DNY59/E+ via Getty Images

The top reason for owning an index fund

Creative destruction. It’s an inescapable consequence of capitalism and one of the top reasons (if not THE top reason) to own an index fund. For example, Standard and Poor’s keeps the Dow Jones Industrial Average relevant by occasionally pruning away the outdated and struggling companies and replacing them with newer, more promising companies. Like back in 1999, when Standard and Poor’s removed the (now bankrupt) Sears Roebuck & Company from the Dow Jones and replaced it with the (thriving and highly profitable) Home Depot (HD). Or how about in 1997 when Hewlett Packard (HPE) replaced erstwhile Dow Jones component Bethlehem Steel (a now-defunct company). The economy changes, and the Dow Jones keeps pace by periodically hitting the “refresh” button. Doesn’t that strike you as a sensible thing to do? It certainly strikes me that way.

So let me ask you this. Knowing everything that you know today, imagine that you travelled back in time to 1985 to advise an investor who faces a choice. Option one: she buys a mutual fund that tracks the Dow Jones Industrial Average and then holds that fund and reinvests her dividends until today. (Since there aren’t any mutual funds today that tracked the Dow Jones Industrial Average in 1985, we’ll use the Vanguard 500 Index fund as a proxy.)

Option two: the investor buys seventeen of the top individual components of the Dow Jones Industrial Average (including three that you know ahead of time will ultimately go bankrupt). She then holds those stocks until today, reinvesting dividends but never adding any of the new stocks that have come into the Dow Jones Industrial Average since 1985.

Which strategy would you advise her pick; the index fund, or the static portfolio of single stocks from 1985?

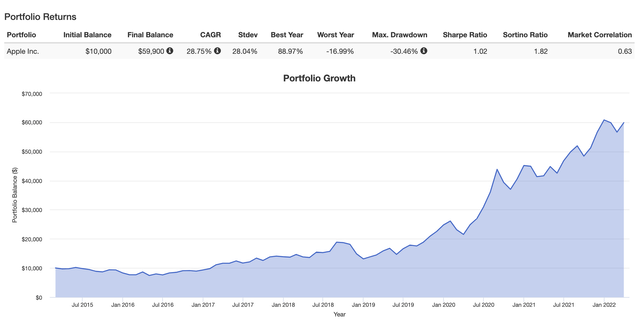

Before you answer, allow me to highlight some of the shares this investor would own today if she picked the static portfolio back in 1985. She would own stocks of trendy, cutting-edge businesses like Goodyear Tire & Rubber Company (GT), International Business Machines (IBM), General Electric (GE) and International Paper (IP). She would be nursing 100% losses on three of her 17 original investments – Sears, General Motors (GM) (pre-2009 bankruptcy) and Bethlehem Steel have all gone belly up. Oh, and to her dismay, she would have completely missed out on the stunning performance of some of the more recent additions to the Dow Jones Industrial Average. For example, unlike the index fund investor, she’d have zero exposure to Apple (AAPL) which is now up 6,000% from the time it was added to the Dow Jones in March of 2015 according to Portfoliovisualizer.com (assuming dividends are reinvested into more (AAPL) shares).

Apple’s performance since joining the Dow Jones (Portfoliovisualizer.com)

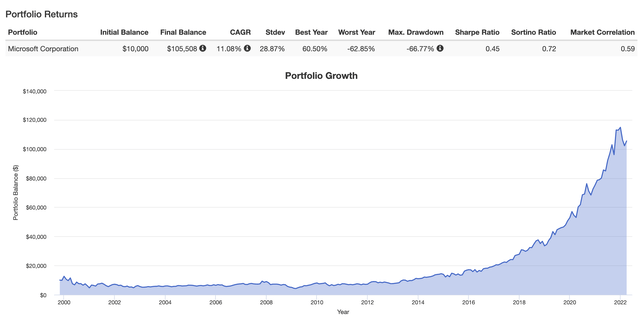

She would have zero exposure to Microsoft (MSFT), which was added to the Dow Jones on November 1, 1999 and is now up over 10,000% since that time according to Portfoliovisualizer.com (dividends reinvested).

Microsoft performance since joining the Dow Jones (Portfoliovisualizer.com)

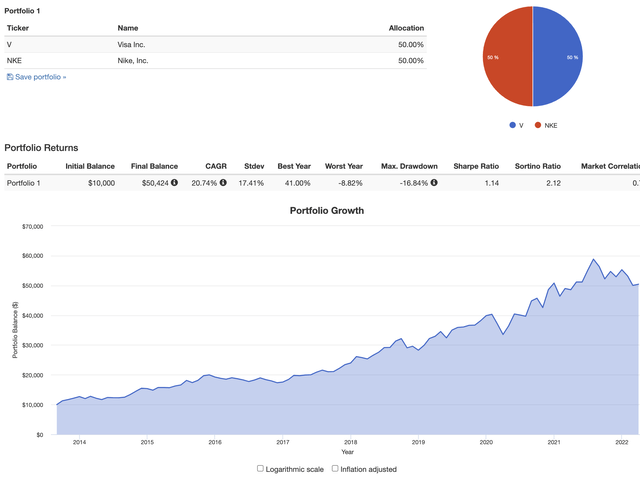

Nor would she have any exposure to Nike (NKE) and Visa (V), which joined the Dow Jones Industrial Average in September of 2013 and which, just nine years later, would be up over 5,000% combined.

Visa and Nike performance since joining the Dow Jones (Portfoliovisualizer.com)

Armed with this little historical refresher, it seems obvious that you’d advise the investor in 1985 to pick the index fund over the static portfolio of individual stocks. Wouldn’t you rather that she have exposure to those new, innovative and explosively profitable companies that were added to the Dow Jones after 1985, while at the same time avoiding all those companies that became stale, less relevant, or even insolvent? I know that recommending the index fund would have been my choice.

And as so often happens with my investment choices, it turns out that I would have been wrong.

A static portfolio from 1985

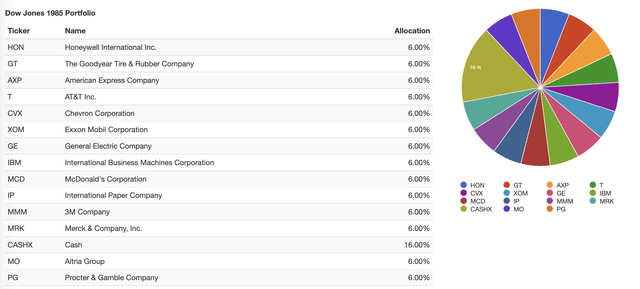

Background: the Portfolio Visualizer tool doesn’t include data on all of the components of the Dow Jones Industrial Average from 1985. For example, the tool only tracks the stock performance for United States Steel (X) from 1991, and only tracks Alcoa (AA) from 2016. Another challenge is that many of the original Dow Jones companies in 1985 went through substantial reorganizations, privatizations, mergers and spin-offs – Dow Chemical, DuPont (DD), Eastman Chemical (EMN), Woolworth’s – making it difficult or impossible to track the performance of today’s surviving corporations back to their 1985 predecessors. So I imagined a starting portfolio of $10,000 back in 1985 with 6% allocations to each of the 14 Dow Jones Industrial components that still trade today in more or less the same form as they did in 1985 (with the exception of Altria, after having verified that Portfolio Visualizer accurately incorporates data from Altria’s spin-off of Philip Morris International (PM)).

I also assumed that my hypothetical investor in 1985 would have invested a total of 16% of her initial portfolio into Sears, General Motors (pre-bankruptcy) and Bethlehem Steel. I did so because it’s relatively straightforward to account for the 100% loss that she would have ultimately taken on those investments. To simulate the portfolio impact of those bankruptcies, I allocate 16% of the original portfolio to a cash position that I will subtract out at the end.

Here is a snapshot of the portfolio constituents:

Index constituents (Portfoliovisualizer.com)

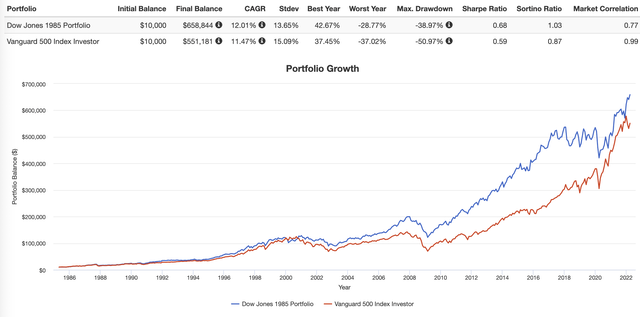

Result: Here is how the static portfolio of Dow Jones Industrial Average stocks would have performed from 1985 to today compared to an investment in the S&P 500 over the same time period. I assume no rebalancing for the static portfolio and continuous dividend reinvestment for both the S&P 500 fund and the 1985 static portfolio.

Static 1985 Stock Performance (Portfoliovisualizer.com)

When we subtract the original $1,600 that would have been lost to our unlucky investments in Sears, General Motors and Bethlehem Steel, our ending balance for the 1985 static portfolio would equal $657,244 compared to $551,181 for the Vanguard S&P 500 index. In other words, over the past 37 years, the static stock portfolio ends up outperforming the S&P 500 by over 19%.

Stop and consider this result for a moment. A portfolio comprised of companies like Goodyear, International Paper, General Electric and AT&T outperforming a portfolio that contains hefty allocations to Apple, Goldman Sachs, Visa, Nike. How can that even be possible?!?!?!

Lessons learned

Whenever you stumble across a counterintuitive fact, that’s often just life’s little way of subtly waving a bright red flag right in your face and screaming “hey! there’s something to learn from all this!” The trick is in deciphering that lesson, which often comes down to asking the most obvious question that you can possibly think of. In this case, the most obvious question is: how and why does a static portfolio of stodgy (and in some cases, bankrupted) companies outperform a dynamic, up-to-date index that includes the most innovative and successful companies of our time?

And as is so often the case with life, the simplest explanation may come down to just one simple rule. In this case, the rule seems to be this: it’s bad to interrupt the power of compounding for virtually any reason.

Index providers (like portfolio managers everywhere) add and subtract stocks from their portfolios for reasons that often make extremely good sense at the time (and that might even seem brilliant or prescient in retrospect). The problem is that each time they do that, then for better or for worse they must necessarily interfere with the power of compounding. I hypothesize that the secret behind why and how the static 1985 portfolio outperforms the broader, continuously-updated index is that the static investor never lifts her finger for any reason besides reinvesting dividends (which augments rather than interferes with the power of compounding).

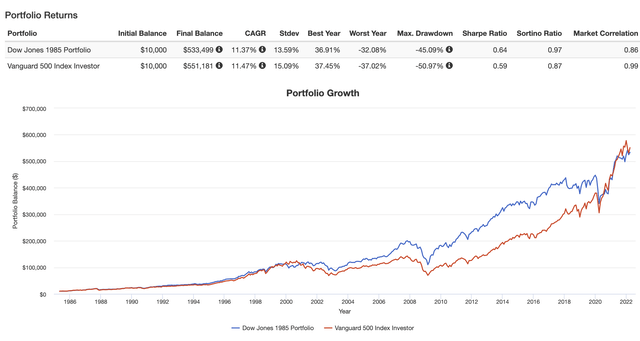

To test my hypothesis, I ran the exact same analysis of the 17 Dow Jones Industrial companies from 1985 except this time, I assumed the portfolio is rebalanced on a monthly basis (which is to say, monthly interruptions of the power of compounding). Low and behold, the now-less-static portfolio underperforms the S&P 500 by a fraction of a percent.

Performance of Rebalanced portfolio (Portfoliovisualizer.com)

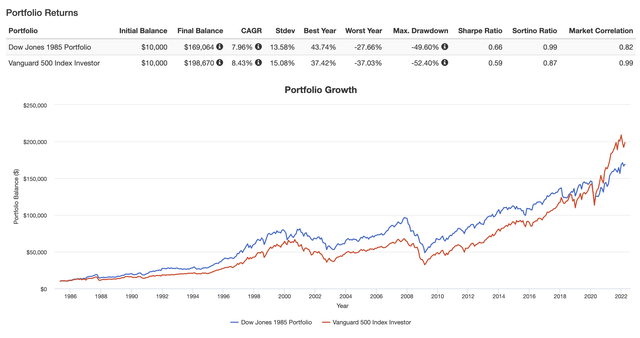

Next, I ran the exact same analysis except this time, I assumed no rebalancing and also assumed that no dividends would ever be reinvested. According to Portfolio Visualizer, the static portfolio now underperforms the S&P 500 portfolio by a little less than 1% per year on average. Demonstrably, the power of compounding is a crucial ingredient when it comes to either outperforming or underperforming the broader index. We should have expected as much from this result, but it’s good to verify since we know that when it comes to the stock market, expectations and reality don’t always mesh.

Performance of non-reinvested portfolios (Portfoliovisualizer.com)

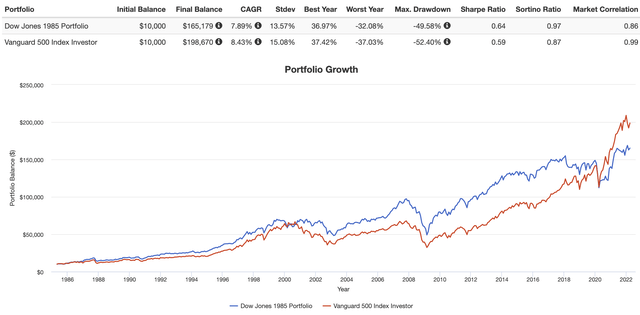

Finally, I ran the exact same analysis except this time, I assumed both monthly rebalancing and zero reinvestment of dividends. The static 1985 Dow Jones portfolio underperforms the S&P 500 by a bit less than 1% per year.

No reinvestment, no rebalancing (Portfoliovisualizer.com)

So the hypothesis seems correct. Reinvesting dividends and avoiding any other action whatsoever is the key to why the static Dow Jones Industrial portfolio from 1985 outperforms the broader, continually-updated S&P 500. There may be other factors at play too (overpaying for new index constituents, for example). However, you want to slice it, the key to delivering more seems to be doing less.

You may have your own conclusions about what lessons to take from the experiment (which I invite you to add in the comments section), but here are mine:

(1) You do not need to invest in the most successful and innovative companies in order to generate market-beating returns.

(2) To beat the index, you do not need to avoid investing in companies that ultimately go bankrupt. Nor do you need to worry about picking stocks that ultimately go stale or out of favor – indeed, six of our original Dow Jones Industrial picks ended up getting unceremoniously kicked out of the index during our holding period.

(3) To generate market-beating returns, a steady habit of buy, hold, and reinvest can be perfectly sufficient.

(4) What seems like it should be a tremendous value-added service of index fund investing – removing old companies and replacing them with new companies – turns out to be less valuable than most of us (including your author) would have ever guessed. In fact, as this example shows, adding or subtracting any companies from the portfolio could possibly even be counterproductive as far as maximizing returns goes.

Compound. Do nothing but.

A quick dedication to someone I love

I’m dyslexic, but certainly not for want of things to say. Since reading the beat poets and lost generation authors back in high school, I’d always wanted to become a writer, to live abroad, and to live by my wits as opposed to punching a clock. This article represents my 498th publication on Seeking Alpha. 178 articles and 320 (occasionally off-color and tangentially-investment-related) blog posts.

Nothing about my life today would have been possible without the unerring support of my wife. She often reads my articles before I submit them – catching spelling mistakes and leaps of logic that I never could. When I announced my intention to leave a predictable and lucrative law practice so I could become a (mostly) uncompensated freelance researcher and writer, she volunteered to (and in fact did) go back to school to get a nursing degree. She then worked the less-desirable shifts at the maternity ward of a downtown hospital supporting her family while I taught myself how to (and sometimes painfully how NOT to) invest our family’s money. Selling off our worldly possessions and moving into a converted convent in the center of Lisbon – that was my idea. And thanks to her investment of patience and confidence, we’ve now built an absolutely extraordinary life for our family. I am beyond grateful.

Be the first to comment