franckreporter/E+ via Getty Images

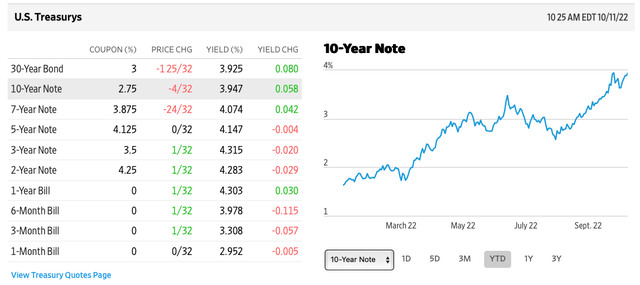

Back on January 1, 2022, the 10YR Treasury bond was yielding 1.51%. The Federal Reserve assured markets that inflation was transitory and would gradually recede. Fast forward to today, October 11, 2022, and the 10YR Treasury is flirting with 4%, the 2YR Treasury is 4.28%, and the 2s/ 10s curve is inverted by 48 Bps.

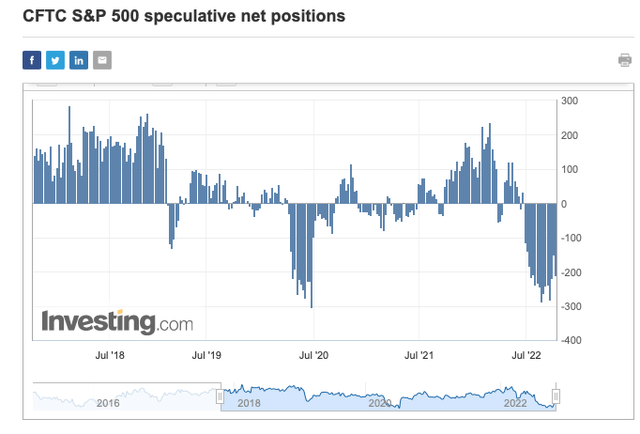

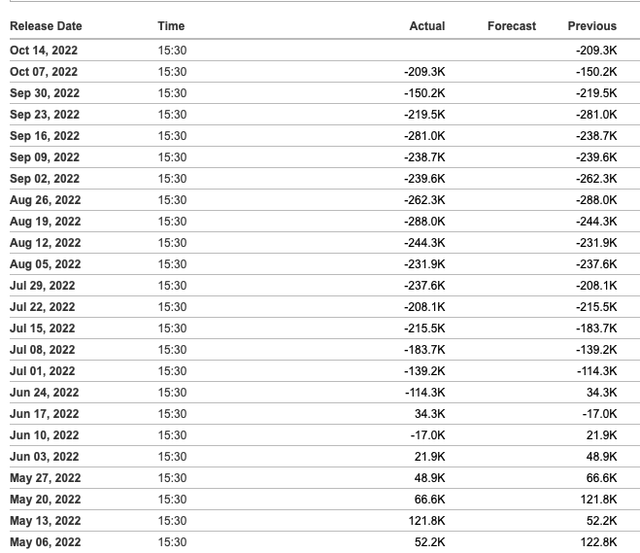

Since Chairman Powell’s late August 2022 Jackson Hole speech, hedge funds have had a field day shorting the hell out of equity markets.

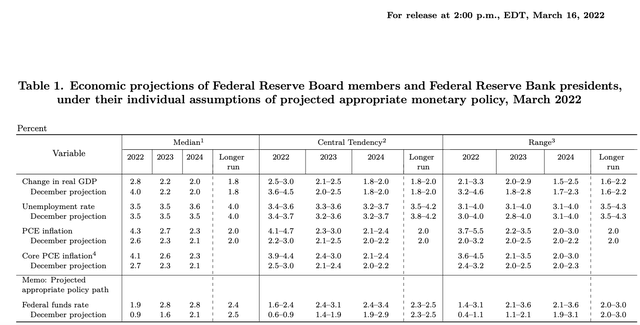

See Exhibit A below:

As rates climb, bearish sentiment moves in lock step, and equity markets have been taken to the woodshed. Year-to-date, though October 10, 2022, the Nasdaq Composite (QQQ) is down 32.6% and the S&P 500 (SPY) is down 24.2%. The U.S. Dollar (DXY) is approaching 20 year highs, which risks fanning the flames and creating conditions for a major financial blow up, most likely outside of the U.S. The world’s second largest economy, China, is on struggle street as the country tries to navigate a soft landing and housing (apartment) crash. For the first time since 1945, there is war on Continental Europe, as Putin continues to double down on a bad bet in order to save face in Moscow and St. Petersburg. As a big aftershock of Putin’s invasion of Ukraine, Europe prepares, and candidly scrambles, to replace its large reliance on Russian energy, notably natural gas. Throughout Europe, energy prices have reached astronomical levels, thus all but ensuring a recession in the U.K. and Europe as discretionary dollars get diverted to fund heating bills during winter. Not to mention what sky rocketing energy prices, in the form of natural gas, means to Europe’s robust and highly advanced industrial complexes, as significantly higher natural gas prices, on the input side, throws a huge monkey wrench into the gears of the industrial machinery.

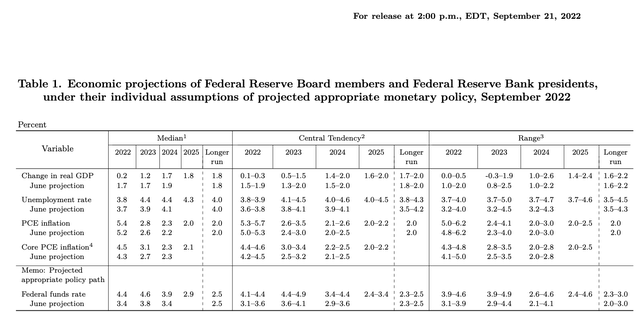

For perspective, a few and arguably lagging CPI readings combined with the Fed’s September 21, 2022 updated ‘Dot Plot’ have sent equity market barreling towards the cliff.

Incidentally, the Fed is now suggesting that its median 2023 Fed Feds rate could land at 4.6%.

The Fed’s September 2022 ‘Dot Plot’

To jog your memory, whereas back in March 2022, this very same ‘Dot Plot’ was then penciling in a 2.8% Federal Funds rate.

And by the way, just today, and for the second time, the Bank of England is intervening in the GILT market.

In the face of a what surely looks like an almost guaranteed global recession, a recession that could be wide, deep, and prolonged, it is shocking, that the Fed is so myopically focused on rear view mirror CPI data when the risk of going from way too loose policy, to way too tight policy, way too quickly is the far greater risk.

You can’t make this stuff up!

Now let me be clear here, I’m not saying that the Fed should have continued its QE program indefinitely or that its Fed Funds Rate should be pinned near zero. I actually think QE should be slowly unwound, subject to market conditions, and that the neutral rate on the Fed Funds rates should be about 2.5% to 3%. The big policy error is the signaling of its intentions to take up its Fed Funds rates to 4.6%, notably in the face of rapidly decelerating high frequency data. Just ask the CEO of FedEx (FDX) on how quickly demand signals have fallen off, and in such a short period of time!

As the financial press is geared towards first level thinking, simple narratives, and catchy sound bites, I’m not going to focus on calling out the slowing demand signals and proverbial canaries in coal mines.

Instead, I want to focus on how we go here and remind readers of what the Fed can’t control.

How We Got Here

Believe it or not, in the intermediate term, the Fed’s initial view very well might be correct, as many of the inflationary forces are transitory.

However, here’s what really happened and why so much inflation built up in the system.

Outside of world wars, Covid was one of the biggest exogenous shocks, to the global economy, in the past hundred years. It altered the would be pathway of world events and in its wake, there were tectonic shifts. Because of the heightened uncertainty and the risk of an economic collapse, policy makers, rightly so, took the Armageddon scenarios off the table. This is the tried and true playbook and Ben Bernanke just won a Nobel Prize for it. This meant take interest rates down to zero and various other forms of quantitative easing, by most central banks, globally.

Demographics, Sabbaticals (funded By Uncle Sam), The Great Resignation Movement

In the U.S., the government took a two barreled approach, as the monetary policy was reinforced by massive and unprecedented fiscal stimulus. In the end, U.S. consumers, under certain income thresholds, received three generous rounds of stimulus:

- Round one – $1,200 per adult and $500 per child

- Round two – $600 per both adult and child

- Round three – $1,200 per both adult and child

Moreover, there were a few rounds of enhanced unemployment, and a series of extensions. Specific polices varied by state, but essentially, this meant that many people who lost their jobs, notably on the lower end of the economic spectrum, received up to 100% of their pay and for an extended period of time. So if you think about it, people respond to incentives. There was an exceptional amount of stress, with schools closed, reports of people dying on a daily basis, lots of doom and gloom on the news, and peak fear. As a result, many people elected to quit their jobs and many people nearing retirement elected to retire a little early.

Secondly, suddenly folks on the lower end of economic spectrum had real savings in their bank accounts, some for the first time in their lives, and were being paid 100% of their former pay not to work. Shockingly, guess what? millions of people took sabbaticals funded by Uncle Sam. Now whether or not this is good policy, and whether or not the government erred on the side of caution and was overly generous, especially the third round of stimulus checks, is purely academic at this point. I am not going to exert any bandwidth on arguing the counterfactual. Therefore, let’s just understand and accept what happened.

Thirdly, when you have a big health crises and a major global shock, a shock that disrupts so many things, people had the time to rethink the trajectory of their lives, and not surprisingly, many people ended up making major life changes. And we can’t forget the Great Resignation movement.

So from a labor supply perspective, there was a major catalyst for people not to work in the form of stimulus and extremely generous enhanced unemployment benefits, a number of folks nearing retirement pulled the ripcord one to a few years earlier than they might have planned otherwise, and then we had the Great Resignation wave. Therefore, all of a sudden, somewhat balanced labor market, from a supply and demand perspective tilted to under supplied. When large swaths of the U.S. economy are short on labor, businesses become less efficient and they need to pay more to attract and retain key personnel to keep the lights on and business moving.

This leads to inflationary conditions.

So let’s be crystal clear, the Fed jacking up its Federal Funds rate from zero bound to 4.5% isn’t going to change the demographics of the country, with the Baby Boomer cohort, upwards of 76 million people, born between 1946 and 1964. The Fed simply can’t turn back the hands of time. It is estimated that roughly ten thousand baby boomers turn 65, every single day. If people want to retire, and they have the economic means, the Fed’s policies can’t change this. And therefore, from a supply and demand perspective, at the margin, there is a strong tailwind for labor as there is less supply.

In terms of the Great Resignation and Uncle Sam funded sabbaticals, eventually, the savings run out, and people need to get back work. No question, when people leave various careers, often on the lower rungs of the economic ladder, to go back to school, pursue a trade, or in search of greener pastures, it takes some time for employers to be able to improve the attractiveness of unfilled jobs in order to get back to a full roster of people.

The Demand Side Of The Equation

As a result of this extraordinary amount of stimulus, you had tens of millions of people with excess savings, who were stuck at home for a multitude of reasons, and many of them decided to spend some of that money.

What happened?

Well, demand surged! Unfortunately, though, the global supply chain was ill equipped to meet this sudden and prolonged surge of demand. Moreover, China’s zero Covid policy led to severe bottlenecks and major factory stops and starts. Essentially, and what made matters worse was years of B school doctrine of ‘Just in Time’ inventory management which meant many companies no longer built redundancies into their supply chains. In addition, given the initial severe drop in demand, many creators/ sources of capacity slashed that capacity, in the immediate aftermath of Covid, think March and April 2022. And to make matters worse, there was a major chip shortages, as surging demand couldn’t be met, and this led to end customers and companies double or triple ordering chips, which in turn further exacerbated matters. These robust price signaling, in the form of record new orders, led to spiking of prices, as after all, who wants to let a good crisis go to waste? Lastly, and I’m greatly condensing my explanation, coming into Covid, shipping had been a horrible industry, with many boom and bust cycles, but mostly bust. As many shippers were on their back, from a balance sheet perspective, the supply and demand of ships was relatively balanced entering this period, so again not a lot of excess capacity per se (as it had been scrapped or it was rendered obsolete). And as there are long lead time for new builds, you can’t simply flip a switch and produce more ships. Moreover, the bigger issue was that the velocity of supply chain was greatly reduced by lack of dock workers, on both sides of the globe (think Asia and the major ports located West Coast of the U.S.) as well as a shortage of truck drivers, essentially creating a major and long lasting supply chain cluster/ outright mess.

So if you play out the logic, we had Covid lead to more retirements than would be expected and millions of people taking government funded sabbaticals via enhanced unemployment / three rounds of stimulus. This led to a shortage of workers and the only way to attract the marginal worker back, to meet this surging demand, was to offer them more money in the form of signing bonuses, retention bonuses and higher wages. This in turn, albeit with a lag, led to these cost being pushed through and ultimately passed on in the form of higher priced of goods and services. Also, skyrocketing, think upwards of 20X increases, in container ship costs and major supply chain delays also led to this record inflation.

The Final Icing On The Cake (Spiking Oil, Leading To Record Nominal Gas And Diesel Prices)

As what often happens, when things are vulnerable, and usually at the worst time, another negative shock invariably seems to occur. The last major shock was Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Suddenly, for the first since 1945, there was war in Continental Europe. Most of the world, including major think tanks and purported Phds, folks from the world’s most well regarded institutions, didn’t see this coming or simply underestimated the boldness / craziness of Putin.

This war led to a surge in oil prices, with front month oil contracts approaching the upper $120s. Making matters worse, this happened a few months in front of the 2022 summer driving season and while the economy was set to reopen, coming out of the fog of Covid, and coinciding with the great re-opening/ back to the office, a major driver of demand for gasoline.

So, and given years of under investment due to the ESG pressures, a major war premium was placed on hydrocarbons, and the U.S.’s lack of refining capacity meant gasoline prices got past $5 per gallon and even reached the upper $6s, per gallon, for diesel. Diesel is what powers the big fleet of trucks and trains that move those goods and physical commodities. The record diesel prices led to big surcharges, and again, those costs always get passed through, ultimately showing up in the form of higher food, and prices. Another name for higher prices is inflation.

Putting It All Together

Just to be clear, I’m in agreement that the Fed needed to take up its Fed Funds rate from zero bound to neutral. However, and this a major point of distinction, I would argue neutral is closer to 2.5% to 3%. Of course, the Fed needs to gradually reduce the size of its balance sheet, subject to market conditions. However, I would strongly argue that actually taking its Fed Funds rate up, this rapidly, to 4.5%, would be ludicrous in the face of a host of slowing high frequency data points and major global shocks. China has a very real housing (apartment) market decline that threatens its banks, Europe has a major energy shock crisis and an economic bloc that seems to perpetually under perform its potential for the better part of two decades now (a subject for another day), and who knows what secondary and tertiary after shocks await markets as a surging U.S. dollar, near twenty year highs, tend to fan the flames of inflation outside of the U.S. and, at least at the margin, increases the risk of a sovereign debt crisis.

In closing, I hope people and policy makers slow things down and take some time to reoriented themselves with the true oceanic forces that caused inflation and understand that many of them can’t be bent to the will of the Fed. It is time for the Fed to stop tilting at windmills and to look past short term, admittedly highly elevated, CPI readings. It is just way too dangerous for the Fed keep the pedal of the sports car pinned down to the floor as navigating upcoming both narrowing and winding sections of roadway ahead is far more difficult at its potential ‘peak’ velocity. The risk of unintended consequences far outweighs the short-term and optical benefits of slaying inflation. Perhaps, market forces have already slayed peak inflation, and it just hasn’t shown up yet in the data.

Be the first to comment