patpitchaya/iStock via Getty Images

A confusing time

Back in March and April 2020, when the entire world was engulfed in an end-of-the-world sentiment due to the Covid-19 pandemic, when WTI benchmark for a time reached -$30 thanks to an oil price war, it only took the common sense that motorists would prefer ICE-powered wheels than horse-drawn buggies to move around, if just for a few more years, to compel me to back up the truck with energy stocks that were being given away.

Today, the signals from the market seem to be not so clear-cut. On the one hand, oil and gas companies are printing money and using that cash flow to reward shareholders. Politicians in the developed world have halted pipelines, suspended leasing, released from the Strategic Petroleum Reserve what was meant to serve only as insurance against future interruptions in foreign supplies, and done everything a Luddite would to sabotage the energy industry to secure votes of the woke carbon-neutralists; today, they implore domestic producers as well as foreign state terrorists/dictators to turn on the tap and flow more oil so as to appease motorists and reduce Russian oil revenue. Our journalists who took on the task of indoctrinating young trusting minds with absolute urgency of expedited decarbonization (even though technology and infrastructure are not yet ready for a clean break from fossil fuels), now find time to report angry people in developing countries, such as Sri Lanka, Pakistan, and Ecuador, protest or even riot to demand sufficient supply and lower prices of fuels.

On the other hand, the world’s major economies are either already in or being pushed into a recession that some economists say could be worse than 1929. The Fed is raising interest rates to combat rampant inflation not seen in four decades. Few – including Jerome Powell himself – seem to believe in the promise of a soft landing of the world’s largest economy. Meanwhile, the world’s second economy is collapsing in slow motion thanks to self-inflicted rolling lockdowns, a picture not so rosy to sophisticated observers as the state-released economic data seems to suggest. Soaring energy prices, before and after the Russian invasion of Ukraine, have brought Europe to her knees. A Japanese recession would not even be news-worthy these days. It is natural for investors to ask: a recession is supposed to result in a crash in oil and gas prices, is it not?

It is such a confusing time.

Below, let’s take a look at the structural forces that drive the oil business cycle to see whether now is a good time to buy oil and natural gas stocks, as represented by SPDR S&P Oil & Gas Exploration & Production ETF (NYSEARCA:XOP).

Where oil is in the business cycle?

High oil prices have brought back the oil peak specter. If one chooses to be informed by some of the more extreme pundits, he would be led to believe oil is heading for $12, where it last was in the 1970s. However, the oil peak theorists may have failed to understand the way the oil business cycle works.

Discerning industry observers have known for a long time that oil industry business cycles are controlled by structural factors that operate both on the demand side and the supply side in a global geopolitical and macroeconomic context, as Stephen Martin explained in his contribution in the book ‘The Structure of American Industry‘.

Demand

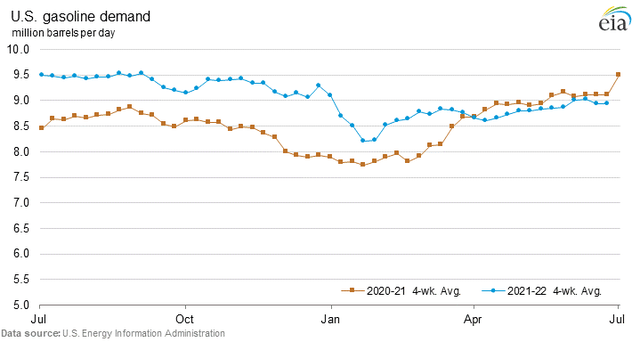

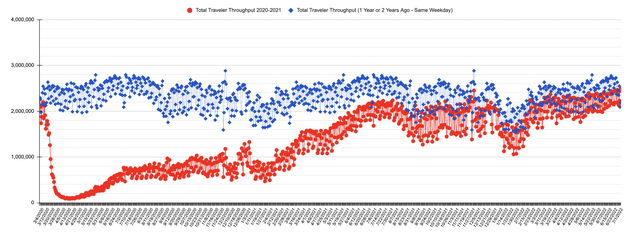

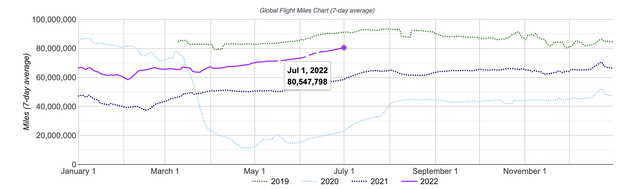

Global demand for oil is still in the process of recovery from the Covid-19 crash, as can be seen in U.S. gasoline demand, U.S. air travel, and global flight miles (Figs. 1, 2, 3).

Fig. 1. U.S. gasoline demand (Energy Information Administration) Fig. 2. U.S. passengers through TSA checkpoints (Laurentian Research based on TSA data) Fig. 3. Global flight miles (Airportia)

Going forward, the momentum of demand growth in developing economies will likely be stronger than in the U.S. and Europe:

- Take Mexico, Grupo Aeroportuario del Sureste (ASR) reported passengers in May 2022 were up 20.4% from that in pre-Covid May 2019, while Grupo Aeroportuario del Pacifico (PAC) announced air travelers through its 14 airports rose 15.3% compared to 2019.

- For another example, the economy of Thailand recovered strongly as private consumption expanded by 11.3% in May. The Thai government lifted on July 1 Covid-19 related measures (including Covid-19 test on arrival and quarantine) for vaccinated international travelers, which should further drive the tourist economy.

- Although China may not be fully reopened until the 20th CCP national congress scheduled for the 4Q2022, Shenzhen and Shanghai, two main manufacturing hubs on the East Coast of the country, had undergone strict lockdowns and are reopened.

Taking one step back, oil demand can be divided into an inelastic element and an elastic element. To that end, we have a perfect data point to pin down the inelasticity of oil demand: In 2020 when the entire world was locked down, when the global economy came to a standstill, oil demand destruction was ~20%, according to Amrita Sen at Energy Aspects. That suggests some 80% of oil demand is inelastic and any impact of a future recession will be on the remaining ~20%.

- However, it is highly unlikely a Fed-induced recession will cause an impact anywhere near the 2020 Covid lockdowns in terms of severity. The resultant demand destruction will most probably be a fraction of the ~20% as in 2020.

- Furthermore, as discussed above, the expansion or contraction of various economies in the world are not expected be so synchronized as during the Covid shock. Should a recession occur in the U.S. and Europe, its negative impact on oil demand may well be offset in part or fully by the strong recovery in developing economies. Consequently, demand growth at a much reduced rate cannot be ruled out in the event of a recession.

We should also not forget there is a secular movement of populism boiling in the backdrop of this oil cycle. The pain of rising fuel costs will indeed be acutely felt by the poor; the livelihood of the most unfortunate may be threatened, while some may have to, e.g., forgo a trip to visit grandkids so as to pay medical bills. However, with the world in roaring populism, total income of the working class – the 99% – is expected to grow due to rising wages and various government redistribution programs, which is expected to blunt the impact of rising fuel costs.

- The White House asked Congress to suspend federal gas taxes for three months, to shave 18.4 cents per gallon off the price of gasoline and 24.4 cents per gallon off that of diesel, and encouraged states to halt their state and local gas taxes on gasoline (ranging from 8.95 cents to 57.6 cents per gallon) and diesel (ranging from 8.95 cents to 74.1 cents per gallon).

- Europe announced one-time inflation relief payments, ranging from ~€260 to €800. In the U.S., California will send out inflation relief checks of up to $1,050 to ~23 million residents.

- The Ecuadorean government agreed with indigenous leaders to reduce gasoline prices by 15 cents per gallon (from $2.55 to $2.40 for gasoline and from $1.90 to $1.75 for diesel), following more than two weeks of protests that had paralyzed the country.

These income redistribution programs will help delay demand destruction. The rich, despite their private jets and car fleets, will not burn less fuel just because the prices are high. The Obamas just installed a 2,500-gallon propane tank at their Martha’s Vineyard mansion.

Supply

As compared with the murky demand outlook, the oil supply situation is actually less uncertain. That’s because there is a causal linkage between past investment and current production. It typically takes ~7 years on average to discover, delineate and develop an oil project. The seed of today’s tight supply was planted ~7 years ago.

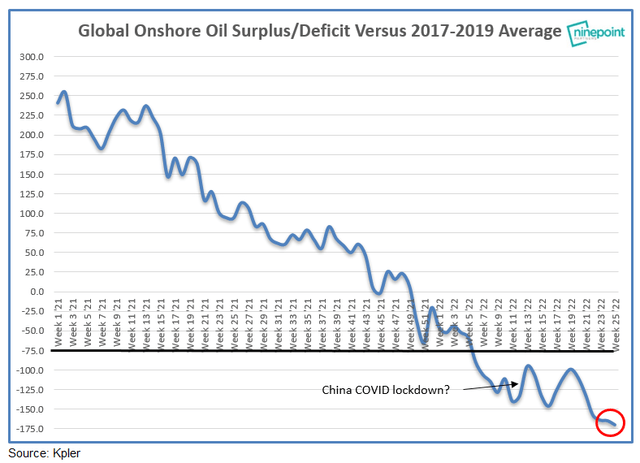

There is little spare production capacity anywhere in the world today for producers to raise supply. As a result, global oil inventories continue to draw down (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4. Global onshore oil surplus/deficit versus the 2017-2019 average (Eric Nuttall at Ninepoint)

- OPEC, producer of ~30% of the world’s oil, has over-complied relative to its agreed quota. Even as the oil prices are soaring, they have not been able to produce as much as they are allowed to. There are two primary reasons behind its production weakness: firstly, even the best-endowed Mideast producers have tight spare capacity these days; secondly, Libyan production fluctuates between zero and 1.2 MMbo/d due to internal strife and Venezuelan production has continued to fall.

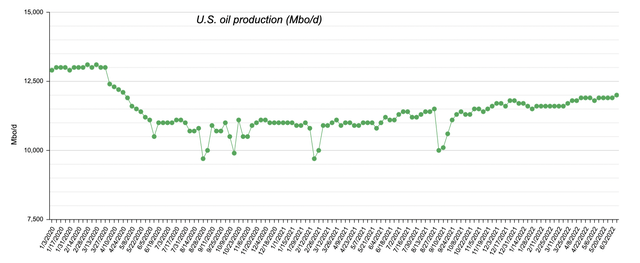

- U.S. production hovers around 11.5-12.0 MMbo/d, still below the former peak in pre-Covid time (Fig. 5). In previous bull cycles, producers increased capital spending to capture high commodity prices. In this cycle, U.S. companies are slow to ramp up capital spending, which is understandable given the industry has been told by Wall Street that it should focus on rewarding shareholders, by the public that it is dirty and unwanted, and by the government that it is in terminal decline and being ‘phased out’. According to the most recent Dallas Fed survey, even if an operator wants to drill and complete an extra well beyond its capital budget, it takes more than six months to get it done, thanks to supply chain constraints and a shortage of skilled labor.

Fig. 5. U.S. oil production (Laurentian Research based on data from EIA)

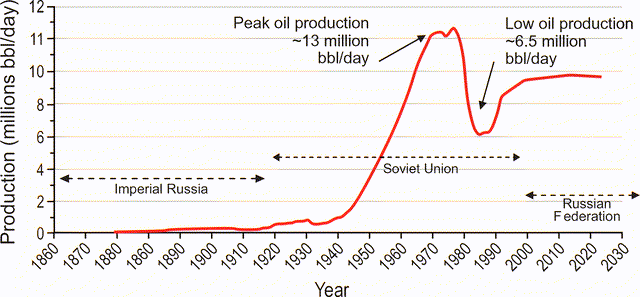

- Since the start of the Ukraine war, the West has sought to purge Russian oil and gas from the western supply chain. Although some countries struggle to wean themselves off Russian oil and gas, the Rubicon has been crossed. Meanwhile, China and India emerge as primary buyers of Russian oil, thus creating a segregated global oil market. I believe Russian production will most probably suffer from long-term decline going forward, for the following reasons: firstly, Putin’s decision to nationalize the Sakhalin-2 gas and oil project will effectively kill any hope of FID upon the end of the war; secondly, partial or full pullout of western oilfield service firms from Russia will leave a void that cannot be filled, which will have a detrimental impact on the country’s production capacity in the medium to long term. Recall that, following the collapse of Soviet oil production from 13 MMbo/d to 6 MMbo/d, it took western OFS firms more than 10 years to help raise the output to 10 MMbo/d (Fig. 6). Likewise, should Russian production decline unnaturally this time, it would take a decade if not longer to restore it. In the long run, no country will be able to replace the lost Russian production, perhaps with the exception of Venezuela – another source of uncertainty.

Fig. 6. Russian oil production (Frances J. Hein)

Business cycle

An oil bull market has its own internal dynamic that operates relatively independently of the general market. During the 14-year duration of the last oil bull market, there were two major recessions, namely, the dot.com bubble burst and the GFC. Both recessions resulted in a flash crash in the oil price. However, the oil market managed to go on after the interruption because the inner logic of the business cycle remained intact (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7. WTI price chart (Laurentian Research)

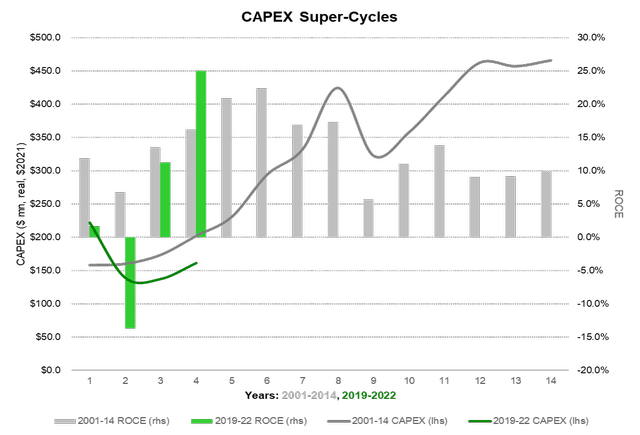

Eventually, only over-investment can kill an oil bull market. The 2010s oil bull market came loose after years of aggressive investments in capacity construction, especially by the U.S. shale producers.

That said, capital spending so far in this cycle is extremely low as compared with that during the peak of the previous cycle, implying the current oil bull market is likely still young (Fig. 8). Structurally speaking, indications are that we are probably still in the early innings of an up-cycle, as eloquently stated by Arjun Murti:

I disagree that we are closer to a long-term peak than a trough, however, when (1) reinvestment rates and capital spending are near trough levels, (2) there is limited spare capacity anywhere in the world, (3) a Top 3 oil and gas producer (Russia) is turning into a pariah state, and (4) current western world politicians and policy makers remain stuck in apocalyptic, Malthusian “climate only” ideology.

Fig. 8. CapEx super-cycles (Arjun Murti)

Murti sees the danger of calling a top prematurely:

In the 2000s super-cycle, when oil first traded above $30/bbl after a period between $15-$22/bbl (nominal) in the 1990s, just about everyone prematurely called peak; history appears to be repeating, or at least rhyming.

It is my working hypothesis that where we are today in the ongoing oil bull market (point A’ in Fig. 7) is structurally analogous to ca. 2001 in the previous cycle (point A in Fig. 7).

Investor takeaways

It is indeed a confusing time for investors who are weighing the risk of going long oil and gas stocks. A recession may lead to oil stocks going down with the general market. China is yet to exit from rolling lockdowns. The Ukraine war adds geopolitical uncertainty. However, just as Warren Buffett said,

“The future is never clear; you pay a very high price in the stock market for a cheery consensus. Uncertainty actually is the friend of the buyer of long-term values.”

In contrast to macro-economic signals, we do know that a host of oil and gas stocks are printing money at $100 WTI (the vast majority of which will still make good money at $75 or even $55 WTI), that management is deploying that rich free cash flow to reward shareholders, and that these stocks still represent great value. So, it is a great time to pick your favorite stocks from the oil patch.

Warren Buffett is taking advantage of the recent selloff to back up the truck with Occidental Petroleum (OXY) stock, buying from skittish sellers. With Buffett long oil stocks, are you buying your favorite oil and gas stocks?

Be the first to comment