cemagraphics

“The world doesn’t work like that.”

So said Zoltan Pozsar recently, about the idea that containing inflation is as simple as central banks hiking rates and shrinking their balance sheets.

His remarks amounted to a recap of missives penned over the past eight months, and although I most assuredly don’t agree with Pozsar all, or even most, of the time, I’m glad he’s adamant about the risk of inflation becoming stochastic going forward.

“In a stochastic world — where the price of everything is thrown around randomly by a pandemic and an unrestricted economic war — inflation is impossible to forecast,” he wrote in early August.

We’re all reluctant to admit that. At the least, we all pretend that in an absolute worst-case scenario, central banks can still control inflation by destroying every last vestige of demand. But that simply isn’t true. There will always be some demand. But there needn’t always be some supply. Sometimes, there may be no supply at all. Just ask the Nord Stream. As such, there’s no guarantee that central banks, no matter how hawkish, can everywhere and always contain price growth.

The Fed and its many critics have at least one thing in common: They both believe monetary policy can be an effective check on inflation.

Critics rarely charge that central banks are incapable of reining in runaway price growth in developed economies. Rather, the derision over the last 18 months centered on the contention that policymakers were, at best, hopelessly behind the curve and, at worst, deliberately behind the curve by virtue of various “shadow mandates.” Either way, policy was derelict, not defenseless. Hapless not helpless.

By contrast, I’ve suggested that, in fact, there’s no guarantee central banks can “always and everywhere” (to hijack a portion of Milton Friedman’s famous axiom) bring inflation under control. If there’s not enough food to eat or oil to go around or if we lack the wherewithal to get the food where it needs to go or the refining capacity to process the oil, then we have problems central banks can’t solve.

Theoretically, central banks can solve such problems by engineering a drop in demand commensurate with constrained supply, thereby balancing the equation. In practice, that’s a questionable proposition in the presence of persistent and severe supply disruptions.

Central banks’ capacity to ameliorate inflation is contingent on two things: Some semblance of adequate supply (e.g., enough food to go around such that loaves of bread aren’t subject to bidding wars and enough labor such that employers aren’t compelled to offer C-suite compensation packages to every new hire, as nice as that’d be) and anchored consumer expectations. If supply is insufficient even in the face of severely curtailed demand and/or if the public adopts an inflationary mindset, central banks will do well just to keep the situation from spiraling totally out of control.

From my perspective, that’s the most damning critique of central banks there is. And yet, so wedded are the Fed’s critics to the notion that central bankers, when they’re not busy being devious, are hopelessly incompetent, that they (critics) miss the opportunity to prosecute the real case. So busy are critics lionizing the likes of Paul Volcker, that they never stop to consider if there’s an even more condemnatory line of criticism. Or maybe they do consider it, but are just too frightened of the implications.

Inflation, as a phenomenon, is independent of central banks and money. It can easily occur in a barter system, for example. In many (or most) hypothetical dystopian scenarios, hyperinflation is inevitable for food and energy. We may currently be living out a kind semi-apocalyptic scenario in which logistical challenges related to supply chain disruptions and war mean that some locales (Europe for energy, emerging markets for grain) are experiencing dystopian hyperinflation. The kind of inflation that’s unresponsive to central banks.

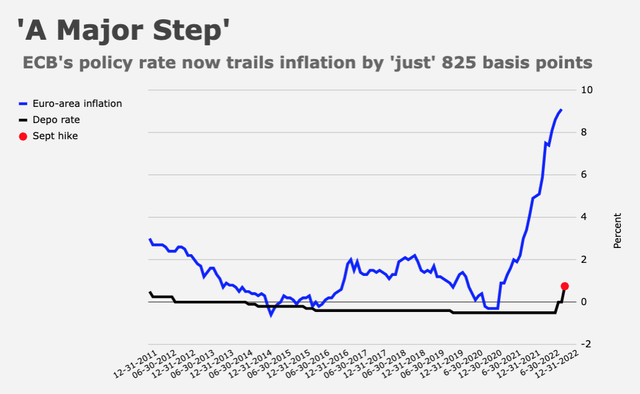

Have a look at the simple figure (below). It’s my contention that inflation in the eurozone is now totally independent of monetary policy. The two aren’t related.

Heisenberg Report

The ECB called this month’s 75bps rate hike “a major step.” I was less generous. Earlier this month, while documenting the decision, I suggested the central bank “has been rendered irrelevant” by war and the bloc’s energy crisis.

We may well be on the cusp of discovering just how true that is. The ECB and the Bank of England are destined to exacerbate economic slowdowns in their respective jurisdictions, and my guess is, any material relief on the inflation front in the UK and the eurozone will come as a result not of incremental demand destruction engineered by monetary policy tinkering, but rather as a result of demand destruction that would’ve happened anyway (due to recessions) and sweeping initiatives aimed at capping energy prices.

“Realistically, given the global nature of the staggering supply shocks, it would’ve been impossible for monetary policy alone to come close to the 2% inflation target from mid-2021 onwards without strongly depressing domestic demand, which may now happen anyway,” Rabobank’s Stefan Koopman and Michael Every wrote, in a note out late last month. “It’s not just global demand imbalances that are driving low or high levels of inflation, but ongoing geopolitical conflict and the weaponization of commodities and supply chains that will last for many years,” they went on to say.

Koopman and Every specifically addressed the BoE’s impossible dilemma, noting that thanks to Brexit and “the lopsided return to business after COVID,” the UK economy has undergone a structural change which entails lower trade volumes, lower productivity, and higher odds of labor unrest. Double-digit inflation “will only fan these flames,” they said.

The annual pace of UK inflation decelerated slightly in August thanks to recent declines in petrol, and Liz Truss’s plan to cap household energy bills will likely prevent inflation from accelerating to what some analysts previously suggested could be 20% early next year.

Nevertheless, the outlook is grim. Koopman and Every captured the crucial point in a single sentence: “These aren’t short-term ‘supply shocks’ that monetary policy can overlook, or which any level of rates can overcome in isolation.” No level of rates can solve this puzzle.

Of course, not doing anything (or cutting rates) could make things materially worse for a number of reasons, not least of which is the potential for the perception of policymaker dereliction to un-anchor inflation expectations.

“Cogent arguments are made that raising rates against this kind of backdrop is economic lunacy, but not raising rates against [double-digit] inflation is total abrogation of central bank responsibility,” Koopman and Every remarked. “One might as well not bother targeting inflation at all.”

They aptly (euphemistically, even) called this central banks’ “structural policy dilemma,” before summarizing the situation as follows:

Pre-COVID, even ultra-low interest rates failed to drive productive private- or public- sector capital investment due to debt overhangs and low wage growth, so there was no strong GDP growth and no ‘healthy’ inflation, only asset price inflation. The central bank response was a growing list of liquidity acronyms to paper over these widening cracks. Now, post-COVID and Ukraine, higher interest rates are unable to deal with soaring supply-side inflation, only push demand lower, which ‘helps’ in the most painful way. As such, the question can be asked: ‘What is central bank inflation targeting good for?’ given it only seems to work in a limited set of geopolitical and macroeconomic circumstances.

That’s a recurring theme in my own writing this year: The notion that what an entire generation came to regard as “normalcy” was in fact a peculiarity — an exceedingly unlikely, but highly fortuitous, turn that found the stars aligning to create the conditions for more predictable macroeconomic outcomes.

Romantic comedies, as a genre, owe their popularity to an oxymoron: Serendipity is no accident. That’s why audiences generally come away feeling better about their own lives or, at the least, more hopeful about the chances of finding happiness. That, of course, is a pleasant fiction. Serendipity is luck. “The Great Moderation” was luck. We mistook it for the new normal. But “normal is war,” as I put it last week, while expounding on the same subject.

Bloomberg’s Vincent Cignarella (who’s been fighting an uphill battle against his MLIV terminal blogger colleagues, virtually all of whom are wedded to some version of the orthodox narrative that says rate hikes are the medicine), underscored some of the above late last week. “The Fed has had loose monetary policy since the financial crisis and there was no inflation,” he said, flatly. “The policy mistakes in hiking from 2016 through 2018 did nothing to alter the course of CPI [and] the current hiking cycle, which was at least a year after CPI popped, will do little on inflation, but it will choke off growth and will have to be reversed.” (Emphasis mine.)

Cignarella put the blame for inflation on fiscal policy, whereas I’m more inclined to cite what, try as I might, I can’t avoid describing as the self-evident notion that when, as Pozsar put it, “the price of everything is thrown around randomly,” inflation is just a kite without a string — condemned to whipping around wildly, and notwithstanding episodic downward spirals, always at risk of being carried away into the wild blue yonder.

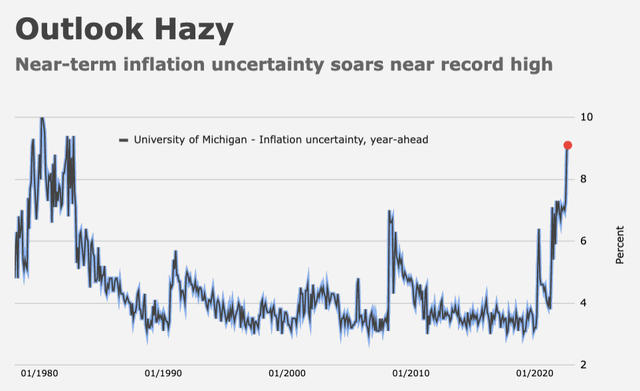

Consumers, at least, realize this, even if economists and central bankers don’t. Inflation uncertainty was the highest since 1982 in the preliminary version of the September University of Michigan sentiment survey (figure below).

Heisenberg Report, University of Michigan

With all of this in mind, it’s becoming more and more difficult for me to countenance boilerplate financial media copy, even as I readily acknowledge that i) the journalists writing it are just doing their jobs and ii) the mainstream narrative is itself just a recitation of economists’ talking points.

This isn’t a belabored (i.e., feigned) lament for “the mainstream.” Or at least not where “the mainstream” is a derogatory nod to some purported link between the financial media and the sort of antagonists you hear about on finance-focused social media, whether it’s the nebulous “establishment” or the nefarious “deep state.” There’s no conspiracy afoot. Nobody is trying to mislead anyone. We should be so lucky. If economists (and the financial media outlets who dutifully paraphrase them) were engaged in a deliberate effort to cover up the fact that, contrary to what we’ve been telling undergrads, MBAs and doctoral students for four decades, inflation isn’t actually something anyone can control, at least that’d suggest the (imaginary) cabal of Davos villains that haunt the dreams of those who frequent popular libertarian doomsday blogs, is internally aware of the problem.

Instead, what we have is a collection of PhDs spanning the political continuum, a community of market participants in whose minds the onset of “The Great Moderation” was contemporaneous with The Book of Genesis, a mail-it-in mentality at mainstream financial media portals and, irony of ironies, a cottage industry of financial bloggers who, in their zeal to lionize “sound money” by advocating for draconian monetary policy and fiscal austerity, remain blissfully unaware of the real doomsday narrative which says inflation is a mostly independent phenomenon that, depending on the circumstances, can’t be checked by any Jays, Janets, or even any “Tall Pauls.”

In the opening line of an article previewing this week’s economic calendar, Bloomberg wrote that “the US Federal Reserve and a number of its global counterparts will launch a rapid-fire attack on inflation in the coming week as their commitment to bringing consumer prices under control gets ever more resolute.”

With apologies, and to quote Pozsar again, “the world doesn’t work like that.”

Be the first to comment