Khanchit Khirisutchalual

It seems widely accepted that higher inflation is a problem for the market and that the longer this problem lasts, the harder it is for investors to ignore it. As a result, longer-lasting inflation is seen as a catalyst for stocks to go lower.

I’ll argue that this is hardly the case over the long term.

Yes, High Inflation Can And Should Immediately Lead To Lower Prices

First of all, let’s say that there’s a lot of truth to the expectation that in the short-term, high inflation can destroy stock prices.

This is the result of at least 2 things:

1) Higher Inflation Is Followed By Higher Interest rates

Higher interest rates are driven both by central banks trying to contain inflation by raising short-term benchmark rates and because bonds become increasingly unattractive to investors, due to declining real rates of return (deeply negative, in fact).

Bond selling (or lack of buying), in turn, creates lower bond prices. Lower bond prices for similar coupons lead to higher interest rates.

For equities, higher interest rates have two major consequences:

- First, bonds become more of an alternative to equities, since they now have higher yields. Indeed, for years TINA (There Is No Alternative) was even one of the theses put forth to explain why no valuation was too high, to buy stocks. As interest rates go higher, an alternative emerges.

- Second, Equities see valuation pressure. Interest rates are key to discount future cash flows. If interest rates are higher, then future cash flows are worth less. Market multiples thus contract in the presence of higher interest rates. Lower market multiples for the same (or lower) profits lead to lower stock prices.

2) Timing And Sector Mismatches

Another problem from high inflation is that:

- Sectors don’t all feel it the same way. Some sectors can pass on inflation to their customers. Others can’t. Some sectors are in foreign markets (like commodity producers), while sectors reliant on commodity inputs can be inshore.

- Inflation can also be felt quicker than it can be passed on. Price increases for consumers can take time to be absorbed while the consumer adjusts his purchasing patterns. Input costs can rise quicker, and lead to margin pressures.

Seen from these two angles, we can argue that high inflation does immediately produce a significant headwind for the market. Especially, of course, if the market is very expensive going into such a high inflation episode – as the US market certainly was.

So Why Do I Say Inflation Doesn’t Necessarily Lead To Lower Stock Prices?

I say it because the opposite – higher stock prices – might actually be the most common outcome from very high, sustained, inflation.

Why? Because revenues, profits and stock prices are “nominal realities”.

What does that mean? It means that as time goes by, as markets stabilize at SOME valuation multiple, and margins also stabilize at some level, then as inflation runs through the profit and loss statements of all companies aggregated together, the resulting profits go higher and higher in nominal terms. Since the valuation multiples can’t collapse forever, at some point the market is necessarily pushed higher by inflation.

This is what’s commonly observed in hyperinflationary situations, where equity markets typically explode higher. They nearly immediately explode higher, because the mechanism inflating revenues and profits, if prices are shooting up very quickly, very quickly overwhelms margin and valuation multiple compression.

The same that happens with hyperinflation, happens with just high inflation. It’s just a slower, but similar end result. Indeed, a large part of the stock market’s huge run over the last century is simply the inflationary mechanism working over a long timeframe. High inflation just compresses this effect.

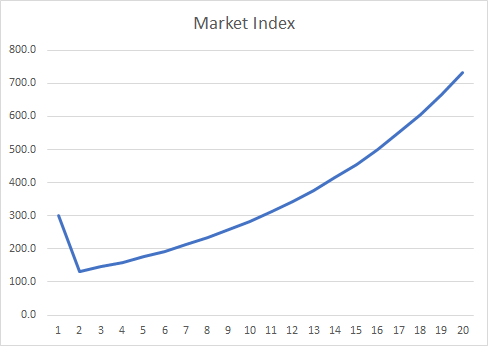

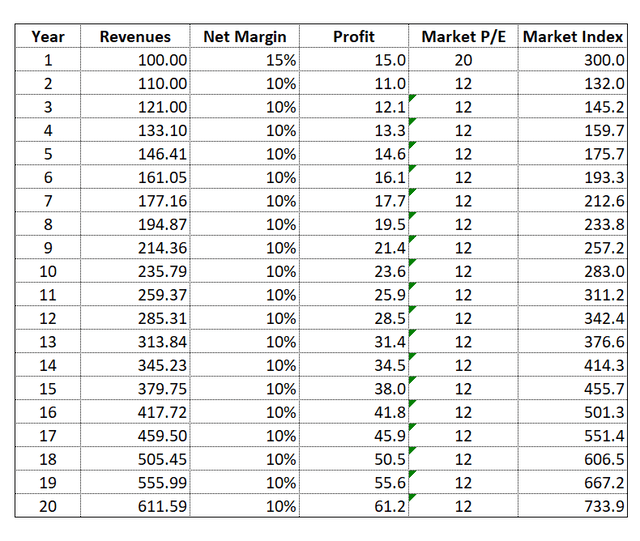

We can illustrate this effect with 10% inflation over several years and allowing for an initial contraction on margins and market multiples. We can even ignore economic growth and just assume companies in general are selling flat volumes of ever-more-expensive products/services. Notice that NO recovery is assumed for either profit margins or valuation multiples. Here’s what happens:

Own research

Notice also that negative inflation isn’t typically allowed. This has extreme implications.

If at some point inflation comes under control, since past price increases aren’t – on the aggregate – let to be unwound, then valuation multiples and net margin improvements to prior levels create an additional boost for the market (though in truth, very high inflation might even be able to beat low inflation in terms of nominal returns).

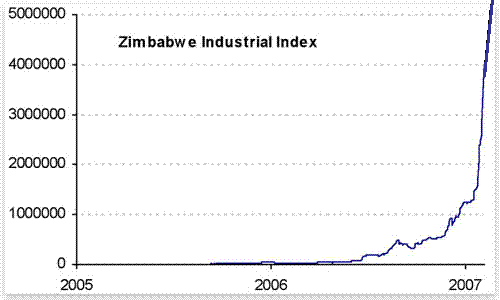

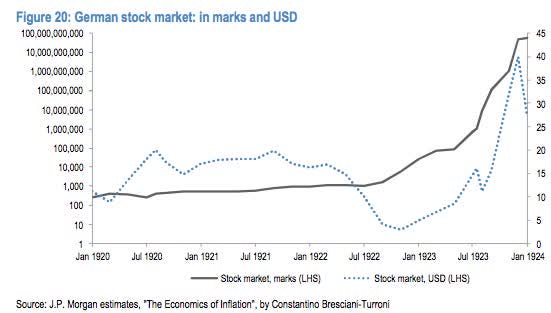

Let us just see some examples of what happens with truly high inflation. For instance, these are market indexes from Zimbabwe and Germany (Weimar Republic) during times of hyperinflation:

goldonomic.com

BusinessInsider.com, JP Morgan

Again, when it comes to nominal prices – and index levels are nominal prices – inflation isn’t necessarily a bad thing.

Stocks Are Intrinsically Inflation Hedges

Indeed, this explanation immediately shows that stocks are inflation hedges. This is so even though they can perform poorly into an inflation bout, initially, as multiples contract and profit margins might also contract.

This character is to be expected. After all, stocks are claims on productive processes and assets. Stocks represent partial ownership interests in companies producing stuff. And of course, inflation is the increase in prices of what these companies sell.

If you own 1/1000th of a company producing one billion apples, after massive 1000% inflation you’ll still roughly own the economic value of the profit of producing 1 million apples, even if the apple is now 10x more expensive. Expressed in the new, devalued, currency, that economic value will simply represent a lot more currency.

Conclusion

Over time, inflation produces higher nominal values. Higher nominal sales prices, revenues, and profits. Hence, over time, inflation also produces higher stock indexes, not lower.

Of course, in the short-term, inflation leads to higher interest rates, lower valuation multiples and potentially lower margins (in percentage terms). Hence, over the short term, inflation can produce a shock to nominal stock prices, as these adjust to lower valuation multiples much quicker than revenues and net profits get inflated. However, this is a short-term phenomenon, and inflation’s contribution to nominal stock prices (the only kind there is) is positive over time.

This ought not to be let out of sight, even as we go through the adjustment to lower valuation multiples. Inflation is a reason to buy stocks, just not necessarily immediately.

Of course, it’s certainly not a reason to buy stocks in places or companies where valuation multiples are very high and starting interest rates very low. Or, on a company-by-company basis, where inflation can destroy the economics – for instance, when the company is producing in a geography that’s inflating, and the company’s competitors sit outside that geography while still competing with it.

Finally, the higher inflation is, the quicker it can overwhelm the initial downward valuation adjustment. That said, even 10% inflation is rather slow in producing this effect. As we saw in the example, it took that kind of inflation 10 years to overcome the initial valuation and margin shock – all the while investors saw extremely negative (especially in real terms) returns from the starting point (but not from after the valuation adjustment).

This character of inflation, when it comes to its impact on stock prices, is often forgotten.

Be the first to comment