Khanchit Khirisutchalual

“We are in a perpetual state of learning, and that can make any prior fact obsolete.” ―Annie Duke

Thinking in Bets, written by world class poker player Annie Duke, stresses the importance of separating outcomes from the decision-making process. One must avoid “resulting,” or judging the quality of a decision based solely on an outcome rather than how the decision was made. While luck plays a role in just about every decision, all one can do is make the best decision with the given information to maximize the expected value of their decisions. As Duke stated:

“Decisions are bets on the future, and they aren’t “right” or “wrong” based on whether they turn out well on any particular iteration. An unwanted result doesn’t make our decision wrong if we thought about the alternatives and probabilities in advance and allocated our resources accordingly.”

Market participants often succumb to “resulting” and applaud themselves for great outcomes when they were just lucky. Alternatively, participants bemoan investments that fail despite being a good decision based on the probability of earning an attractive return at the time of investment. Noble Prize in Physics recipient Richard Feynman once said “The first principle is that you must not fool yourself…. and you are the easiest person to fool.” Investing, like poker, involves a constant series of decisions and ends with a good or bad outcome. Unfortunately, humans tend to confuse the quality of the decision based on the outcome—a good outcome is a result of a good decision, and a bad outcome is based on a bad decision. Investors can experience a good outcome despite a bad decision process, just as an investor can suffer a bad outcome even though the quality of the decision-making process was solid.

To avoid “resulting” when investing, one needs to focus on the process. The investment process should be agnostic and adaptive within a rational framework. The investor must acknowledge their biases and look for contrarian opinions. Value investing is a philosophy that emphasizes the need to perform fundamental analysis, pursue long-term investment results, limit risk and resist crowd psychology. By focusing on the process, positive outcomes emerge over a complete market cycle. Investing, just as in life, is a perpetual state of learning and learning compounds over time. Importantly, humans learn the most by having “skin in the game,” a term popularized by Nassim Taleb to mean having a measurable risk at stake when making important decisions. A fund manager that takes a percentage of profits on wins, but no penalty for losing, is incentivized to take undue risk.

Even after excluding Warren Buffett’s 16.2 percent ownership stake in the company, the directors on Berkshire Hathaway’s (BRK.A, BRK.B) board have a lot of skin in the game. Tom Murphy’s recent resignation from the board, at the age of 96, represented the departure of a major shareholder; $370 million according to the company’s 2021 proxy statement. Tom Murphy not only fulfilled the requirement of having a significant ownership interest in Berkshire Hathaway, but his career also serves as a case study on the capital allocation and investment decision-making process. According to William Thorndike’s book, The Outsiders, one dollar invested with Tom Murphy when he became CEO of Capital Cities Broadcasting in 1966 grew to $204 by 1996 when he sold the company to Disney (DIS) —a 19.9% annualized return over nearly three decades compared to 10.1% for the S&P 500.

One cannot attribute ‘resulting’ to Tom Murphy’s success—the quality of his decision process when allocating company capital was par excellence. His journey began in 1954, when Murphy accepted a job offer to run a small television station in Albany that recently emerged from bankruptcy. Despite having no formal management experience, Murphy took immediate control of the television station and improved its operations to the point where it was soon generating consistent cash flow. Murphy was soon entrusted with the management of two additional television stations, collectively called Capital Cities Broadcasting. When he assumed the role of CEO in 1966, having grown through additional acquisitions over the preceding decade, Capital Cities annual revenue was $28 million.1

Over the next four years, Murphy completed a series of acquisitions culminating in the $120 million purchase of Triangle Communications. By 1970, Capital Cities owned the maximum number of television stations permitted by the FCC and Murphy turned his attention to newspapers; still an attractive business in the 1970s. He purchased the Fort Worth Telegram for $75 million in 1974 and the Kansas City Star for $95 million in 1977. Murphy clearly wanted to grow the size of Capital Cities, but he never lost sight of the fact that growth through acquisition only creates value if it can be accomplished at sensible prices: “The goal is not to have the longest train, but to arrive at the station first using the least fuel.”

Because ego drives many corporate decisions, few executives are willing to shrink their companies. By repurchasing shares, a capital allocator surrenders cash that might otherwise be used to expand the empire in exchange for reducing the total number of shares outstanding. During the bear market of the 1970s, Murphy aggressively repurchased company stock because he was able to acquire shares at very low valuations. When Murphy became CEO of Capital Cities in 1966, CBS had a market capitalization that was sixteen times larger than Capital Cities. Thirty years later, Capital Cities was three times more valuable than CBS when Disney acquired the company. CBS focused on building the longest train through expensive acquisitions and wasteful expansions, while Tom Murphy focused on strategic acquisitions, cost controls, and shrewd share repurchases.

In 1986, Capital Cities acquired ABC for $3.5 billion, a massive acquisition financed by Warren Buffett through Berkshire Hathaway. Murphy once again set about improving margins through a combination of cost cutting and adopting the same business practices and efficiencies that had produced the much higher margins at Capital Cities. Out went the first-class airfares and limousines enjoyed by executives of the old ABC, replaced by coach seats and the yellow taxicab. In 1996, Disney acquired Cap Cities/ABC for $19 billion, a multiple of twenty-eight times net income. By comparison, Tom Murphy repurchased company shares in the 1970s at single digit multiples of earnings.

The ability to successfully allocate capital transcends talented individuals and is sometimes forced upon an entire industry. After years of pouring money into boosting energy production volumes, the U.S. energy shale patch emerged from the pandemic-induced crash with a newfound belief in capital discipline. When combined with oil prices above $100 per barrel, American oil producers are now generating record cash flows. After years of bleeding cash, energy companies have refocused on returning capital to shareholders. The days of “drill, baby, drill” are no longer the industry’s goal. High oil prices and strict capital expenditure discipline have resulted is an energy industry that expects to produce free cash flows of $172 billion in 2022, according to Deloitte. In comparison, America’ shale industry generated $300 billion in net negative cash flow over the last fifteen years. Unlike previous upcycles, American energy companies are now directing a large part of their record cash flows to increasing shareholder returns with higher dividends, special dividends, and share repurchases. Strong price gains reflect the changes in the energy industry and is attracting interest from investors who recognize the industry’s fundamental change, as well as speculators attracted to rising stock prices.

Because investors often succumb to “resulting” and applaud themselves for great outcomes when they were just lucky, many retail and institutional investors are in fact momentum investors. They chase returns and buy into the more recent outperforming asset classes or fund managers, while selling underperforming assets. Institutional investors tend to focus on three- to five-year horizons, reflecting their typical performance evaluation periods. Harvard University’s endowment fund said that they would divest all holdings in fossil fuels.2 Perhaps this move was due solely to concerns about global warming, but maybe it simply resulted from the horrible returns that the energy industry produced during the previous five years.

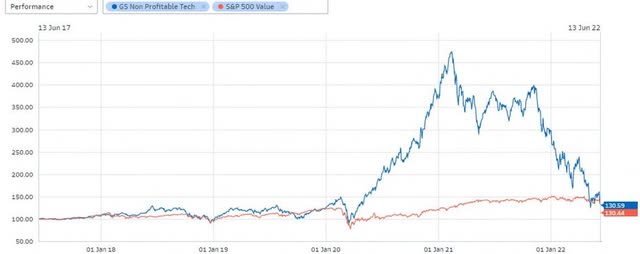

Just as institutions were abandoning the energy sector, technology-focused Tiger Global became one of the largest hedge funds in the world. Including leverage, the firm managed about $125 billion by 2021 according to a filing with the Securities and Exchange Commission, a far cry from the fund’s humble beginnings in 2001 when Julian Robertson first seeded Chase Coleman with $25 million.3 In 2020, Tiger Global’s hedge fund topped a widely followed industry performance list, when its aggressive technology stock holdings skyrocketed. Tiger Global’s assets tripled over the period from 2020 to 2021, collecting billions of dollars from institutional investors like endowments, pension funds, sovereign- wealth funds, and billionaires desperate to get a “piece of the action.”

During the early days of the covid pandemic, money flooded the financial markets; cryptocurrency and consumer-oriented technology stocks soared during the work-from-home craze. Tiger Global’s venture capital funds financed many of these early-stage companies and subsequently owned them in their hedge fund following their respective IPOs. Today, many of the stocks that Tiger Global owns have been obliterated in the new environment of higher interest rates and rising inflation; the fund has suffered losses every month in 2022 and is down over 52% on the year as of the end of May. The fund recently announced limits on investor withdrawals and fee reductions to entice new capital. With hindsight, one sees how Tiger Global, and its clients got into its current predicament. “They’ve just been winning, and winning, and winning,” one industry analyst noted. “I think one thing that happens to people who win, win, win, win, is they get overconfident, and they can’t imagine a scenario where they’re not winning.”4 Surprisingly, even after these historic losses, Tiger Global has seen five times more inflows than redemptions requests, according to Bloomberg.

Just as institutions cannot kick their Tiger Global addiction, retail investors remain committed to Cathie Wood’s flagship Ark Innovation ETF (ARKK), today’s posterchild for speculative excess. The fund recently posted its longest streak of inflows in over a year as it battles the same forces that are currently dismantling Tiger Global’s portfolio. Despite the fund’s 72% decline from its peak in February 2021, Cathie Wood continues to exercise the courage of her convictions by doubling down on her innovation- themed strategy while retail investors continue to pour money into the “disruptive innovation” fund. As if retail investors did not already have enough excitement with the Ark Innovation Fund, the ProShares UltraPro QQQ exchange traded fund (TQQQ), which seeks to generate three times the daily performance of the Nasdaq 100 Index, has taken in a net $7.7 billion in investor cash year-to-date in 2022. Unfortunately, retail’s stubborn persistence has not been rewarded: the fund is down 57% year to date.

The downdraft in technology stock prices has hardly shaken the market’s faith in a brave new world, as evidenced by Tesla’s (TSLA) still massive $708 billion market capitalization, equivalent to more than eight times the company’s expected full-year revenue. Ford (F) and General Motors (GM) , by comparison, carry market valuations of $46 billion and $48 billion, respectively, against projected 2022 sales of roughly $150 billion each. The stock market values competitor Volkswagen A.G. (OTCPK:VWAGY) at $85 billion while the company expects to generate $288 billion in sales this year. A decade-long run of low interest rates which encouraged investors to speculate on high-growth technology start-ups might finally be ending. With the war in Ukraine creating unpredictable macroeconomic waves and inflation unlikely to abate anytime soon, even the stock prices of the largest technology companies are faltering, with shares of Amazon (AMZN) and Netflix (NFLX) falling below their pre-pandemic levels. Growth at any price might not just be enough anymore.

Although innovation is extremely beneficial to society, it does not always reward investors. Investors have long struggled to understand how an incredible and disruptive innovative technology can also prove to be a bad investment. When studying previous periods of innovation, one learns that they are not mutually exclusive. Society benefits at the expense of investors. At the height of the dotcom bubble, Warren Buffett noted during a speech:

I thought it would be instructive to go back and look at a couple of industries that transformed this country much earlier in this century: automobiles and aviation. Take automobiles first: I have here one page, out of seventy in total, of car and truck manufacturers that have operated in this country. At one time, there was a Berkshire car and an Omaha car. Naturally I noticed those. But there was also a telephone book of others. All told, there appear to have been at least 2,000 car makes, in an industry that had an incredible impact on people’s lives. If you had foreseen in the early days of cars how this industry would develop, you would have said, “Here is the road to riches.” So, what did we progress to by the 1990s? After corporate carnage that never let up, we came down to three U.S. car companies — themselves no lollapaloozas for investors. So here is an industry that had an enormous impact on America — and an enormous impact, though not the anticipated one, on investors.5

Today, few market participants seem overly troubled by a potential crisis or deep recession. The most common question among investors these days remains when to “buy the dip.” From random conversations, one senses that market positioning remains bullish. While investors have increased their cash allocation, most maintain a positive view of the economy. The average consensus expects a modest reduction in consumer demand and a U.S. Federal Reserve that will soon return to its accommodative ways. Market speculators are actively wagering that central banks will soon change their policy back to lower interest rates despite a decades-worth of accumulated risks in the economy. Many years of a “buy the dip” mentality driven by fiscal and monetary accommodation have enticed many to take significantly more risk than what they likely perceive. Two generations of market participants have seen nothing but expansionary monetary policies, creating a level of entitlement that expects central banks to rescue poor investment decisions. Rather than focus on central bank policy, investors would be better served stress testing their portfolios should markets begin pricing unexpected scenarios.

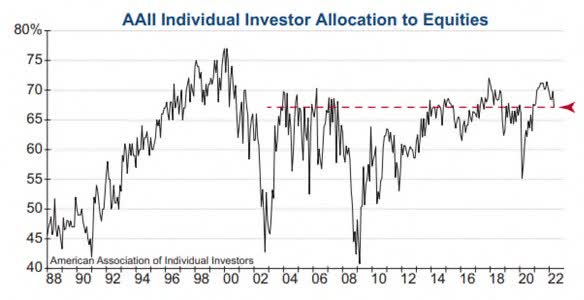

The troubling aspect of this bravado in the face of tangible concerns is that very few investors have adjusted their stock portfolios. According to the AAII survey of individual investors, the average allocation to equities is still at one of the higher levels of the past twenty years. This “stay the course” mentality is a result of thirteen years of a relentless bull market, interrupted only briefly by a pandemic panic in early 2020. Since the bear market low in March 2009, investors have repeatedly been conditioned to “buy the dip.” Years of retail investors buying indexed funds and ETFs to benefit from an ever-rising market, coupled with heavy institutional directional bets predicated on the “fear of missing out,” can quickly unwind when faced with unexpected outcomes.

Financial markets reflect human emotions; rationally, they are never as bad as one fears, but seldom as good as one hopes. The reality normally lies somewhere in the middle. If one realistically assesses the current market situation, stocks are returning to prices in line with long-term average valuations and bond yields are revisiting more appropriate levels that discount the most efficient allocation of capital across a market-based economy. Inflation finally popped the illusion created by a generation of low interest rates and easy access to liquidity. Unfortunately, the adjustment will be painful for some, particularly those who predicated their investments on “resulting” and applauded themselves for great outcomes when they may have been just lucky. Alternatively, investors who remained disciplined and invested within a framework of earning an attractive return of their invested capital should excel in an environment that reverts to a rational mean.

With everyone fixated on the stock markets for clues to what happens next, recall Warren Buffet’s simple stock market valuation model: the ratio of total U.S. stock market value to the total production of the U.S. economy (GDP). His observation concluded that the U.S. stock market is overvalued above 90% of GDP. Today, the value of U.S. stocks is roughly $41 trillion while the GDP is $24 trillion, a ratio of 170%.

The 90% fair value level is subjective and interest rates remain historically low; therefore, maybe fair value resides around 110% – in which case stocks remain around 35% overvalued. Fortunately for the discerning value investor, that market scenario will not impact every stock equally. Many well-managed companies are beginning to trade at attractive valuations for long-term investors—a list that excludes Tesla and other ‘disruptive innovation’ companies that benefited from ‘resulting.’

Legendary investor Sam Zell, who earned the name “Grave Dancer” by buying up office properties for pennies on the dollar during the real estate bust of the 1980s, understood risk better than most but began life with the benefit of luck. Sam Zell’s parents escaped from Poland at the onset of the Nazi invasion. To get to the United States, they needed to get out of Europe. Fleeing to Vilnius, Lithuania, they were able to acquire forged entrance visas for Curacao, but first traveled through Russia and Japan, a journey of 8,000 miles.6 Sam Zell was born four months after his parents arrived in America. Zell’s parents left Europe, knowing they would have died, and came to America with very little and not able to speak the language. Still, they forged a successful life over the next forty years. Zell’s father always maintained the belief that the streets in America were paved with gold and filled with opportunity.

As the child of immigrants, Zell saw the United States as a combination of golden streets and shadows over his shoulder, which subsequently shaped his perspective of risk and reward.

“I’ve always operated on the thesis that if whatever I do is profitable, I’m pretty well protected. The real question is when you initially make the decision — when you initially take the risk — do you understand what the downside is? Do you have enough staying power to, in fact, be able to succeed in an environment that meets your downside definition?”

– Sam Zell

Although he had no formal investment training, Zell is a classic value investor. He evolved over the decades to earn outstanding returns across various asset classes – from real estate to operating companies. Zell’s flexibility is a testament to his ability to continuously adapt and learn with his “skin in the game” while always seeking value with his investments. As financial markets revert to their long- term average valuations, investors like Zell stand to generate incredibly attractive returns on their investment capital.

With kind regards,

St. James Investment Company

Footnotes

1‘Business Lessons from Tom Murphy,’ The Rational Walk, 8 April 2022, Business Lessons from Tom Murphy murphy/.

2‘Harvard University will divest its $42bn endowment from all fossil fuels,’ The Guardian, 10 September 2021.

3https://reports.adviserinfo.sec.gov/reports/ADV/160318/PDF/160318.pdf

4Michelle Celarier, ‘Masters of the Bubbleverse,’ Intelligencer, 17 June 2022.

5Carol Loomis, ‘Mr. Buffett on the Stock Market,’ FORTUNE, 22 November 1999.

6Edward Mendlowitz, Withum Advisory, “Sam Zell’s parents’ story,” 8 August 2017.

Editor’s Note: The summary bullets for this article were chosen by Seeking Alpha editors.

Be the first to comment