SimonSkafar

Italian multinational energy company, Eni S.p.A. (NYSE:E) is one of the stars of the energy market. The company has been a winner during the stock market collapse, rewarding investors after years of underperformance. Future profitability is likely and is supportable, given the exit of capital and renewed capital discipline across the industry. Rather than being subject to a boom-and-bust trend, investors in energy stocks, and Eni in particular, are likely to enjoy smoother return profiles.

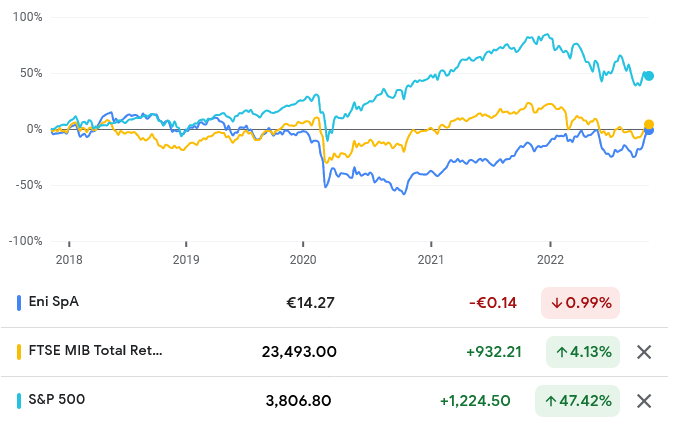

In the last five years, Eni has been a terrible investment proposition for investors, with the share price declining 0.99% across that period, while the FTSE MIB (the benchmark index for the Borsa Italiana) rose 4.13% and the S&P 500 rose 47.42%.

Source: Google Finance

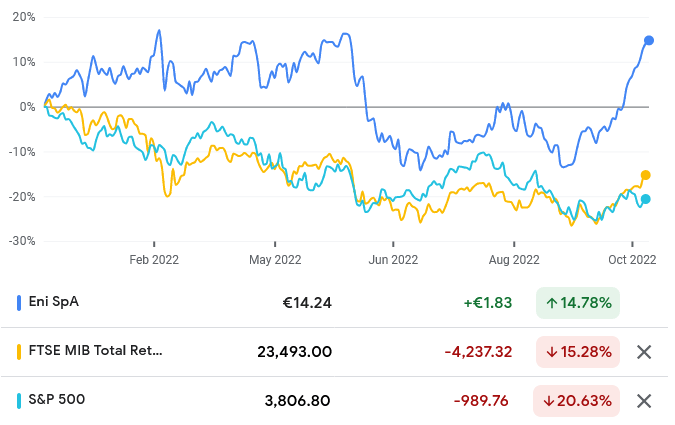

Nevertheless, in the wake of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, and post-pandemic dislocations of supply chains, oil & gas prices have taken off, and with them, energy stocks. In the year-to-date, Eni is up nearly 15%, while the FTSE MIB is down over 15% and the S&P 500 is down nearly 21%.

Source: Google Finance

Oil & Gas’ Profitability is Sustainable

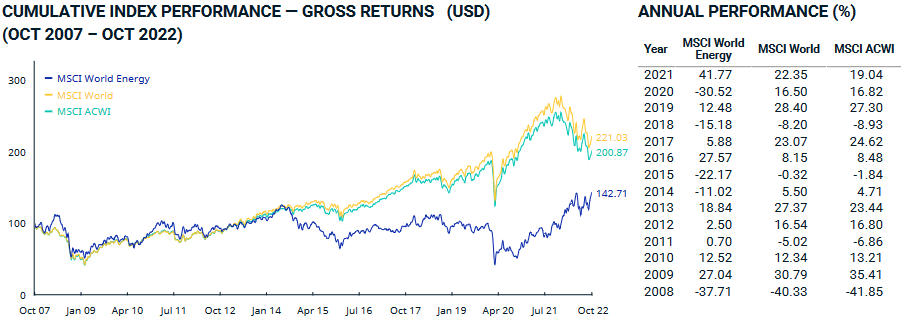

In the wake of the Great Recession, the energy markets have destroyed investor capital with wild abandon. In the last decade, the MSCI World Energy Index has returned just 4.39% per year, compared to 9.52% for the MSCI World, and 8.54% for the MSCI ACWI. That pattern of underperformance goes back as far as 2006.

Source: MSCI World Energy Index

However, in 2021, the MSCI World Energy Index grew by 41.77% compared to 22.35% for the MSCI World, and 19.04% for the MSCI ACWI. In the year-to-date, the MSCI World Energy Index is up 47.91%, while the MSCI World Index is down 19.74%, and the MSCI ACWI is down 20.81%.

While “inflation” is a decent explanation for what’s going on, the sustainability of the industry’s profitability given a boom, has never been a given. Typically, high returns attract capital, with managers tempted into growing their asset base, and expanding production, in order to maximize their returns. Unfortunately, what is rational at the micro level turns out to be irrational at the macro level, and the decision by managers to expand capex leads to an oversupply of oil & gas, and from there, a bursting of the bubble. Capital, once attracted to the industry, is now repelled by it, and exists until such a point where profitability returns to the industry. This phenomenon has been described by Marathon Asset Management as the “capital cycle”, and in academic literature, it is described by the asset growth effect. The asset growth effect refers to the inverse relationship between asset growth and future abnormal returns, which sees low asset-growth firms enjoy superior abnormal returns to high asset-growth firms. Thus, the low returns of the energy industry post-Great Recession are a function of the asset growth effect. For investors, the question is: will returns plummet as they have historically done?

While OPEC+’s decision to symbolically cut production despite President Joe Biden’s urgings to expand it, has been explained as support for Russia, there are strong economic reasons for saying no to the United States: demand has been sluggish, especially from a China that remains committed to a zero Covid policy, which the Chinese government has described as a “policy of greater benevolence 大仁政”. Expanding production would reduce prices without increasing Chinese demand. OPEC+ has also had to weigh the consequences of going against Russia, and having Russia have an independent oil policy that would hurt their interests. Finally, a policy to go against Russia would not succeed because there is not enough spare capacity to make up for the loss of Russian oil.

Thus, we are in a unique moment where high oil prices are unlikely to be met by expansion in production, and the kind of capital destruction that invariably follows.

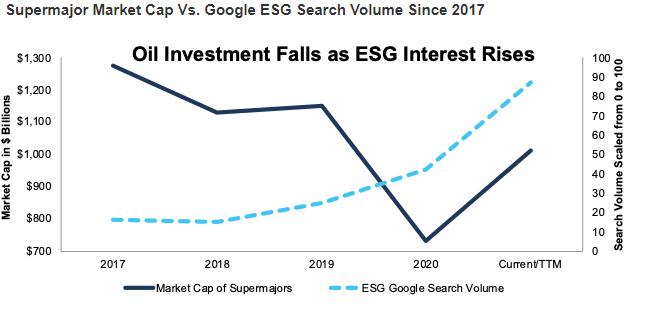

In addition, there has been, in the last decade, pressure applied by ESG investors for a great disinvestment from the industry. Last year, the Stichting Pensioenfonds ABP, the Netherlands’ pension fund for government employees, sold its positions in profitable energy companies, for ESG reasons. Activist investor, Engine No. 1, has worked to reduce the firm’s carbon footprint, since winning seats on the board last year.

While the Russo-Ukrainian War has forced Europe to invest in fossil fuel solutions in the interim, long-term, the path is away from fossil fuels. So what we have is a situation in which profitability is rising, but capital continues to exit, and will do so in future. Last year, New Constructs found that, while the core earnings of supermajors such as PetroChina (OTCPK:PCCYF) (PTR), China Petroleum (OTCPK:SNPTY, OTCPK:SNPMF)(SNP), Exxon Mobil (XOM), Chevron (CVX), Royal Dutch Shell (SHEL) (RDS.A), TotalEnergies (TTE), BP (BP), ConocoPhillips (COP), and Eni (E) fell just 1% between 2017 and 2021, their total market cap fell some 20%.

Source: New Constructs

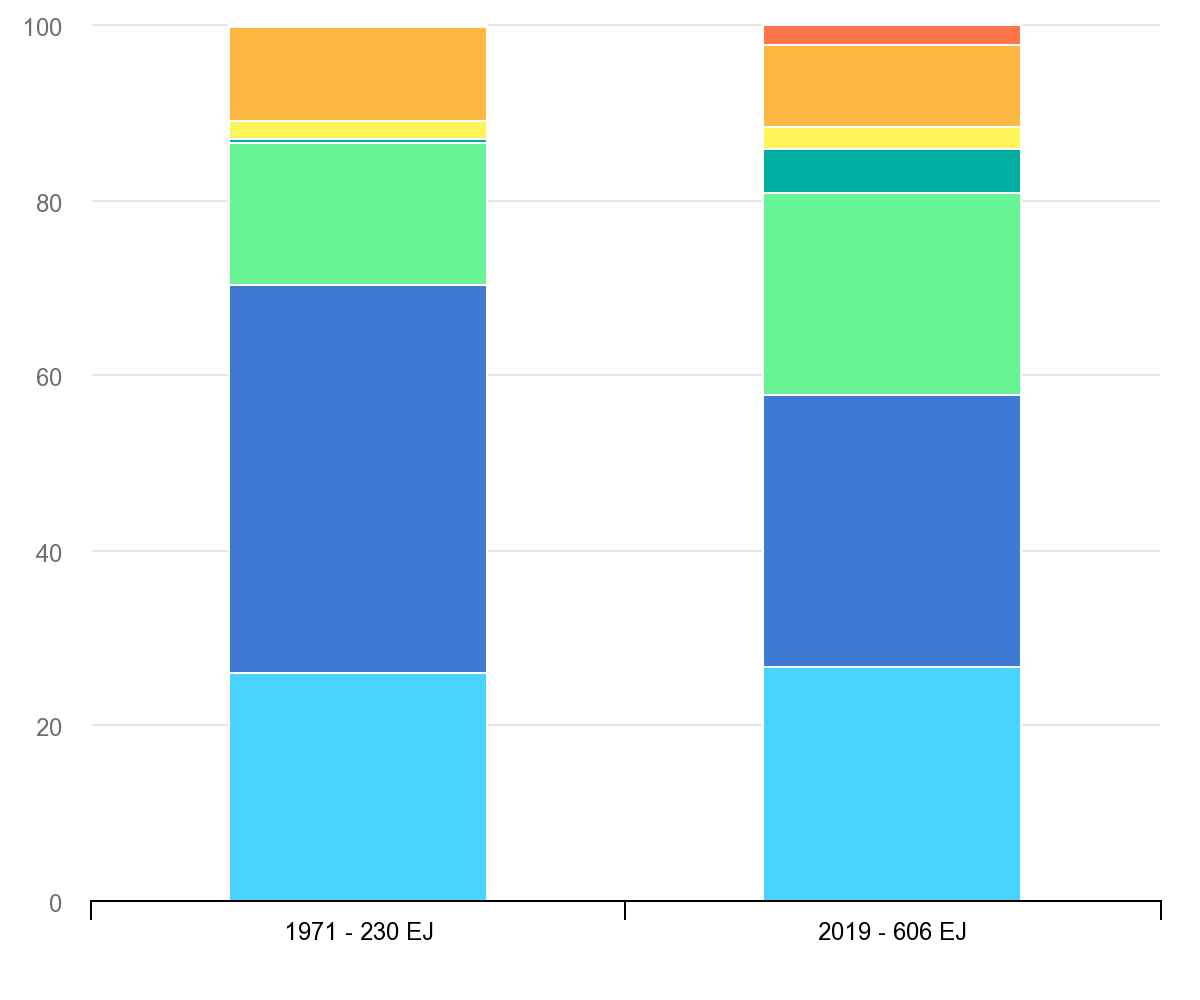

Driving the exit from fossil fuels is a belief that oil & gas are headed toward an Armageddon. However, as Cop 27 meets, it has become increasingly clear that the world will not be able to meet its 1.5C target for temperature rise, with the UN chief warning that the world is on the “highway to climate hell”. This failure has been driven by a misunderstanding of the pervasiveness and importance of oil & gas. Data from the International Energy Agency shows that oil made up 44.3% of the world’s primary energy supply in 2017, falling to 30.9% in 2019. While that is a large fall, spread out over several decades, it shows how the world is characterized by what Vaclav Smil has called “energy inertia” rather than the much touted rapid transition. Meanwhile, natural gas has grown from 16.2% in 2017, to 23.2% in 2019. That means, oil & gas has gone from 60.3% of the world’s primary energy in 2017, to 54.1% in 2019. Demand for oil 1 gas remains stubbornly high, despite decades of effort and a widespread narrative that the industry is on its last legs.

Source: International Energy Agency

Capital exits amidst energy inertia, and a growing sense of capital discipline within the industry means that profitability is sustainable. The industry is finally behaving in a rational manner. The United States’ reliance on the use of strategic reserves to dampen the price of oil, is a signal of the limited options the West has to reduce the price of oil. If demand rebounds, given the dearth of investment, prices will go higher.

Eni’s Solid Profitability

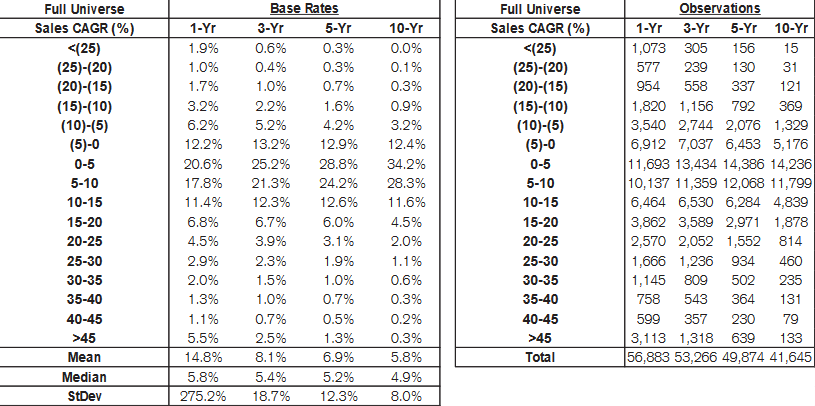

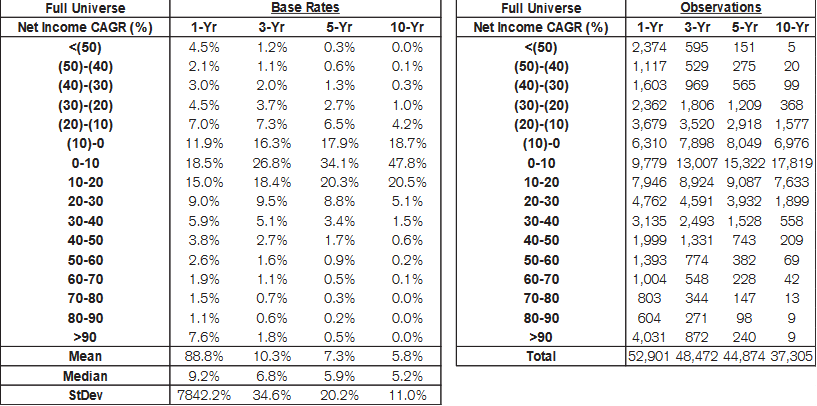

Eni’s own numbers reflect the industry-wide drift toward greater profitability. Between 2017 and 2021, revenue grew from $70.98 billion in 2017, to $77.77 billion in 2021. This gives us a measly 5-year revenue compound annual growth rate (or CAGR) of 1.85%. According to Credit Suisse’s The Base Rate Book, 28.8% of firms achieved a similar rate of growth between 1950 and 2015. In the nine months of the year, revenue grew to nearly $102 billion, compared to $50.693 billion for the same period last year.

Source: Credit Suisse

Eni’s gross profitability declined from 0.169 in 2017, to 0.16 in 2021, showing some deterioration in the attractiveness of the company, largely due to the asset growth in 2021. Gross profitability declined further in the nine months of 2022, to 0.155. This remains far below the 0.33 threshold that Robert Novy-Marx found made a stock attractive.

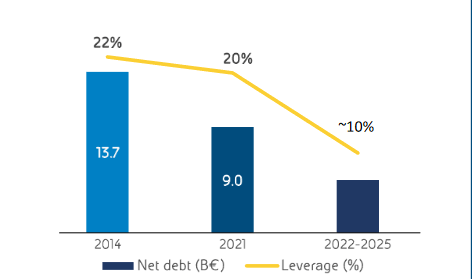

The company has made huge strides in improving its balance sheet strength, which is important, not just in terms of de-risking the business, but in order to better position the company from a capital cycle point of view, for future returns.

Source: Eni Investor Presentation; November 2022

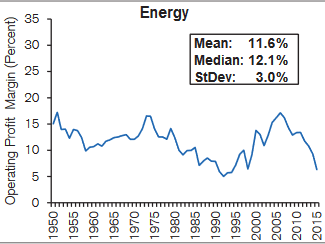

Operating margin rose from 11.3% in 2017, to 15.9%, hinting at improvements in value creation. According to The Base Rate Book, median operating margins for the energy sector, between 1950 and 2015, was 12.1%, while mean operating margins were 11.6%.

Source: Credit Suisse

Net income rose from $3.374 billion in 2017, to $5.821 billion in 2021, giving a 5-year net income CAGR of 11.52%. That gives us a base rate of 20.3% of companies. In the nine months of the year, net income rose to $13.26, compared to over $2.3 billion for the same period last year.

Source: Credit Suisse

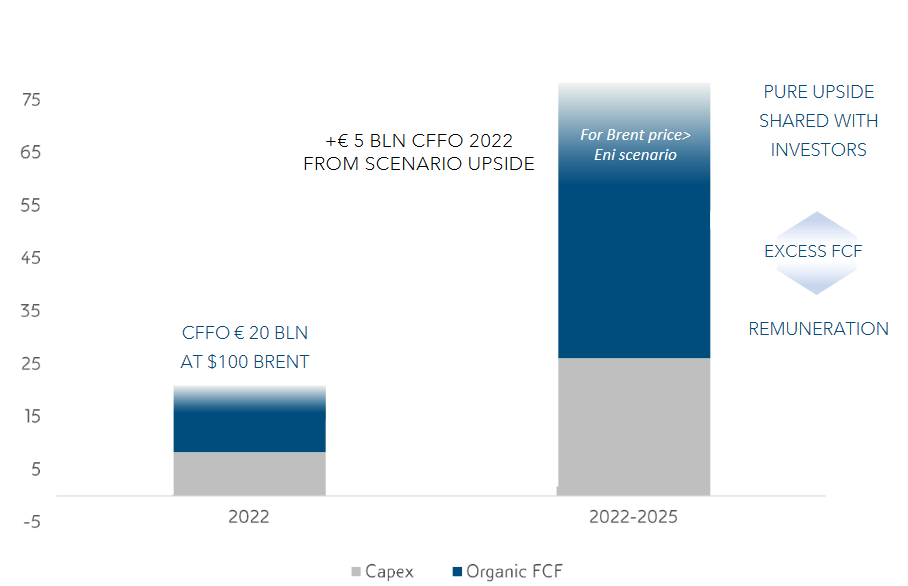

Eni grew free cash flow (or FCF) from €6 billion in 2017 to €7.6 billion in 2021. In the nine months of the year, FCF has already reached €7.438 billion. Eni believes that it will be able to increase cumulative 4-year FCF from €5.582 billion in 2021, to €25 billion for the 2022-2025 period.

Source: Eni Investor Presentation; November 2022

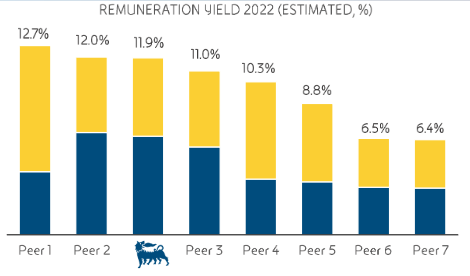

The company’s FCF has been used to remunerate Eni’s shareholders, at some of the highest remuneration yields in the industry.

Source: Eni Investor Presentation; November 2022

Eni’s return on invested capital (or ROIC) has declined from 11.6% in 2017 to 10.4% in 2021. Nevertheless, it remains top tier.

Valuation

Eni has a price-earnings multiple of 3.06, compared to 11.28 for the FTSE MIB and 20.01 for the S&P 500. In addition, the company has an FCF yield (FCF/enterprise value) of some 11.2%. This is in comparison with the mean FCF yield of 1.5% of the 2,000 largest companies in the United States, as measured by New Constructs. That suggests that future stock market performance will be superior to that of US markets.

Conclusion

While Eni’s numbers are not sensational, industry-wide trends lead us to believe that, as a rising tide lifts all boats, Eni will benefit from industry-wide trends and future profitability will grow sustainably. In addition, relative undervaluation should result in mean reversion and a rise in the share price. The company has been conservatively managed, and, given the likelihood of high long-term oil & gas prices, the odds of future profitability are very high.

Be the first to comment