sturti/iStock via Getty Images

I bought my first shares of corporate stock sometime back around 1998 or 1999. At the time I owned nothing besides U.S. Treasuries, money market funds and multiple equity mutual funds. I had been playing around with a relatively new invention – the online stock screener – which is how I discovered Canadian National Railway (CNI). But it was cumbersome to buy those shares because I was an attorney and needed to clear my initial investment in advance through the firm’s conflicts committee. Thanks to that hassle factor, I resolved to hold the stock more or less permanently. Over time, I added new positions one-by-one to my individual stock portfolio and what I see now (but didn’t know then) is that I was building a passive, long-term stock index fund.

As the years went by, I gradually cycled my portfolio almost entirely into individual shares. Suffice it to say that I didn’t build my own DIY passive index fund in the most efficient way possible. I would have saved myself YEARS of effort (and probably earned higher returns) if I’d simply known ahead of time that my ultimate goal was to build a passive index fund that pays steady and rising passive income that exceeds my living expenses.

So if that end goal sounds similar to yours and you’re less open to wasting your time than I was open to wasting mine, here’s a list of the top three things that I would and would not do differently if I had to start over again from scratch.

I Would Start By Skimming the Top 25 or 30 Stocks From Commercially-Available Passive Dividend Growth ETFs. Then I Would Slowly and Sparingly Add Positions From There

My first mistake: I own 71 different stocks. At one time or another, I have researched all of the companies that I own and I stay modestly up to date by reading news and financial statements for some of them. Most of that effort has created little to no financial value (although the work was enjoyable and educational). The reason why I say that hand-selecting 71 stocks was a waste of time is because the overwhelming bulk of my portfolio returns comes from the largest 25 or 30 positions that I’ve held for the longest time (which account for 60% to 70% of my entire portfolio).

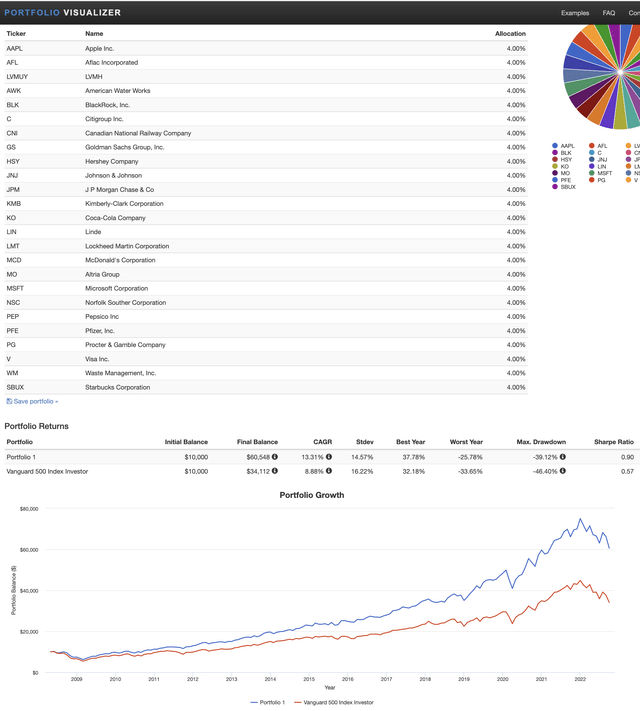

Here is the long-term performance on my 25 largest and longest-held positions – many of which I could have simply lifted straight out of the published portfolio holdings for the Schwab U.S. Dividend Equity ETF (SCHD), or the Vanguard Dividend Appreciation ETF (VIG). According to PortfolioVisualizer.com, if I’d simply bought only these 25 shares in equal proportions, held the stock and reinvested the dividends, my portfolio would be up 13.31% per year over the past 15 years compared to 8.81% for the S&P 500. And here is the key takeaway: the remaining 46 positions that I own have neither added to nor subtracted much from my overall portfolio returns. So the question becomes…. why own them?

My Top 25 Portfolio Holdings (Portfoliovisualizer.com)

Rational conclusion: Spending years researching and adding dividend growth companies piecemeal to my portfolio did little to increase my returns. I could have done at least as well (or maybe better) by simply purchasing 25, 30 or maybe 40 of the top positions from one or two dividend growth index funds, ensuring the positions are diversified across industries, buying the positions all at once and then adding capital to those positions over time. In my case, I’d probably screen out any companies with lower than a BBB+ credit rating, profit margins below 10% or a P/E ratio above 30 (it’s anyone’s guess whether those factors would or would not increase returns or lower risk, but they’d make me feel more comfortable and therefore less inclined to engage in market timing frolics). The point is that I wouldn’t waste time trying to reinvent the wheel (which is basically what I actually did) – I’d start with a commercially available wheel and doctor it up through a process of subtraction.

One thing that I did get right is that I took my time adding new positions whenever I found truly exceptional businesses that I considered worth owning. Not every stock I own is represented in any dividend growth index (at least none that I am aware of), but I am nevertheless very happy to own shares of companies like Alphabet (GOOG), Amazon (AMZN) and Hermés (OTCPK:HESAY). By the same token, I went way too far adding more positions than made any practical sense (most of which I cannot now sell without triggering value-destroying capital gains). Time and again I have learned that any position smaller than 2% of my overall portfolio will never move the needle… and what other justification could there be besides that for owning the stock?

I Would Mindlessly And Frequently Reinvest Dividends Irrespective of Any Predictions

The best investment advice that I ever gave myself (and that I wish I’d followed more consistently) is to act EXCLUSIVELY on the basis of what I can and do know, and to ignore the rest. For instance, I can’t possibly predict the future any better than the entire global securities market can. By contrast, I can and do know when I have extra cash that I probably don’t need for spending purposes. I can’t possibly know whether my portfolio will be up, down, or sideways this year, next year, or even ten years from now. By contrast, I can and do know that if I use income to buy more income-generating assets, my income will probably grow exponentially over time.

Rational conclusion: The two things that I can and do know and the two things that I cannot possibly know coalesce into one logical course of action. I should only and always buy stocks whenever I had spare cash on hand, sell stocks only when I need the cash for spending purposes, and otherwise take no action whatsoever. When I do then it can only mean one thing: I am violating my own self-imposed investment mandate (and being the slow learner that I am, I do seem to do that from time to time).

My big mistakes: Over the years, I sometimes sold securities because I thought the price was too high or that it was otherwise likely to fall. As far as the outcome goes for all of those aforementioned efforts, the best case scenario is that the gains I missed out on due to my incorrect guesses cancel out the losses I avoided from my correct guesses. If so, then all of my time and effort selling stocks at “opportune” moments throughout the past twenty-plus years was merely a complete waste of time and energy.

Ahhhh….. but then there is the less comfortable “other case” scenario. I am specifically thinking about those 1,000% gains that followed after I sold my Microsoft (MSFT) shares the first time, and now wondering whether I have ever avoided any 1,000% loss by selling stocks at the right moment.

One might be forgiven if one is now growing dubious regarding the “best case” scenario highlighted in the second-to-antecedent paragraph.

I’m not proud. I’ll be the first to tell you that my broader market timing moves (blessedly few and far between as they are) were a total waste of effort and time. For example, during the financial crisis of 2009, I sold out of many positions because I thought the stock market was going to keep crashing. And by golly I was correct! But then I sat around biting my nails for a couple of months trying to guess when to reinvest back into the market, missed the bottom of the market, tepidly edged back into the churning market waters one toe at a time and in the end, I probably saved myself literally no money whatsoever compared to where I’d be had I sat on my hands. All in spite of my feverish and research-intensive attempts to outguess the global securities market.

Some of you might point out that my lackluster attempt to outflank the stock market during the financial crisis was just plain stupid. But there is a backstory! When my wife and I sold our first apartment, we invested the cash into a handful of stocks and index funds almost exactly at the bottom of the market right after the internet bubble burst. That very fortunate stroke of investment timing produced fantastic long-term returns. Can it really come as a complete surprise that on some level I ascribed our post internet bubble performance to “success” rather than “dumb luck?”

Funny how yesterday’s illusions of “success” can translate into the stern realities of tomorrow’s folly.

The key thing that my DIY passive stock index has taught me is that there is only one way for a below-average investor to earn above-average returns: stay out of your own way and never mistake good fortune for savvy. Investing money is a lot like singing in public: wanting to be good at it is not the same thing as being good at it, and for most of us, the less often we do it the better off we will be.

I Would Never Rebalance

I can’t possibly predict whether any given individual stock will rise or fall either in the near-term or in the long-term. I can and do know that if I own 25 or 30 stocks, there is a reasonable chance that one or maybe two of them will deliver exceptional long-term returns while all the rest deliver average to mediocre returns. And there’s catch: I can’t possibly know ahead of time which (if any) of those companies will ultimately turn out to be the best performer(s) over the very long-term.

But by the same token, I can and do know that if and to the extent I ever sell my shares in that (or those) companies, it (or they) will not deliver ANY long-term returns to me.

My mistakes: I can and do know that diversified portfolios are less risky than concentrated portfolios – particularly for someone like me who has no unique insights, abilities or access to information. Reasonably enough, I would sometimes prune capital out of my largest winning positions and reallocate it into my losing positions to keep my portfolio somewhat in balance. I always figured that every stock in my portfolio has an equal chance of rising the most in the future.

That was wrong. What I’ve found is that some companies I own have delivered far superior performance for one simple reason: they are better managed and sell superior products and services at superior profit margins. It is a rare thing to stumble upon a company like that and if you do, you’ll probably end up earning above-average risk-adjusted returns on your investment. But here is the key question to ask: how do you know whether the potential value of those higher risk-adjusted returns exceeds the potential value of diversification? The answer is you can’t.

And THAT was my mistake. Since my plan was always to act only on the basis of information that I can and do know, I should never have sold a single one of my top-performing stocks simply to diversify my holdings. Each time I did, I had no clue whether the value of what I gained was greater than or less than the value of what I gave up. No wonder rebalancing didn’t work particularly well for me.

Rational solution: I’m now resolved to never rebalance. If I had to start over again with a new DIY dividend index fund, my goal would be to start out with a balanced and diversified portfolio and in the best case end up with a portfolio that is concentrated in one or two areas. By never rebalancing, I’d assume that the worst case would be that I’d end up exactly where I’d started – with a balanced and diversified portfolio… which sounds sort of like a win/win.

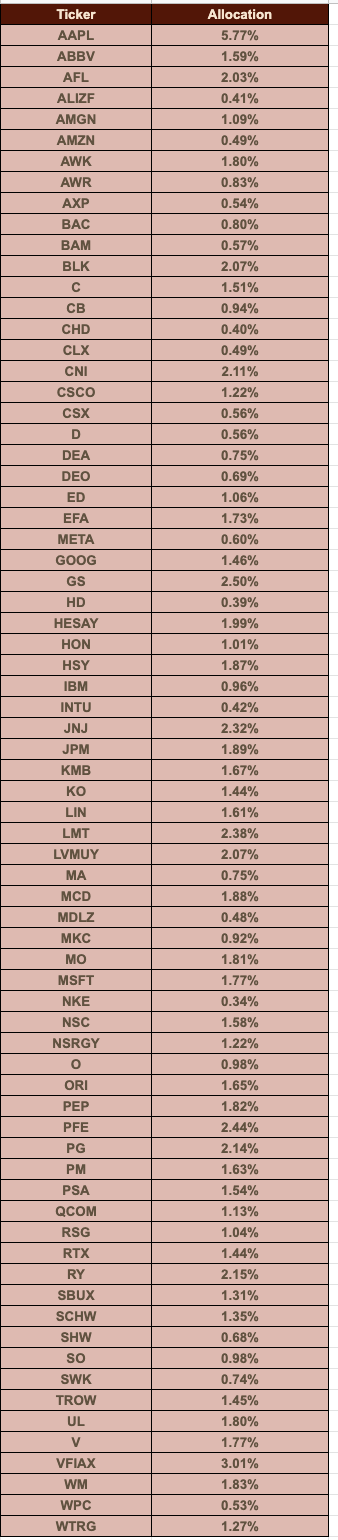

Disclosure: I always feel that it is good practice to disclose any possible financial bias that I might have. For that reason (and for only that reason), here is a list of every security I own and the portfolio percentage that such securities comprise.

My complete portfolio (Author’s personal spreadsheet)

Be the first to comment