NicoElNino

We are currently in the Jewish New Year period, an auspicious time where one takes stock of one’s own personal journey, where we have come from and where we are going. It is also a time for a new beginning, allowing oneself to close a chapter and begin a new one afresh.

Which is all very well and good, however more often than not, beginnings are hard. “Beginnings suck” I find myself repeating to my kids on a frequent basis, particularly at this time of the year. And so, in the spirit of reflection, I would like to go back to the very beginning; and see if there is anything helpful to convey to someone looking to get over the hump and invest in the market.

Investing can simply be thought of using money to make more money in order to achieve our objective goals. Even before we can talk about portfolio construction and asset allocation, we need to make sure we have:

- A thorough understanding of why we are investing in the first place,

- a basic understanding of how particular asset classes are likely to behave and the extent to which they can be utilized in order to achieve the goal,

- a recognition of the different risks that one may be exposed to, and

- a good understanding of our own emotional makeup.

So let’s jump in.

1. Why is it that we are investing in the first place?

Sounds trivial, but if we don’t have knowledge of our destination, then it is virtually impossible to determine if we have reached our goal, or if we are taking the optimal route.

Am I investing money that will be needed for a known obligation in the foreseeable future? Perhaps I will need it for a down payment on a house. Perhaps I’m saving this money for my kid to go to college in several years. Is this part of an emergency fund that I may need if a crisis crops up? Is this money that I am planning to fund ongoing lifestyle expenses? Is this money that I am saving for retirement many years down the road?

Of course, there is often not one answer. Wealth can be (and should be) split into different buckets. This will allow one to construct a portfolio that will be relevant for each bucket. Once you have determined what it is that you will need this particular money for, then you will be able to move on and ask yourself:

2. Do I have a basic understanding of the asset classes in which I will be investing, and to what extent are they relevant in helping me reach my goal?

If my goal is for a short-term funding necessity, then I need to make jolly well sure that the asset class(es) I intend to invest in will be appropriate for me to reach that goal. I will need to have a thorough understanding of how large a drawdown the asset class can be expected to have, of the expected return and whether it will allow me to meet my funding requirement, of how volatile the asset class is likely to be, and that it’s sufficiently liquid when my funding requirement is due.

Conversely, if my goal is for long term retirement planning, I need to make sure that the asset class can generate the required return and is not constrained by being in too conservative an investment, one whose upside is capped. (Obviously this needs to be determined at the portfolio level, and the portfolio will likely to be constructed so that it includes a range of different asset classes, some which are more aggressive in their nature and some which are more conservative).

Once I know where I want to go to and have mapped out the different routes that will enable me to get there, next I will need to consider the different risks that I am likely to encounter, both in general, and on each specific route.

3. The risks that I am likely to encounter

Common wisdom dictates that there is “no free lunch”. Risk and reward are inherently linked, in that typically the higher the risk encountered, the higher the reward on offer. It’s important to keep in mind that higher risk doesn’t automatically equate to higher returns. The risk-return tradeoff only indicates that higher risk investments have the possibility of higher returns-but there are no guarantees.

Risk is one of the most frequently used words in the world of finance, with a tremendously broad range of meanings with different degrees of relevance to different people, depending upon one’s personal requirements. Some risks may not matter even one iota to a particular individual, whilst that very same risk can be stomach churning for another. Individuals can have Investment portfolio risks such as:

- Portfolio shortfall – The risk of not having sufficient cashflow to meet a specific financial obligation, or to meet an expected/desired future lifestyle

- The risk of a drawdown – how much is the maximum your portfolio can be expected to lose under normal circumstances, and how much is the portfolio likely to lose in an absolutely worst case scenario. This can be a $ amount, or a % performance. What is the likelihood of my portfolio being down x% in any 12 month period?

- The (inherent) risk of portfolio volatility – investing is built upon the premise that the future is uncertain, and as new data comes to light, investors react to that data by repricing securities. Oftentimes, the data is confusing, and is unclear as to the extent, magnitude or even direction that the price should change as a result. The price can easily whipsaw back and forth, resulting in extreme price movements in both directions. It becomes difficult to determine what is background noise and what price action is the beginning of a more meaningful drawdown. Volatility also tends to increase on the downside, as fear and emotion get the better of one’s rational judgment, and people end up making rash decisions.

- The risk that my investment portfolio will underperform its benchmark or a peer-group

- The risk of unforeseen circumstances- Life happens, and negative events with a large financial impact can affect anyone at any time. Whilst it is impossible to mitigate, there is the constant risk that an immediate and unforeseen liquidity need will arise. This risk is likely to have a more meaningful financial impact and hence needs to be taken into greater account when constructing a portfolio for individuals who have not yet managed to accumulate sufficiently high wealth.

4. So now that some of the main risks are known, I need to conduct a thorough introspective search into my own behavioral biases.

Behavior is arguably the most overlooked element of investing. The good news is, that (I imagine), I am speaking to a large homogenous group; specifically human beings (if you are not human, then well done for making it this far). The bad news, is that as human beings, we have been wired with inbuilt biases based upon personality and emotions. Worse, we tend to be unjustifiably confident that these biases don’t apply to ourselves, or else don’t even realize that we are somewhat blinded to our own biases.

Some common biases that we tend to possess that makes investing all the harder include:

- Overconfidence in our own abilities

- Confirmation bias- we are more likely to look for information that falls in line with our own pre-determined conclusion and beliefs

- Loss aversion- we tend to hate losses much more than we value gains and may focus on loss minimization as opposed to profit maximization

- We are slow to move away from our views even as new information comes to light that may/should alter that viewpoint

- Sunk costs – we tend to allow past events that have cost us in terms of time, money or effort to affect our future decision making

- Our own personal experiences are probably the number one determinant in how we shape personal views on the risk/reward nature of financial market investing

- We have a hard time predicting how we will behave in future stressful situations and have high expectations that we are in control and will react rationally in those situations.

Investors need to realize that although in the long-term markets tend to be driven by fundamentals, short term performance has more to do with luck than skill. In fact, Investing lies in a peculiar domain in that is somewhere between luck and skill.

Internalizing that you too are human, and hence are just as susceptible to emotional behavioral biases as everyone else is a significant first step. In fact, as crazy as this sounds, recognizing that you don’t have a behavioral edge over and above anyone else may well be the competitive edge that you possess over everyone else. Knowing yourself and your behavioral biases will help avoid making long term catastrophic decisions that are based upon short term emotions.

Some questions that may help one in discovering their emotional state that may drive emotional investing includes:

- How comfortable were you during prior market drawdowns?

- What would you say your tolerance level is – how bad did things have to get before you couldn’t sleep at night or felt sick to your stomach? 10%? 20%? 40%? More?

- When markets were in the midst of a 25% drawdown, was the glass more full, or more empty? Are you happier that you can now buy into the market at a discount, or are you more worried that you have lost money in your existing portfolio?

- How often do you feel the need to check on your investment portfolio?

- Which investment are you more likely to sell – one that is sitting on a gain or a loss?

- How quickly do you feel frustrated that an investment is not meeting your expectations?

Answering these questions honestly will allow you to develop a sense of whom you are as an investor, and how you are likely to behave during future periods of market stress. Asking these questions will not necessarily remove behavioral biases which tend to come as a second nature, however, they will allow you to determine as to the appropriateness of a given portfolio in helping you to reach your investment objective.

5. And that leads us back to the beginning. Once I know where I want to get to and have mapped out the different routes that may possibly get me to my destination; I have outlined the potential risks I am likely to encounter along the way; and we have thoroughly conducted a personal introspection into my own personal behavioral personality traits, then I can better ascertain the likelihood of being able to having the mental capacity to stick to the path and determining whether or not a given investment strategy is likely to get me to my intended target. Even a mediocre investment strategy that I am able to stick to is WAAAAAY better than a great strategy that I don’t have the ability to withstand in periods of stress. Investing is like a diet – there is no one diet that works and speaks equally to everyone.

As we know, there are no guarantees of anything in the stock market. Except maybe that it’s guaranteed to do your head in! However, we also know that with a sufficiently long time horizon, then chances of generating decent long term returns actually increases. Of course usual disclaimers about past performance not being a guarantee of future success applies – yadda, yadda, yadda.

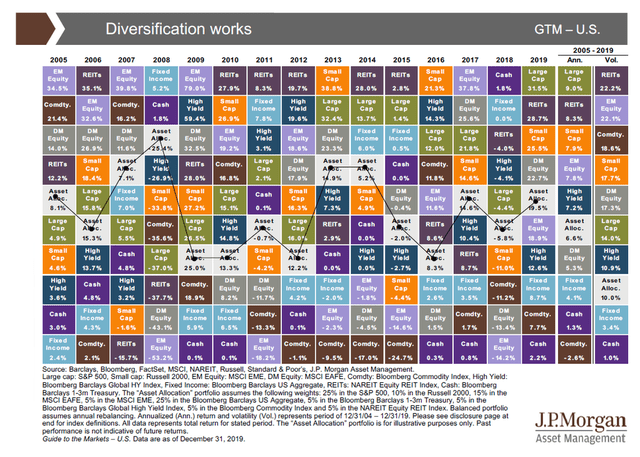

But the reward for short term volatility in the market is long term financial gain. Look at this chart showing the annual performance of various asset classes over the last 15 years. In any individual year, it’s downright scary and volatile. Down 40%, up 50%, etc., etc. But over the long term, despite these massive downturns over the shorter time frame, the long-term returns have been nothing short of impressive:

(As a side point, this highlights the necessity of portfolio diversification, as I illustrated in my article on the benefits of portfolio diversification). So with several of the risks being dependent upon volatility, drawdowns and performance, how can we determine the likelihood of a specific portfolio acting in a way which is outside my pre-determined comfort zone?

The simplest way would simply to do a historical back test. If I would have invested in this very portfolio 1, 3, 5 etc. years ago, how would I have performed? What would my maximum loss over the period have been? What was the volatility like? What return did I achieve? And then compare it to my initial portfolio objectives, and whether the portfolio would have fallen within my personal risk tolerance levels. Of course a back test gives no indication of whether this return would be achievable going forward, but it does provide a level of comfort in knowing exactly how a given portfolio would have behaved had I been invested in it up to now.

A more sophisticated approach would be to run Monte Carlo simulations for the specified portfolio based upon historical or forecasted returns to test long term expected portfolio growth and survival, and the capability to meet financial goals and liabilities.

Other risk management tools include staggering one’s entry points into the market over a period of several months or quarters, which mitigates the risk that markets take a leg down immediately following deployment. Of course, one runs the risk that markets actually trends upwards over the deployment period, and you would have been better off investing as a lump sum. (I hope to conduct an analysis of lump sum investing versus Dollar Cost Averaging (DCA) in a future post).

At the end of the day though, markets are going to dance along to their own volatile tune, and try to inflict the most amount of pain on the highest number of participants possible. 2022 so far has been pretty brutal, and has tested the nerves of even the greatest investors. Global equity markets are currently down anywhere between 20% and 30%, depending upon the region and sector. Yes, there have certainly been several counter rallies. But the prevailing trend has been down, down, down. Which is in direct contrast to the majority of the last 13 years or so, when the prevailing trend was up, up, up. Will they go down further? Will they bottom here? I wish I had a crystal ball. But I don’t expect that anyone will be ringing a bell at the bottom, just like they don’t raise a red flag at the top. What is of paramount importance though is that you come prepared with a financial plan. And every financial plan should come with an expectation that markets should undergo periods, often long ones of market stress.

Use this period of market stress to review your financial plan and make sure it is still applicable. Did your portfolio perform worse than you expected? Did it induce (too many) sleepless nights? Or were you able to stick to the drawing board, with the confidence that your plan took into consideration the bad times as well as the good?

Ultimately, bear markets are opportunities for long-term investors. Bear markets are never enjoyable. Heightened volatility is indeed scary. There are many excuses to not own stocks right now: inflation, rising interest rates, recession, war, stagflation and a whole host of others. There are far fewer reasons to want to hold stocks. Except for the fact that market valuation across several metrics are significantly lower today than at any time over the last few years (bar about 5 minutes during the initial COVID panic). And generally, lower valuations are opportunities for investors to buy, rather than sell, stocks. Volatility comes hand in hand with markets. Controlling volatility is not a solution that is within your control. How you react to that volatility is very much in your control.

Be the first to comment