Jozsef Soos/iStock Editorial via Getty Images

United Airlines (NASDAQ:UAL) was hit hard in February 2021 when the FAA grounded Boeing 777 jets with Pratt & Whitney engines. Given the global fight against the pandemic, which kept international travel down, this provided some headwind to United Airlines, but the impact was not as big as it would have been under normal circumstances. That is also why with air travel demand picking up again and international travel rules easing bringing back the Boeing 777 in a safe and timely manner was important. In May 2022, the FAA cleared the aircraft again for commercial service which set a mechanism in motion for United Airlines to start returning the Pratt & Whitney powered Boeing 777 fleet.

In a previous report, I analyzed the progress of the return to service for United’s subfleet. We are now three months later and I want to revisit the subject and comment on how the return to service is a good thing but there have been challenges and there will be more challenges in the future.

The Flight That Grounded The Boeing 777

So, let’s first discuss why the subfleet of the Boeing 777s was grounded in the first place. In February 2021, shortly after departure from Denver for Honolulu, United Airlines Flight 328 suffered an uncontained engine failure resulting in a fire in the right engine and significant damage to the nacelle. The flight crew was able to safely return to Denver with no injuries reported. Following the incident, Boeing (BA) adviced Boeing 777s powered by Pratt & Whitney engines to be grounded and agencies around the world including the FAA indeed grounded the airplane with the particular type of engines.

The problems can be traced back to the blades, which are manufactured using hollow blade technology which is a signature of Pratt & Whitney to reduce the total fan weight. However, these blades suffer from fatigue earlier than expected meaning that cracks propagate faster than initially anticipated. The fix for this is relatively straightforward because inspection intervals can be reduced. However, this will result in higher maintenance costs and the non-destructive inspection method, Thermal Acoustic Imaging or TAI, requires advanced equipment and training. Simultaneously, Boeing had already been working on redesigning the nacelle to make it more robust following similar incidents in 2018 and 2020.

United Airlines Wide Body Capacity Tumbles 25% Overnight

For United Airlines, the hit was bigger than for its peers as 52 aircraft compromising 25% of its wide body fleet was affected. Delta Air Lines (DAL) and American Airlines (AAL) were not affected because both airlines used the Rolls Royce Trent series turbofans on their Boeing 777-200/200ER fleet and Delta Air Lines had already eliminated its fleet of Boeing 777-200ER aircraft as part of its fleet transformation that was accelerated during the pandemic. So, for United Airlines the big question was whether the airline could bring back the subfleet back to commercial service fast enough to benefit from the strong recovery in air travel demand. This was further amplified by United Airlines considering the Boeing 777s their most efficient fleet member as measured by cost per available seat-mile and their cargo capacity makes the aircraft strong performers in the airline’s fleet, which should provide additions to the company’s top line as well as a reduction in unit costs.

United Airlines claimed that the grounded fleet represented 10% of its total capacity and independent calculations I performed modelling the Boeing 777 fleet as an aircraft with a daily utilization of 11 hours, derived from flight data, showed that the subfleet represented 10.3% of the capacity.

A Fast Return

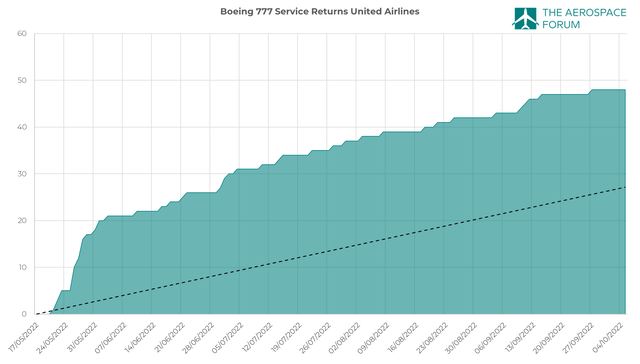

Boeing 777 re-entry trajectory United Airlines (The Aerospace Forum)

Earlier United Airlines signalled that it would take up to nine months before all airplanes would be able to return to service. It seems that the airline made a back-of-the-envelope calculations using the limited Thermal Acoustic Imaging capacity. Each blade requires 8 hours for inspection and each turbofan has 22 blades. TAI capacity is limited to slightly over 250 blades per month meaning that per month the blades of six aircraft could be inspected. With 52 aircraft in the fleet that brings the expected time to return to service to nine months as shown in Figure 1 with the black dotted line. In total, the inspections by estimates of the FAA would cost at least $620,000.

However, after a deep dive analysis of the data it was found that United Airlines returned the aircraft much faster to service than capacity and its own estimates would suggest. The reason most likely is that United Airlines started shipping blades to Pratt & Whitney for inspections at an early stage allowing the airline to quickly return the aircraft to service when all changes dictated by the FAA were made. By now, 48 out of the 52 aircraft have returned to service while the linear trend would suggest that by now only 27 aircraft would have returned.

In total, data analytics from the The Aerospace Forum observed 7,955 flights with a total of 41,214 flight hours and a capacity of 6.2 billion seat-miles since the return to service. Currently, four aircraft have yet to return. One aircraft is in Victorville, one flew to San Francisco on the 23rd of September and two other aircraft have been flown to Xiamen and Hong Kong likely for more elaborate maintenance activities.

Not A Smooth Ride Back

While the return to service has been faster than the linear trend would suggest, the return has not been smooth. On the second of September, a Boeing 777-200ER with registration N787UA had to abort its take off at Amsterdam Schiphol Airport due to smoke in the cabin. The aircraft left Amsterdam on the fifth of September, but on a flight from Newark to Sao Paulo sparks were seen coming from the engine. After a correction to the hydraulic system, the aircraft was returned to service on the 21st of September. One thing that should be noted is that both incidents occurred on a single airplane, and therefore do not necessarily say something about the fleet. However, two days later, United Airlines was forced to cancel flights as it found out required inspections on the leading edge slats of 25 aircraft had not been carried out.

Time for a replacement

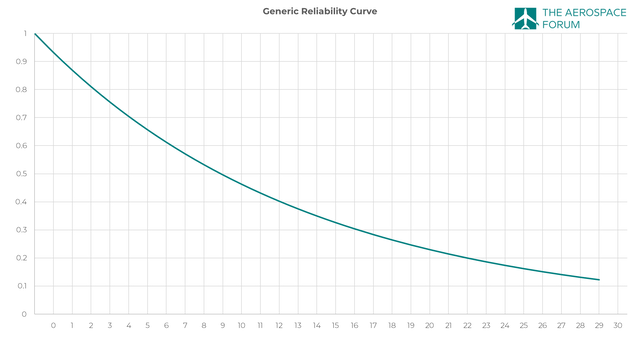

Generic reliability curve (The Aerospace Forum)

The events themselves do not necessarily indicate that there is a major problem. However, the issues with N787UA while isolated do show that over time an aircraft becomes less reliable as it ages and requires more maintenance and downtime, including unscheduled downtime. In reliability engineering, the reliability of a product is described by the product of the reliability of all parts and the reliability of each part is calculated based on the exponent of an inversed assumed failure rate multiplied by time. Figure 2 shows a qualitative reliability curve, and unsurprisingly the reliability comes down as the aircraft ages. Components can be swapped out to improve reliability, but overall the reliability of an aircraft decreases as it ages requiring more costly maintenance to uphold reliability, making it financially less appealing to operate these jets.

The 52 jets that were taken out of services have an average age of 24.2 years, and the oldest one is over 28 years old. Typically, airlines replace the aircraft when the aircraft is 25 to 30 years old. What we see at United is that because the company has opted to postpone deliveries of the Airbus A350, the company is operating an aging less fuel efficient fleet while companies such as Delta Air Lines and American Airlines have already started to renew their fleets, and it shows in the average age of the total fleet. United’s stands at 17 years, while American Airlines has a fleet with an average age of 12.3 years and Delta Air Lines has a fleet with an average age of 14.8 years. Saving on costs, United Airlines has been kicking the can down the road, but the reality is that in two years United Airlines should start replacing its aging fleet members in the Boeing 777 subfleet. The company has a dormant order for the Airbus A350, and it has a handful of Dreamliner orders. These aircraft could be used to replace the Boeing 777-200/200ER fleet, but it means that United Airlines is looking at CapEx of $8 billion to $9 billion to renew the fleet. Usually this is financed with debt and with interests rates higher, that could become costly for United Airlines while the competition is progressing better in keeping the fleet age down.

So, United Airlines can point at the Boeing 777 as a CASM winner, but the reality is that the Boeing 777-200/200ER is less fuel efficient and the fact it is a CASM winner comes primarily from the aircraft likely being fully depreciated and having these aircraft fly further away with a high number of seats. In a competitive environment, airlines that have the Dreamliner and the Airbus A350 are positioned much better to compete in a cost-efficient way.

Conclusion: Wide Body Renewal Might Make United Airlines Stock Less Desirable

United Airlines is likely happy with the fast return to service for its fleet of Boeing 777-200/200ER aircraft. However, that return has not been without issues and also reflects the need to seriously consider fleet renewal options. While other airlines have already renewed, United Airlines has not done that with its wide body fleet, and as a result, the company has a significantly older and less fuel efficient fleet to compete with its peers. So, United Airlines has no choice other than either reviving its dormant order for the Airbus A350 or acquire more Dreamliners; both come at a cost of $8 billion to $9 billion which will give the company an additional debt load and interest expense, and pointing at lower CASM numbers is not going to change anything to that reality.

Be the first to comment