spooh/E+ via Getty Images

After receiving competing offers from Frontier (ULCC) on February 7th and JetBlue (JBLU) on April 5th, Spirit Airlines’ (NYSE:SAVE) Board expressed their preference for a lower but presumably less risky ULCC proposal. Since then, JBLU launched a hostile tender offer and both bidders have eventually improved their proposals to include or increase reverse termination fees. Currently, JBLU offer is superior at $30 per share in cash (with the potential to reach $33 per share) and a prepayment of $1.50 per share of the reverse break-up fee (total break-up fee of $350 million). ULCC has stuck to its offer of 1.9126 of ULCC shares and $2.13 in cash for each SAVE share (currently worth $19.50) but introduced a reverse break-up fee of $250 million. SAVE’s Board still favours ULCC’s offer but it seems that SAVE shareholders are pushing the company’s Board to consider JBLU’s latest proposal. Postponed shareholder meeting is one indication that the Board may be shifting towards accepting the JBLU offer.

Timeline

Here is a timeline of events in this all-action merger arbitrage set-up:

-

February 7th – SAVE receives an acquisition offer from ULCC. For each SAVE share, stockholders would receive 1.9126 of ULCC shares and $2.13 in cash. At the time, the offer was worth $26.65, presenting a 5% spread.

-

April 5th – JBLU launches a superior proposal to acquire SAVE at $33/share. SAVE share price spikes to $26.92.

-

May 2nd – SAVE announces that it favours the ULCC offer, adding that there is significant regulatory risk.

-

May 16th – JBLU commences a hostile tender offer for $30/share in cash.

-

May 19th – SAVE urges shareholders to reject JBLU tender offer, arguing that it was made just to disrupt the original SAVE-ULCC merger and contains “substantial regulatory hurdles”.

-

May 31st – Proxy advisory firm ISS recommends SAVE shareholders to reject the ULCC deal. SAVE management disagrees, stating that the company would face significant “business disruption” if the transaction with JBLU fails after 18-24 months, even though the deal has a reverse termination fee, unlike the ULCC bid.

-

June 2nd – SAVE and ULCC amend their agreement to include a reverse termination fee of $250 million or $2.23/share.

-

June 3rd – Proxy advisory firm Glass, Lewis & Co. recommends Spirit shareholders to vote for the SAVE-ULCC merger.

-

June 6th – JBLU improves its offer to $30/share in cash plus a prepayment of reverse break-up fee of $1.50 per share in cash (reimbursable if the deal closes).

-

June 8th – SAVE postpones its shareholders meeting scheduled for June 10th to June 30th.

Investment Thesis

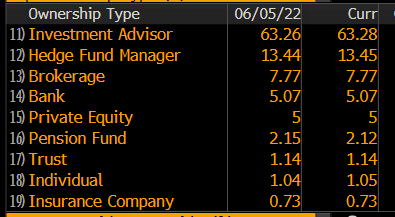

JBLU’s offer is clearly superior to ULCC. Not only is it higher, but it also has value certainty – all-cash transaction versus cash plus stock of ULCC which implies market risk. An important point is that SAVE’s shareholder base is investment advisors, hedge funds and brokerages. Moreover, average trading volumes are high. This means that the equityholders here likely have a strong incentive to explore JBLU’s higher offer and hence appear to be pushing the company’s Board. Proxy advisory firm ISS advising against the SAVE-ULCC deal only reinforces this shareholder base incentive.

Bloomberg Terminal

On the other hand, the buyer, JBLU, appears to be committed to the transaction (also discussed in Regulatory Risks). It has signalled its intention to up the offer price further (“if SAVE’s Board allows minimal diligence, JBLU is willing to negotiate a consensual deal on the basis of $33/share”) while pushing aggressively for SAVE shareholders to exercise appraisal rights and reject the ULCC transaction.

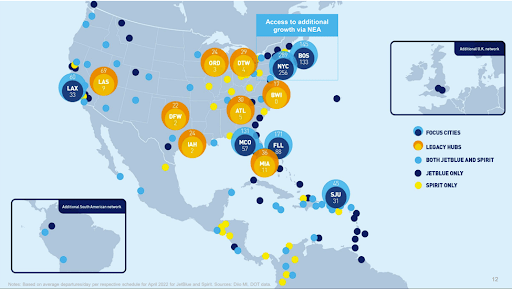

This acquisition has a clear strategic rationale for JBLU. Fundamentally, the US airline industry is dominated by the “big four” airlines. JBLU has argued that the JBLU-SAVE combination would more impactfully lower “big four” fares than SAVE-ULCC. Reportedly, this has historically been the case due to the so-called “JetBlue Effect”, partly because of the company’s credible coach service (free and fast internet, unlimited snacks and drinks and most legroom among competitors). The company states that “JBLU’s presence on a nonstop route decreases legacy fares by ~16%” – 3x more than ultra-low-cost-carriers”. Expected annual run-rate synergies are $650 million (versus $500 million for ULCC-SAVE), fleets are complementary as well (primarily Airbus A320s) and JBLU would expand its operations in Chicago, Las Vegas, Dallas, Houston and the Caribbean and Latin America (the same is mostly the case for ULCC).

All of this suggests that the two sides will eventually reach an agreement which will boost SAVE stock price. Currently, SAVE trades at a 41% spread to JBLU’s proposal price ($30 per share in cash), indicating a large upside.

Regulatory Risks

Antitrust concerns are the main risk, but it appears that JBLU can manage to overcome them. So far the regulators have not made any comments on the proposed JBLU-SAVE merger. However, ever since Joe Biden’s executive order signed in July 2021 the markets have expected tighter scrutiny on many sectors, airlines among them. One ongoing JBLU issue is a lawsuit filed by DOJ to block a partnership (Northeast Alliance or NEA) in September 2021 between American Airlines and JBLU, even though both companies remained independent entities. The partnership agreement involved coordinating schedules but not airfares, also allowing companies to sell each other’s flights and combine loyalty benefits. In the context of JBLU wanting to acquire SAVE, a DOJ official stated that it wasn’t a good time to put yet another questionable piece on their docket (rephrased). JBLU CEO Hayes once mentioned that JBLU would not sacrifice partnership with AA in favour of the SAVE acquisition if regulators required it, however, JPMorgan has recently said that JBLU may “trade away the NEA partnership for a SAVE merger”. More recently, JBLU argued that the NEA litigation outcome would not have an impact on the merger, but nevertheless “a vigorous antitrust review” that “could last into 2023” would be expected for the SAVE-JBLU business combination.

Some analysts view JBLU’s proposal as fundamentally risky because of greater route overlap on the East Coast (mainly New York, Boston and Florida). For instance, both SAVE and JBLU are by far the two dominant carriers in Fort Lauderdale, a key South Florida airport. However, Kyle Stewart provides examples of many other airports where merged companies have had higher airport capacity shares and mergers were approved (for example, AA 84% market share in Dallas/Fort Worth Airport).

JetBlue Investor Presentation, April 4, 2022

JBLU addressed the last point in the offer made on June 6th by explicitly agreeing on a “remedy package” to divest all of SAVE’s assets in New York and Boston as well as gates and other assets in Fort Lauderdale. This would effectively resolve the main sticking points in antitrust considerations. Moreover, JBLU has raised its reverse break-up fee from $200 million to $350 million in its latest offer (~10% of JBLU’s market cap). This shows the willingness of JBLU to pursue the acquisition instead of just disrupting the ULCC-SAVE agreement as well as confidence that the deal would be approved. Regulatory risks certainly remain, but if SAVE management accepts JBLU offer, the current spread should narrow.

ULCC

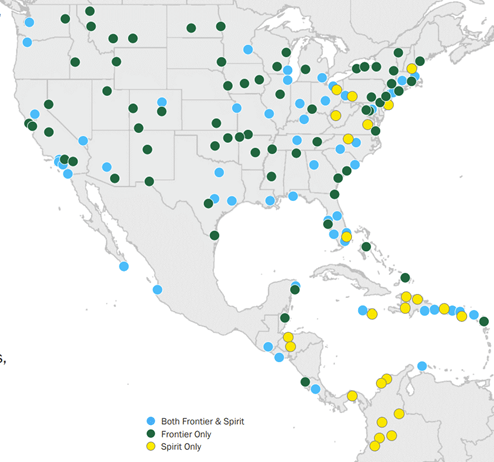

ULCC’s initial merger proposal has faced regulatory backlash as well. In March, US senators sent a letter to the DOJ Antitrust Division and DOT, expressing “concerns” and highlighting the merger’s alleged impact on prices. Lawmakers also highlighted that SAVE and ULCC have had the lowest customer satisfaction rates since 2017, meaning that the merger would “insulate them from the concerns of their customers, leaving mistreated ULCC travellers with no alternatives”. Moreover, SAVE-ULCC airport overlap has been significant and reached 80% in 2021 while individual route overlap was 40%, implying that there is a legitimate antitrust threat for ULCC-SAVE as well.

Frontier Airlines Investor Presentation, February 7, 2022

In any case, potential JBLU-SAVE regulatory review is likely to take a significant amount of time (probably until 2023). Meanwhile, in the short-term the ULCC offer would protect the downside if SAVE Board does not accept the JBLU bid. As for the downside risk, airline companies were a part of a broader market sell-off this year. Therefore, a 10%-15% decline to below pre-ULCC proposal levels (so ~$18-$19 per share) is reasonable if both deals fall through. Here I also take into account quite a low ULCC offer in the context of historical SAVE and ULCC prices.

Recent Mergers

There have been similar antitrust concerns from the DOJ. In 2016, DOJ provided clearance to Virgin America-Alaska Air deal with only limited code sharing amendments and without any divestitures, allowing interline and loyalty agreements. Interestingly, after the merger Alaska Air became the fifth largest airline, as would be the case for either JBLU-SAVE or ULCC-SAVE. Reportedly, JBLU also participated in Virgin America acquisition talks but failed in its bid.

Another case requiring regulatory intervention occurred in 2011 as Southwest acquired AirTran. This was the first major acquisition in the low-cost-carrier industry. In a similar way as SAVE, AirTran was based in Florida and served the Caribbean market extensively. DOJ concluded that: “The presence of low cost carriers like Southwest and AirTran has been shown to lower fares on routes previously served only by incumbent legacy carriers”. The reasoning certainly sounds familiar to the one expressed by JBLU in its SAVE bid.

Perhaps the most notorious merger occurred in 2013 between US Airways and American Airlines, as a concession had to be made to give low-cost competitors more slots in some US airports, however, only 112 of 6700 daily flights were affected by the concession. At the time, both companies controlled 69% of Reagan National Airport which was agreed to be lowered to 57%. Nevertheless, the merger allowed to maintain a high degree of concentration in some airports. Moreover, in a manner similar to the JetBlue-American Airlines partnership lawsuit, the lawsuit for the mentioned merger was filled by six US states. In the end, these states gained five-year guarantees of daily services, so the same thing may happen with the JBLU-AA partnership agreement instead of a complete termination of the partnership agreement. In the US Airways-AA case, the DOJ lawsuit was settled in four months, showing a relatively quick escalation.

Summary

SAVE Board is likely to reconsider its choices and proceed with the JBLU merger. JBLU’s commitment to get the deal done is solid as well as shown by both divestiture comments and significant reverse break-up fees. The downside appears to be protected by ULCC’s offer in the short-term. Although regulatory risk clearly remains, based on strategic rationale (i.e. lower fares via competition to “big four”) and previous airline merger experience, divestiture agreements rather than complete halt of the transaction could take place in case there is strict regulatory opposition. This suggests that the chances of the JBLU-SAVE merger closing, although far from certain, may be higher than implied by the market.

Be the first to comment