gerenme/E+ via Getty Images

Thesis

From time to time, I hear some confusing arguments about corporate issuances of debt. Given the important and ubiquitous role of debt financing in both corporate finances and also personal finances too, I thought it might be a good idea to offer my two cents in this article. This article is directly motivated by some of the articles I read and readers’ comments I received about the recent offering of debt from Apple (NASDAQ:AAPL). Therefore, the analyses and conclusions should be directly helpful for potential AAPL investors, both bond and equity investors. Although I think the conclusions and insights are general enough that they should be applicable to other corporations as well.

To recap, AAPL announced the issuance of $6.5 billion of bonds last month. The specifics of the offering as quoted below:

- The four-part offering includes $2.3B of 1.400% notes due 2028, $1B of 1.700% notes due 2031, $1.8B of 2.7% notes due 2051 and $1.4B of 2.850% notes due 2061.

- Apple will use the proceeds for general corporate purposes, including share repurchases, dividend payments, and funding capital expenditures and acquisitions.

And the confusion came in several ways. To summarize, the most common forms are:

- I like the bonds better because they yield so much higher than the stock (whose dividend yield is about 0.5% currently). So, the 2028 and 2031 bonds yield about 3x higher than the stock, and the longer terms bonds (2051 and beyond) yield more than 5x higher.

- It must be a bad thing that AAPL has kept adding debt to its balance sheet. And the planned use of the debt makes it even worse (buy back shares and pay dividends). Should not (have not) it making enough money to do these things without borrowing?

And we will address these questions one by one next.

It could be still a good idea to borrow when you already make enough

First, in general, I have nothing against debt financing, either at a corporate level or a personal level, as long as used wisely and responsibly. When corporate debt cost is so low, debt financial is economically advantageous – just like refinancing my mortgage at lower rates.

Furthermore, I have nothing against borrowing even when a corporate (or an individual) is already “making enough money”. The concept here involves the opportunity cost of money (or the cost of capital). Hoarding a pile of cash under the mattress while borrowing at the same time is not necessarily dumb because the pile of cash provides optionality when opportunities strike. A good acquisition opportunity could show up at a time of high borrowing rates in the future.

In a nutshell, it is a good idea to borrow when the borrowing cost is lower than the opportunity cost. And of course, all the trouble is in estimating the opportunity cost of capital. As Charlie Munger famously commented:

“I’ve never heard an intelligent discussion about ‘cost of capital.'”

Munger is absolutely right. And it is beyond the scope of this article to analyze the different ways of estimating the opportunity cost of capital and their problems. But fortunately, in the case of AAPL, the economics is simple because the opportunity cost will be so much higher than its debt financing cost as shown in the figure below.

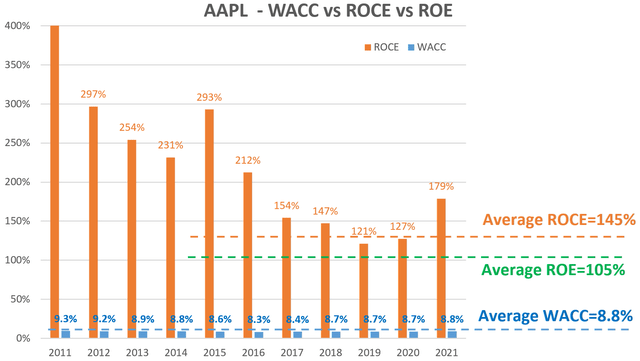

To cite a few numbers, Its Weighted Average Cost of Capital (“WACC”), an average of equity cost and debt cost, has been around 8.8% over the years, much higher than the 1.4% to 2.8% bond yields mentioned above, indicating that its cost of equity is much higher than the cost of debt.

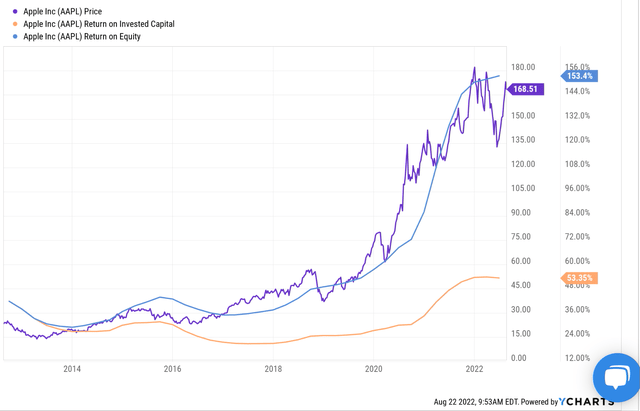

When we turn to common metrics such as ROCE (return on capital employed), ROE (return on equity), and return on capital invested (“ROIC”), the comparison is even more one-sided. Details of the differences in these concepts are provided in my blog article here. As seen, both its ROCE and ROE have been on average over 100% in recent years. And its ROIC hovers around 53% in recent years.

Is it a good idea to borrow NOW?

So, assuming you agree now that it is generally a good idea for AAPL to borrow because its borrowing cost is so much lower than its return on capital, the next question is: is it wise to borrow NOW?

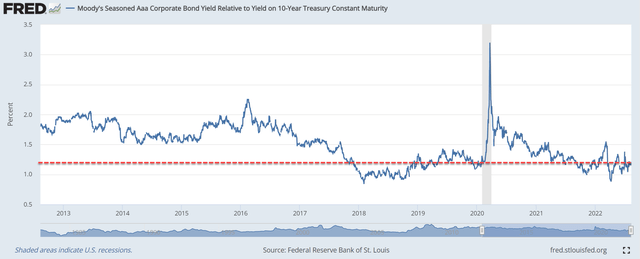

I see now as a very well-chosen timing. The following chart shows Moody’s seasoned Aaa corporate bond yield relative to the 10-year treasury constant maturity yield. As you can see, right now, the yield spread is near a historical low, only at about 1.2% above 10-year treasury rates. And for AAPL, thanks to its superb financial strength and credit rating, its 40-year bond yield is only 0.92% points above Treasuries.

Yield is only one variable

Finally, let’s address the argument for bonds on the basis they yield about 3x to 5x higher than AAPL stock dividends.

Firstly, just to be perfectly clear, I am not against investing in bonds. Both bonds and equity have their place depending on the investment goals and time frames. I am just here trying to clarify that the decision should NOT be made only on the basis of yield comparison.

Bond investors need to consider other factors beyond coupon yields such as duration, sensitivity to interest rate fluctuations, tax consequences, credit risks et al. And similarly, equity investors need to consider a multitude of factors besides dividend yields too.

Even if we just ignore everything else and only focus on yield, comparing bond yields to dividend yields is still misleading. As repeatedly argued in my earlier articles, it is more meaningful to compare earning yield or even better, pretax earnings yield. The reasons are:

- For long-term investors, earning yield is what’s really matters. The reason is that it doesn’t really matter how the business uses the earnings (paid out cash dividends, retained in the bank account, reinvested to further grow the business, or used to repurchase stocks), as long as used sensibly (as AAPL has done in the past), it will be reflected as a return to the business owner. That is why earning yields are more fundamental for long-term shareholders.

- And when we speak of bond yield, that yield is pretax. So, bond yields, when to be compares against equity yields, should be benchmarked against pretax earnings yields.

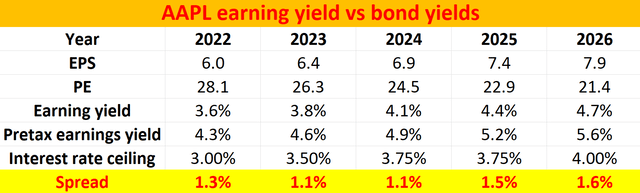

And the next table provides such a comparison for AAPL. Currently, the earning yield of AAPL is about 3.6%, and pretax earnings yield about 4.3% at its current tax rate of about 16.5%. The 10-year treasury yield is about 3%. So AAPL provides a comfortable 1.3% spread above the 10-year treasury yield. Now, let’s consider a projection under the following assumptions: A) its tax rate remains at 16.5%, B) its earnings grow at 7%, at the conservative end of consensus estimates, and C) a really aggressive interest rates scenario in the next few years with 10-year treasuries reaching 4% in 2026.

As seen, even under these dramatic assumptions, AAPL would always provide a comfortable yield spread above the 10-year treasury rates. Furthermore, the yield spread is and would remain higher than the current yield spread between its 40-year bond and treasury rates (0.92% as aforementioned).

Final thoughts and other risks

Finally, let me reiterate that I am not here to argue against the AAPL bonds (or bonds in general). Both bonds and equity have their places and I hold both myself. It all depends on the investment goals and time frames. Bond investments are obviously a good idea when we have to meet a given financial obligation at a given time (like paying for our kid’s college tuition in 5 years). On the negative side, bond investments typically have more limited upside than equity investments like what we just compared.

I am just here trying to clarify two confusions surrounding bonds. Firstly, it is perfectly ok, or even wise, to borrow when a company is already making enough money. And secondly, the choice between investing in debt and equity should NOT be made only on the basis of yield comparison. If this logic is sound, then the debt of a company that pays no cash dividend is always automatically and indefinitely better than its equity. And lastly, if the yield is to be compared, it’s more meaningful to compare bond yields to pretax earnings yields.

Finally, one more cautionary word for bond investors. A common sense about bond investing is their “fix income” nature. In the AAPL example above, you could argue that A) yes, bond yields are lower than earnings yield, but B) my bond yields are locked in for 40 years while earnings yield can change. It is not entirely true (like many common senses) because treasury rates and inflation can vary, which could cause the real bond yield to change (and the price of the bonds too).

For example, it is true that AAPL’s 40-year bond is locked in for the next 40 years at 2.85%, which again is 0.92% above treasury rates currently. However, as treasury rates change, the yield spread would change too, just like its equity yield. And I do not believe the “fixed yield” would mean too much should the yield spread between its bond and treasury rates become zero or even negative. When/if that happens, I would just forget about the 2.8% “fixed income” on my AAPL bonds and trade them for treasury bonds.

Be the first to comment