aluxum

The U.S. Federal Reserve (Fed) has begun raising rates, spurring concerns about the impact on fixed-income returns. Should emerging markets (EM) debt investors be concerned, or could this be a buying opportunity?

In this series—based on our paper—we examine the three previous tightening cycles that occurred during the life of this asset class to gauge the potential impact of the rate hikes on EM sovereign debt returns over the next 12 months and beyond.

In each post, we consider a key fear driving concerns about the future returns of EM sovereign debt. We then assess the legitimacy of each fear when compared to the three most recent Fed rate-hiking cycles: 1999 to 2000, 2004 to 2006, and 2015 to 2018. Because each of these past rate-hiking cycles differs in length, speed, and, more importantly, the context in which the tightening took place, we investigate the key differences as well as similarities that are likely to be important drivers of performance.

Let’s get started. The first fear driving concerns about the future returns of EM sovereign debt is that the sensitivity of EM debt to rising interest rates could hurt performance—particularly because EM debt duration is longer now than it was in previous Fed tightening cycles.

There are three main components of EM debt returns: the starting yield of the asset class; the change in EM debt spreads; and the sensitivity of yields to changes in U.S. Treasury yields.

Regarding the third component, the argument that rising interest rates—and as a result, rising Treasury yields—will hurt EM debt returns is particularly pertinent now, because the duration of EM hard currency debt has increased over the past 20 years as sovereign issuers have successfully extended the maturity of their U.S. dollar (USD) issuance.

When the 1999 rate-hiking cycle began, the duration of the asset class was as short as 4.57 years. It grew to 5.77 years in 2004 and 6.65 years in 2015. When the Fed raised rates from 0.25% to 0.50% in March 2022, the J.P. Morgan Emerging Markets Bond Index Global Diversified (EMBIGD) had a duration as high as 7.37 years. This increased the sensitivity of the asset class to the move in U.S. Treasury yields.

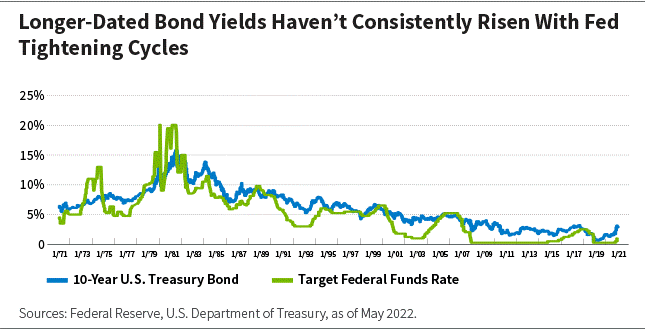

Having established that EM debt’s sensitivity to rising Treasury yields is higher now than in past Fed tightening cycles, we must ask if this should be a concern for investors—and the answer is that there is little historical evidence to suggest that Treasury yields will increase significantly once the Fed rate-hiking cycle has begun.

Using the change in the 10-year Treasury bond yield as a proxy for this risk, we can see that it is not clear that the onset of a Fed tightening cycle means that longer-dated bond yields will rise sharply. In some instances, the 10-year Treasury bond yield was actually lower a year after the initial rate hike. And after a multi-decade bull market for Treasurys, the 10-year Treasury bond yield had been range-bound since the global financial crisis (GFC). We expect this theme to continue as the market balances concerns about both inflation and growth.

What does the data show us?

1999 to 2000: Yields Rise

First, 10-year U.S. Treasury bond yields rose in the year following the 1999-2000 rate-hiking cycle.

After nine consecutive years of economic growth, strong domestic demand, and generationally low unemployment, the 1999-2000 hikes were largely preemptive.

The rate-hiking cycle lasted only six months and was limited to 125 bps of total hikes (albeit from a relatively high starting point of 5.25%).

Inflation was largely contained once the rate-hiking cycle started, peaking at 3.80% in 2000 before falling sharply as expected in 2001. At that point, the rate hikes were rapidly reversed.

In this era, positive real rates were the norm rather than the exception, and the 10-year Treasury bond yield actually rose from 5.62% to 6.28% a year later. This 66-bp rise was a headwind to EM debt returns.

2004-2006: Yields Fall

In contrast, yields fell in the 12 months following the 2004-2006 rate-hiking cycle.

In this rate-hiking cycle, the Fed sought to fight rising inflation and cool off an economy that was overheating.

This cycle was much more prolonged than the 1999-2000 rate-hiking cycle, with rates starting at 1.00% and finishing exactly two years later at 5.25%.

Unlike in 1999, there was a perception that the Fed was behind the curve when it started tightening. While growth decelerated gradually, inflation remained stubbornly above 3.00% throughout the tightening cycle (although it did not spiral out of control, and actually returned to more acceptable levels soon after the last rate hike).

In this case, the yield curve was already very steep when the Fed started raising rates, with the 10-year U.S. Treasury bond yield at 4.65%. It was 3.98% a year later. This 67-bp decline was a tailwind for EM debt returns.

2015-2018: Little Changed

Then, with the 2015-2018 rate-hiking cycle, we saw something different: U.S. Treasury bond yields were little changed.

Seven years had passed since the GFC necessitated a prolonged period of accommodative monetary policy. The decision to hike rates was supported by a more positive economic outlook (although there were some dissenting voices on the Fed, and as a result the so-called “gradualism back to normalcy” was dependent on economic data). Following a period of expansion, the Fed also communicated that it would not reduce its balance sheet for a significant time.

The rate-hiking cycle of 2015-2018 was longer than the previous two but less aggressive, with rates starting as low as 0.25% in December 2015 and ending at 2.5% three years later.

Under these circumstances, the yield curve, which began at a steep 200 bps, flattened during the rate-hiking cycle. One year after the first hike, the 10-year U.S. Treasury bond yield was at 2.45%, 17 bps higher than it was at the time of the first hike.

Our Verdict: No Yield Rise

Based on the three previous rate-hiking cycles, we believe there is little evidence that the 10-year U.S. Treasury bond yield will rise significantly in the year following the first Fed hike of the current cycle.

Similar to both the 2004-2006 and the 2015-2018 rate-hiking cycles, the curve was steep into the first hike this time around. At the time of this writing, the 10-year U.S. Treasury bond yield had already adjusted upward as the market priced in a higher Fed terminal rate. This is already a significant move and corresponds almost entirely with the rise of the 10-year U.S. Treasury bond yield in the 1999-2000 rate-hiking cycle.

We acknowledge that inflation is much higher this time around, but believe that it is largely driven by supply-side disruptions rather than an overheating economy and strong domestic demand. Therefore, we believe we may be close to peak inflation fear. A combination of both positive base effects and potential resolutions to supply-side disruptions could alleviate some current fears about where inflation and the federal funds rate might be headed.

We expect the 10-year U.S. Treasury yield to range from around 2.8% to 3.0% in one year’s time, with risks to the downside as a more aggressive front-loaded tightening cycle shifts the narrative away from inflation to concerns about slowing growth.

Editor’s Note: The summary bullets for this article were chosen by Seeking Alpha editors.

Be the first to comment