Ivan-balvan/iStock via Getty Images

Investment Thesis

I have been bullish on Viatris (NASDAQ:VTRS) stock in several previous notes for Seeking Alpha, including during the time when the company – formed via a merger between Pfizer’s spun out Upjohn legacy brands division and generic drug giant Mylan – still counted its biologics business division as part of the company.

As most investors will know, in April, Viatris elected to sell the biosimilars division to Indian Pharma Biocon in a $3.3bn deal – a decision that saw its share price fall by >30% overnight, from $14.5, to $10. Biosimilars was arguably one of the more progressive areas of Viatris’ business – an area capable of growth, to offset the inevitable declines in sales of Pfizer’s legacy assets.

As disappointing as the decision was – and the transaction is expected to close before the end of the year now that antitrust clearances have been negotiated in the US and India – Viatris does retain a 13% stake in Biocon, having received $2bn in cash, with another $335m pledged to be paid in 2024, and the remaining $1bn in compulsorily convertible preference shares.

Viatris stock looks attractive based on several factors. The company is forecasting for revenues of $16.2bn – $16.7bn in FY22, adjusted EBITDA of $5.8bn – $6.2bn, and free cash flow of $2.5 – $2.9bn.

If we treat free cash flow as net income, we can estimate a forward earnings per share (“EPS”) figure of ~$2.2, and a forward price to earnings (“PE’) ratio of ~4.75x. A low PE ratio often suggests that a business is thriving and its valuation will rise. Presently, Viatris’ market cap valuation is $13bn, meaning its forward price to sales ratio is <1x, which again, in ordinary circumstances, hints at a company being undervalued.

Viatris also pays a dividend – $0.12 this quarter, providing a yield of ~4.5% at current share price. Management’s stated ambition is to ensure that the dividend remains above 25% of free cash flow generated.

On the negative side, we know that Viatris’ revenues are likely to shrink year-on-year as sales of legacy brands such as Lipitor, Lyrica, EpiPen and others decline in the face of generic competition and new drug launches. We also know that Viatris has a high level of debt – as of Q2 2022, the current portion of long term debt was $768m, and the long term debt itself stood at $19.2bn.

Since Q420, Viatris has reduced its debt from $25.1bn, to $20.4bn (according to its Q222 earnings presentation), and its gross leverage from 3.7x, to 3.3x. $1.5bn of debt was paid down in H122, and management has also pledged to complete a $1bn share buyback program, which is another fillip for investors on top of the dividend.

Even so, most companies have debt because they have invested heavily in R&D and are expecting top line revenues to grow as a result, but Viatris does not have this luxury.

It hasn’t invested $25bn in new product development, it has inherited $25bn of debt. As good a drug as Lipitor once was – over the cholesterol lowering drugs’ lifetime it has generated revenues of >$125bn, making it one of the most successful pharmaceutical products ever – its sales are not going to start climbing again.

Heavily in debt, its most promising division sold off, and with falling sales, Viatris may be undervalued relative to what it is achieving today, but what is worrying the market is what it may be achieving tomorrow. So how does management persuade the market otherwise?

It is simple really. Management needs to restore belief in its products and their sales potential, ensure that the company maintains or ideally increases its profitability, and create a pipeline that investors can get excited about.

The alternative scenario is that management simply let things slide, banking the profits generated by legacy assets and using it pay off debt – and pay themselves. Let’s look at each part of the Product / Profit / Pipeline trifecta in more detail.

Products

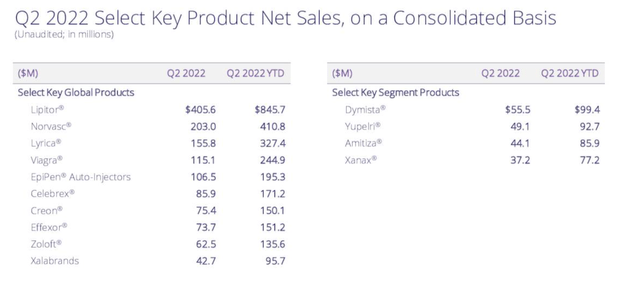

In Q222, Viatris drove net sales of $4.1bn – down 10% year-on-year. Brands accounted for $2.48bn, or ~60% of revenues, Complex Gx and Biosimilars $355m, or ~9%, and generics accounted for $1.27bn, or 31%. Worryingly, the generics division revenues were down 17% year-on-year, whilst brands were down 8%.

Generics is a section of the business derived from Mylan, and one that I would have expected to be growing, but it is shrinking, and nowhere more so than in emerging markets, a potentially fertile market for generics – sales were down 42% year-on-year in this market however.

Viatris sales by drug Q222 (Viatris)

With sales of generics and brands falling, and biosimilars being sold off, it seems clear that Viatris presently has no growth prospects. It is almost behaving like a store holding a closing down sale.

Profitability

Shrinking top line revenues does not necessarily make a business a bad one. Mostly, it depends on profitability, and Viatris delivered free cash flow of $719m in Q222 – a net margin of 18%, which is impressive. FCF across H122 is even better – $1.79bn – up 41% year-on-year – for a margin >21%.

Looked at in the context of debt, however, Viatris has generated $4.3bn of free cash flow over the past 6 quarters, enough to pay off ~17% of its debt. It will be 5 long years before Viatris can say that it is close to eradicating the level of debt it inherited, so investors should not hold out too much hope of raised dividends and expansive share buyback programs, particularly when each passing year results in a decreased top-line contribution.

Currency headwinds have forced management to reduce its FY22 revenue guidance, from $17bn – $17.5bn, to $16.2 – $16.7bn. Viatris does most of its business overseas – but I would be more concerned about whether Viatris is truly a company with global ambitions. That was the dream that was sold to investors in detailed March 2021 investor day presentation – there was talk of establishing a “new kind of pharmaceutical company” but the company seems to have had its wings trimmed significantly since those hopeful days.

The interesting question to answer is when falling top line revenues becomes a problem for a company like Viatris. $16.5bn of revenues and a 25% profit margin is arguably better than $20bn of revenues and a 15% margin, but when does a lack of growth become a problem? With a float of >1.25bn shares, investors are almost certain to feel the pinch at some point, and sizeable profit margins may not appease them when net income is declining every year.

On the Q222 earnings call, management made it clear that it was lining up another sale of part of the business – it’s not clear what yet, but investors may possibly have to brace themselves for another M&A deal that negatively impacts the share price.

Pipeline

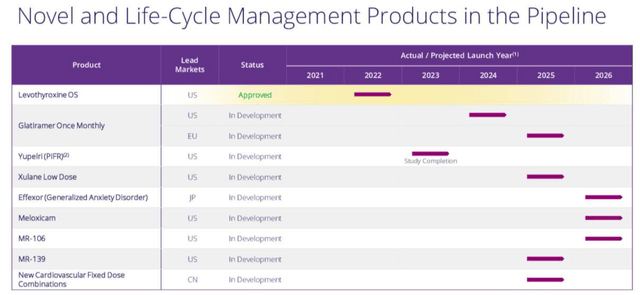

In the near term, Viatris’ pipeline does not instill great confidence that declining sales of legacy brands can be offset by the emergence of new drug products. A Levothyroxine generic has recently won approval, with a total addressable market of ~$4 – $5bn, of which it will likely only claim a very minor share.

As we can see above, however, the next approval is not due until 2024, for a Multiple Sclerosis generic, a version of Teva Pharmaceuticals Copaxone, which itself faces some stiff competition. Sales >$500m would likely be miraculous. Things seem to pick up in 2025 and 2026, but investors should be aware of the twin threats of the time value of money, and the high rates of failure associated with the drug trial process, even in the case of generics.

In short, Viatris has a pipeline, but whether it is enough to win over investors is debate-able. It looks a little thin, and a better question may be whether it is even winning over Viatris management?

Conclusion: What Exactly Are Investors Buying?

Viatris comes across as a company that is praying for a Benjamin Button style existence to me. It markets and sells a host of once-great, but now ageing assets, such as Viagra, Lyrica, and Lipitor, whose heydays will never return, but whose comparatively meagre earnings can be used to pay off the debts accumulated by Pfizer and Mylan before the 2 companies engineered this merger.

At first, management appeared to be dedicated to establishing Viatris as a generics and biosimilar drug manufacturer and marketer of global significance, but perhaps it has all proven to be too difficult. Developing a portfolio of <$500m p.a. selling assets must seem like small potatoes when you have Lipitor and Viagra in your stable. Viatris seems to have reinvented itself as a luxurious retirement home for ex-blockbusters.

There must come a topping point when investors stop admiring management’s ability to pay down debt, engineer share buybacks, and offer a dividend, and begin to wonder how they will get their money back when revenues are falling year-by-year – there must come a day when there is not enough revenue to go round.

That is not necessarily management’s problem, but investors who expected to see an exciting new biosimilars player emerge from the ashes of yesteryear’s blockbusters may end up disappointed and out of pocket.

Any company that wants to be successful in the long term needs to have a growth plan, but it is tricky to discern precisely what that plan is in the case of Viatris.

Mylan’s management team were known for prioritizing their own pay packets over running a successful enterprise. I haven’t given up on Viatris yet, but I wonder how much worse things need to get before they begin to look better? It could be a bumpy ride, but that would be preferable to an incremental slide.

Be the first to comment