gremlin/E+ via Getty Images

Introduction

Zombie companies are entities that should be bankrupt, but are still in business. There are several loose definitions of what characterizes a zombie company. What they all have in common is that such companies cannot sustain their operations without outside help. Of course, as shareholders, we have a vested interest in the sustainability of our companies’ operations, not least because we cannot rely on fixed compensation such as an interest payment, and because we have only a residual claim on the company’s assets. However, zombie companies concern us all because they can have a significant impact on society as a whole.

In this article, I will discuss ways to identify zombie companies, or those on the verge of becoming zombie companies, and point out risks to their stakeholders and society as a whole. I will explain why zombie companies are a growing concern in the current environment, and highlight the reasons behind the seemingly ever-increasing appearance of such companies. I also will discuss some financial metrics that I use in evaluating the quality of my holdings. They make it possible to identify operational problems at a very early stage, long before a company can be labeled a zombie.

Three Typical Characteristics Of Zombie Companies, And Why Even Newly Listed Companies Can Be Zombies

The term “zombie company” is only very vaguely defined. There are several characteristics that can indicate that a company is more dead than alive. Typically, zombie companies are characterized by ever-increasing debt and consequently deteriorating balance sheet quality. From the ever-increasing debt, one might conclude that the company is unable to repay the principal.

However, the apparent inability of a company to repay its debt is per se a problematic distinguishing feature, since larger companies in particular operate with a more or less large amount of debt that they do not intend to repay, but rather to refinance. It follows that a zombie company can be distinguished from a healthy one by the fact that the latter would theoretically be able to repay the outstanding principal if it intended to do so. Take, for example, Altria Group (MO), the well-known tobacco company. Its net debt rose from less than $10 billion at the end of 2010 to $10.6 billion in 2015 and ballooned to $24.5 billion by the end of 2020 in a – so far – unsuccessful attempt to diversify the business away from traditional smoking products. Over that period, Altria’s equity ratio fell to 6%, and by the end of 2021 it was actually negative. However, considering that Altria operates a highly reliable and extremely profitable business with a wide economic moat and low capital expenditures, it would be foolish to conclude that it’s a zombie company. When Altria’s net debt is considered in the context of its ever-increasing free cash flow, even the last doubts are removed, as the company could currently pay off all of its debt within three years if it hypothetically suspended its dividend and share buybacks.

It follows that investors should never look at net debt in isolation when trying to identify a potential zombie company. Debt must be viewed in relation to the company’s earnings, or better, since earnings are fairly easy to manage, to its sustainable free cash flow. I recently published a detailed article explaining how to determine a company’s actual free cash flow. Personally, I think a net debt to free cash flow ratio of three or less is generally not problematic, although the cyclicality of the business must also be considered.

The situation becomes problematic when a company takes out loans to compensate for a decline in operating profitability. But even a company with a stable business model can become a zombie if it has to invest heavily and finance these investments with more and more debt. As debt increases, so do the costs of servicing it, and interest payments become an increasingly large part of the company’s obligations. Therefore, a good way to identify zombie companies is by the interest coverage ratio, which relates a company’s operating profit to its interest obligations. The above also applies here, and I personally prefer to use pre-interest free cash flow instead of operating profit. While this approach does not take into account a tax-shield effect, it’s still a more transparent way to assess a company’s debt servicing ability than looking at earnings on the income statement. The higher a company’s interest coverage ratio is, the better, of course, but as mentioned above, the cyclicality of the business must also be taken into account. A declining interest coverage ratio – due to a declining free cash flow and/or increasing interest obligations – should be critically evaluated.

It follows that a rising interest rate environment acts as a kind of fire accelerant, driving unprofitable and over-leveraged companies out of business sooner or later. Such an environment has a “cleansing effect” as it automatically separates the wheat from the chaff over longer periods of time. However, for this natural selection mechanism to work, the forces of the free market economy must not be interfered with (see next section).

As a third aspect, the business model should also be scrutinized. A company with a defunct business model or one that’s suffering from increasingly fierce competition has a high probability of becoming a zombie, assuming management fails to diversify or reorient the business in a timely and appropriate manner. Signs that a company’s business model is becoming obsolete include a lack of organic revenue growth, an increasing focus on acquisitions (sometimes at desperate valuations), shrinking profit margins, and diminishing returns on invested capital.

Since the future viability of a business model cannot always be conclusively determined, I diversify my holdings broadly, focusing for the most part on established companies that have stood the test of time, provide everyday goods or services, and are difficult to imagine ceasing to exist in the future. Examples include large consumer staples companies such as Procter & Gamble (PG), worldwide diversified tobacco companies such as British American Tobacco (BTI, OTCPK:BTAFF), large pharmaceutical companies such as Bristol Myers Squibb (BMY), or well-diversified conglomerates such as Johnson & Johnson (JNJ), which operates in the medical devices, pharmaceuticals, and consumer products sectors. As a rule of thumb, Morningstar’s economic moat rating is a good indicator of company strength, and it just so happens that all of the above companies have a wide economic moat rating. Obviously, the old rule of sticking with blue-chip companies applies in this context, as it’s very unlikely that large global companies will become zombies. The impact of the rare, but probably inevitable, pipe bursts can be adequately mitigated by proper diversification.

High and rising debt, low and declining interest coverage, and an outdated business model are typical characteristics of zombie companies. A good example of a company that is very likely a zombie is Gogo Inc (GOGO), the world’s largest provider of broadband connectivity services in the airline industry. The likely future obsolescence of Gogo’s business model is easy to grasp given the rapidly changing world of connectivity technologies, and the company’s typically weak positive or negative profit margins, negative returns on capital, poor working capital management, and deteriorating balance sheet also are very telling. Gogo’s interest coverage ratio was below one in 2019 and 2020, meaning the company was not even able to service its debt. The company’s free cash flow also was negative in those years, but things looked a little better from a cash flow perspective in 2021.

Another notable example is the troubled retailer Bed Bath & Beyond (BBBY), whose decline was largely due to incompetent management that, at the most unfortunate time, bought back shares with billions of borrowed dollars while selling privately held stock and, above that, papering-over declining sales with aggressive but unsustainable discounting. As a result, BBBY, which I covered in July 2022, has ultimately become dependent on the goodwill of its creditors. Of course, the oft-cited dominance of online retailers like Amazon (AMZN) can only be seen as part of the reason for BBBY’s decline, as the success of other brick-and-mortar retailers like Best Buy (BBY) shows.

Depending on how strictly the criteria are defined, even large companies can be considered zombie companies. Given its significantly increased debt and losses since 2019, largely due to the 737 MAX disaster and government imposed measures related to the COVID-19 pandemic, Boeing (BA, see my recent article) can theoretically be considered a zombie. However, given the recent surge in demand for its aircraft, the resolving of the 737 MAX situation (with the noteworthy exception of China), and the broad diversification of this otherwise very cyclical company into the defense sector, I think it’s inappropriate to consider Boeing a zombie company, also because it operates in a duopoly and the switching costs for its products are very high.

But what about the newly emerged companies that appear to be the innovators of tomorrow? Some of these companies have little or no debt, so they are not as easy to identify. Many of these companies emerged in 2020 or 2021, years that were marked by a speculative frenzy. There was plenty of excess capital, and interest rates were lower than ever. In addition to conventional initial public offerings, special purpose acquisition companies (SPACs), so-called meme stocks (or otherwise hyped stocks), and also cryptocurrencies (especially new altcoins) saw huge inflows, especially from young retail investors. Companies that are unlikely to ever become profitable or lack a proper business model have been allowed to flourish. Names like Uber Technologies (UBER), DoorDash (DASH), and Peloton (PTON) come to mind. Some of these companies are largely or exclusively equity financed and can look quite solid from a balance sheet perspective, as they oftentimes have significant cash on hand. However, since they need to constantly issue new shares to stay afloat, a good indicator of such a “young zombie” is a constantly rising share count. For companies that appear to have plenty of cash on hand but are not (yet) profitable, the cash burn ratio can be helpful. This ratio puts cash on hand in relation to the sum of negative cash flow from operations and capital expenditures. The result indicates how many periods (depending on whether quarterly or annual cash flows are used) the company can get through before it has to tap its loyal shareholders or other liquidity sources. I think it depends on one’s personal risk tolerance as to what magnitude of cash burn ratio can be considered “reasonable.” For my part, I would not invest in such companies and therefore cannot give a specific ratio.

In summary, there are a few ways to spot zombie companies or those about to enter the realm of the living dead. A quick look at the current balance sheet, taking into account data from a few years ago, is usually enough to determine if a company is in a downward spiral. However, it’s also important to consider the company’s business model and its long-term prospects. In this context, Jeremy Siegel’s highly recommended book with the telling title “The Future for Investors: Why the Tried and the True Triumph Over the Bold and the New” comes to mind. In addition to looking at the balance sheet and critically evaluating the business model, a review of interest coverage in terms of operating income or, better yet, free cash flow can be very revealing. Finally, investors should be careful not to take a seemingly solid balance sheet at face value – it could be the case that the newly formed company is in need of capital increases that dilute existing shareholders. Such companies, which depend on the availability of “easy money” face an increased risk of bankruptcy as market conditions tighten and investors turn to more solid investments.

Why Zombie Companies Are Not Only Dangerous For Creditors And Shareholders

In my opinion, it’s appropriate to distinguish between old and young zombie companies according to the above criteria. I consider the former to be more dangerous than the latter.

Young zombies are dangerous because they can be the breeding ground for a speculative bubble. If shares of such companies are bought on credit, the bursting of a bubble can trigger margin calls that lead to a self-reinforcing downward spiral that can take the shares of otherwise solid companies with it. If the bubble was large enough and the entire market subsequently collapses, this can have consequences for the banking sector, as contagion can spread to loans that were collateralized by equities. It should be clear that it is not only retail investors who speculate in such equities (sometimes referred to as “dumb money”), but also hedge funds and other large corporations, often referred to as “smart money.” Consider in this context the relatively recent example of the Archegos hedge funds that led to billions of dollars in losses at Nomura (NMR) and Credit Suisse (CS). Besides such potentially systemically relevant effects, the destruction of capital results in less money available to investors, which in turn can have a negative impact on consumer spending. In extreme cases, the bursting of a speculative asset bubble can lead to an economic downturn, as the past has shown.

Old zombies, companies on the verge of becoming zombies due to an outdated business model or financial mismanagement, and older startups that have not made the transition to profitability are more dangerous overall because the systemic threat develops over a longer period of time, is less noticeable, and can be associated with more severe consequences. Here is a very simplified explanation:

An economic downturn is accompanied by insolvencies, which have an impact on banks’ balance sheets. It’s in the nature of banks that their balance sheets are leveraged, so credit losses deplete equity by orders of magnitude faster than they would on a purely equity-financed balance sheet. What’s commonly referred to as the “systemic importance of major banks” is one reason that interest rate cuts and asset purchase programs have become the primary tools to stabilize our fragile financial system during periods of turbulence. Put simply, by buying up assets and acting as lenders of last resort, central banks can alleviate stress on the banking system and limit downward spirals that would otherwise peak in no-bid markets, with potentially devastating consequences for markets, as the recent example in the United Kingdom shows.

It should be clear, however, that interest rates serve an important signaling function, similar to that of pain in the body. The higher the interest rate or cost of equity, the higher the risk to the holder of a bond or equity security of not being made whole or being adequately compensated. Higher risk carries the potential for higher returns, but there’s no free lunch. However, if interest rates are artificially lowered, e.g., by lowering the federal funds rate and/or through bond-buying programs (as demand for bonds increases, their yields decrease) and kept low for a considerable period, there’s a temporary free lunch. When companies or entire countries realize they will be bailed out if need be, the likelihood of malinvestments increases, imprudent risk taking is rewarded and the natural cleansing effect of the free market is overridden. Clearly, the COVID-19 pandemic and the associated financial support have only added fuel to the fire.

In such an environment – and it’s easy to see that we have been living in such an environment for quite some time – zombie companies thrive. A low interest rate environment not only encourages malinvestments, but also helps the dead live longer. Companies that would have been barred from borrowing in a normally operating market economy are still getting loans because investors have been pushed out further on the risk curve. At the same time, healthy companies may be disadvantaged in the lending process. In this environment, inefficient companies or those with an ailing or outright failed business model no longer fall prey to the natural forces of capitalism. In extreme cases, they may even impede social progress by also tying up workforce in unproductive jobs and occupying other resources. This is particularly true for increasingly bureaucratic societies. Taken as a whole, zombie companies pose a systemic threat, not only to the banking system, but understandably also to companies that provide subscription-based business services in a monopolistic manner, such as Microsoft (MSFT) or Adobe (ADBE). However, it’s impossible to quantify this particular risk and determine whether it is actually material.

It’s an inconvenient truth, but politicians have an incentive to kick the can down the road, because they can only stay in power for a certain period and understandably want to avoid being held accountable for policies that are associated with direct societal impact, such as leading to increased unemployment.

However, the further the can is kicked down the road, the more serious the problem gets. First, the number of zombies increases over time, as their behavior can be literally contagious. Second, systemic risk increases due to the interconnectedness of zombie companies, healthy companies, and lenders. Third, the longer the process continues, the more sensitive the zombies are to exogenous shocks. In turn, the required stimulus increases each time a downturn is avoided through bailouts. In the long run, the abjuration of capitalism and the supposed brutality of its – ultimately healthy – creative destruction can lead to chronic stagnation of entire economies.

Now, it’s likely impossible to estimate what percentage of zombie companies an economy can sustain before their collective poses a serious systemic threat. I’m not in a position to estimate the tipping point, but I’m concerned. The Federal Reserve mentioned in a July 2021 article that in 2020 about 15% of all companies in the U.S. were zombie companies (10% publicly traded, about 5% privately held).

Because of the worrying but understandable developments, I’m a big proponent of the hawkish role the Federal Reserve has adopted. While we should not hope for economic malaise, I think that a downturn is necessary to bring market forces somewhat closer to equilibrium.

However, due to the fact that corporate debt typically has a duration of several years, the effects from rising interest rates will only become visible rather slowly. In itself, this delayed impact is positive, as zombie companies thus gradually go out of business. However, for this and several other reasons, the onset and the magnitude of the broadly expected recession is unclear. In any case, the hypothetical (albeit probably unlikely) case of a downward spiral triggered by the failure of zombie companies across the board is one reason why I focus only on the most reliable companies for the most part of my own portfolio. In the final part of this article, I will discuss the key characteristics of most of my core holdings and share some examples.

How I Make Sure That I Do Not Own The Zombies Of Tomorrow

In the following, I will go into several aspects, some of which I have already briefly addressed in the second part of this article and that I take into account when investing in companies. However, I will not reiterate the importance of a solid and future-proof business model. Of course, the core of my portfolio consists of companies with business models that have stood the test of time.

By following these rules, I ensure that I do not own a zombie or that I do not own a company that could become a zombie in the near future. At the same time, these principles are typical characteristics of very solid companies that can also withstand a severe economic downturn.

Low Cyclicality, Dependable Earnings And Growing Cash Flow

Although I have a certain proportion of cyclical companies in my portfolio, most of my holdings are relatively insensitive to economic cycles. These include, in particular, consumer staples companies such as Procter & Gamble (PG), which manufacture everyday items. However, because consumers trade down during times of lower disposable income, such companies that sell mostly branded goods can also see weaker profit growth or sometimes even a decline during a recession. The big names in consumer staples have the added advantage of operating globally. In this way, the impact of a domestic economic downturn is somewhat mitigated. At the same time, however, the earnings of such companies – if they’re based in the U.S. – are subject to significant exchange rate risk. Notable examples include Colgate Palmolive (CL) and Philip Morris (PM), the latter of which operates only outside the U.S., but is expected to re-enter the market through the acquisition of Swedish Match (OTCPK:SWMAY, OTCPK:SWMAF) (see my recent article).

Low cyclicality is usually accompanied by very reliable earnings and cash flows. In my opinion, the well-known FAST Graphs tool does a very good job of illustrating the earnings quality of a company when viewing “adjusted (operating) earnings.” To illustrate, Figure 1 shows the FAST Graphs chart for PepsiCo (PEP), the company behind world-class brands such as Pepsi-Cola, Gatorade, Tropicana, SodaStream, Mountain Dew, Lays, Doritos, Cheetos, and Quaker (see my recent comparative analysis with The Coca-Cola Company, KO). The company’s earnings have been extremely reliable, and even the Great Financial Crisis has left the company’s earnings completely unaffected. As an aside, switching to the unadjusted numbers helps identify one-time charges that were not reported in the adjusted earnings. A company with recurring and significant charges should be examined more closely accordingly.

Figure 1: FAST Graphs charts for PepsiCo [PEP], based on adjusted operating earnings (with permission from www.fastgraphs.com)![PepsiCo [PEP] adjusted operating earnings](https://static.seekingalpha.com/uploads/2022/12/1/49694823-16698995033252864.png)

A look at the “Analyst Scorecard” in FAST Graphs or the “Earnings Surprise” tab on Seeking Alpha can also be very helpful. In this context, the large pharmaceutical company Merck (MRK) is worth mentioning, as its earnings are usually very much in line with consensus estimates (Figure 2). Of course, as a pharmaceutical company, Merck’s stock can be relatively volatile, and its earnings depend heavily on the company’s success in research and development. Merck is currently in a particularly good position, and its blockbuster cancer drug Keytruda (pembrolizumab) is on track to become the world’s best-selling drug by 2026.

Figure 2: Comparison of Merck’s [MRK] actual earnings with consensus estimates (taken from Merck’s stock quote page on Seeking Alpha)![Comparison of Merck's [MRK] actual earnings with consensus estimates](https://static.seekingalpha.com/uploads/2022/12/1/49694823-16698995398462782.png)

As an income investor, it’s important to focus on companies with reliable cash flow. Like earnings, free cash flow should grow at a significant rate, otherwise the growth of cash returns to shareholders may be compromised. Of course, a company that is able to pay a dividend is unlikely to be a zombie, but it’s still important to understand the actual source of cash flow, i.e., whether a company is generating organic free cash flow or merely tapping the credit or equity markets to obtain funds.

High Excess Return On Invested Capital

Financial textbooks offer a plethora of profitability metrics. I think of return on equity, return on assets, gross margin, capex ratio, etc. However, return on invested capital – ROIC – is the metric I rely on the most because it relates after-tax net operating profit to actual invested capital. This metric beautifully illustrates why companies with asset-lean business models can lead to disproportionately high shareholder returns. By comparing ROIC with the company’s weighted average cost of capital – WACC, it’s possible to determine whether returns above the cost of capital are actually being generated (which is crucial for long-term returns).

WACC is the weighted average of the cost of equity and the cost of debt, the latter of which can be calculated from the company’s debt and its rates. The former is more difficult or probably impossible to determine, but of course depends on the risk-free interest rate (in this case the interest rate on long-term government bonds). In theory, the cost of equity is determined using the Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM), which takes into account the volatility of a stock (beta). It’s debatable whether the cost of equity should be determined this way. Personally, I do consider beta but put an emphasis on the operating aspects of the company. Whether an investor believes the CAPM-derived cost of equity is reasonable is irrelevant to the argument, as long as it’s roughly reasonable. Clearly, blue-chip companies such as Johnson & Johnson or Unilever (UL) have comparatively low costs of equity. I consider values in the 7% to 8% range to be reasonable, resulting in slightly lower WACCs due to the lower costs of debt. The take-home message is that a company should be able to consistently generate a return that is well above its WACC, and that is certainly the case for both companies, as Figure 3 shows. Note that the decline in JNJ’s ROIC in 2017 was due to a one-time provision for taxes on income of $16.4 billion. In contrast, Unilever’s ROIC has declined in recent years, which is indicative of the company’s known operational challenges. While I own shares of both companies, I consider Unilever a riskier proposition because of these problems, but of course I do not consider Unilever to be a zombie company.

Figure 3: Returns on invested capital of Johnson & Johnson [JNJ] and Unilever [UL] (own work, based on data supplied by Morningstar)![Returns on invested capital of Johnson & Johnson [JNJ] and Unilever [UL]](https://static.seekingalpha.com/uploads/2022/12/1/49694823-16698996201403532.png)

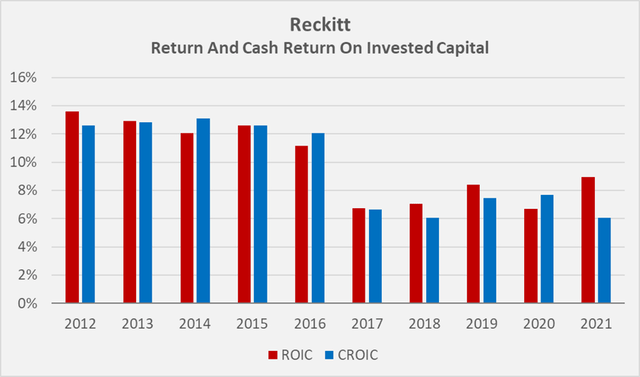

Historical ROICs are readily available on many financial websites, and even with only a rough idea of a company’s WACC (GuruFocus provides CAPM-based values, for example), the extent to which excess returns are being generated can be assessed. As an aside, I always consider free cash flow to determine whether the company’s seemingly high returns on invested capital translate into actual cash returns. When calculating cash return on invested capital (CROIC), the cost of equity rather than WACC is the appropriate comparator. Importantly, a discrepancy between ROIC and CROIC should be critically evaluated, as illustrated by the example of the UK consumer staples company Reckitt (OTCPK:RBGPF, OTCPK:RBGLY) in Figure 4. I will not elaborate on the challenges here, but refer interested readers to my article on the company.

In summary, keeping an eye on a potentially negative trend in ROIC and CROIC can be very helpful in assessing whether a company is on the verge of becoming an unproductive zombie.

Figure 4: Return and cash return on invested capital of Reckitt [RBGPF, RBGLY]; note that in the process of obtaining CROIC, free cash flow was normalized with respect to stock-based compensation expenses, working capital movements and recurring impairment and restructuring charges (own work, based on the company’s 2010 to 2021 financial statement)

Manageable Debt And A Comfortable Interest Coverage Ratio

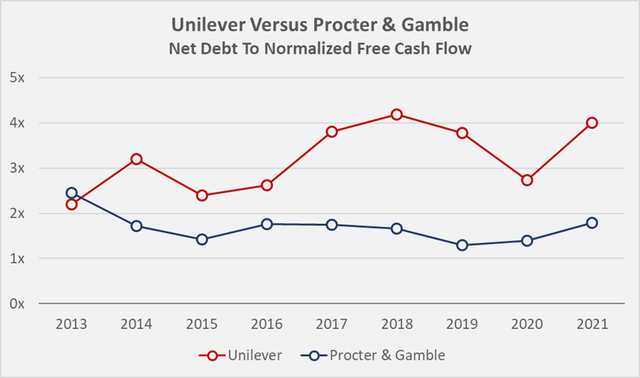

As mentioned earlier, putting an emphasis on manageable debt largely saves investors from falling into the trap of owning a zombie company. When evaluating the quality of a company, it’s important to look not only at debt in absolute terms, but also in relation to earnings metrics such as free cash flow, as noted earlier. The contrasting trends of consumer goods giants Unilever and Procter & Gamble (Figure 5) illustrate this point very well and confirm that Unilever is indeed a company to watch somewhat closer, while I’m obviously not suggesting that it is a zombie company or on the verge of becoming one.

Figure 5: Net debt to normalized free cash flow is an illustrative way to review the leverage of companies, as the example of Unilever [UL] and Procter & Gamble [PG] shows (own work, based on the companies’ 2011 to 2021 financial statements).

In addition to increasing debt, weakening interest coverage is a typical characteristic of a zombie company or one on the verge of becoming one. Figure 6 shows the interest coverage in terms of pre-interest normalized free cash flow of Hormel Foods (HRL), an extremely conservatively managed food company, compared to Reckitt, the consumer staples company mentioned earlier. The latter company’s operational challenges have already been touched upon above and will not be elaborated on in this article, but its declining interest coverage ratio is certainly something to keep an eye on. Hormel’s interest coverage ratio rose for several years, indicating a strengthening business, but began to decline in 2018. That Hormel is suffering from operational problems, however, would be a hasty and incorrect conclusion. The simple fact is that the company does not typically use debt to finance its operations. Its balance sheet is among the most solid in the industry, as I detailed in my article on the company, and Hormel has only taken on a – manageable – amount of debt to stem the purchase of the Planters nut business from Kraft Heinz Company (KHC) in 2021.

In summary, a weakening interest coverage ratio should not be over-interpreted, but it’s important to be able to identify the reasons for it. Zombie companies typically have interest coverage ratios below 1 or no positive cash flow at all. I determine appropriate interest coverage ratios on an industry-specific basis, taking into account the positioning and size of the individual company.

Figure 6: Historical interest coverage ratios of Hormel Foods [HRL] and Reckitt [RBGPF, RBGLY]![Historical interest coverage ratios of Hormel Foods [HRL] and Reckitt](https://static.seekingalpha.com/uploads/2022/12/1/49694823-16698997808024995.png)

A Conservatively Structured Debt Maturity Profile

Finally, it’s also worth walking the extra mile of analyzing the maturity profiles of one’s holdings. In this way, unpleasant surprises can be avoided at a very early stage, and the structuring of the debt profile can also be an indication of the quality of the company’s treasury department. Comcast (CMCSA), the multinational telecommunications conglomerate, is a very good example in this context. Several analysts (rightly) point out the company’s high debt burden. However, it’s important to consider how stable Comcast’s free cash flow is (Figure 7) and how comfortably structured its maturity profile is (Figure 8). In this context, CEO Brian Roberts’ remarks during the Q2 2022 earnings conference call are very telling:

I think all parts of the company are really doing a great job in some interesting times. By the way, our treasury department went out while interest rates were low and we’ve basically repriced the whole balance sheet for something on the order of 18 years average maturity at record low rates. So I feel we are able to return capital to shareholders. I think that’s been a real focus and I think we did it again this quarter. – Brian Roberts, CEO of Comcast

Figure 7: Comcast’s [CMCSA] free cash flow, normalized for working capital movements, stock-based compensation expenses and impairment charges (own work, based on the company’s 10-Ks) Figure 8: Comcast’s [CMCSA] debt maturity profile at the end of 2021 (own work, based on the company’s 2021 10-K)![Comcast [CMCSA] free cash flow](https://static.seekingalpha.com/uploads/2022/12/1/49694823-1669899807353896.png)

![Comcast [CMCSA] debt maturity profile](https://static.seekingalpha.com/uploads/2022/12/1/49694823-1669899840774307.png)

Key Takeaways

Zombie companies are characterized by a high level of debt that increases over time. Unlike leveraged companies that choose not to repay their debt, zombies are unable to do so. Therefore, it’s critical to review a company’s debt relative to the cash flow it can generate on a regular basis. A declining interest coverage ratio is a potential sign of trouble, but acute zombies typically have an interest coverage ratio of less than 1. The company’s business model should also be examined for potential signs of obsolescence, such as acquisitions at desperate valuations or a lack of organic growth.

However, recently IPOed companies can also be zombie companies, and they may not even be recognizable by a weak balance sheet. Repeated issuances of stock and consistently negative operating cash flow are signs of what I call “young zombies.” Such companies are dependent on the availability of “easy money” and have an increased risk of bankruptcy if market conditions tighten. Young zombies are dangerous because they can form the breeding ground for a speculative bubble. The bursting of such a bubble can have potentially systemic consequences.

Central banks stabilize our financial system by lowering interest rates and buying up assets during times of financial turmoil. However, in a prolonged low interest rate environment, zombie companies thrive because the cost of servicing debt is low and investors are chasing yield. Inefficient companies or those with an ailing or outright failed business model no longer fall victim to the natural forces of capitalism. Politicians have an incentive to kick the can down the road because they understandably do not want to be held accountable for actions that have a direct negative impact on society, such as rising unemployment. With each crisis, the problem worsens and the systemic threat increases because the cleansing effect of a free market economy no longer exists. In the long run, the abjuration of capitalism and the supposed brutality of its – ultimately healthy – creative destruction can lead to chronic stagnation of entire economies.

As individual investors, we can only focus on our own holdings and ensure that we do not own the zombie companies of tomorrow or worse, outright zombie companies. The following characteristics do not occur in zombie companies and are typical of companies that can survive even a severe economic downturn:

- A business model that has stood the test of time

- Low cyclicality, dependable earnings and growing cash flow

- Meaningful and at least stable excess return on invested capital, no significant discrepancies between operating earnings and free cash flow

- Manageable debt and a comfortable interest coverage ratio

- A conservatively structured debt maturity profile

Thank you very much for taking the time to read my article. In case of any questions or comments, I am very happy to read from you in the comments section below.

Be the first to comment