Vladimir Zapletin/iStock via Getty Images

Introduction

This article describes a more stable channel for the flow of funds from savers to short-term corporate borrowers – an alternative to the regulation-crippled existing channels through which wholesale short-term debt flows to retail and institutional investors today.

You can find my description of the regulations that have choked the flow of short-term funds here.

After describing the effect of regulation on the market’s transfer of funds from investors to short-term borrowers, the article considers what is missing from the current system and supplies a fix.

The status quo

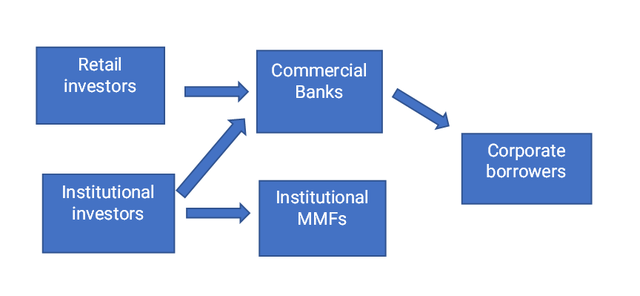

The existing conduits,

- the market-priced solutions provided by wholesale deposit-based bank finance and prime money market funds (Prime MMFs, henceforth in the article MMFs)

- and the nonmarket solution provided by commercial banks and other commercial lenders offering loans indexed by LIBOR

were once serviceable answers to the perennial problem of short-term private sector debt illiquidity.

The stable bank deposit-based channels for short-term savings flows put the risk management decision in the hands of the banks. Historically this channel of investment funds has been robust to increasing interest rate risk once the savings and loan crisis awoke the system to the magnitude of interest rate risk. Importantly, the deposit-based system replaced the credit risk of corporate paper issuers with a much lower bank credit risk.

The flow of short-term debt before the regulations. (author)

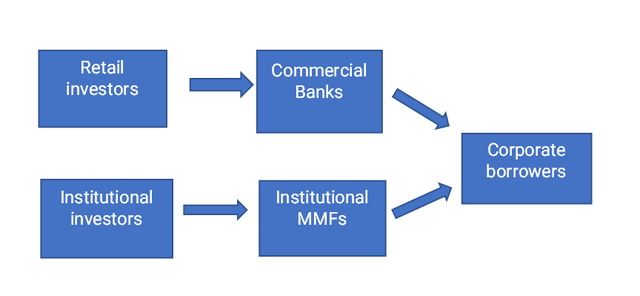

But no more. In the wake of the 2007 Financial Crisis, regulators squeezed the banks’ access to the wholesale deposit market to a trickle with new capital charges aimed at reducing wholesale deposit-taking.

Short-term debt after the regulations (author)

This left MMFs without competition from the more stable system of wholesale bank deposit-based funding. Regrettably, MMFs have proven too unstable to be a reliable source of funds during the now regularly occurring financial crises. MMFs have proven to be easily toppled, risky instruments – an inadequate primary channel for the flow of an important share of private sector short-term funding, especially when markets are volatile.

The markets need a safer version of the MMFs. To become safer than MMFs, this new alternative could take its cue from the more stable but now regulation-impaired system of wholesale bank funding, improving on the wholesale bank funding model by using capital more efficiently, thus avoiding regulatory objection.

The short-term private sector credit markets have become unreliable. Both market funding, through commercial paper and wholesale deposits, and nonmarket funding, such as credit card borrowing, based on credit market indexes have become problematic.

Our private-sector short-term credit markets are dysfunctional

There have been two related regulatory initiatives that changed the way the short-term private debt market functions, regulatory curtailing of wholesale deposit issuance, and regulation of the MMFs.

Bank regulators have added capital restrictions affecting wholesale deposit issuance, the liquidity coverage ratio (LCR), and the Net Stable Funding ratio (NSFR) to reduce the risks to banks of deposit issuance by curtailing issuance itself.

The new capital charges have choked off much of the flow of funds to private sector borrowers through the banking system, increasing the flow of money through the now-overloaded much riskier MMFs.

These post-financial crisis regulatory initiatives designed to prevent future bank collapses, promulgated following the Financial Crisis of 2007, have instead sharply curtailed the efficiency of the banks in normal conditions.

And judging by the frequency of market failures, regulatory fixes of the MMFs have done nothing to eliminate market collapse.

Moreover, there has been no private sector reaction – nothing has replaced the weakened wholesale deposit-based system that once reliably transferred savings to private sector borrowers.

There is no appropriate index for pricing nonmarket credit

A closely related problem is the now inefficient flow of savings through non-market priced channels from savers to private sector borrowers. The demise of the London Interbank Deposit Rate (LIBOR) has limited the ability of lenders and borrowers to index non-market transfers of savings into corporate investments at an appropriate interest yield – a yield that reflects the current market cost of term private sector credit.

Only the private sector can implement a positive solution

Regulators can only tinker with existing markets. Both regulatory initiatives:

- Curtailing wholesale deposit issuance

- Promulgating regs that reduce the profitability of using MMFs

are problematic.

These regulatory measures, like any regulatory measure, are inevitably a limiting factor, not an enabling one. The folding of the wholesale bank funding channel has encouraged investors’ sole dependence on the MMFs which experience crippling redemptions at the drop of a hat.

The regulator’s concern for the stability of the market in times of crisis is not tempered by concern for the profitability of the financial institutions that intermediate between saver and investor during both normal and chaotic markets.

That is why the private sector is inevitably the only source of financial innovation that can reliably replace the regulator-hobbled existing system of short-term private debt transit.

What does a stable private sector system look like?

A more stable short-term market-priced debt instrument

The market for short-term money has become a market serviced by Prime MMF boutiques without an Amazon-like general source of short-term investment to service the more pedantic daily needs of most wholesale investors.

The MMFs are for-profit investment funds that compete on both safety and yield in an environment of razor-thin margins. This competition of MMFs for the investor dollar puts a premium on higher yield. But the reach for systematically higher yield is inevitably going to inspire some MMFs to take a greater risk.

What is needed is a fund that thrives on volume at the expense of yield. The boutiques that are MMFs can take risks, and fail sometimes, without creating systemic problems, in the presence of a larger more stable fund that provides an average yield based on a market-wide selection of high-quality short-term commercial paper. The fund would cede the reach for a higher yield to the risky MMFs. It would compete instead with greater liquidity and greater stability. The fund’s incentives would exclude it from joining the reach for a higher yield.

The ideal instrument would be homogeneous, a reflection of the entire market – not hostage to the whims of issuing firms as are MMFs – and would ideally be managed by a clearinghouse with no net long or short position, hence no conflict of interest in determining the instrument’s value.

The byproduct: a stable index of the market-determined cost of term debt

A beneficial side effect of the successful exchange trading of this new more stable type of financial instrument is that an index with the desirable properties of LIBOR, but without its problems, would also be created.

The hidden cost of LIBOR replacement by SOFR

What was lost with the regulatory decision to eliminate LIBOR, the benchmark cost of short-term unsecured debt? The financial market regulators’ answer is that an index of the three-month cost of money was simply replaced with a more liquid one. Their solution is the three-month Secured Overnight Financing Rate (SOFR). The regulators’ position is that SOFR-based pricing will satisfy the needs of investors and borrowers.

Three-month SOFR is not a three-month rate, but a geometric average of past overnight Treasury-collateralized interest rates – or repo rates. Thus, short-term debt using SOFR is not available at the market-determined price of short-term private sector debt.

In a regulator-coerced SOFR-only indexed market, every major short-term investment must be priced against a Treasury-based interest rate formula. Short-term private funds are transferred at an index yield calculated using market-determined rates, but these market rates have nothing to do with the credit risk firms that borrow and lend at SOFR are facing.

The coming market tests

Financial market liquidity in short-term debt markets is once more in short supply as changing inflation and more volatile economic conditions pressure financial markets.

Financial market participants cower as the markets return to the risky financial environment of the late 1970s and early ’80s when the two-edged sword of rampant inflation and the tardy onslaught of tight-money-created volatility and ultimately a major recession became a reality. Will the Fed need to prop up the MMFs again?

It is a forlorn hope of some market participants that regulators will bring back LIBOR, the summary estimate of the cost of three-month wholesale deposit money provided daily by a panel of large banks, but LIBOR’s doom was sealed by the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit’s Jan. 27 reversal of the convictions of two former Deutsche Bank AG traders accused of rigging Libor in U.S. v. Connolly. The court held that because there was no single proper interest rate; the Libor instructions leave open the possibility of multiple proper interest rates on a given day.

This legal outcome determined that indexes based on opinion are no longer viable. A daily vote cannot serve as a global index of the cost of short-term unsecured debt.

Indexes that compete with SOFR, for example, the Bloomberg short-term bank yield index (BSBY), could produce index values that meet regulatory requirements so long as the markets for the instruments whose prices are used to create the index are available. In times of market crisis, MMFs can make no such promise, undermining BSBY.

Conclusion

There is no turning back. The role of banks in intermediation is being assumed by trading firms and markets. This appears to be more than a reaction to bank over-regulation but instead a substitution of computer-based algorithm-driven decision-making power for human capital-intensive decision-making.

And LIBOR was never a particularly robust answer to the question, “What is the market cost of short-term credit risky money?” Opinion-based indexes, rest in peace. Let the market determine the price of private sector credit.

But the replacement of bank-managed intermediation with market-based intermediation is a cheaper way to restore the markets for short-term private sector debt. Exchange intermediation is cheaper than bank intermediation in a mass marketplace like the commercial paper market because exchanges reduce the need for capital by an order of magnitude. And in the unbiased hands of an exchange clearinghouse, a robust replacement for LIBOR with characteristics regulators demand is possible.

Be the first to comment