Kwarkot/iStock via Getty Images

Much discussion relating to REITs revolves around the “Cap Rate” of properties purchased or sold. One is now seeing comments and questions from investors wondering whether inflation will cause property values to plummet and cap rates to soar.

January saw significant declines in stock price across the REIT sector. Fear of inflation seems a likely cause. What should you do? Invest more? Sell?

Here we look for answers to part of these questions. From a very big-picture perspective, we examine what Cap Rates are and why they change.

What they are is simple. Any property produces a Net Operating Income (“NOI”), generally defined as Revenues less Property Operating expenses. The ratio of NOI to the Property Value is the Cap Rate.

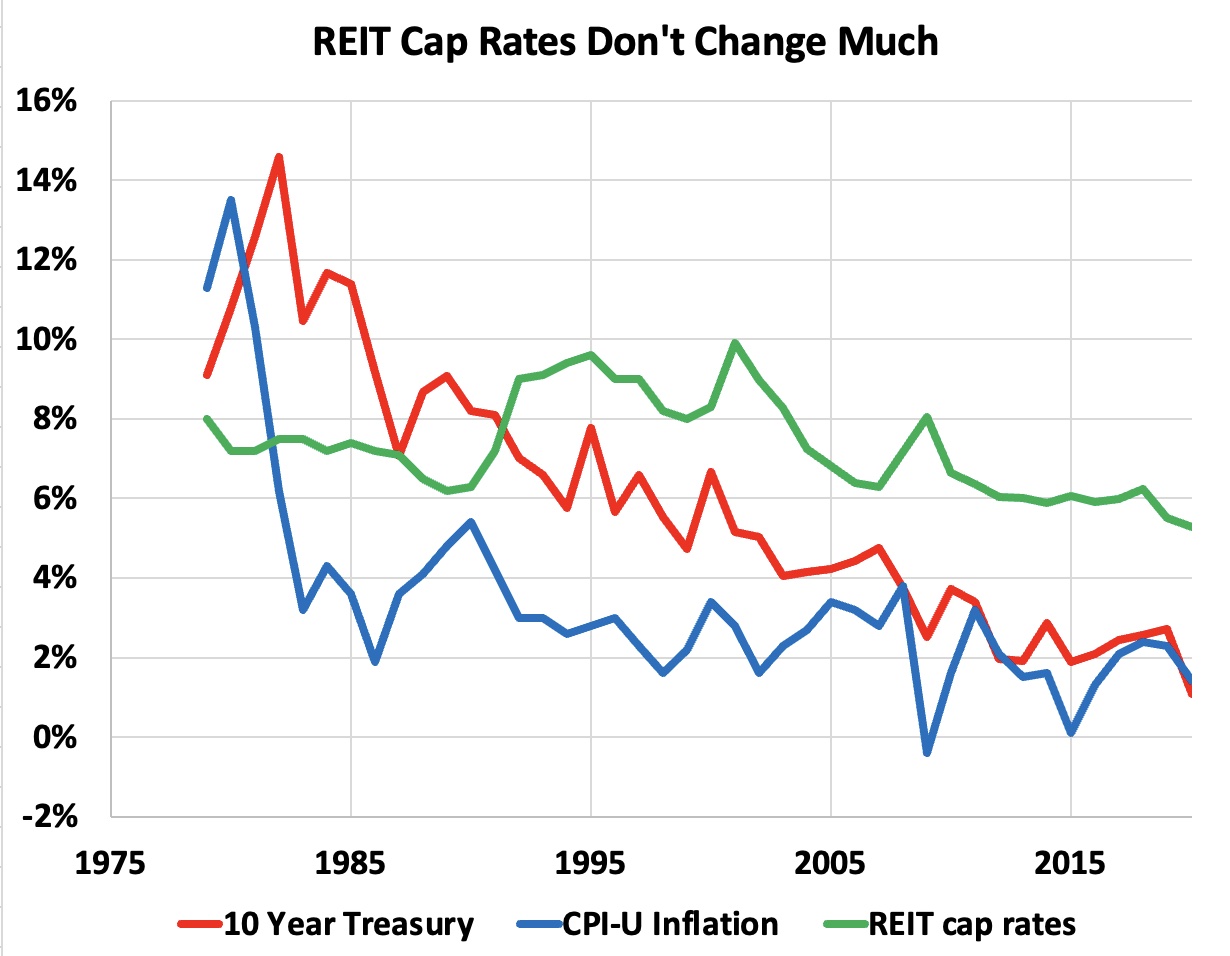

What is remarkable is how little Cap Rates have changed over time.

Here I took typical Cap Rates from the NAREIT plot back to about 2000 and Cap Rates before that from an MIT paper. The plot shown compares Cap Rates, Inflation Rate, and Treasury Rate since 1979.

RP Drake

Overall, Cap Rates have changed much less than Inflation Rates or Treasury Rates. They have been dropping steadily in recent years, though, as we will discuss further below.

In a historic context it is notable that Cap Rates were below Treasury Rates for an extended period in the 1980s and before. During that era, real estate investing could not be based on the spread between these two, as is widely assumed today.

I will visit that topic in a distinct article. Today the focus is Cap Rates and why they change, from a big-picture perspective.

The Macro Context

One of the fundamental drivers of change in the real estate markets is the rate of inflation, shown above.

Discount rates for real estate also move with inflation rates, on average. The spread between these rates changes with time.

In the following, we will model the main trend. We will model discount rates as some market-determined real rate, adjusted upward by the price inflation rate,

discount rate = real rate + inflation rate,

and show results for diverse real rates.

Property Values and Cap Rates

To make the following argument rigorous one ought to adjust cash NOI as needed to include all property-specific expenses, such as maintenance capital expenditures (“capex”).

One can impact the NOI of a property by upgrading it, rebranding it, or improving its occupancy. Also changes in the markets create changes in rents.

Once the property is stable, though, and averaged across cycles, NOI will grow with price inflation. The Property Value then is the discounted value of the NOI over time.

Modeling this on a long-term basis, one has

Property Value =

NOI x (1+inflation rate)/(discount rate – inflation rate).

We can invert this to get a Cap Rate, defined as the ratio of NOI to Property Value.

Cap Rate = (discount rate – inflation rate)/(1+inflation rate).

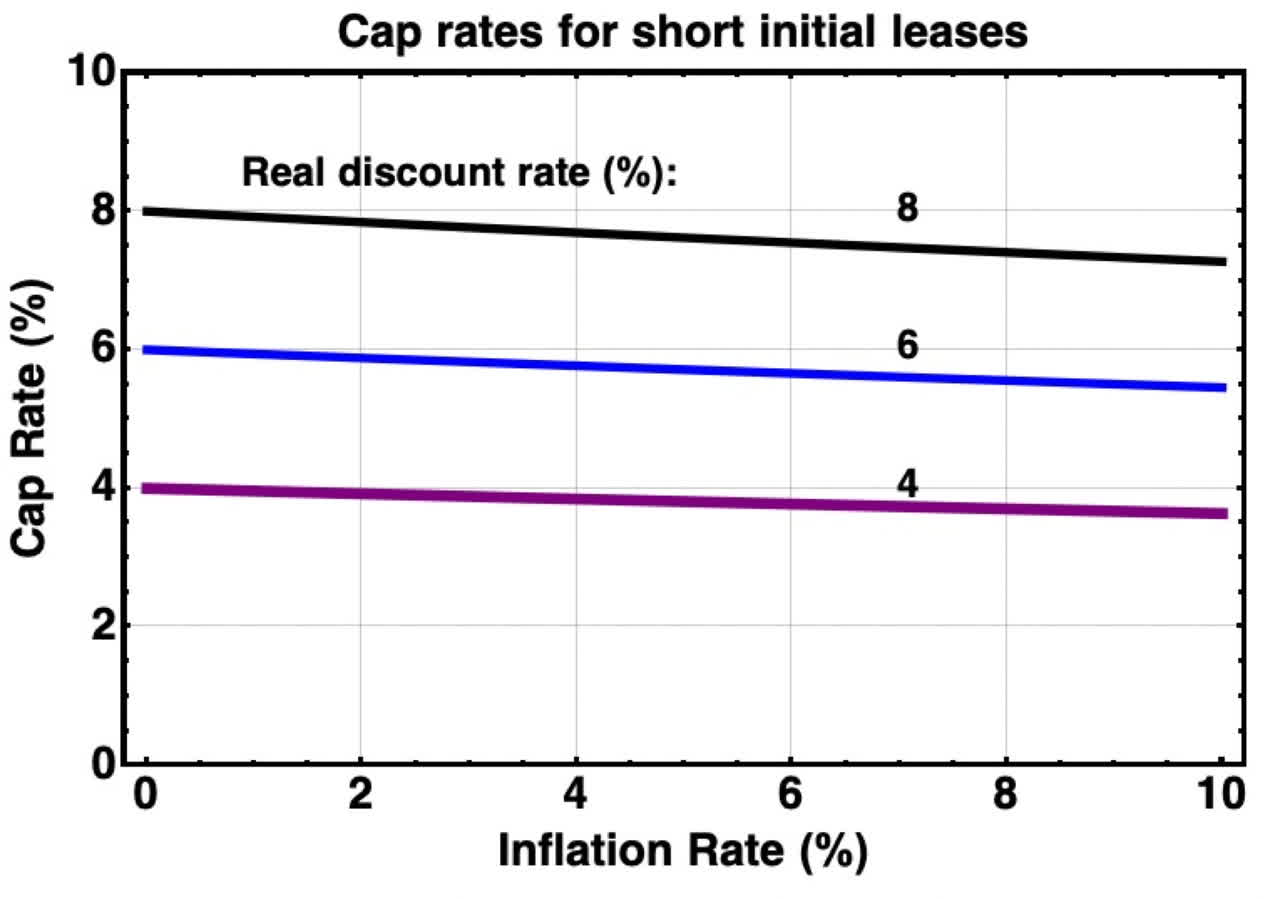

Using the approximation discussed above to model the discount rate, the Cap Rate becomes

Cap Rate = real rate/(1+inflation rate).

This is a remarkably weak dependence, shown here for real rates of 4%, 6%, and 8%, on the assumption that leases are short so there are no delays in Income.

RP Drake

What we see is remarkably little change in cap rate across a very wide range of inflation rates, at fixed real return.

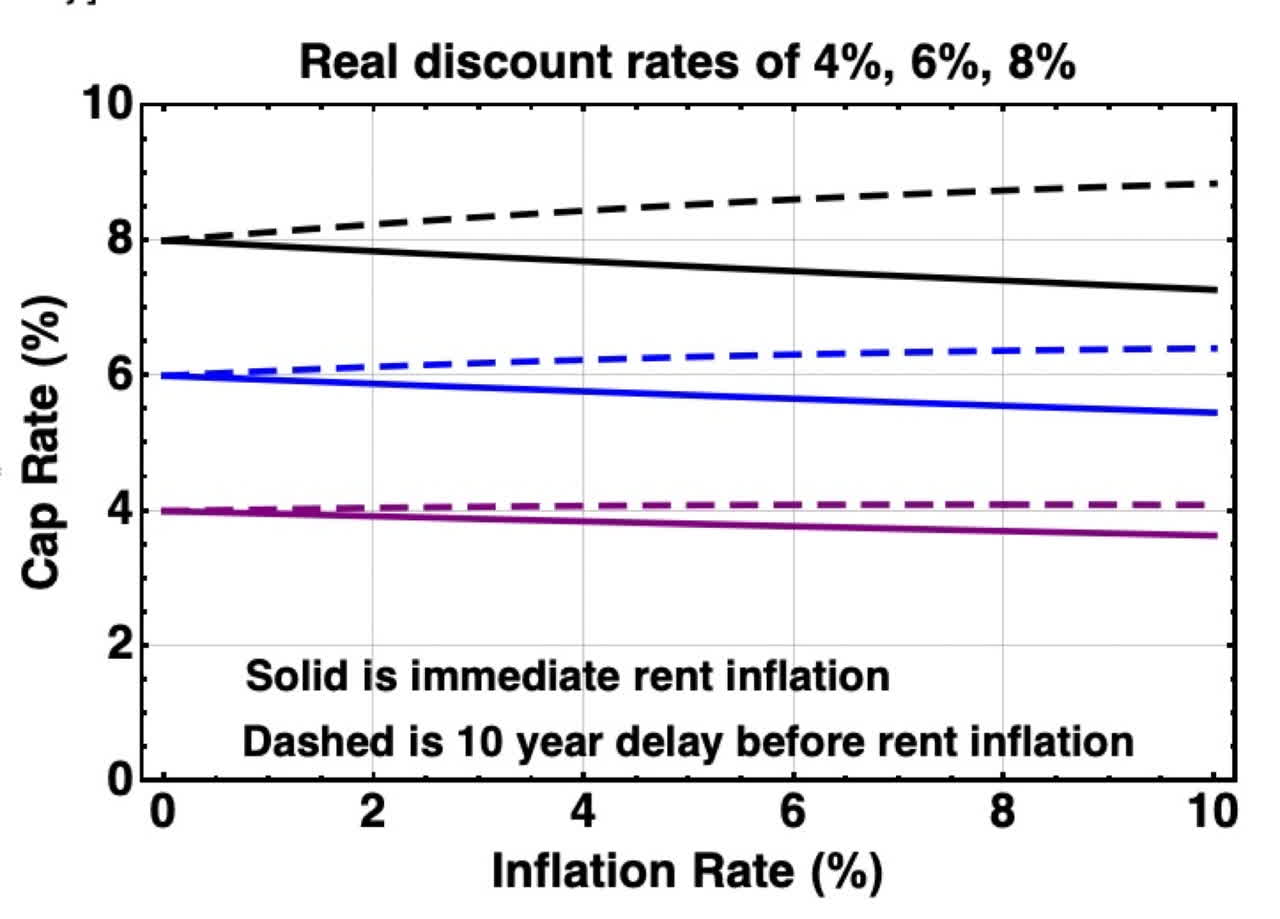

Investors often become concerned by long leases in the context of inflation, because they may prevent rent from keeping up with inflation for many years. This question is raised frequently in our chat room at High Yield Landlord. It would seem that this should reduce property values and thus drive up cap rates.

To look at this, I valued a property based on the following cash flows. Assume a ten-year lease term with a fixed rent to start. This is extreme since nearly all leases have escalators. After that, adjust rent with inflation. For the same three real rates shown, one gets this:

RP Drake

We see that there is an effect, but that for a sustained inflation rate of 5% the impact is only about a 10% change in Cap Rate. The history reviewed above supports this conclusion.

I also modeled a lease that had a fixed escalator of 3% for 20 years before adjusting to match inflation. This is also not uncommon. There again, the cap rate only changed about 10% for an inflation rate of 5%.

The history shown above convincingly torpedoes the point of view that the spread between cap rates and interest rates is causal or even meaningful. This makes sense in the context of the simple models shown above.

So this is where we are. Cap Rates change little and slowly. NOI and Property Values both scale with price inflation.

The Current Madness

Inflation has been quite low for some years now. The recent decline in Cap Rates represents a decline in the real rate investors are willing to accept.

What’s more, in some locations and in some sectors Cap Rates are plummeting to previous unheard of lows for the US. We’ve been hearing for a year or two about Cap Rates in the 3s in some markets for multifamily properties.

But that was nothing. Quoting from this GlobeSt. article regarding Cap Rates:

John Chang, SVP of Marcus & Millichap: “… the demand for large apartment properties, generally those with at least a hundred units, has spread nationwide,” said Chang. In top-tier assets and premier markets, like Austin, Phoenix, parts of Florida, and some other markets were in the mid-to-upper 2% range. Large upper tier properties in other parts of the country were trading at 3% to 4% cap rates.

Large value-add multifamilies and large properties in tertiary markets have also been trading at a premium. Cap rates there ranged from 3.5% to 6%.

With Treasury Rates closing in on 2%, this seems like madness, doesn’t it? You will make almost no profits from operating properties bought at that price.

So is this just investors needing to deploy, at no matter what cost, massive amounts of capital that ultimately exists as a consequence of actions by the Fed? Is the competition for properties perceived as high quality pushing the price down and the real return toward zero? It could be.

It seems to me, though, that operating profit is no longer the point. Investors everywhere are scared to death of inflation.

Property values will increase with inflation because rents and thus NOI will. (See the equation above).

There are qualifications about long leases. But if you do the numbers, as in the example above, the impact is smaller than you might think.

If you are more concerned about preserving the real value of your principal than about generating earnings on it, then you may care little whether you have earnings at all. If you leverage the property investment, inflation will generate gains for you even in the absence of earnings.

Perhaps History is Rhyming

Real rates for real property have varied a lot over time. They were significantly negative in the years near 1980.

That was another period when preserving principal was more important than generating returns for many investors. Because inflation was large, the cap rate stayed high even as real rates were negative.

So both then and now are periods of suppressed Cap Rates and low real returns. Something of a rhyme.

Will Real Cap Rates Go Negative?

This leads one to wonder whether real rates might get pushed below zero, as they were in that prior period. It could happen. Cap Rates are set by supply and demand in the property markets.

To my mind this is unlikely, at least yet. Back near 1980, inflation had been large for many years and clearly was not going away any time soon.

In contrast, while we have had significant price inflation in the US during 2021, the future is very unclear. One can find convincing arguments in both directions, as usual.

It seems a bit early to me to get out the panic button and drive real rates negative. Time will tell what actually happens.

Takeaways

One sees some amazing claims about what inflation will do to property values. Some commenters on SA argue that property values will collapse and so will REIT stock prices.

But long initial leases have only a limited impact on property values. This is especially true if they have escalators capped near 3%, as most long-term REIT leases do.

The present article has substantially disproven assertions that we can expect property values to collapse. History shows remarkably small changes in average cap rates. Theory supports this.

For property values to collapse the real rates of return demanded by investors would have to move up sharply. That would not happen quickly, and it seems that continued declines of real rates are more likely.

Regarding the questions asked at the start of the article, the recent declines in REIT stock pricing appear to have created improved investment opportunity. This does not guarantee that those prices won’t fall further; but the market will eventually come to understand the value story and to reflect real value. I’m certainly not selling my REITs out of concern for inflation.

Be the first to comment