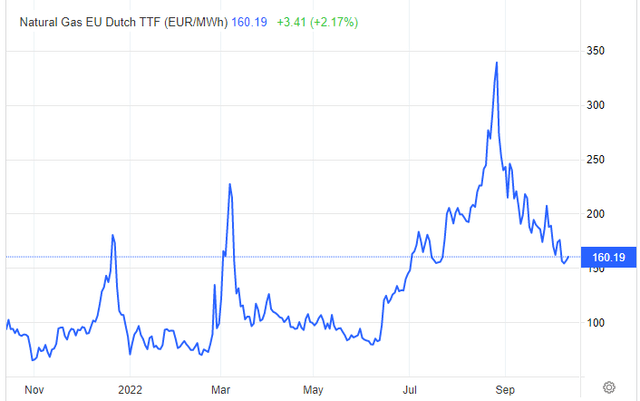

- Wholesale natural gas prices have come down fairly sharply in the EU recently, this could greatly decrease the cost of the blanked price cap in the UK, or even eliminate the cost altogether, providing some much-needed relief on borrowing requirements.

- The timing of the fiscal expansion could be fortuitous, as we expect inflation and interest rates to top fairly soon, with economic growth becoming the main concern soon after.

So our guess is that the UK government will try to sit it out (and they don’t seem to have many policy options anyway), but it remains to be seen whether the markets (or Putin and the gas prices) will cooperate.

We think the markets are likely to force the issue, and much of the tax cuts will be postponed. There are some early indications of that, with the planned corporate tax cut and dividend tax cut likely victims.

Another idea we’ve seen is to gut Whitehall bureaucracy, instead of front-line personnel, but that, too, is anybody’s guess at the moment.

More worryingly is the observation that if the UK can fall foul to the bond vigilantes, there are more obvious candidates in worse fiscal shape (a host of emerging economies, and then, there is the eurozone periphery, most notably Greece and Italy).

So far, real interest rates are still quite negative, which is actually a boon to the sustainability of public finances.

Then there is the return of large derivatives positions producing financial instability and forced central bank interventions. We wonder if the UK is the canary in the coalmine if a mere 150bp rise in gilts can produce such mayhem on the financial markets and force the central bank to intervene.

Conclusion

If even a rich and (relatively) fiscally sound country like the UK can get clobbered by the financial markets in the blink of an eye, with derivatives playing a destabilizing goal, this should concentrate minds.

If the monetary tightening cycle has much further to go, it will reveal other weak spots and we can expect more of these types of crisis.

The first place to look is in emerging markets, where dollar-based loans have been popular. These are now twisting and turning in the wind under the triple whammy of a slowing world economy, rapidly rising interest rate and the surge in the U.S. dollar.

Inflationary pressures are already receding and moderate inflation isn’t actually all that bad in this environment, as it gently reduces sky-high debt levels out there. However, we don’t think the Fed, hell-bent on restoring its lost credibility, is sensitive to these kinds of deliberations, at least not yet.

Be the first to comment