Douglas Rissing

On Friday, October 7, the markets reacted to slightly better-than-expected labor market statistics with a huge selloff, and not for the first time, we should add. We see it differently.

For starters, these monthly job figures are a backward-looking variable, and job creation is almost surely going to come down. The unemployment rate will go up as the sharp turn in monetary and fiscal policies start to bite.

A host of indications already point to inflationary pressures easing, from house prices to commodity prices to shipping cost to stock markets to monetary aggregates, as far as the eye can see.

The CPI and even more the core CPI are backward-looking and react to a considerable lag to changes in the housing market (as we explained here).

But the focus on the labor market is misguided in another sense, inflation didn’t originate in the labor market, so the whole focus on Phillips curve-like tradeoffs misses the point.

This is actually quite surprising, as the labor market, which was already very tight before the pandemic, has been made extremely tight by the pandemic.

This happened through the expansionary monetary and especially fiscal policies, and one doesn’t have to invoke any “Great Resignation” to explain that the pandemic produced a big reduction in the labor supply

There are the people that died (1M+, although the majority wasn’t in the labor force), got long covid and are too sick to work (2M-4M), or got early retirement (3M+) or needed new caregivers.

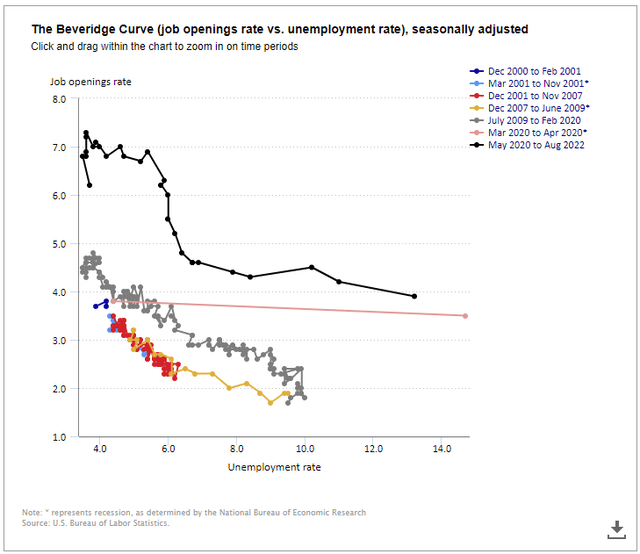

There were also large shifts in demand which the labor market can’t instantly accommodate under normal circumstances, let alone during a pandemic. This caused an outward shift in the Beveridge Curve:

It is extraordinary that with unemployment at or close to record lows and many more job openings in relation to the unemployment rate than usual, wages have been so relatively well-behaved.

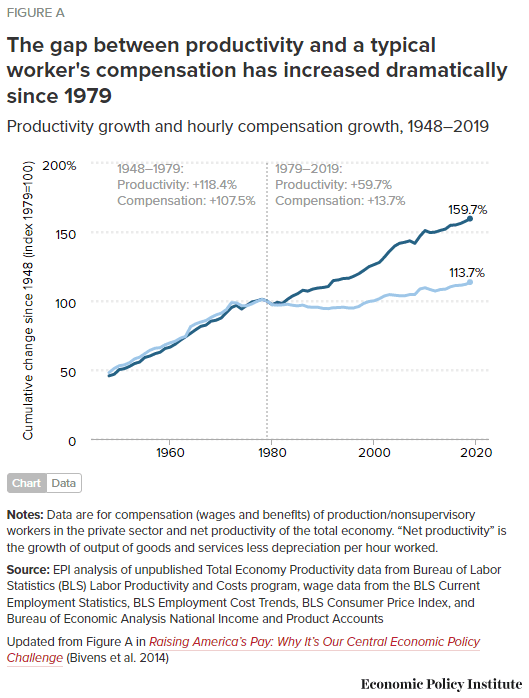

This testifies to the big shift in power away from employees to corporations. Median workers haven’t done so well and their pay has lagged productivity growth since the early 1980s (and further buffeted by huge price increases in education, healthcare and housing), from the EPI:

EPI

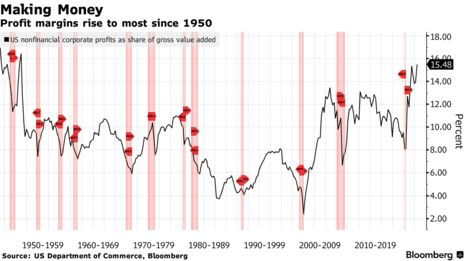

Most of this is actually explained by a rise in inequality (the top wages rising much faster), and some of it by an increase in the profit share of national income, from Bloomberg:

Bloomberg

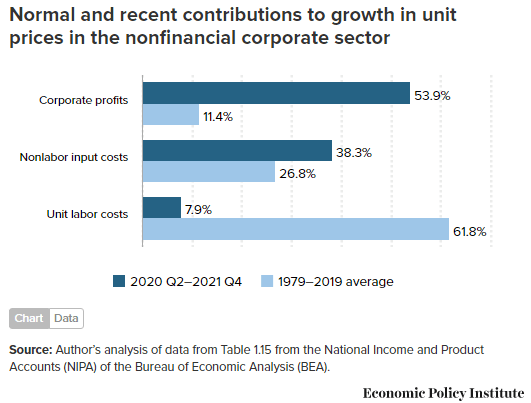

Contrary to previous episodes of inflationary pressures, wage costs have contributed little this time around, from the EPI:

EPI

Businesses, at least so far, have been able to pass on most cost increases and then some, from Bloomberg:

A measure of US profit margins has reached its widest since 1950, suggesting that the prices charged by businesses are outpacing their increased costs for production and labor.

Not only has their relative power versus most employees shifted in their favor, there is also a rise in market concentration that has contributed to this increase in pricing power.

With the economy weakening, this might not last, and while wages haven’t been a problem so far, that doesn’t mean they can become a problem, especially if inflationary expectations take hold.

However, so far there is little sign of that happening. Inflation expectations are actually coming down and a few years out are pretty modest. Wage and price setters seem to still have faith in the Fed getting inflation under control eventually.

What we do have is wages trying to catch up with inflation, even if they lag inflation itself, and this produces a situation where 6% wage growth is not compatible with 2% inflation (the long-term Fed policy goal), which is why the tightening of policy is justified even if the labor market will bear most of the (domestic) brunt and isn’t responsible for inflation in the first place.

A decades-long shift in power away from most employees’ bargain power has produced a situation in which wage growth is below inflation even in a very tight labor market. Inflation certainly didn’t originate in the labor market and it’s unlikely to become an important contributing factor.

With vacancies coming down and the labor market easing, this power is further eroded, so there is little danger of a wage-price spiral developing. Even if wages try to catch up for lost purchasing power, this, too, will ease, as inflation is already coming down almost everywhere but the CPI.

If we add the specter of a rapidly worsening world economy, financial stress, and an easing of supply constraints, we think the Fed will be done tightening sooner than the market seems to discount.

Be the first to comment