Sean Gallup/Getty Images News

The Western Union Company (NYSE:WU) is one of the most storied companies in financial services. For decades, it was synonymous with money transfers. Yet, since its debut on public markets in 2006, the stock price has been flat. The company is cheaper than ever, but this attractive valuation has a reason: Western Union no longer has a moat. As competition increases, the reality is that lots of companies can do what Western Union does. The company’s very success locks it away from being able to disrupt itself into the company it needs to be to succeed in the new age. Investors should get out.

Shareholders Have Not Been Rewarded For Sticking With Western Union

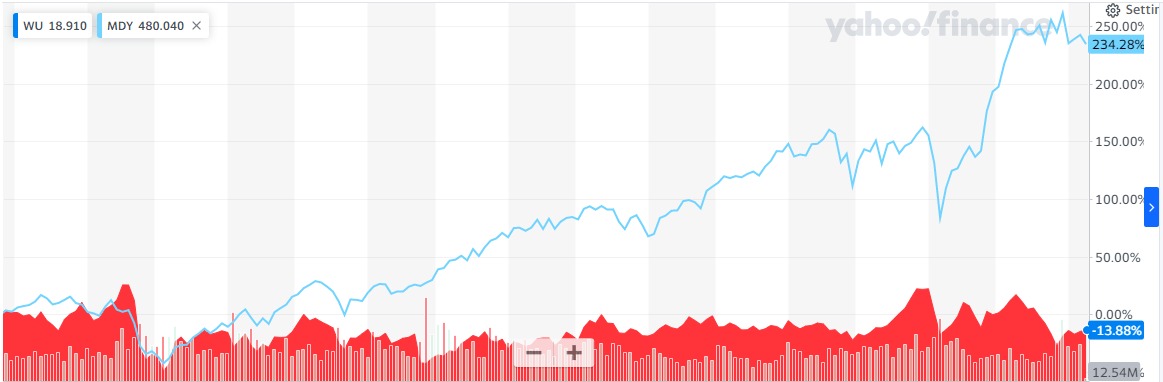

Western Union spun off from First Data and began trading on public markets on October 2, 2006. In the annual report for that year, then president and chief executive officer, Christina Gold, ended the financial year speaking about how Western Union was “incredibly fortunate to have begun our life as an independent public company with strong financial performance and a leading position in a thriving global business.” She spoke about the underserved parts of the world, and “ambitious targets for the immediate future, like increasing our presence and market position in rapidly growing markets like Asia, the Middle East and India, and expanding our C2B segment outside of the U.S.” Since then, the company’s stock market performance has been a tale of woe. Western Union closed its first day on public markets on October 2, 2006,with a share price of $19.76. Today, it trades at around $19 per share. Since listing, the company has delivered 2.53% annualized total returns to shareholders. The last decade has seen some improvement, with investors receiving a 4.15% annualized total return, compared to 12.15% for the S&P MidCap 400 (MDY).

Source: Yahoo! Finance

A shareholder holding the stock since listing would have lost 0.19% per year in compounded returns. The company’s underperformance has continued even though management has shrunk the number of fully diluted shares by nearly 40% since its spin off. As the total return performance shows, increasing dividends from $0.04 per share in 2006 to $0.94 per share in 2022 (for a dividend yield of around 5%), has not saved investors.

Western Union is cheap. The stock is trading at a price/earnings (PE) ratio of 9.57, compared to its 5-year PE ratio of 17.48. The company’s price/forward earnings multiple is 20.67 compared to a 5-year average of 10.76. Its enterprise value/EBIT is 8.77 compared to a 5-year average of 11.38. And, here’s the kicker, the company’s underlying business has actually improved: since 2012, the company has improved returns on invested capital (ROIC) from over 24% to just over 26% in 2021. Double digit is top tier.

As much as Google is synonymous with search, in many parts of the world, making cross-border payments is associated with Western Union. Remittances performed well in 2020, falling by just 1.7% despite doomsday warnings due to the pandemic. According to the World Bank, remittances grew by 7.3% in 2021 and are forecast to continue to grow in 2022. This nearly $600 billion market is up for grabs. Western Union’s economics look sound and they operate in a growing and vast sector.

Superficially, Western Union meets all the criteria for a wonderful business trading at a discount to value. So, what’s wrong? Western Union is a value trap. The company’s financial performance hints at why Western Union is trading so cheaply. Since 2006, revenue has grown by a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of just over 2%, from nearly $3.7 billion in 2006, to over $5 billion in 2021. Net income has declined from $914 million in 2006, to nearly $806 million in 2021, compounded at -0.84%. Earnings per share (EPS) have grown from $1.20 in 2006, to $1.98 in 2021, compounding at 3.39%. Investing in Western Union has been an exercise in treading water.

The Case Of The Disappearing Moat

Stereotypically, disruption is about an old, jaded giant that allows its younger, more fleet-footed rivals to topple it with daring innovations. The reality is that disruption is much more subtle than that. Many people who talk about the disruptive impact of Apple’s (AAPL) release of the first iPhone ignore the fact that Research in Motion’s best years were after the release of the iPhone. Disrupted firms are not run by incompetent people. Sometimes, their very success locks them into decisions that make it difficult to react to new innovations, as happened with Kodak. We have to combine Clayton Christensen’s disruption theory with Hamilton Helmer’s theory of counter-positioning. Western Union’s struggles are because it cannot adequately respond to disruptive threats not in spite of, but because of its competencies and historical success. Simply put, counter-positioning implies that the costs and risks of Western Union disrupting itself to win the vast, growing market in money transfers, particularly in remittances, are so high that Western Union cannot adequately react.

Western Union is led by smart people who understand the need to update the company. The company has made the right changes to respond to digital transformation and growing demand. It has grown its digital money transfer business, which contributed 8% of consumer-to-consumer (C2C) revenue (which makes up the bulk of revenue) in 2016, to 24% in 2021, according to the company’s 2021 annual report. In 2021, Western Union’s digital business passed the $1 billion mark, growing by 22% year-over-year, as the company continued to grow its digital business and expand its retail offering. The company’s new president, CEO and director, Devin B. McGranahan has spoken about how Western Union has expanded its digital and retail partnerships, created a multi-currency digital wallet and digital banking platforms in key countries, and seeks to become a “valued financial partner” for customers everywhere. The issue is not that Western Union is not innovative, it is that its business model has locked it into a path that is leading toward disruption.

Western Union used to be the only game in town, along with MoneyGram (MGI) and banks. For the unbanked, or to send remittances to countries outside the core of the world system, Western Union and MoneyGram were the primary solutions. Readers from the developing world will understand that there was a time when a person would “MoneyGram” you, or where making cross-border money transfers meant going to Western Union.

Competition is killing Western Union. The rise of tech giants with massive cash hoards and a desire to deploy them in profitable ventures, has seen competition increase. Meta (FB), Alphabet (GOOG) (GOOGL) both offer money transfer solutions. You can send money on Block’s (SQ) CashApp, with PayPal (PYPL), on Zelle, with Xoom, OFX, Wise, and even retail solutions such as Walmart’s (WMT) Walmart2Walmart, and even with crypto, among other solutions. Alibaba (BABA) and other Asian tech firms offer money transfer solutions. Today, competition is not just about direct peers, Western Union has to worry that Big Tech may offer money transfer solutions. It has to worry about fintech companies, unencumbered by legacy systems, offering better solutions. Bank consolidation in the United States, as well as globally, has made it easier to transfer money. Across the European Union (EU), intra-EU payments take less than 24 hours, often less, thanks to the single euro payments area (SEPA) regulations. Today, money transfers are no longer synonymous with Western Union and its old rival, MoneyGram.

As Ben Evans has argued, losing a moat happens, not because of antitrust measures, or even decisions taken by a company. A moat can disappear simply because the business stops being the center of its industry. This is why Western Union can simultaneously improve ROIC, while struggling to grow, and facing declining profitability, at a time when international money transfers are growing. If so, many businesses can offer money transfer solutions, then by definition, Western Union does not have a moat. Whether you’re in South America, Africa or Asia, there exist a myriad of solutions to sending money and those alternatives are growing.

Conclusion

Investors should not be fooled by Western Union’s attractive valuation and pedigree. The company is aware of the pressing need to transform itself for the digital age and get closer to its customers, but it is counter-positioned away from disrupting itself into the firm it needs to be to succeed in this new environment. The company’s stock price performance tells us everything. Western Union is cheaper than ever, and that’s because the market is right: Western Union no longer has a moat. Investors in the company need to sell.

Be the first to comment