Ca-ssis/iStock via Getty Images

Spare a thought for the Fed. The hope that inflation had peaked in March was brutally dashed last week as headline inflation printed a new high of 8.6%. A 50bp rate hike this month is now all but certain, with many forecasters looking for 75bp. We could also spare a thought for the BoE. The Old Lady told markets last time it convened that it expects inflation to rise above 10% by Q4, that the economy could well fall into recession but that it will continue hiking anyway. Or maybe we should spare a thought for the ECB. Last week, Ms. Lagarde informed investors that the central bank intends to raise rates by 50bp, at least, between now and September, followed by “sustained and gradual” rate hikes. Yields and spreads rose on the day, likely more than the ECB would have expected, let alone liked, and the euro weakened. The central bank we shouldn’t spare a thought for, however, is the BOJ, apparently.

Before the supply-constrained economy that emerged after Covid, and the war in Ukraine, any attempts of a sustained rise in global short-term interest rates had to contend with the fact that at least two major central banks, the ECB and the BOJ, were stuck in the mud at the zero bound.

This, in turn, had obvious consequences for capital flows and currency movements as rates in other major economies, primarily the US, rose. More specifically, when two of the largest central banks in the world, presiding over two of the biggest piles of excess savings, are at the zero bound, it potentially limits the ability of both short-and long-term rates to increase elsewhere. This is especially the case in a world of free capital movement.

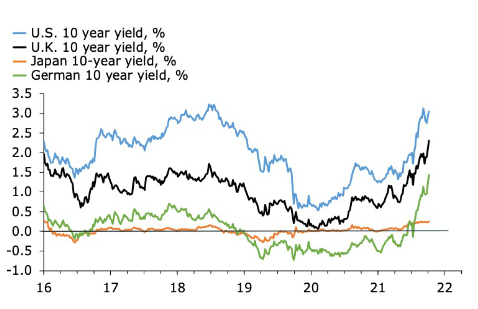

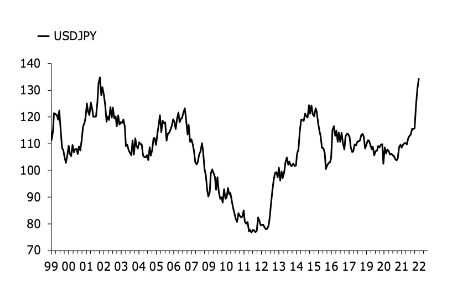

Fig. 01: Spot The Outlier… (Author) Fig. 02: … Its Currency Is Suffering (Author)

Now, however, the shoe has shifted to the other foot, thanks to higher inflation, which is proving neither moderate nor transitory. This brings us to the BOJ.

The first chart above shows that long-term bond yields have soared in the US, the eurozone and in the UK, but they have barely budged in Japan. This is because the BOJ had stalwartly stuck to its yield curve control, despite inflation zooming past its 2% target in April.

To be fair, given the decade-long experience of low inflation, if not deflation, in Japan, the BOJ could be excused for not jumping the gun now. If any central bank should be awarded time to see whether this bout of inflation might just end up being transitory, it is the BOJ.

Yet, markets are in no mood to offer Mr. Kuroda time, let alone room for manoeuvre. Investors seem intent on continuing to sell the JPY until and unless the BOJ lets yields rise, but if they do that, markets almost surely will switch to selling JGBs, rekindling uncomfortable attention on the reality of Japan’s public debt-to-GDP ratio at +250%. Maybe the by-now famously capsized Kyle Bass trade in 2013 is about to make a comeback?

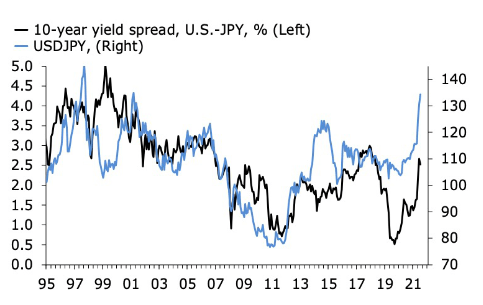

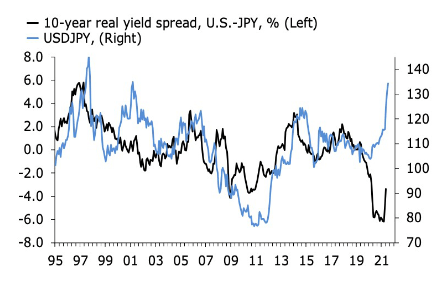

Fig. 03: Further Downside For JPY? (Author) Fig. 04: Real Yields Say No (Author)

Stuck between a rapidly weakening currency and a reset in the bond market, it makes sense for the BOJ to choose the former. For markets, however, a tasty setup is now emerging. Either it remains open season on the JPY, or the selling pressure is transferred to JGBs as the BOJ loosens yield curve control. Timing is everything, and there are no free lunches. Still, an options trade that exploits the potential for downside in JGBs, paid for by selling upside in JPY, or vice versa, now seems a good bet – if such a strategy exists, that is.

Meanwhile in Tokyo, Mr. Kuroda was criticized earlier this month for the comment that consumers are now more willing to accept higher prices. The problem, in this context, is that a weaker currency is now driving up prices in imported goods and inflation, while any boost to trade competitiveness is absent, due to the J-curve effect. The boost to export competitiveness will come, however, as will the lift to (unhedged) net foreign asset income, which drives a substantial share of Japan’s external surplus.

Last week, I spoke to my colleague Craig Botham, who oversees Pantheon Macroeconomics’ China and Japan coverage, about this. He agreed that the weaker JPY, and by extension the yield curve control policy, is now a headache for the BOJ to the extent that it drives up imported price inflation, a problem for both households and corporates. But what will the central bank do? Judging by recent news reports, not a whole lot.

One thing it will do, however, is to hope for lower inflation prints, both at home and abroad. Maybe then, it’s time that we spare a thought for the BOJ.

Editor’s Note: The summary bullets for this article were chosen by Seeking Alpha editors.

Be the first to comment