tum3123/iStock via Getty Images

The “World Economic Outlook” report released by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) on April 19 depicted a worsening in the global economic scenario for 2022: lower economic growth and higher inflation than the January projections. As the Director-General Kristalina Georgieva said in the previous week, the war in Ukraine represented a “substantial setback” for the global economic recovery.

Emerging market and developing economies (EMDE) face a common set of external shocks: rising energy and food prices; tightening in global financial conditions caused by the prospect of sharper interest rate hikes and anticipation of “quantitative tightening”; and return of restrictions on mobility in China, on account of the Covid zero policy, leading to slumping in growth and weakening one of the primary growth drivers for the other EMDE. However, the impacts of those common shocks on EMDE have been heterogeneous.

Global inflation and growth deceleration

The IMF pinned the global slowdown on Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. It projected a sharp decline in 2022 economic growth as the war drives up energy prices and stumbles on pandemic economic recoveries. The IMF forecasts global growth at 3.6% for the year, lower than its 4.4% forecast issued in January. Beyond 2023, it expects growth to slide down to about 3.3%, whereas growth in 2021 was about 6.1% (IMF, 2022).

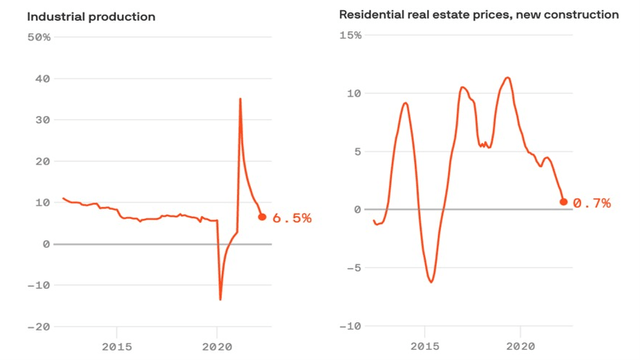

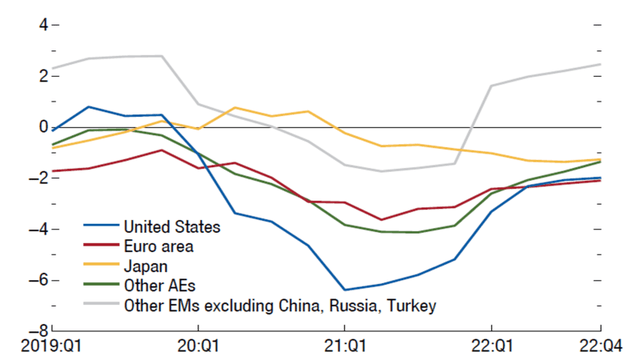

Figure 1 depicts the reviewed paths forecast by the IMF for potential GDP starting in October 2019.

Figure 1 – Potential GDP (Index, 2019 = 100)

Note: Potential real GDP projections indexed to 2019 values. Each line reflects a different vintage of World Economic Outlook (WEO) projections. AEs = advanced economies; EMDEs = emerging market and developing economies.

The analysis pairs that of the World Bank, which slashed its global growth forecasts from 4.1% to 3.2% the previous day. One must consider that the IMF uses Purchasing-Parity-Parity-adjusted exchange rates in adding GDPs, while World Bank uses nominal exchange rates. Therefore, the weight of non-advanced countries tends to be higher in the IMF’s global growth figures.

The post-pandemic global economic recovery was already slowing when the Russian invasion of Ukraine triggered new commodity price shocks, at the same time causing a new wave of restrictions in supply chains (Canuto, 2022).

The IMF also points out the effects of monetary tightening and financial market volatility. Before the war, inflation rose significantly, and many central banks started tightening monetary policy. This contributed to a rapid increase in nominal interest rates across advanced economy sovereign borrowers. Policy rates are expected to rise in the months ahead record-high central bank balance sheets will begin to unwind, most notably in advanced economies.

Figure 2 shows the WEO forecasts for basic real interest rates in advanced economies and emerging market economies.

Figure 2 – Real policy rates (percent)

Note: Euro area’s projection part is estimated by using 16 individual euro area countries’ projections. Other AEs and other EMs comprise 12 and 10 economies, respectively. AEs = advanced economies; EMs = emerging markets.

The expectation of tighter monetary policies follows the upward review of inflation forecasts. With the impact of the war in Ukraine and the broadening of price pressures, inflation is expected to remain elevated for longer than previously forecast. The conflict is likely to have a protracted impact on commodity prices, affecting oil and gas prices more severely in 2022 and food prices well into 2023 (because of the lagged impact from the harvest in 2022). Even with the anticipated increases in policy rates, given the outlook for inflation, short-term real interest rates at the end of 2022 are likely to be still negative. How high will they have to go is a wide-open question.

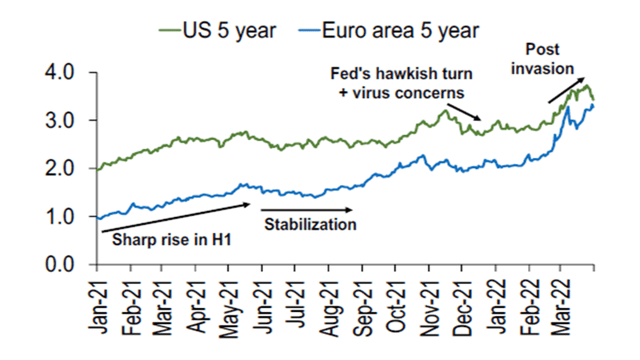

The dilemma faced by central bankers between accepting inflation or slowing demand was made worse by the shocks triggered by the war. .S. Inflation expectations have gone up on both U.S. and European sides of the Atlantic, as measured by corresponding breakeven 5-year interest rates (Figure 3). In March, U.S. inflation reached 8.5%, its highest annualized level in 40 years.

Figure 3 – Inflation expectations increasing (Inflation breakeven, percent)

Chapter 2 of the IMF (2022a) calls attention to how the recent record rise in private debt could affect economic recovery, even if the drag on growth tends to vary across countries and within them.

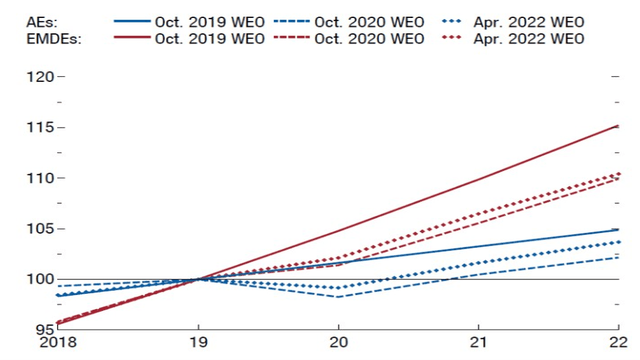

Meanwhile, China’s ‘zero-COVID’ policy has also brought supply shocks and supply chain disruptions. Chinese economic data out on April 18 revealed that its economy has felt the impact as the government aggressively fights the worst outbreak of COVID so far on the mainland. Industrial production decelerated sharply in March, as did investment in the domestic real estate sector, a key driver of the country’s growth (Figure 4). As it remains an export giant and a crucial cog in global supply chains, Chinese factory shutdowns and logistical disruptions will amplify global supply-chain disruptions and price pressures.

Figure 4 – China: industrial production and new construction

Axios (2022). 1 big thing: China’s economy is sputtering, April 19.

Rising financial stability risks

The Global Financial Stability Report, also released by the IMF on April 19 addresses another dilemma: accepting inflation or risks of financial instability arising from sharp rises in interest rates. Important detail: the two dilemmas intersect. In the case of the United States, many analysts believe the Fed is late on its rate adjustment route. If it finds itself forced into steeper rises ahead, the bumps on high-leverage private corporate structures will be substantial.

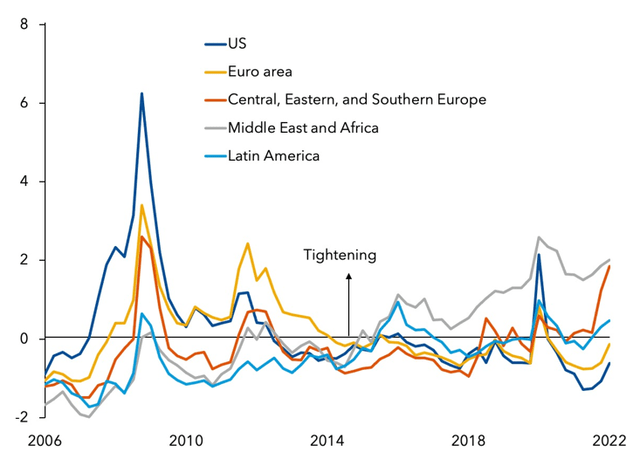

Since the beginning of the year, financial conditions have tightened significantly across most of the world, particularly in Eastern Europe (Figure 5). Given rising inflation, the interest-rate evolution that we saw in Figure 2 has led to a tightening in advanced economies in the weeks following the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Even with that tightening, financial conditions are close to historical averages, and real rates remain accommodative in most countries.

Tighter financial conditions help to slow demand and prevent a loss of anchoring of inflation expectations and, therefore, the anticipation of continued price increases in the future becoming the norm. Many central banks may have to move further and faster than what is currently priced in markets to contain inflation. This could bring policy rates above neutral levels (a “neutral level is one at which monetary policy is neither accommodative nor restrictive and is consistent with the economy maintaining full employment and stable inflation). This is likely to lead to even tighter global financial conditions.

Figure 5 – Financial conditions

Emerging economies: common factors, but differentiated impacts

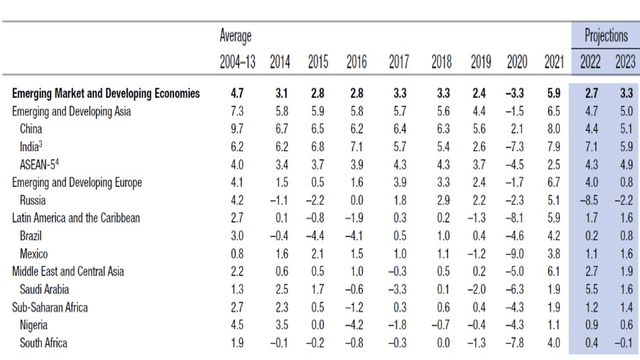

IMF also downgraded the forecast for the emerging market and developing Economies (EMDE) cluster compared to January projections. In this case, however, with much more significant heterogeneity. From the inflationary spike, on the other hand, no one escapes, bringing with it pressure to raise interest rates.

Table 1 – EMDE real per capita output

(Annual percent change; in constant 2017 international dollars at purchasing power parity)

Expectations of tighter policy in advanced economies and concerns about the war have contributed to financial market volatility and risk repricing for EMDE. In EMDE, several central banks have recently tightened monetary policies, adding to those already started to do so in 2021. One exception is China, where inflation remains low, and the central bank cut policy rates in January 2022 to support the recovery.

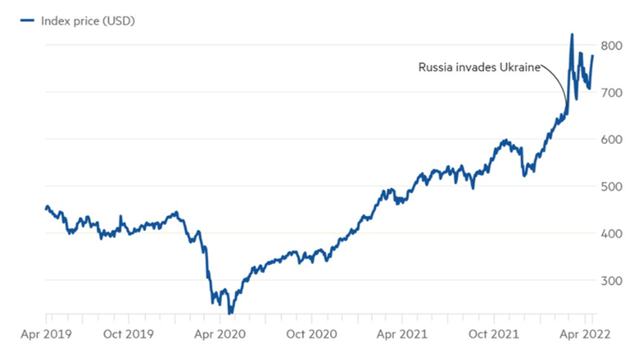

EMDEs face a common set of external shocks: rising energy and food prices, aggravated by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine (Figure 6); tightening in global financial conditions caused by the prospect of sharper interest rate hikes and anticipation of “quantitative tightening” (as we saw in Figure 5); and return of restrictions on mobility in China, on account of the Covid zero policy, leading to slumping in growth and weakening one of the primary growth drivers for EMDE (Figure 4 above). Fiscal stimulus in China points in the opposite direction, but there are doubts about the sustainability of this policy.

Figure 6 – Commodity prices: dollar price of S&P GSCI global commodity market index

Financial Times, Sandbu (2022)

However, the impacts of common shocks have been heterogeneous. Four subgroups can be distinguished among EMDE.

First, of course, Ukraine suffered the destruction of the war, Russia under sanctions, and the other economies in the region integrated. In addition to higher inflation, Russia will experience a recession worse than the 1998 crisis and the global financial crisis in 2008, albeit, paradoxically, with the highest current account surplus in the last 20 years.

In Russia, the sanctions and the impairment of domestic financial intermediation have led to large increases in its sovereign and credit default swap spreads. Emerging market economies in the region and Caucasus, Central Asia, and North Africa have also seen their sovereign spreads widen. The IMF forecasts GDP declines in Russia of 8.5% and 2.2%, respectively, in 2022 and 2023 (Table 1).

The second group of EMDE is comprised of commodity exporters (excluding Russia), which are benefiting from more favorable terms of trade. While this is not enough to fully protect them, strengthened public revenues provide fiscal leeway for measures to smooth the rise in domestic energy prices. Larger current account balances will also cushion the effect of tightening global financial conditions. Countries that are more advanced in the monetary tightening cycle, such as Brazil, benefit from their currencies’ appreciation. Commodity exporters – excluding Russia – were the only group of countries for which the IMF lifted its growth prospects for 2022 compared to January projections.

Nonetheless, the inflation challenge has also risen for them. Because of the pandemic and the war in Ukraine, the inflation rate in Latin America’s largest economies – Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Mexico, and Peru – has been the highest inflation in 15 years (Appendino, et al, 2022). The weight of import and commodity prices on Latin American inflation is greater than that of advanced economies.

A third group corresponds to commodity importers, for whom manufacturing exports weigh, that are suffering both the impact of higher energy and food prices and the slowdown in global growth. Slower growth, higher inflation, deteriorating public accounts, and lower current account balances are forecast.

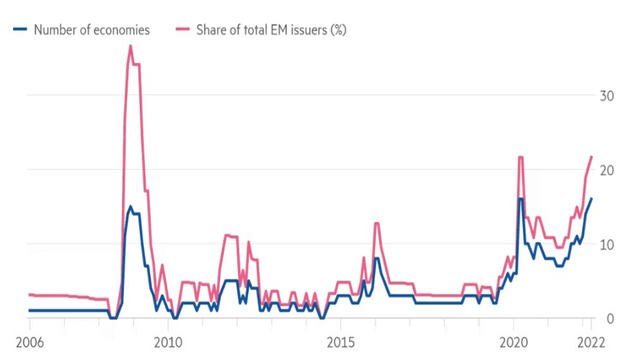

The fourth subgroup is developing economies grappling with the indebtedness inherited from the pandemic. Higher debt and less favorable global financial conditions make it difficult to roll over external debt services and finance current account deficits. Here, the volume of the current call by multilateral institutions -World Bank and IMF-to consider the possibility of debt restructuring processes with external creditors will get even louder.

A wave of EMDE debt crises seems to be coming, remarks Estevão (2022), from the World Bank:

“On the eve of the war, many of them were already on shaky ground. Following up on a decade of rising debt, the COVID-19 crisis expanded total indebtedness to a 50-year high-the equivalent of more than 250 percent of government revenues. Close to 60 percent of the poorest countries were already in debt distress or at high risk of it. (…) The Ukraine war immediately darkened the outlook for many developing countries that are major commodity importers or highly dependent on tourism or remittances. (…) Over the next 12 months, as many as a dozen developing economies could prove unable to service their debt.

Levels of distress are at risk of rising much higher if central banks in advanced economies feel compelled to move too abruptly or aggressively to unwind the monetary policy stimulus injected since the pandemic as a reaction to the inflation surge forecast by the IMF.

Figure 7 – Distressed EMDE hard-currency sovereign issuers

Financial Times, IMF; Smith and Platt (2022)

Note: distressed: spreads over US Treasuries above 1,000 basis points

Bottom line

The war in Ukraine and China’s growth deceleration have brought a common set of external shocks for EMDE. Besides rising energy and food prices and tightening in global financial conditions caused by the prospect of sharper interest rate hikes and anticipation of “quantitative tightening”, the return of restrictions on mobility in China, on account of the Covid zero policy.

The impacts of those common shocks on EMDE have been heterogeneous, with some commodity exporters even slightly improving GDP performance. What is undeniable is that the growth prospects and the terms of the policy trade-off between economic activity and inflation have deteriorated, besides looming risks associated with tightening global financial conditions. At the same time, economies under debt distress will face an even more challenging environment.

Be the first to comment