Ryan Fletcher/iStock Editorial via Getty Images

While Boeing (NYSE:BA) was trying to solve its problems on the Boeing 737 MAX, the company was hit by a new crisis. This time the Boeing 787 was the centerpiece of negative attention. In various reports, I have discussed the problems that Boeing faced and resulted in a delivery stop for Boeing’s newest jet. In this article, I provide an update as deliveries are resuming and provide insights on the value of the jets currently held in inventory.

Why I’m Providing An Update On The Boeing 787 Situation

Before I turn my attention to the financial side of a delivery resumption, I want to briefly address what has changed over time. When the first issues were detected, I asked Boeing whether they had additional information for me on the timeline for the fixes. My simple question was whether this would be a matter of days, weeks or months to be solved. I did not receive any timeline information, but we are now over 20 months later. I think we got our answer.

The sliding timeline in part is also the result of intensified scrutiny from the FAA as the FAA has shown extremely bad figure throughout the Boeing 737 MAX crisis. However, what was extremely unsettling is that Boeing’s communications in my view have remained largely opaque. So, when I asked in September 2020 about information, I didn’t receive anything that was truly insightful on the timeline element and that became a problem as I was dealing with addressing the risk of cost growth on the program.

In January 2021, I warned investors for a potential write off on the program and that did happen in the fourth quarter of 2021 as Boeing took a $3.5 billion charge on the Dreamliner program. The company, with reason, was mute on providing a timeline but airline delivery schedules sliding and industry insights suggested that resumption timelines were missed in October 2021 as well as April 2022. This sparked a concern with me that Boeing would be recognizing additional cost growth in their Q1 2022 earnings. This, however, did not happen as I discussed in the analysis of Boeing’s Q1 2022 earnings. That provides part of the positives and is why I’m providing an update on the situation. So, Boeing did not see cost growing further and it suggests that the airplane maker had de-risked beyond an April 2022 delivery resumption.

Additionally, Boeing shared during its Q1 2022 that it had filed a plan with the FAA that would allow the jet maker to continue deliveries. The catch, however, was that Boeing submitted the plan very briefly before earnings were published and that suggests that the plan was submitted in order to be able to tell investors there was progress. Days later, the FAA shared with Boeing that its certification plan was incomplete.

It’s not known whether the review of the certification plan has been completed, but a release from Lufthansa suggests that Boeing is closing in on a delivery resumption and this is further supported by statements from Boeing Commercial Airplanes CEO Stan Deal that the company is almost there.

While I believe that the risk of cost growth persists as there’s no timeline provided for Boeing’s assumption on the time variable for the financial de-risk, there have been positive moments since the last time I addressed the Boeing 787 crisis:

- No further cost growth occurred in the first quarter of 2022.

- Airlines are preparing to take delivery of their Dreamliners.

- Conforming aircraft are now being produced.

At the same time, with an open-ended timeline there’s still no certainty or sense of robustness in the progress.

Dreamliner: A Big Financial Load

The Dreamliner provides a big financial load on Boeing with $13.5 billion in profits that were recognized upfront but have not yet materialized and actually might not materialize. However, what I want to pay closer attention to is the value of the aircraft that ended up in Boeing’s inventory during the delivery stop.

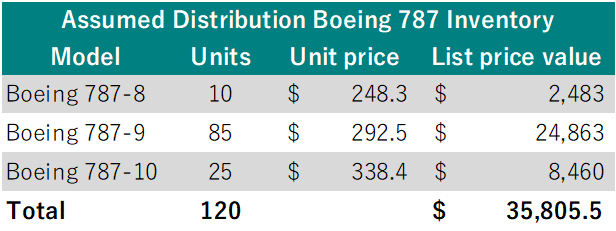

The Boeing 787 family consist of three models, the -8 through -10, and we don’t know the exact distribution between those models in inventory. However, from Boeing’s filings we do know that there were 115 Dreamliner aircraft in inventory at the end of the first quarter, up 5 units from the start of the quarter. So, by now there should be 120 Boeing 787s in inventory. How big the inventory is should also become clear when we consider the pre-pandemic delivery levels of 158 units in 2019 and 114 units in 2014 when Boeing made a big step up production on the Dreamliner program.

Boeing 787 inventories (The Aerospace Forum)

Using the 120 aircraft in inventory, we start our calculations where we assume a distribution between the three models similar to the mix in 2019. Using list price values, the inventory would be valued $35.8 billion. However, by now most people know that aircraft are always sold at significant discounts. Keeping the current market value and base market value in mind, the Boeing 787 inventory still represents $16.4 billion to $17.6 billion in revenues.

To give you an impression of how big this number is:

- Boeing’s first quarter revenue was $13.9 billion.

- Boeing Commercial Airplanes revenues was $19.5 billion last year.

- Boeing Commercial Airplanes revenues in an undisturbed market are around $60 billion.

So, even compared to a good year the inventory would be worth around 25 to 30 percent in terms of revenues. That’s a huge amount, and it also represents 120 aircraft for which Boeing did not receive final delivery payments. Following typical pre-delivery payment patterns, this would result in an estimated $5.6 billion to $6.9 billion due on delivery. So, there’s a big chunk of cash flow that will enabled once deliveries can recommence and the delivery resumptions will mark the start of an estimated $13 billion in reduction of inventories. Again, to provide some context: By the end of the first quarter Boeing’s inventory levels were $80 billion. The normal cost levels of the produced aircraft represents over 15% of the inventories. So, a delivery resumption will allow for a deflation of inventories.

What should be kept in mind is that the final delivery payments are not necessarily a pass-through to the free cash flow, or in other words, you will not see Boeing 787 free cash flow jump by $5 billion to $7 billion once all aircraft are delivered.

There are two reasons for that, the first one is that there are abnormal costs that Boeing will largely incur this year and next year and there are customer compensations involved as Boeing explained when it recognized the $3.46 billion charge:

Additionally, we recorded a $3.5 billion noncash charge in the quarter to write down unamortized deferred production costs, primarily due to estimated customer compensation for the longer delivery delays. It is important to keep in mind that from an economic standpoint, cash margins on the 787 remain positive. While the additional costs and customer considerations will put some downward pressure on cash margins in the near term, cash margins are expected to remain positive and significantly improve over time.

So, while Boeing took a non-cash charge, there will be pressure on the cash margins which is not odd since the hit to earnings has already been recognized but the translation to pressure on cash margins happens on a case-by-case basis. We also know from the Boeing 737 MAX liabilities, most of the compensation happened in the form of cash compensation made to customers and reduced delivery payments. So, most of it will likely be cash pressures if the Boeing 737 MAX liabilities reduction serves as a template for the reduction in Boeing 787 liabilities. Unfortunately, Boeing does not provide a breakdown of customer compensations for the jets and the $3.5 billion does not solely consist of cash pressures or compensation for that matter.

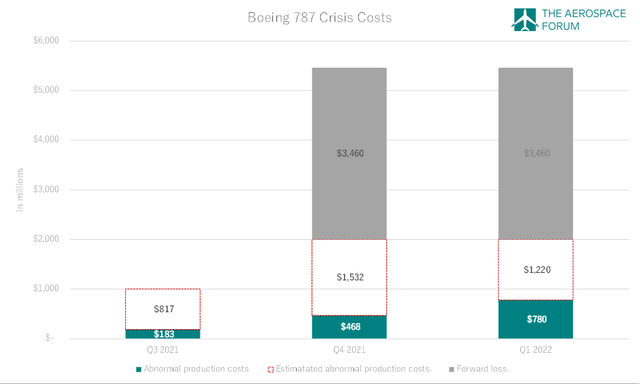

A combination of accumulated abnormal production costs and charges shows us the following:

Boeing 787 cost accumulation (The Aerospace Forum)

In total, Boeing expects to incur $2 billion in abnormal production costs of which $780 million has already been incurred and the remainder will mostly be recognized by the end of 2023. In total, the current estimate of the Boeing 787 costs is $5.46 billion. Interesting to note is that this number is similar to the $5.6 billion that I estimated as the lower-range number for final delivery payments. While cash (final delivery payment) and costs ($5.46 billion) are not the same since not all costs are cash costs, I do believe that Boeing will see a significant portion of its final delivery payments flow out in the form of compensation rendered to customers or that cash simply will not come in since a final delivery payment will not occur when the aircraft is handed over to customers.

What should also be noted is that $780 million out of the $2 billion in abnormal production costs has already been recognized, and out of the $3.5 billion charge, an unidentified amount might already have resulted in customer compensation being rendered. So, assuming that most of the costs and compensation will be on a cash basis, there will be $5.6 billion to $6.9 billion due in delivery payments and I estimate that by Q2 2022 without any changes on the abnormal production costs estimate, the rendered abnormal production costs will be around $1 billion to $ 1.1 billion.

If we make a quick calculation, the total delivery payments minus the cost compensation would be $0.1 billion to $1.5 billion. That means that the current inventory of undelivered aircraft could in the worst case just be an inventory built that will serve as a way to render customer compensation and not so much as an addition to Boeing’s cash pile. However, around $1.1 billion and an unidentified balance of the $3.5 billion charge might already have affected cash flow which would bring the possible net cash contribution once deliveries start to $1.2 billion to $1.6 billion. Measured from the moment deliveries restart, the inventory of Dreamliner aircraft could in fact be accretive to Boeing’s cash flow. With that in mind, the Boeing 787 delivery resumption is just not a symbolic milestone but also one that could help Boeing improve its cash flow and subsequently its debt levels.

Things to Consider

While this story is positive, I do think that investors should take note of some things. The first thing is that while there might be up to $7 billion due in final delivery payments, one should not expect a sudden jump in free cash flow. The inventory unwind will take time. There will be an initial ramp up in unwinding and it is expected that the unwind will be completed in 2024, that is also the timeframe on which you should see things improve but on a quarterly basis you will not see major jumps even though the inventory unwind is happening. Furthermore, part of the delivery payments will be offset by abnormal production costs and customer compensations.

Additionally, the calculations in this report are best estimates based on what Boeing has provided. The ability to calculate the cash flow pressure is limited by the lack of insight in cash costs as well as progress in customer compensations and how much of the $3.5 billion charge of the non-cash charge will ultimately result in cash flow reductions. So, some detail is lost due to the lack of insight in cash- and non-cash items. However, our estimates do assume that all costs are in cash form and as a result provide the worst-case scenario on the cash flow and even then, we see value in the inventory based on current charges and abnormal production costs.

For profit margins, one should keep in mind that delivery resumption of the Boeing 787 will not result in improvement in the margins as Boeing will be recognizing a breakeven margin on the Boeing 787 program. So, the revenue will increase and so might the cash flow, but there will be no profit booked on the Boeing 787 deliveries which will provide a damper on Boeing Commercial Airplanes margins. Investors should be aware that this is exactly how program accounting works to compensate for earlier recognized profits being too high, or said differently: Boeing already booked the profits on the 0-margin aircraft in earlier years. A reduction in profit margin is also not an indication of reduction in cash margins and those cash margins are still strong for the Boeing 787 program.

Another positive is that the delivery resumption likely also will mean that Boeing will increase its production rate. By 2024, it’s expected that international air travel will have recovered and so we also expect healthier demand levels for wide body aircraft. So, Boeing could start raising rates in response to that improving demand environment and improve the already strong cash margins on the Dreamliner program.

Conclusion

In this article, I drilled down from list price value all the way to worst-case scenario estimates on cash flow from the inventory unwind. These calculations showed that the Boeing 787 inventory unwind should be a cash positive story for Boeing. Since these are worst-case scenario using the current projections, the actual cash story could even be materially better. Investors should, however, be aware that while the cash margins are strong, program accounting will require a zero profit to be booked on deliveries. Additionally, the inventory unwind will not happen overnight and is expected to take several years. That means that one shouldn’t be expecting jumps in the billions of dollars in cash flow on sequential basis. I believe that with the inventory unwind and improving production rates once deliveries recommence, things will be looking a lot better for Boeing.

Be the first to comment