Tast Nawarat/iStock via Getty Images

Globalization is besieged on multiple fronts. Two years after the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic and amid growing geopolitical unrest, the decades-long disinflationary headwind has reversed. Many multinationals have taken steps to address the associated disruptions to their expansive and hyper-optimized but ultimately brittle global value chains.

These institutions are re-orienting their focus to prioritize availability over cost-optimization. This process manifests in three ways:

- Regionalization: moving supply chains closer to key markets.

- Nearshoring: shifting supply chains to neighboring centers of production.

- Reshoring: reversing, in part, the cost-saving offshoring of previous decades.

Inflation is one key consequence of these shifting priorities. Reorganizing far-flung global manufacturing hubs into redundant regional supply chains demands increased capital investment and resource expenditures on everything from logistics to management. Such improvements cost money, and consumers will ultimately pay higher prices in return for more reliable supply chains.

Furthermore, the globalization process and the increasingly efficient resource allocation of the last several decades hinge on the geopolitical stability of the post–Cold War era. The collapse of the Soviet Union and China’s entry into the World Trade Organization (WTO) enabled cost-convergence between once-segmented commodity and labor markets. This created disinflationary pressure in the advanced economies. In retrospect, the Iron Curtain was a significant barrier that kept bountiful grain harvests and energy resources from developed economies.

Nevertheless, as cracks develop along geopolitical fault lines, new obstacles could emerge to disrupt global trade. The “peace dividend” of the last 30 years could erode further: Blockades, embargos, and conflict could create costly supply chain detours.

An Inflation “Paradigm Shift” Constrains Monetary Policy

Against the backdrop of the Russia–Ukraine conflict and prolonged pandemic-related disruptions, Agustín Carstens, the general manager of the Bank for International Settlements (BIS), recognized that “structural factors that have kept inflation low in recent decades may wane as globalisation retreats.” He continued:

“Looking even further ahead, some of the structural disinflationary winds that have blown so intensely in recent decades may also be waning. In particular, there are signs that globalisation may be retreating. The pandemic, as well as changes in the geopolitical landscape, have already started to make firms rethink the risks involved in sprawling global value chains. And, regardless, the boost to global aggregate supply from the entry of some 1.6 billion workers from the former Soviet bloc, China and other EMEs into the effective global labor force may not be repeated on such a significant scale for a long time to come. Should the retreat from globalization gather pace, it could help restore some of the pricing power firms and workers lost over recent decades.”

Under Carstens’ framework, a paradigm shift on inflation is also a paradigm shift on monetary policy. The major central banks have had significant operational freedom to engage in unconventional monetary easing — money printing — thanks to globalization’s disinflationary effects. Renewed inflationary pressure could shift this dynamic into reverse. Rather than apply quantitative easing (QE) in response to virtually all downside shocks, central bankers would need to calibrate future support to avoid exacerbating price pressure.

Yield Curves Forecast Monetary Policy Rather Than Recession

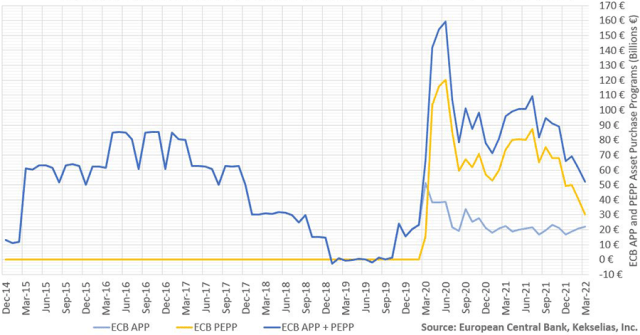

Despite these changing circumstances, both the European Central Bank (ECB) and the US Federal Reserve maintained interest rate suppression policies well into the supply-led inflation spike. Monthly ECB bond buying totaled €52 billion in March 2022 as the eurozone’s Harmonised Index of Consumer Prices (HICP) reached 7.5% year over year (YoY). As the Fed slowed QE flows in February, personal consumer expenditures (PCE) were already at 6.4% YoY. Despite QE’s role in suppressing long-maturity bond yields, the ECB’s 2022 purchases will fall to €40 billion in April, €30 billion in May, and €20 billion in June, before halting “sometime” later.

ECB Asset Purchase Program (APP) and Pandemic Emergence Purchase Program (PEPP)

QE programs have anchored long-term global interest rates and co-movement between European and US long-term yields. Lael Brainard of the Fed’s Board of Governors recognized foreign QE’s ability to lower US long-term bond yields. Thus, expectations of rising Fed short-term rates amid ongoing foreign QE contributed to the inversion of the US 5s30s Treasury yield curve.

Vineer Bhansali, the CIO of LongTail Alpha and author of The Incredible Upside Down Fixed-Income Market, also noted how policy affects the yield curve. Since central banks can influence all points on the curve through QE, the shape of the yield curve reflects the policy outlook rather than the likelihood of recession. As Bhansali said:

“The first and most important signal that the Fed has distorted is the shape of the yield curve. Yield curve inversions, in particular, are well known by market participants to be a reasonably good predictor of recessions. Historically, that is. Right now, the Fed owns so many Treasuries that it has the power to make the yield curve shape whatever it wants it to be.”

To add to Bhansali’s framework, an inverted yield curve embeds the expectation that rate hikes will slow the economy as inflation declines and disruptions ease, thus freeing central banks from policy constraints — a convergence toward pre-2020 “old normal” — which would lower the hurdle of renewed QE to suppress long-maturity yields.

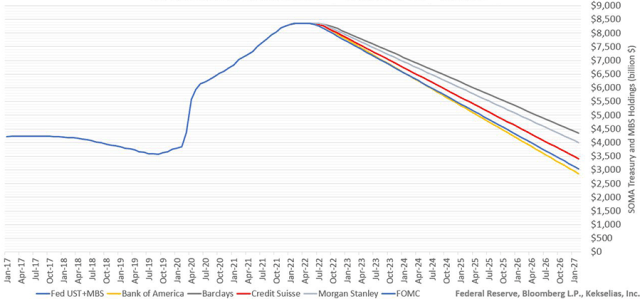

Conversely, an inflation regime change propelled by a more fractured world with scarcity-led reflation demands a reversal of balance sheet expansion, or quantitative tightening. The Fed’s guidance as to how it would unwind its balance sheet — at $95 billion per month — exceeded many bond dealers’ expectations.

Fed Balance Sheet Unwind Scenarios, Pace in Lieu of Composition Shift

Expansive Supply Chains Drive Inflation (And Policy)

As geopolitical instability disrupts once-efficient resource allocation, the relative peace and prosperity of the last 30 years is being reassessed. Could the lack of major power rivalries over the last several decades be the exception rather than the rule? And if the atmosphere deteriorates further, what will it mean for today’s globalized value chains?

This framework suggests the potential for supply-led inflation rather than disinflation. Further unrest could fuel a de-globalization process of supply chain regionalization and retrenchment that boosts inflation. Yet, a less expansive supply chain may have benefits from re-expansion once disruptions cease and inflation falls.

In market terms, the current bond yields in developed countries cannot fully compensate investors should markets fragment further. Carstens’ theory of an inflation paradigm shift leading to a monetary policy paradigm shift implies significant risks to long-maturity bonds assuming a worsening geopolitical outlook and further supply chain disruptions.

Disclaimer: Please note that the content of this site should not be construed as investment advice, nor do the opinions expressed necessarily reflect the views of CFA Institute.

Editor’s Note: The summary bullets for this article were chosen by Seeking Alpha editors.

Be the first to comment