Yingko/iStock via Getty Images

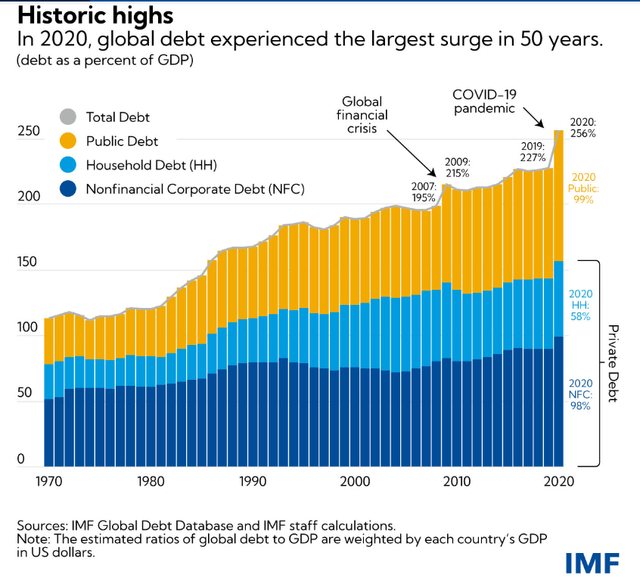

Investment thesis: Despite widespread expectations of debt deleveraging following the 2008 financial crisis, the world’s debt-to-GDP ratio continued to increase, with a massive leap following the COVID outbreak.

The surge in global debt coincided with a steady trend of global interest rate declines since the early 1980s. The decline in interest rates led to a steady increase in the global debt-carrying capacity. Now that the four-decade trend of declining rates has reversed, the global debt-carrying capacity as a percentage of GDP is set to shrink, even as the natural tendency will be to continue expanding debt. The inevitable outcome will be massive defaults, while consumers will likely enter a prolonged period of pulling back on unnecessary discretionary spending. This all presents investors with a unique challenge with no precedent to draw on as a reference for the investment career of most investors. It is, therefore, reasonable to assume that past strategies will be ill-suited for the challenge ahead.

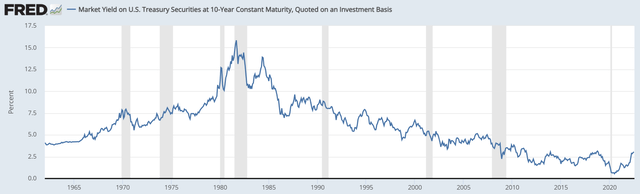

Four decades of declining interest rates come to an end, leaving a massive debt hangover behind.

US historical 10-year bond yield (FRED)

As we can see, since the early 1980s a steady decline in interest rates commenced. The U.S. 10-year yield tends to be a good proxy for global interest rate trends. A number of factors helped to usher in this long era of what will become known as the period of debt-fueled growth. First and foremost, this was the great era of globalization, which led to a drastic increase in specialization of production that led to a fall in prices, especially in manufactured goods.

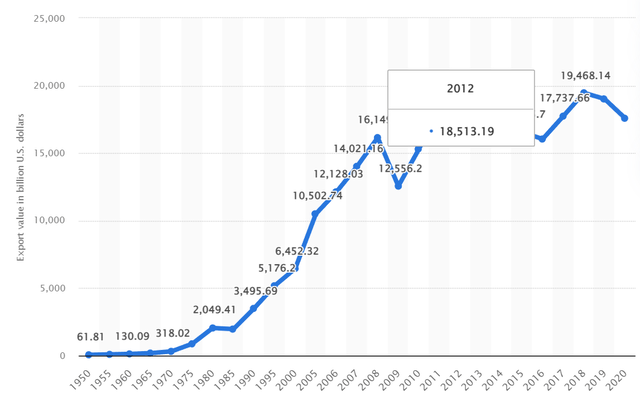

Global trade volume measured in USD (Statista)

The outsourcing of manufacturing from the developed world to the developing world helped companies to increase profitability, while the global economy was flooded with a seemingly interminable supply of manufactured goods. The process was supported by a steady and sufficient production increase in critical natural resources that were needed to sustain the creation of a demand-side economy. In other words, as long as demand could be created supply was always there for pretty much anything the global consumers wanted to consume.

It should be noted that the trend of declining interest rates fed on itself to some extent. As the cost of servicing debt began to decline, companies passed on some of the debt-servicing savings to the consumers. It is important to understand the role that the factors I mentioned played in making the world of declining interest rates possible because we are now seeing all of the three above-mentioned factors run in reverse. It is, therefore, reasonable to expect these same three factors to lead to higher inflation, which will, in turn, lead to higher interest rates. In other words, the uptick in interest rates we are seeing is not just another short-term upward blip like we have seen many times in the past four decades. The bottom in interest rates we saw during the COVID downturn is likely to be the all-time bottom in interest rates, with inflationary pressures set to keep the trend from trending that low for the foreseeable future.

At the root of the inflationary cycle, we are faced with is a sustained commodities boom. At the root of the commodities, boom is a geological reality, which in my view is the most important fact that is shaping economic and geopolitical events this decade.

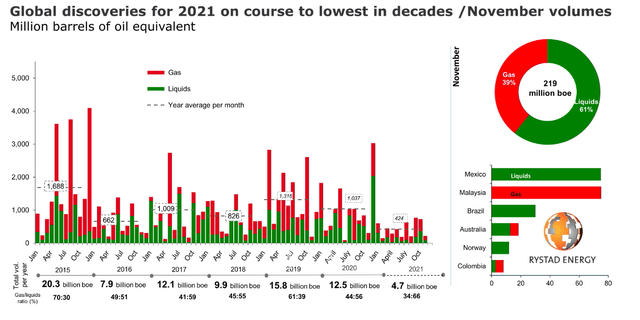

Global oil & gas discoveries (Rystad)

The reason why I believe this to be the most important fact this decade and perhaps beyond is that the world is currently consuming roughly 45 billion barrels of conventional oil equivalent in oil & gas per year. In other words, last year we may have discovered about 5 billion barrels of oil and gas, while we consumed about nine times more. This number is not a fluke, as the chart shows, we have been falling far short in this regard every year. Nor is it a matter of the global oil & gas industry not trying to discover more resources.

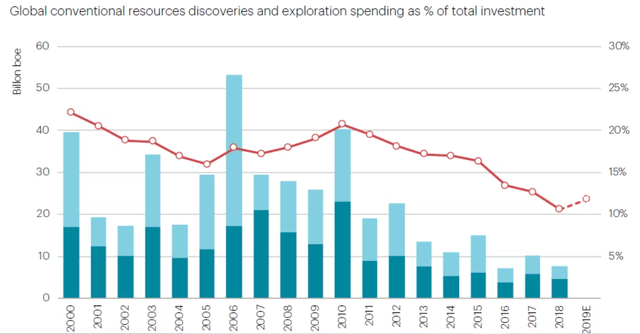

Global oil & gas discoveries versus exploration spending (IEA)

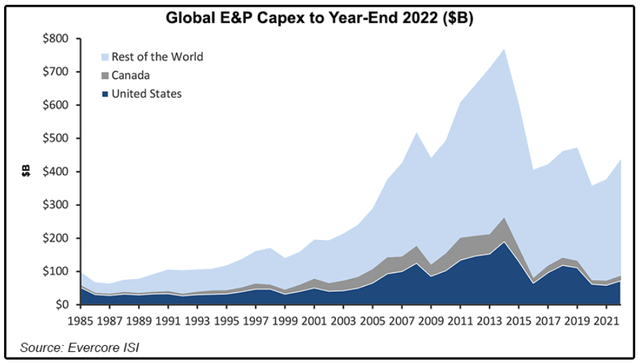

Charts such as this one from the International Energy Agency (“IEA”) may provide the correlation necessary to make the lack of spending argument until we actually look at total upstream CAPEX spending.

Global E&P spending by year (NGI)

When looking at the two charts, we can conclude that since the year 2000, we have been spending more on average on oil & gas exploration than we did in the 1985 to 2000 period. Despite that, we are coming up short on discoveries versus production in conventional oil & gas almost every year so far this century, and there are no prospects of improvement going forward. If anything, it will only get worse and it is a matter of geology, not capital spending. All the years of discoveries not coming anywhere near matching yearly production are starting to catch up to us. We were able to muddle through on enhanced recovery of excess resources in place that we discovered in the 20th century for a while, but it was never going to last forever.

If we go back to the whole idea of the demand-driven economy, where production seemed to be limitless, therefore not an issue for the past few decades, clearly we are no longer in a situation where we can still count on commodities-extracting companies to match consumer demand. We entered the era of scarcity. It can be partially overcome through technological and other factors that can provide gains in efficiency, but it will never be completely neutralized. Furthermore, it seems that scarcities tend to trigger geopolitical confrontation, which plays a secondary-effect role in further exacerbating the scarcity problem through disruptions to the global supply chains. All this is inflationary and it will play a role in squeezing borrowers, as the costs of borrowing throughout the global economy will trend upwards.

Inflation is already leading to more defaults and bailouts. Higher inflation rates will combine with rising interest costs to deliver a one-two punch to the gut of the global economy.

We are not yet at the point where higher interest rates will trigger an explosion in defaults and failures. Right now, we are still in the first stage of the crisis, where inflation is starting to squeeze the debt-carrying capacity of the weakest borrowers. For instance, subprime borrowers in the U.S. are starting to fall behind on their payments at an increased rate, as other non-discretionary consumption costs such as energy and food increased significantly in the past year.

In Europe, many major energy companies are finding it hard to survive the dramatic rise in energy prices, which they are not always able to pass on entirely to the consumers. Uniper (OTCPK:UNPRF) was just bailed out by the German government, with almost 17 billion euros and it gives the German government a 30% stake in the company as a result. France’s EDF (OTCPK:ECIFY) may see a takeover of the remaining 16% stake in the company that is still not government-owned, for about 8 billion euros. High inflation is also starting to pressure some sovereign states into default, as we saw with Sri Lanka, which defaulted this year.

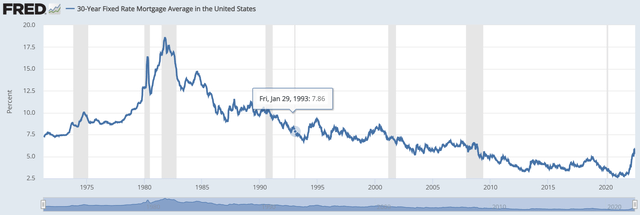

The inflationary pressures on borrowers represent just the first stage in the crisis, and we are just starting to see the beginning of that first stage this year, where borrowers at all levels, including consumers, corporate entities as well as sovereign states are starting to feel the squeeze. The effects of higher interest rates will only start to be felt perhaps in a year or two as old debts are refinanced, while new debt is taken on at much higher interest rates. For instance, mortgage rates are currently at highs not seen since 2008.

30-year fixed mortgage rates (FRED)

Most mortgages currently outstanding are in no way affected by the recent rise in rates. Only new borrowers, as well as those stuck in some form of a variable rate policy, are being affected, which currently makes up only a small portion of all outstanding home loans. But with every month that passes, the ratio of loans being affected will grow, therefore the net average burden on all home mortgage policyholders is on the rise, even if very gradually.

The rise in interest rates will be far less gradual at corporate and government levels. Every year they need to roll over massive amounts of debt, which from now on will be done at higher interest rates. Any new debt will also be issued at higher interest rates. It should also be noted that within the current context those entities which are set to greatly increase their total debt levels are likely to see a drastic re-calculation of their risk factor, making it more likely for them to see additional interest rate pressures.

For every 1-point rise in the average interest rate that the world needs to pay on its outstanding debt, we will see an increase in debt-servicing costs of about 2.6% of total global GDP. At the moment that would mean an extra $2.6 trillion (give or take) in added interest costs globally. Some may argue that even though interest rates are headed higher, the fact that it is mostly due to higher inflation, may mean that we are set to see our debts inflated away, meaning that the global debt/GDP ratio should shrink. Right now, there is no evidence that this will happen.

Inflation is also squeezing the profit margins of companies, the costs of government services, as well as the finances of consumers. The inflation factor may, if anything leads to a further long-term rise in the global debt/GDP ratio, not a fall, as everyone tries to keep up with needs that are increasingly priced higher, even as incomes will not keep up. The end result will therefore be more debt that will be more and more expensive to service. At some point, probably within the next few years, the trend of higher debt, that will cost more to service, will give way to a re-balancing, where the debt/GDP ratio will start to fall, giving way to a very painful period in World history in economic terms.

Investment implications:

The implications of this thesis, assuming that it turns out to be more or less right are endless. There is one unavoidable conclusion that can be drawn, namely that we are headed for a very tough investment environment in the coming months, years, and even decades. As I pointed out in a recent article entitled “Echoes Of Ceausescu’s Scarcity Economy Means Investment Strategy Rethink Is Needed,” I changed my investment strategy dramatically this year as a result. I am actively seeking diversification, as much as possible, as the reality of this investment environment is that it is full of landmines.

Among other things, I am trying to do my best to avoid accumulating outsized positions in any given individual stock. I am doing my best to keep most new stock positions at less than 3% of my total portfolio at the time of acquisition. I am also trying to avoid sectoral overweighting, within reason and I am trying as much as possible to achieve some geographical diversification. On the latter goal, at this point in time, my positions are heavily skewed toward U.S. and Canadian stocks, with only a minor position in European and Asian assets.

I find European assets particularly risky at this point on geopolitical concerns, given that they will bear the brunt of the proxy war with Russia, including the economic war’s blowback. Some physical gold & silver is a way to diversify away from paper assets altogether, and it is something that looks increasingly attractive as an investment option, within the context of investing becoming increasingly a means to try to preserve wealth, rather than a way to get ahead. Gold has a very long history of being a wealth-preservation asset and right now it is an asset I do not mind being a bit overweight on.

An inflationary economic environment presents a tough market to navigate through, as we have been finding out in the past year. Rising interest rates are supposed to be the cure. My take on it is that it will not be a very effective cure, given that inflation is driven by scarcity fundamentals that cannot be easily solved due to geological, geopolitical, and technological constraints. Higher interest rates will have only a moderating impact on inflation, while it may have an outsized impact on the economy and on debt delinquency rates. Rising interest rates will therefore become yet another challenge for the economy and for investors. As more and more old debt will be rolled over and refinanced at higher rates, the negative effects will take on an exponential aspect, hitting profit margins in the private sector, hitting government spending and also hitting the consumers very hard going forward. In other words, it will get progressively worse in the years to come for investors trying to navigate through it all.

Be the first to comment