naphtalina/iStock via Getty Images

Media coverage of the Russian-Ukrainian conflict focuses on events and stories, given its focus on reporting the facts, the media doesn’t really analyze what will happen next. Hence the market appears to be surprised by events that aren’t really surprising, e.g. Russia’s weaponization of natural gas or the recent mobilization. As the conflict is not going well for Russia, it’s reasonable to expect they would up the ante – just because people make bad decisions doesn’t mean they roll over and give up. The upping of this ante has profound impacts on the stock market and is a major factor driving many important factors (e.g. inflation, supply chain worries etc.) So it is worth considering, what’s possible to happen next and how does the investor deal with this?

The situation Russia (or rather, Putin) is in right now is akin to a player in a poker tourney with a small stack of chips remaining while the blinds keep increasing:

- If he continues to wait, his stack keeps getting depleted by the blinds and he probably won’t last too many more hands,

- It is unlikely he’ll get a good hand within the next few hands to materially reverse his fortune

In such a situation, what would you do?

- Option A: Sit tight for a statistically unlikely successive good hands to reverse one’s fortunes

- Option B: Play aggressively in the hope it works out

Faced with such a position, it would only be logical for the player to try to play aggressive – even if the odds aren’t good, it beats doing nothing and getting bled to death. Maybe you get to steal some blinds or even get to flop a full house and get to stay in the game. Oh by the way, there’s no honorably exit to call it quits from this poker match for this player, for him it is essentially a deathmatch.

If we shift from the poker analogy to the situation in Europe right now, what do we see and what might happen?

Current situation:

#1: Natural gas embargo is not working: The natural gas embargo has wreaked havoc across Europe but the Europeans have held fast and are now working on substituting other sources of energy. Europe can probably survive the energy crisis – compared with the years during and after WWII which were far worse, a year or two of adjusting energy sources is going to be painful and inconvenient but unlikely to be lethal. In several years, US and Qatar LNG exports to Europe will be able to supplant for most Russian gas, and Europe is exploring nuclear, oil, coal and just about anything that can breathe steam.

#2 Combat situation is not looking favorable: Russia ups the ante by mobilizing but Ukraine is receiving just about unlimited supplies from the US (including the “Lend-Lease” act that went into effect on October 1 and allows the US to provide more supplies faster).

#3 Price cap on Russian oil exports: G7 nations agreed in principle to enforce a price cap on Russian oil exports and news this week suggests they are going to go work on the details this week. This may severely restrict Russian oil revenues.

#4 Sanctions and embargos mean Russian supplies (including inputs for armaments such as chips) are facing shortages as well, so time is not on its side. The Western allies see that things are not going well for Russia and are putting maximum pressure on Russia from all fronts. Given that rolling over is not an option, it would not be surprising if Russia tried a different gambit.

#5 From the US perspective, there is no reason to negotiate and Russia knows this: unlike all the Cold War crises, everything is going well and it’s in a position of strength, barely expending much except some armaments in its inventory and a few billion dollars here and there to tie down a (previously) much feared nemesis. From a purely realpolitik perspective (without taking into account humanitarian considerations), the ROI on the current crisis is reaching infinity and in the endgame the US may be able to achieve a level of relative strength against Russia what trillions spent in the Cold War could not achieve. Russia knows this, so there’s unlikely to be any fruitful negotiation in the current status quo.

Faced with the above, from Russia’s perspective, it needs to create a new bargaining chip. Other than nuclear Armageddon (which is decidedly distasteful due to potentially mutually assured destruction implications), the more actionable option would be to vastly reduce oil exports, therefore weaponizing oil in a way similar to natural gas. This might have seemed as outlandish as James Bond movies in the past, but given the Nordstream explosion the past week, anything seems to be fair game as both sides engage in a struggle.

At $90/barrel and roughly 100 million bpd global consumption, roughly $3 trillion of oil is used around the world each year. If Russian exports of crude oil and products, currently at 8 million bpd, are reduced by 25% or 50%, oil could surge a mindboggling amount (it would be difficult to tell how much they would surge by, but the oil crisis of 1973 saw a quadrupling of oil prices):

- This would further cause trillions of dollars of pain to the world economy that is already struggling with high natural gas, coal and electricity prices.

- There would be major ripple effects: for example if oil and gasoline prices double or triple (or gas is unavailable due to rationing), maybe you’ll hold off on a car purchase, thereby devastating new auto sales. This may bring industries (especially in Europe) to a standstill.

- The current crisis is already causing European banks like Credit Suisse and Deutsche Bank to be buckling:

- Credit Suisse has assets of 750 billion CHF and a market cap of $10bn, while JPM has 3.7 trillion USD assets and a market cap of $300 billion. Credit Suisse trading at a fifth per dollar of assets compared to JPM, which shows how little the market is valuing it.

- Similarly, Deutsche Bank has 1.3 trillion EUR in assets and $15bn in market cap, which is even less market cap per dollar of assets compared to JPM.

- 14 years since the Great Financial Crisis of 2008, the much maligned American banks are in a much healthier position than their European counterparts.

- Further stress may precipitate a general European financial crisis (along with the above economic crisis from broad industry shutdowns) and that just might induce Europeans to parley.

- Russia might not even see lower revenues or might even see higher oil revenues as it sells its oil for a higher price even though the volume is lower.

- If you wonder what Russia has to gain from all of this – it might not be able to gain anything concrete from engineering an oil crisis, but if you muddy the water who knows what might happen and besides he’s getting close to the point where he doesn’t have anything to lose anyway, so from his perspective might as well try something. There’s nowhere for the world to get 4 million bpd oil on short notice (much less 6 million or even 8 million) and with so many industries at the brink, Europeans might just give up. Note how the German parliament voted against a symbolic bill to further provide Ukraine with arms.

Roadmap for investors

At this stage, this is still a “low likelihood event” and would still be a black swan. But if such an Russian oil embargo occurred, what should investors do?

If we look at the 1970s, which are often thought of as a bad period for equities, it may be a good reference point.

Observation #1: The 1970s were bad but not that bad for the long term investor.

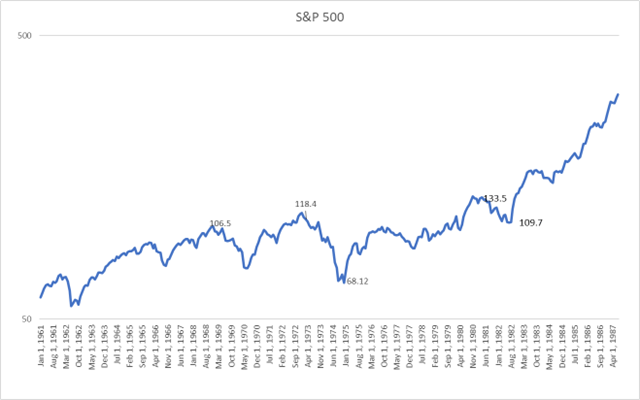

S&P 500 (Public info)

The 1970s were often remembered as a period of stagnation – the economy was in stagflation and there were multiple oil crises and this and that. But for investors with a long term horizon and no leverage, it wasn’t that terrible, all investors had to do was:

- Buy massive dips (ignore the doom and gloom) especially during recessions. The 1973 OPEC oil crisis had no lasting damage on equities. You might even argue it was a great time to load up on lower valued stalwarts. Throughout the 1970s, the S&P 500 never reached the lows of the OPEC oil crisis ever again. The rest of the 1970s were mainly spent, well, going nowhere.

- Stick with stalwarts with solid businesses and fair valuations (i.e. avoid highflying stories like Avon). Probably no one even remembers why Avon justified high valuations in 1973 but Ford is still selling cars and Kellogg is still selling cornflakes. 10 years from now people will still be buying cornflakes and dog food but people might not remember why Tesla was once trading at $750 bn market cap (or buy into whatever reason they’re buying into right now). More single stock examples below.

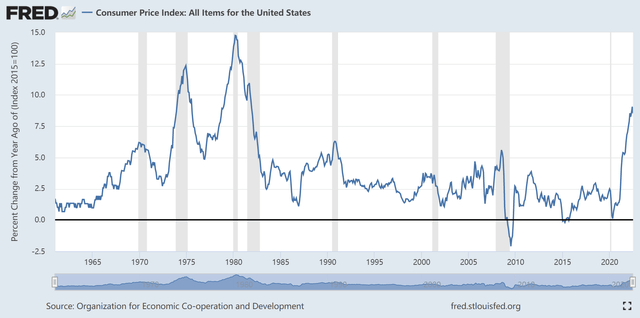

- Avoid getting caught in bull traps – the inflation problem was not “solved” till the 1980s, inflation decreased sharply for multiyear periods twice in the 1970s but both were short lived before another wave of inflation as shown below.

CPI (FRED)

- Lower equity return expectations. The S&P did not reach new highs till about 10 years later. 1973 was considered a peak in the market, with a Shiller PE of almost 20, levels it would not reach for another 2 decades. What appears to have happened during the 1970s is that overall stock indices broadly went nowhere in cyclical motions while earnings grew due to a mix of economic growth and inflation. Valuations became depressed due to higher rates and the “malaise” of inflation. This actually paved the way for the bull market post 1982 – once interest rates were lowered, the horse was out of the barn.

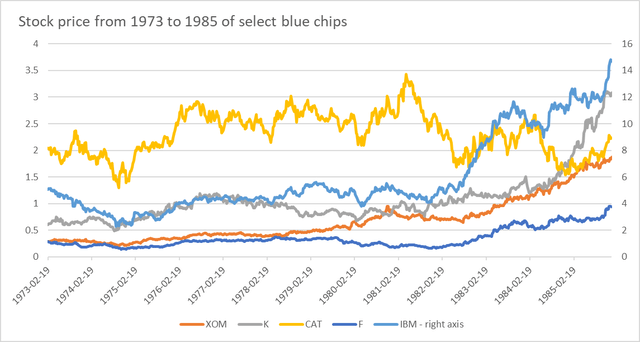

Observation #2: Blue chips didn’t do too badly even if you held from the peak in October 1973

If you were an individual investor that said “I’m not going to bother guessing what OPEC might or might not do, I’ll just buy and hold for the long term”, as long as you held the right equities, they didn’t do too poorly.

Below are stock prices of Exxon, Kellogg, Caterpillar, Ford and IBM from 1973 to 1985.

select blue chip stock prices (Yahoo finance)

Note: IBM is on the right axis, the other equities are on the left axis

Prices are adjusted for splits and dividends.

A simpler comparison of each stock over the years shown below:

XOM did fairly well, holding its value as energy stocks did well throughout the crisis. XOM even did well throughout to 1985 despite lower oil prices. K and IBM did fairly well even comparing 1982 and 1973, as they almost doubled despite a decade of malaise, which isn’t the greatest thing considering a decade of inflation, but still, given the circumstances, no principal loss suffered despite holding from the peak is not too bad.

|

Closing price |

Oct 1 1973 |

Oct 3 1977 |

Oct 4 1982 |

Oct 7 1985 |

|

XOM |

0.32 |

0.41 |

0.76 |

1.77 |

|

K |

0.65 |

1.04 |

1.23 |

2.7 |

|

CAT |

2.35 |

2.56 |

1.71 |

1.98 |

|

F |

0.26 |

0.32 |

0.28 |

0.76 |

|

IBM |

3.8 |

4.24 |

6.91 |

11.86 |

Source: Yahoo finance

Summary:

- It is worth considering that Russia may embargo oil exports in order to improve its bargaining position or if nothing else, create confusion and chaos given its limited options and unenviable position.

- To hedge against this, it may be worth having some exposure blue chip oil stocks (detailed reasons elaborated here), suffice to say that oil stocks are probably a worthwhile investment even without the Russian oil embargo possibility and would provide some upside in case there is such an embargo..

- If an investor does not want to invest in oil stocks, but is then hit with a collapsing stock market if such an eventuality occurs, then using 1973-74 OPEC oil embargo as a reference:

- Buy stalwarts at a reasonable price on a dip. No matter how tough the Fed sounds on inflation and even though inflation will be surging if the Russian oil embargo is announced, life will eventually go on and usually sooner rather than later.

- Ideally reduce exposure to speculative names in advance or when the embargo occurs.

Be the first to comment